Labour market measurement – Part 1

I am now using Friday’s blog space to provide draft versions of the Modern Monetary Theory textbook that I am writing with my colleague and friend Randy Wray. We expect to complete the text by the end of this year. Comments are always welcome. Remember this is a textbook aimed at undergraduate students and so the writing will be different from my usual blog free-for-all. Note also that the text I post is just the work I am doing by way of the first draft so the material posted will not represent the complete text. Further it will change once the two of us have edited it.

Chapter 10 The Labour Market

10.3 Measurement

While up until now we have been concerned with developing an theoretical framework to explain how real GDP and national income is determined, macroeconomics is also concerned with understanding the dynamics of employment and, relatedly, unemployment.

Many a textbook will say that “Macroeconomics is the study of the behaviour of employment, output and inflation”. Further, a central idea in economics whether it be microeconomics or macroeconomics is efficiency – getting the best out of what you have available. The concept is extremely loaded and is the focus of many disputes – some more arcane than others.

At the macroeconomic level, the “efficiency frontier” is normally summarised in terms of full employment, which has long been a central focus of economic theory, notwithstanding the disputes that have emerged about what we mean by the term.

However, most economists would agree that an economy cannot be efficient if it is not using the resources available to it to the limit. In recent decades, the emergence of issues relating to climate change have focused our attention on what that limit actually is. In this Chapter, we focus on the use of labour resources.

The concern about full employment was embodied in the policy frameworks and definitions of major institutions in most nations at the end of the Second World War. The challenge for each nation was how to turn its war-time economy, which had high rates of employment as a result of the prosecution of the war effort, into a peace-time economy, without sacrificing the high rates of labour utilisation.

In this section, we consider issues relating to measurement. How do we know how much employment there is at any point in time? What is unemployment? Is it a measure of wasted labour resources or are there other considerations that should be taken into account?

Labour Force Framework

The Labour Force Framework constitutes a set of definitions and conventions that allow the national statisticians to collect data and produce statistics about the labour market. These statistics include employment, unemployment, economic inactivity, underemployment, which can be combined with other survey data covering, for example, job vacancies, earnings, trade union membership, industrial disputes and productivity to provide a comprehensive picture of the way the labour market is performing.

The Labour Force Framework is a classification system, governed by a set of rules and categories. It forms the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data. The framework is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop the guidelines or norms for implementing the labour force framework and generating the national labour force data.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics publication – Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods – describes the international guidelines that national statistical agencies agree on which define the organising principles that define the Labour Force Framework.

National statistical agencies work within internationally agreed standards when publishing labour statistics.

At the end of the First World War, the ILO was established (1919) to set minimum labour standards. Each year, there is an International Labour Conference that makes decisions that determine what are called the International Labour Conventions and Recommendations.

One section of these conventions, the – Labour Statistics Convention (No. 160) – was adopted at the 71st International Labour Conference in 1985 and modernised the previous convention that was agreed in 1938.

Article 1 of the 1985 Convention requires all member states of the ILO (including Australia and the US) to:

regularly collect, compile and publish basic labour statistics, which shall be progressively expanded in accordance with its resources to cover the following subjects:

(a) economically active population, employment, where relevant unemployment, and where possible visible underemployment;

(b) structure and distribution of the economically active population, for detailed analysis and to serve as benchmark data;

(c) average earnings and hours of work (hours actually worked or hours paid for) and, where appropriate, time rates of wages and normal hours of work;

(d) wage structure and distribution;

(e) labour cost;

(f) consumer price indices;

(g) household expenditure or, where appropriate, family expenditure and, where possible, household income or, where appropriate, family income;

(h) occupational injuries and, as far as possible, occupational diseases; and

(i) industrial disputes.

The ILO also publish very detailed technical guidelines about how these statistics should be collected and disseminated via one of its technical committees – the International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). This Committee meets about every five years and its membership comprises government officials who are “mostly appointed from ministries responsible for labour and national statistical offices” and representatives from employer’s and worker’s organizations.

The ICLS agree on resolutions which then determine the way in which the national statistical offices collect and publish data. While the national statistical agencies have some discretion as to how they undertake the task of preparing labour statistics, in general, there is widespread uniformity across agencies.

Labour statistics are often drawn into political controversies and government critics have been known to accuse the government of manipulating the official data for political purposes. But once you understand the process, which governs the structure of the labour force statistical collection and the definitions outlined in the ICLS resolutions it is hard to make that argument.

