Does Consciousness Exist? (Essays in Radical Empiricism)

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2017/10/1does-consciousness-exist-essays-in.html@

レベッカ・ソルニット『災害ユートピア』とウィリアム・ジェイムズ

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2011/05/blog-post.html?m=0

NAMs出版プロジェクト: 1755年のリスボンの大震災に関して(ヴォルテールとルソー)

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2011/04/blog-post_5916.html

経験論は明治期に多大な影響を持った。しがらみのない経験論は独立したアメリカで生まれ維新の明治人が共鳴した(無神論が背景にある)。ただしその影響下で西田と漱石は対象的な二面性を示す。西田は自他を華厳的につなぎ、漱石は自他の断絶を観察した。

西田はライプニッツからヘーゲルに飛び。漱石はカント的アンチノミーに止まった。ジェイムズが否定したカント(さらにジェイムズの批判したフロイトの超越的な部分)の系譜に漱石は結果的に連なる。漱石の方が禅を継承している。

ベルグソンとの関連も興味深い。

純粋経験の哲学:

http://mahlersociety.cocolog-nifty.com/dokusyo/2008/11/post-4ff0.html

カントは、わたしのすべての対象には「わたしは思考する」が伴いうるのでなければならない、といったが、この「わたしは思考する」とは、まさしくすべての対象に実際に伴っている「わたしは呼吸する」のことである。』(第一章 「意識」は存在するか より44ページ)

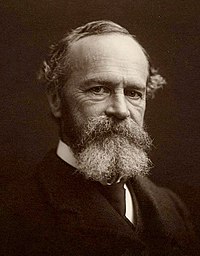

ウィリアム・ジェイムズ(1842-1910)の「純粋経験の哲学」(伊藤邦武編訳、岩波文庫)

別訳 根本的経験論 白水社

Does Consciousness Exist? (1904). By William James in ESSAYS IN RADICAL EMPIRICISM (1904,1912) // Fair Use Repository

http://fair-use.org/william-james/essays-in-radical-empiricism/does-consciousness-exist

VIII

…The I think

which Kant said must be able to accompany all my objects, is the I breathe

which actually does accompany them. There are other internal facts besides breathing (intracephalic muscular adjustments, etc., of which I have said a word in my larger Psychology), and these increase the assets of consciousness,

so far as the latter is subject to immediate perception; but breath, which was ever the original of spirit,

breath moving outwards, between the glottis and the nostrils, is, I am persuaded, the essence out of which philosophers have constructed the entity known to them as consciousness. That entity is fictitious, while thoughts in the concrete are fully real. But thoughts in the concrete are made of the same stuff as things are.

「意識は存在するか」1904

1912年まとめられて刊行

漱石と柄谷行人 - Don't Let Me Down

http://blog.goo.ne.jp/wamgun/e/172a27f28d32b4c14a385943a14bb569(柄谷行人「意識と自然」平凡社ライブラリー版『増補 漱石論集成』(2001))の最初のほうに夏目漱石の「断片」(明治38-39年)(1905-6)引用がある;

★ 2個の者がsame spaceヲoccupyスル訳には行かぬ。甲が乙を追い払うか、乙が甲をはき除ける2法あるのみぢや。甲でも乙でも構はぬ強い方が勝つのぢや。理も非も入らぬ。えらい方が勝つのぢや。上品も下品も入らぬ図々敷方が勝つのぢや。賢も不肖も入らぬ。人を馬鹿にする方が勝つのぢや。礼も無礼も入らぬ。鉄面皮なのが勝つのじや。人情も冷酷もない動かぬのが勝つのぢや。文明の道具は皆己を節する器械ぢや。自らを抑える道具ぢや、我を縮める工夫ぢや。人を傷つけぬ為め自己の体に油を塗りつける[の]ぢや。凡て消極的ぢや。此文明的な消極な道によつては人に勝てる訳はない。― 夫だから善人は必ず負ける。君子は必ず負ける。醜を忌み悪を避ける者は必ず負ける。礼儀作法、人倫五常を重んずるものは必ず負ける。勝つと勝たぬとは善悪の問題ではない ―powerデある ―willである。

Does Consciousness Exist? (1904). By William James in ESSAYS IN RADICAL EMPIRICISM (1904) // Fair Use Repository

http://fair-use.org/william-james/essays-in-radical-empiricism/does-consciousness-existRepresentativetheories of perception avoid the logical paradox, but on the other hand they violate the reader's sense of life, which knows no intervening mental image but seems to see the room and the book immediately just as they physically exist.

VI

The next objection is more formidable, in fact it sounds quite crushing when one hears it first.

If it be the self-same piece of pure experience, taken twice over, that serves now as thought and now as thing

— so the objection runs — how comes it that its attributes should differ so fundamentally in the two takings. As thing, the experience is extended; as thought, it occupies no space or place. As thing, it is red, hard, heavy; but who ever heard of a red, hard or heavy thought? Yet even now you said that an experience is made of just what appears, and what appears is just such adjectives. How can the one experience in its thing-function be made of them, consist of them, carry them as its own attributes, while in its thought-function it disowns them and attributes them elsewhere. There is a self-contradiction here from which the radical dualism of thought and thing is the only truth that can save us. Only if the thought is one kind of being can the adjectives exist in it

intentionally

(to use the scholastic term); only if the thing is another kind, can they exist in it constituitively and energetically. No simple subject can take the same adjectives and at one time be qualified by it, and at another time be merely of

it, as of something only meant or known.

VI

次の異議申し立てはもっと恐るべきものです。実際、最初に聞いたときにはかなり粉砕されているようです。

もしそれが純粋な体験の自己同一作品であれば、今度は思考として、現時点では物事として

- 異議が執行されます

- その属性は基本的に2つの取り組みにおいて異なるはずです。

ものとして、経験は延長されます。

思ったように、それはスペースや場所を占有しません。

物として 、それは赤く、堅く、重いです。 赤、堅いまたは重い考えを聞いたことがある人はいますか? しかし、今でも、あなたは、出現するものだけが経験され、そのような形容詞だけが現れると言っています。 どのようにして、その事物 - 機能における1つの経験は、それらから成り立ち、それらから成り立ち、それ自身の属性としてそれらを運ぶことができ、思考機能においては、それを否定し、それらを他の所に帰属させる。 思考や事の根本的な二元性が私たちを救う唯一の真実である自己矛盾がここにあります。思考がある種のものである場合にのみ、形容詞が意図的に

(学問用語を使用するために)存在することができます。 物事が別の種類である場合にのみ、構成的かつ精力的に存在することができます。 単純な主語は同じ形容詞をとることはできませんし、同時にそれによって修飾されることはできません。

根本的経験論 (イデー選書) 単行本 – 1998/5/1

| 根本的経験論 | |

| 叢書名 | イデー選書 ≪再検索≫ |

| 著者名等 | ジェイムズ/〔著〕 ≪再検索≫ |

| 著者名等 | 桝田啓三郎/訳 ≪再検索≫ |

| 著者名等 | 加藤茂/訳 ≪再検索≫ |

| 出版者 | 白水社 |

| 出版年 | 1998.05 |

| 大きさ等 | 20cm 277p |

| 注記 | Essays in radical empiricism. |

| NDC分類 | 133.9 |

| 目次 | 1 「意識」は存在するか;2 純粋経験の世界;3 事物とその諸関係;4 いかにし て二つの心が一つの事物を知りうるか;5 純粋経験の世界における感情的事実の占める 位置;6 活動の経験;7 人本主義の本質;8 意識の概念;9 根本的経験論は独我 論的か;10 「根本的経験論」に対するピットキン氏の論駁;11 人本主義と真理― 再論;12 絶対論と経験論 |

| ISBN等 | 4-560-02405-7 |

| 書誌番号 | 3-0198030037 |

| 所蔵情報 ( 資料情報 | 予約情報 ) |

https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/4003364066

純粋経験の哲学 (岩波文庫) 文庫 – 2004/7/16

評価(評価: 4.3)評価:4.3-3件のレビュー

ウィリアム ジェイムズ, 伊藤 邦武作品ほか、お急ぎ便対象商品は当日お届けも可能。 ... が、むしろ、誰よりも「現代」に近い感じがする。radical empirisim = pure experienceや 持続の観念(意識の流れ)など、「二元論」に陥らない発想は、少なくとも今日の普通 ...