This is not to say that there is not a lot of debate about what the official labour statistics measure and whether they can be improved but it is important to understand how they are collected.

The rules contained within the labour force framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework.

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework.

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at a specified moment in time.

The system of priority rules are applied such that labour force activities take precedence over non-labour force activities and working or having a job (employment) takes precedence over looking for work (unemployment). Also, as with most statistical measurements of activity, employment in the informal sectors, or black-market economy, is outside the scope of activity measures.

There is a long-standing concept of “gainful work”, which shape these priorities but have proven controversial. Gainful work is typically seen as work for profit that receives payment. So a person who does ironing for a commerical laundry would be considered to be pursuing gainful work whereas if the same person was ironing for their familty they would be considered inactive.

Clearly, with economic and non-economic roles being biased along gender lines, this distinction leads to an undervaluation of a substantial portion of work performed by females.

Thus paid activities take precedence over unpaid activities such that for example ‘persons who were keeping house’ as used in Australia, on an unpaid basis are classified as not in the labour force while those who receive pay for this activity are in the labour force as employed. Similarly persons who undertake unpaid voluntary work are not in the labour force, even though their activities may be similar to those undertaken by the employed.

The category of ‘permanently unable to work’ as used in Australia also means a classification as not in the labour force even though there is evidence to suggest that increasing ‘disability’ rates in some countries merely reflect an attempt to disguise the unemployment problem.

In terms of those out of the labour force, but marginally attached to it, the ILO states that persons marginally attached to the labour force are those not economically active under the standard definitions of employment and unemployment, but who, following a change in one of the standard definitions of employment or unemployment, would be reclassified as economically active.

Thus for example, changes in criteria used to define availability for work (whether defined as this week, next week, in the next 4 weeks etc.) will change the numbers of people classified to each group. This also provides a great potential for volatility in series and thus there can be endless argument about the limits applied to define the core series.

Figure 10.1 summarises the Labour Force Framework as it is applied in Australia but this is a common organising structure across all nations.

Figure 10.1 The Labour Force Framework

National statistical agencies conduct a Labour Force Survey (LFS) on a regular basis, usually monthly, which collects data using the concepts and definitions provided for in the Labour Force Framework.

The Working Age Population is typically all citizens above 15 years of age. In several countries, the age threshold is 16 years of age. In the past, the age span was 15 years to retirement age, usually around 65 years of age. However, as social changes have seen age discrimination laws come into force in many nations, the upper age limit has been accordingly abandoned in several nations.

The Working Age Population is then decomposed into the Labour Force (the “active” component) and Not in the Labour Force (the “inactive” component). A worker is considered to be active if they are employed or unemployed.

The proportion of workers who comprise the labour force is governed by the Labour Force Participation Rate, which is defined as:

… the ratio of the labour force to the working age population, expressed in percentages.

We will consider the cyclical behaviour of the participation rate later in the Chapter.

The ILO defines a person as being employed if:

… during a specified brief period such as one week or one day, (a) performed some work for wage or salary in cash or in kind, (b) had a formal attachment to their job but were temporarily not at work during the reference period, (c) performed some work for profit or family gain in cash or in kind, (d) were with an enterprise such as a business, farm or service but who were temporarily not at work during the reference period for any specific reason. (Current International Recommendations on Labour Statistics, 1988 Edition, ILO, Geneva, page 47).

What constitutes “some work” is controversial. In Australia, for example, a person who workers one or more hours a week for pay is considered to be employed. So the demarcation line between employed and unemployed is, in fact, very thin.

Within the employment category further sub-categories exist, which we will consider later. Most importantly, significant numbers of employed workers might be classified as being underemployed if they are not able to work as many hours as they desire because there is insufficient aggregate demand in the economy at that point in time.

What constitutes unemployment? According to ILO concepts, a person is unemployed if they are over a particular age, they do not have work, but they are currently available for work and are actively seeking work. Unemployed people are generally defined to be those who have no work at all.

Unemployment is therefore defined as the difference between the economically active population (labour force) and employment.

Two derivative measures capture a lot of public attention. First, the Unemployment Rate is defined as:

… the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the civilian labour force.

The US unemployment rate in October 2012 was 7.9 per cent. This was derived from a labour force estimate of 155,641 thousand and total estimated unemployment of 12,258 thousand.