ジェイムズ哲学の統一的理解への試論 - 中央大学

(Adobe PDF)

中央大学大学院文学研究科哲学専攻博士課程後期課程. 大厩 諒 ..... 本論文の主な 目的は、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ(1842-1910)の哲学的思索(とりわけ意識論と純. 粋 経験論)が、同一の哲学的方法論 .... える人間主義と、そのような支配者としての個人 ではなく、高次の霊的実在に吸収されることを. 希求する神秘主義 ... 文の視点に近い ものだが、二つのレベルを方法論的に正当化する議論が十分になされていると. は言え ない。

Title 夏目漱石とウィリアム・ジェイムズ : 「文芸の哲学的基 礎」を中心に ...

(Adobe PDF)

Title 夏目漱石とウィリアム・ジェイムズ : 「文芸の哲学的基 礎」を中心に ...

(Adobe PDF)

夏目漱石とウィリアム・ジェイムズ : 「文芸の哲学的基. 礎」を中心に .... このように、連続 する意識現象を基礎にして「私」の存在を副次的・派生的な構成物と. した以上、同様 ... 問題となるのは、ただ生きるのではなく、どのような生を選択するか、生きる意味を何に.

夏目漱石とプラグ…

佐藤論考

http://harp.lib.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/hiroshima-cu/file/12219/20151217154724/HJIS20-45.pdf

漱石の「思ひ出すことなど」ではジェイムズのスピリチュアリズムが批判される。

W. ジェイムズ - ホワイトヘッド哲学 - 哲学舎

William James ウィリアムジェイムズ. [伝記] アメリカ出身の生理学・心理学者、哲学者 。 1842年1月11日、ニューヨーク市に生まれる。 ... プラグマティズム』では、真理とは イメージと実在の一致ではなく、ある観念や概念から実際に引き出される個別の結果( ジェイムズはこれを〈額面価格〉と呼ぶ)で ... 科学と近代世界』でホワイトヘッドは、『根本 的経験論』の巻頭論文「意識は存在するか」について、デカルトの『方法序説』と並び称し て ...

2ページ目

純粋経験論が目指したもの―西田幾多郎とジェイムズ、円了 - 東洋大学

(Adobe PDF)

研究』であった。とはいえ、周知のように純粋経験 Pure Experience という主題その. ものは、ヨーロッパの長い哲学的伝統に対してオルタナティヴな思想を生み出そう. として いた同時期のアメリカの哲学者、ウィリアム・ジェイムズによって産みださ. れたものだ。

純粋経験の哲学 | ウィリアム・ジェームズの小説 - TSUTAYA/ツタヤ

プラグマティズムで知られるアメリカの思想家ウィリアム・ジェイムズ(1842‐1910)は 、心理学、宗教学、哲学の各領域で多大な影響力をもった。ジェイムズが晩年に追求 した彼なりの体系的な形而上学“純粋経験の哲学”の構築を、よりシャープなかたちで ...

The Principles of Psychology

William James (1890)

CHAPTER XV.[1]

THE PERCEPTION OF TIME.

Classics in the History of Psychology -- James (1890) Chapter 15

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/prin15.htmThe same space of time seems shorter as we grow older -- that is, the days, the months, and the years do so; whether the hours do so is doubtful, and the minutes and seconds to all appearance remain about the same.

"Whoever counts many lustra in his memory need only question himself to find that the last of these, the past five years, have sped much more quickly than the preceding periods of equal amount. Let any one remember his last eight or ten school years: it is the space of a century. Compare with them the last eight or ten years of life: it is the space of an hour."

So writes Prof. Paul Janet,[36] and gives a solution which can hardly be said to diminish the mystery. There is a law, he says, by which the apparent length of an interval at a given epoch of a man's life is proportional to the total length of the life itself. A child of 10 feels a year as 1/10 of his whole life -- a man of 50 as 1/50, the whole life meanwhile apparently preserving a constant length. This formula roughly expresses the phenomena, it is true, but cannot possibly be an elementary psychic law; and it is certain that, in great part at least, the foreshortening of the years as we grow older is due to the monotony of memory's content, and the consequent simplification of the backward-glancing view. In youth we may have an absolutely new experience, subjective or objective, every hour of the day. Apprehension is vivid, retentiveness strong, and our recollections of that time, like those of a time spent in rapid and interesting travel, are of something intricate, multitudinous, and long-drawn-out. But as each passing year converts some of this experience into automatic routine which we hardly note at all, the days and the weeks smooth themselves out in recollection to contentless units, and the years grow hollow and collapse.