Second, statisticians publish the Employment-Population ratio, which is:

… the proportion of an economy’s working-age population that is employed.

Note that the denominator of these two ratios is different. The unemployment rate uses the labour force while the employment-population ratio uses the working age population.

We will see why this difference matters later when we consider the way the labour market adjusts over the economic cycle and how this impacts on our interpretation of the state of the economy as summarised by the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Conclusion

I will be continuing this Chapter next week. Once the measurement section is finished the Chapter will turn to a theoretical discussion concerning the determination of employment and unemployment and the debates about real wages etc.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back again tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

★

MMTの懐疑的入門(8)蝶番としての雇用保障制度

今回は、MMTの理論家たちが主張しているJG(ジョブ・ギャランティ)制度について、もう少し詳しく述べておくことにしよう。前回、すでに簡単に触れたように、このJGはインフレを抑制できることになっている。

MMTの考え方で財政と金融を管理していったとき、制約となるのはインフレと資源であることはすでに述べたが、完全雇用を達成するために統合政府の支出をコントロールしていくことが目的のひとつであるMMTにとって、インフレが鬼門となる。したがって、このJGこそがMMTの「肝」というべきものなのである。

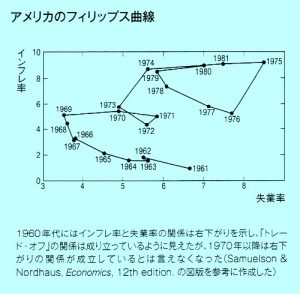

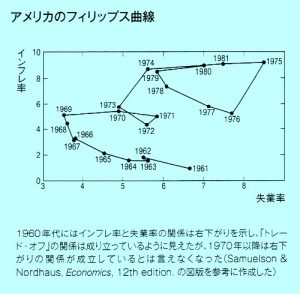

その前に、雇用とインフレとの関係について、これまで経済学がどのように捉えてきたか、簡単に復習しておく必要がある。戦前はおくとして、戦後、アメリカを中心に普及をみた米版ケインズ経済学においては、フィリップス曲線が採用された。

この曲線は英国の経済学者であるA・W・フィリップスが1958年に発表したもので、横軸に失業率をとり、縦軸にインフレ率をとると、右下がりの曲線が描かれることになる。つまり、失業率を下げようとして経済を刺激して加速するとインフレ率が上がり、インフレ率を下げようとすると失業率が上がるのである。 そこで、1960年代に米経済学界を代表するポール・サミュエルソンは雇用とインフレとの間には「トレード・オフ」の関係があり、それは政権の選択の問題だと述べた。これは本来、非自発的失業をなくすとしていたケインジアンからすると裏切りのように思えたので、ある日本のケインジアンなどは「サミュエルソンは議論のハイジャックをしてしまった」と嘆いた。つまり、フィリップス曲線を使っていらぬ妥協をしたというわけである。

そこで、1960年代に米経済学界を代表するポール・サミュエルソンは雇用とインフレとの間には「トレード・オフ」の関係があり、それは政権の選択の問題だと述べた。これは本来、非自発的失業をなくすとしていたケインジアンからすると裏切りのように思えたので、ある日本のケインジアンなどは「サミュエルソンは議論のハイジャックをしてしまった」と嘆いた。つまり、フィリップス曲線を使っていらぬ妥協をしたというわけである。

しかし、仲間内で論争をしているうちはよかったが、60年代後半にはミルトン・フリードマンがこの「トレード・オフ」であるという主張自体に疑問を呈し始めた。70年代になるとフィリップス曲線がサミュエルソンたちの予想を裏切って回転するようになり、まったく「トレード・オフ」を示さなくなったので、フリードマンは自信をもって「自然失業率」があると主張するようになった。

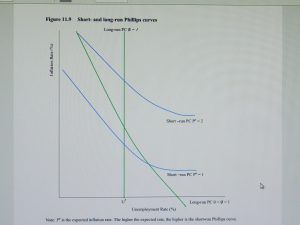

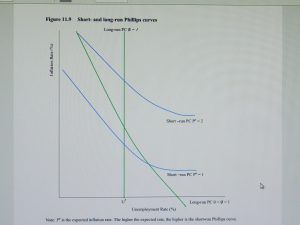

この自然失業率というのは、経済の仕組みや構造から生まれるものであって、それ以下にまで下げようと経済を加速するとインフレが起るというわけである。その後、ニュー・ケインジアンたちが、インフレを引き起こさない失業率(NAIRU)という概念を提示して、短期的にはトレード・オフが成立するが、長期的には経済を加速させるとNAIRUに突き当ると論じるようになった。このNAIRUによるフィリップス曲線は垂直であり、ポール・クルーグマンは教科書のなかで、NAIRUと自然失業率は同じものだと認めている。