心理学の歴史における古典 - James(1890)Chapter 15

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/prin15.htm私たちが年を取るにつれて、同じ時間間隔が短く見えます。つまり、日、月、年がそうです。 時間がそうであるかどうかは疑わしい、すべての出現への分と秒はほぼ同じままです。

彼の記憶の中で多くのルストラを数える者は、過去5年間のうちの最後のものが、前の等しい量の期間よりはるかに速く走っていることを知ることだけを疑う必要があります。それは世紀の空間であり、過去8〜10年の人生と比較すると、それは1時間のスペースです」

したがってPaul Janet教授( 36 )は、謎を解消するとは言い難い解決法を教えています。 法律があり、人生のある時代のある区間の見かけの長さは人生の全長に比例すると彼は言います。 10人の子供は、彼の一生の10分の1の年であると感じています.50人の人は50人であり、人生全体は一定の長さを保っています。 この式は大まかに現象を表現していますが、それは事実ですが、基本的な精神的な法則ではないでしょう。 大部分は少なくとも、私たちが年を重ねるにつれて短縮される年数は、記憶の内容の単調さに起因し、結果的に後ろ向きに見えるビューを簡素化するためです。 青少年には、毎日のように、主観的または客観的に全く新しい経験があるかもしれません。 不安は鮮やかで、保持力は強く、その時間の思い出は、すばやく興味深い旅行に費やされた時間のように、複雑で、多数で、長く描かれたものです。 しかし、この経験のいくつかは、毎回のことではなく、私たちがほとんど気づいていない自動ルーチンに変換されるので、日と週は無意味なユニットへの想起の中でスムーズになります。

Revue Philosophique、vol。 III。 p。 496。

・『心理学. 上』(W.ジェームズ 著 ; 今田寛 訳 岩波書店 1992.12)

・『心理学. 下』(W.ジェームズ 著 ; 今田寛 訳 岩波書店 1993.2)

上記の2冊は”The principles of Psychology”の短縮版にあたるらしい

国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション - 心理学. 下巻

http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/8797770 #17?

https://ja.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%A6%E3%82%A3%E3%83%AA%E3%82%A2%E3%

83%A0%E3%83%BB%E3%82%B8%E3%82%A7%E3%83%BC%E3%83%A0%E3%82%BA

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/ウィリアム・ジェームズ

ウィリアム・ジェームズ(William James、1842年1月11日 - 1910年8月26日)は、アメリカ合衆国の哲学者、心理学者である。意識の流れの理論を提唱し、ジェイムズ・ジョイス『ユリシーズ』など、アメリカ文学にも影響を与えた。パースやデューイと並ぶプラグマティストの代表として知られている。弟は小説家のヘンリー・ジェームズ。著作は哲学のみならず心理学や生理学など多岐に及んでいる。

日本の哲学者、西田幾多郎の「純粋経験論」に示唆を与えるなど、日本の近代哲学の発展にも少なからぬ影響を及ぼした。夏目漱石も、影響を受けていることが知られている。後の認知心理学における記憶の理論、トランスパーソナル心理学に通じる『宗教的経験の諸相』など、様々な影響をもたらしている。

VI

The next objection is more formidable, in fact it sounds quite crushing when one hears it first.

If it be the self-same piece of pure experience, taken twice over, that serves now as thought and now as thing

— so the objection runs — how comes it that its attributes should differ so fundamentally in the two takings. As thing, the experience is extended; as thought, it occupies no space or place. As thing, it is red, hard, heavy; but who ever heard of a red, hard or heavy thought? Yet even now you said that an experience is made of just what appears, and what appears is just such adjectives. How can the one experience in its thing-function be made of them, consist of them, carry them as its own attributes, while in its thought-function it disowns them and attributes them elsewhere. There is a self-contradiction here from which the radical dualism of thought and thing is the only truth that can save us. Only if the thought is one kind of being can the adjectives exist in it

intentionally

(to use the scholastic term); only if the thing is another kind, can they exist in it constituitively and energetically. No simple subject can take the same adjectives and at one time be qualified by it, and at another time be merely of

it, as of something only meant or known.