このように、ニュー・ケインジアンたちも、短期では失業率とインフレ率はトレード・オフの関係があり、長期では自然失業率に突き当るという、いわゆる「古典派の二分法」を認めるようになっていたわけだが、MMTはこうした考え方にも真っ向から反旗を翻した。

MMT理論家によれば、まず、短期と長期による二分法を拒否して、その中間的なフィリップス曲線が成り立つという。また、このフィリップス曲線をなく(エリミネイト)することができると主張するようになった。今回、注目しておきたいのは後者のほうで、いったいいかなる方法でフィリップス曲線を抹殺するのだろうか。

ここらへんは、ビル・ミッチェルがMMTの論文集『政府支出』(右の図版:作成がまだなので、とりあえず写真で表示:3種類のフィリップス曲線)に書いているので、それを見ていくことにしよう。彼らが提示しているのが、いうまでもなくJG(ジョブ・ギャランティ)制度である。これも細かいことを言い出すと長くなるので、かなりはしょることになるが、ともかく、MMT理論家たちは雇用と失業を細かくわけ(下の写真:同じく『政府支出』より)、ケインズの『一般理論』で論じられたたような非自発的失業者を抹殺すべく構想している。

ここらへんは、ビル・ミッチェルがMMTの論文集『政府支出』(右の図版:作成がまだなので、とりあえず写真で表示:3種類のフィリップス曲線)に書いているので、それを見ていくことにしよう。彼らが提示しているのが、いうまでもなくJG(ジョブ・ギャランティ)制度である。これも細かいことを言い出すと長くなるので、かなりはしょることになるが、ともかく、MMT理論家たちは雇用と失業を細かくわけ(下の写真:同じく『政府支出』より)、ケインズの『一般理論』で論じられたたような非自発的失業者を抹殺すべく構想している。

まず、非自発的失業者は政府がつくった「雇用者プール」(JGE:ジョブ・ギャランティ・エンプロイメント)のなかに入ることになる。JGEの人たちは最低賃金を保障されて政府から仕事をもらうことができる。この雇用プールには、たとえば技術力があっても満足できない職しかないような失業者も当面属すことができる。

次に、政府が注意を払うのはBER(バッファ・エンプロイメント・レシオ:緩衝雇用率)の数値である。BER=JGE/E(JGE=プール雇用者数、E=総雇用者数)で示される数値は、経済が加速すれば下降し減速すれば上昇する。この数値を観察するとともに、民間の雇用動向にも気配りするのが政府の仕事となるわけである。

そこで、民間部門に賃金上昇への圧力が生まれたと思われたときには、金融および財政でのてこ入れ政策を少しばかり抑制する。その抑制の結果として、民間部門の労働力がJGEにトランス(移動)されるというのだが、要するに、緊縮された結果として雇用を失った労働者が、政府の雇用者プールに入って来るというわけである。ミッチェルは述べている。

「定義上、失業者は労働市場価格をもっていない。というのは、彼らの労働への需要が存在しないからである」 それはそうだろう、失業者(正確には非自発的失業者)はすべて雇用者プールのなかに繰り入れられているわけで、そもそも失業者は存在しないことになるわけだから。

それはそうだろう、失業者(正確には非自発的失業者)はすべて雇用者プールのなかに繰り入れられているわけで、そもそも失業者は存在しないことになるわけだから。

しかし、これが本当に実現するかといえば、多くの障害が予想されるだろう。まず、財界はこうした失業者ゼロの状態を喜ばないだろうし、たとえば、人材産業は自分たちの仕事をかなり取られてしまう。さらに、組織率が著しく低くなったアメリカの労働者が、こうした制度を望むかどうかすら不明なのだ。結局、かなりの独裁的政府が必要になる。

とはいえ、このJGがMMTの主張する新しい財政・金融制度にとって、きわめて重要であり、さらにいえば、この制度がなければ彼らのいう財政・金融制度が成り立たないといってもよい。JGはMMTの蝶番のような機能を果たしており、わたくしが「MMTは欧米の高い失業率を背景に注目されるようになった」と述べていることも、けっして誇張ではなく、充分に納得いただけるのではないかと思う。

この制度が成り立つか否かは、もう一度、回を改めて細かく検討することにして、気になるのは日本のMMT派の主張である。彼らはさすがに失業率2.4%の下で、「フィリップス曲線をなくしてみせます」ということは避けている。しかし、それでは彼らの「蝶番」になるのは何なのだろうか。

先走っていえば、完全雇用はMMT理論家たちが思うほど安定した蝶番とは成りえないと思うが、その上限は急速な移民政策でも再開しなければ間違いなく存在しており、それがインフレを抑制すると考えることは論理的にはそこそこ可能だ。しかし、たとえばこの完全雇用の代わりに「災害対策」とか「日本の防衛」を据えたとき、果たして蝶番の機能を果たすだろうか。わたくしには、かなり疑問に思われるのである。

★

MMTの思想的背景:歴史学と文化人類学

日本では最近になって注目されるようになったMMT(現代貨幣理論)だが、欧米ではそれなりに思想的な背景があって形成されたものであることは間違いがない。政治的な背景についてはすでに書いたので、ここでは経済学以外の分野での動向をみておくことにしよう。

MMTに特徴的な主張にはいくつかあるが、ことに際立っているのが貨幣を「負債」として見ることを強調することであり、しかも、論理的に密接な、「貨幣国定説」を採用している点だろう。つまり、貨幣とは政府による国民からの「借金」として位置づけられ、それゆえに、政府には独占的なコントロールの権限が与えられるとともに、国民への「返済」が科されている(つまり、政策によって国民の福祉を増大する)という考え方をするわけである。

日本のMMT派の論者も、MMTの貨幣国定説は正しい説で、それは歴史学や文化人類学によっても証明されていると、さかんに主張しているようである。つまり、自分たちが拠って立つ新しい経済学は、歴史学や文化人類学も支持しているから正しいのであって、MMT派が主張することは、ゆえに間違っていないということになるらしい。

これまでも、さまざまな論争において自分たちが正しいと主張することは珍しくないが(そもそも、そう思わなければ論争するわけもないが)、しかし、あまり露骨に「正しい」「証明されている」といわれると、ちょっと眉に唾をしたくなる。そこで、ためしにMMTの入門書とされているL・R・レイの『現代貨幣理論 第2版』の該当箇所をめくってみると、ざっと3人ほどの名前と言葉が引用されて根拠とされている。

「われらの罪に満ちた負債」と述べたマーガレット・アトウッド、「ギリシャの貨幣は都市国家の権威を示す印がついていた」と語るレズリー・カーク、それに「国定貨幣は少なくとも4000年前まで遡れる」と言ったケインズである。しかし、アトウッドは作家で詩人であって、カークはギリシャ古典学者である。もちろん、詩人でも適切な表現をしているということだろうし、ギリシャ古典学者でも貨幣製造と古代文化に詳しい人だから登場するのだろうが、負債問題を論じるのに経済学者がひとりというのは、ちょっと迫力に欠けるような気がしないでもない。

これはおそらく「入門書」ということで、著者のレイが、あんまりお堅い学者ばかり並べるのは遠慮したためかもしれないが、もうひとつ、MMTの根拠を固めるためには、積極的に他分野の見解を取り入れるという姿勢の表れだろう。レイの周辺で活躍している歴史学者とか文化人類学者といえば、『マネー:その負債と権力の5000年史』を書いたレギュラシオン派のミッシェル・アグリエッタや、世界的ベストセラーの『負債論』で知られるデビッド・グレーバーをおとすわけにはいかない。さらに、グレーバーとの関係でいえば『経済人類学』のキース・ハートや中近東に詳しい経済史家のマイケル・ハドソンなども考慮すべきだろう。

レイが切り開いたとされるMMTの貨幣論では、主にG・F・クナップが登場して、彼の『貨幣国定説』(1905)が解説される。簡単にいえば、通貨というものは国家の権威を背景として流通が可能になるのであって、アダム・スミスが採用した「物々交換から特定の貴金属が通貨として採用されるにいたった」という商品通貨論もしくは貴金属通貨論は激しい攻撃の対象となっている。さらに、1913年に「貨幣は計算手段である」と主張したミッチェル・イネスの論文「通貨とは何か?」が再評価されて、レイたちは当時は異端とされたイネスの論文集を組んでいるほどなのだ。

こうした通貨国定学説(通貨の本質を権威のお墨付きに求めることから「表券主義」ともいわれる)に基づくMMTは、とくに、オーストリア学派のルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼスが唱えたメタリズム(金属主義)に対して繰り返し批判している。フォン・ミーゼスは政府の非介入を唱え、『貨幣および流通手段の理論』(1912)のなかで、貨幣は金の素材としての交換価値が受け継がれたと論じた。レイたちMMTにとっては、天敵というべき存在なのだろう。

MMT理論家たちは貨幣の起源についても繰り返し論じているが、メソポタミア文明における粘土板に、徴収すべき税の数値が刻まれていたことを根拠に、すでにこの時代には「貨幣」があったのだとする。この説は、ケインズが『貨幣論』(1930)の冒頭で展開した貨幣分類論のなかでも採用しているから、MMTの理論家たちは彼らの始祖のひとりであるケインズの説を継承していることになる。

もちろん、MMT派はそのままケインズを素朴に引き継いだわけではなく、ケインズも参照したクナップ、イネスに加えて、さきほど触れたマイケル・ハドソンたちのメソポタミア貨幣起源説によって自説を強化している。さらには、レイの現代貨幣理論に刺激をうけたグレーバーやアグリエッタたちの研究を取り込み、歴史学や経済人類学でも貨幣国定説は支持されているとして自信を深めているわけだ。

興味深いのは、アグリエッタを中心とするフランス研究者たちのグループに「原初的負債論」が誕生したことだろう。これは、貨幣の起源を研究するいっぽうで、古代の宗教感覚を探究していくなかで生まれたもので、人間の誕生じたいが負債すなわち罪であり(たとえば古代インドの教典では負債は罪業の意味をもっているという)、ここからレイのように経済の負債と聖書の原罪とを接続して、政府の負債すなわち貨幣であると敷衍する者もいる。つまり、負債をかかえた政府は、完全雇用を達成してこそ任務を果たしたことになるという論理を展開するのである。

こうした周辺学問から多くの要素を吸収している様子は、現代の経済学流派としてはかなり珍しいと思われる。しかも、政治学や社会学というのなら普通だが、歴史学、文化人類学、はては宗教学との融合をはかろうというのは、なかなか見上げたものだといってよいかもしれない。

とはいえ、こうした越境的な議論が、ほんとうに稔りの多いものなのかは、やはり留保が必要ではないかと思う。たとえば、アグリエッタたちの「原初的負債論」について、興味深い話だとは思っても、たとえばグレーバーなどは、これが貨幣論に結びつくかについては、やや及び腰である。「この種の絶対的生の負債がどのようにして貨幣へと換算可能になるのか、はっきり説明されていない」。ましてや、東アジア文化圏の「租庸調」をいかに検討したところで、そこに原罪を発見するのは困難である。

さきほど述べたメソポタミアの粘土板に記録された税収の予定量についても、これがすぐに「貨幣」といえるかは、やはり疑問なしとはしない。ケインズはこうした計算貨幣money of accountこそが本源的概念だというのだが、では、同地域の同時期に粘土板とは別に秤で量った貴金属が実質的に貨幣であったこととどう調和するのだろうか。しかも、表券主義が主張するように、前7世紀に作られたリディアの金貨には前もって計量した金に王家の紋章がついていて、それゆえにこそ貨幣の本質は国定で表券なのだという議論とは矛盾しないのだろうか。

いまの先進国を見るかぎり、たしかに表券主義の時代となったことは明らかだが、それはごく最近の話で、それまではさまざまな形態の「貨幣」が並行して存続していたし、これからも何種類もの「貨幣」が存続する可能性がある。(もちろん、こういったからといって、単なる投機だけが目的のクリプト・カレンシーを未来の貨幣などと呼ぶ気はない)。だからこそ、ケインズは『貨幣論』のなかで、ここに掲げた図版のようなものを添付して、ますます議論を複雑にしているのである。

若いころに文化人類学の雑誌の編集をやったこともあって、経済学に興味をもたざるを得なくなってからでも、やはり文化人類学と経済学の越境的な考察が好きだった。そのなかでも、カール・ポランニーの『大転換』を中心になって翻訳した吉沢英成氏の著作『貨幣と象徴』にある種の偏愛をもってきた。もちろん、1981年初版のこの本は当時の言語学と記号論の隆盛という時代背景をもっているのだが、制度論、素材論、精神分析論、記号学、言語学などが縦横に導入されていて、包括性と柔軟性は依然として超えるものがない。

こうした著作を読んでおけば、なにかひとつの起源からすべてを引き出すという起源論は、いかめしい相貌をもっていても、われわれをみじめな袋小路へと導くだけだと気づくのではないだろうか。そもそも、文化人類学にせよ経済人類学にせよ、わたくしの見るところ、何かに固執する発想から解放させてくれるのに有効でも、具体的な目標や政策を決めるのにはまるで向かない。それは経済人類学の祖であるポランニー自らが語っていたのである。

「原初的社会の研究はしばしばその社会を理想化しがちであるが、研究者はそういうことのないように気をつけねばならない」

●MMTについては「コモドンの空飛ぶ書斎」で「MMTの懐疑的入門」を連載中

ケインズ『貨幣論』の貨幣分類

債務の承認→銀行貨幣 → 銀行貨幣

/ \ /法定不換貨幣

計算貨幣 代表貨幣

\ / \

本来の貨幣→国家貨幣 管理貨幣

\ /

商品貨幣

\商品貨幣

土器に印をつける方が金属鋳造より楽なのは理解出来る

(ケインズが調べた時の)インドで起きたことをみれば

あるいはアメリカの事例からみれば(金を流失させないための兌換停止だから)

商品としての金は無くなるわけではない

あくまで貨幣とは何かという話だ

金を持っていた方が国力は高いが

MMTで供給能力を高めたほうが簡単に国力は上がる

現在財政均衡の美名のもとで貧者から富者への所得移転が強制されている

インフレにならない限り財政出動すべきだというのがMMT (強弱はあるが日米同じ)

ただしBIはインフレになる

失業者が失業者のままだから

問題はインフレいうよりインフレの不安定性だ

MMTはこのことをどの学派より考えている

貯蓄に回されない財政政策が自殺者の増加を止める

そこで、1960年代に米経済学界を代表するポール・サミュエルソンは雇用とインフレとの間には「トレード・オフ」の関係があり、それは政権の選択の問題だと述べた。これは本来、非自発的失業をなくすとしていたケインジアンからすると裏切りのように思えたので、ある日本のケインジアンなどは「サミュエルソンは議論のハイジャックをしてしまった」と嘆いた。つまり、フィリップス曲線を使っていらぬ妥協をしたというわけである。

そこで、1960年代に米経済学界を代表するポール・サミュエルソンは雇用とインフレとの間には「トレード・オフ」の関係があり、それは政権の選択の問題だと述べた。これは本来、非自発的失業をなくすとしていたケインジアンからすると裏切りのように思えたので、ある日本のケインジアンなどは「サミュエルソンは議論のハイジャックをしてしまった」と嘆いた。つまり、フィリップス曲線を使っていらぬ妥協をしたというわけである。 ここらへんは、ビル・ミッチェルがMMTの論文集『政府支出』(右の図版:作成がまだなので、とりあえず写真で表示:3種類のフィリップス曲線)に書いているので、それを見ていくことにしよう。彼らが提示しているのが、いうまでもなくJG(ジョブ・ギャランティ)制度である。これも細かいことを言い出すと長くなるので、かなりはしょることになるが、ともかく、MMT理論家たちは雇用と失業を細かくわけ(下の写真:同じく『政府支出』より)、ケインズの『一般理論』で論じられたたような非自発的失業者を抹殺すべく構想している。

ここらへんは、ビル・ミッチェルがMMTの論文集『政府支出』(右の図版:作成がまだなので、とりあえず写真で表示:3種類のフィリップス曲線)に書いているので、それを見ていくことにしよう。彼らが提示しているのが、いうまでもなくJG(ジョブ・ギャランティ)制度である。これも細かいことを言い出すと長くなるので、かなりはしょることになるが、ともかく、MMT理論家たちは雇用と失業を細かくわけ(下の写真:同じく『政府支出』より)、ケインズの『一般理論』で論じられたたような非自発的失業者を抹殺すべく構想している。 それはそうだろう、失業者(正確には非自発的失業者)はすべて雇用者プールのなかに繰り入れられているわけで、そもそも失業者は存在しないことになるわけだから。

それはそうだろう、失業者(正確には非自発的失業者)はすべて雇用者プールのなかに繰り入れられているわけで、そもそも失業者は存在しないことになるわけだから。

0 件のコメント:

コメントを投稿