The solution insisted on by this objector, like many other common-sense solutions, grows the less satisfactory the more one turns it in one's mind. To begin with, are thought and thing as heterogeneous as is commonly said?

No one denies that they have some categories in common. Their relations to time are identical. Both, moreover, may have parts (for psychologists n general treat thoughts as having them); and both may be complex or simple. Both are of kinds, can be compared, added and subtracted and arranged in serial orders. All sorts of adjectives qualify our thoughts which appear incompatible with consciousness, being as such a bare diaphaneity. For instance, they are natural and easy, or laborious. They are beautiful, happy, intense, interesting, wise, idiotic, focal, marginal, insipid, confused, vague, precise, rational, causal, general, particular, and many things besides. Moreover, the chapters on Perception

in the psychology-books are full of facts that make for the essential homogeneity of thought with thing. How, if subject

and object

were separated by the whole diameter of being,

and had no attributes and common, could it be so hard to tell, in a presented and recognized material object, what part comes in thought the sense-organs and what part comes out of one's own head

? Sensations and apperceptive ideas fuse here so intimately that you can no more tell where one begins and the other ends, than you can tell, in those cunning circular panoramas that have lately been exhibited, where the real foreground and the painted canvas join together.

Essay I § 6, n. 1: Spencer's proof of his Transfigured Realism

(his doctrine that there is an absolutely non-mental reality) comes to mind as a splendid instance of the impossibility of establishing radical heterogeneity between thought and thing. All his painfully accumulated points of difference run gradually into their opposites, and are full of exceptions. [Cf. Spencer: Principles of Psychology, part VII, ch. XIX.]

漱石(01):夏目先生が、ウィリアム・ジェイムズの心理学について知ったのは、1900年前後のこと。 ( その他人文科学 ) - 禅膳はぜんぜん。 - Yahoo!ブログ

https://blogs.yahoo.co.jp/zenaway/63477816.html?__ysp=44Km44Kj44Oq44Ki44Og44K444Kn44Kk44Og44K6IOWkj%2Bebrua8seefsw%3D%3D著者のお二人、宮本盛太郎さんも関静雄さんも京大大法学部卒の政治学者ですが、文学にも大変ご興味があって、夏目漱石を研究されているという大変に羨ましい御仁です。主とした参考文献は以下のようです。

岡三郎、「夏目漱石研究」、国文社、1986

荒正人(著)、小田切秀雄(監修)、「増補改訂:漱石研究年表」、集英社、1984

小倉脩三、「夏目漱石―ウィリアム・ジェームズ受容の周辺」、有精堂、1989>に書かれているところによれば、漱石の蔵書のなかにジェームズの英文著書は三部四冊あると。「心理学原理(2巻、1901)」、「宗教的経験の諸相(1902)」、「多元的宇宙(1909)」である。購入時点は、「心理学原理」が1902年5月で、「宗教的経験の諸相」はその少し後である、という。

『文学論』の講義が始まったのは1903年9月であるが、その講義の第一編「文学的内容の形式」に、「心理学原理」と「宗教的経験の諸相」からの引用が見られると。(鶴見俊輔さんや外山滋比古(とやま しげひこ)さんが触れておられた、例の『文学論』である。)

針生和子、「夏目漱石―初期評論と『哲学(会)雑誌』との関連を中心とした」、(比較文学講座Ⅳ『日本近代評論―比較文学的にみた』、清水弘文堂、1974)所載によると、夏目漱石は1890(明治23)年9月に帝大に入学し、91年8月から93年8月まで、『哲学(会)雑誌』の編纂委員を勤めている。『哲学会雑誌』は92年から『哲学雑誌』と改題。また、ほぼ同時期に、松本亦太郎もこの雑誌にたずさわっている。

針生氏によると、漱石がかかわる以前の『哲学会雑誌』で著しく目に付くのは、心霊現象の解明であり、従来迷信とされていたこの心霊現象を、心理学で科学の対象として研究課題として頻繁に取り上げていると。

また、この『哲学(会)雑誌』で、1890年1月に、その雑録でジェイムズの名前が初出する。1892年の大西祝の論説「心理説明」で、ジェイムズの心理学が具体的に紹介されている。針生氏の上記からの引用を再録すると、

<漱石が編纂委員として登場する明治二十四年八月までには、哲学科における欧米の心理学の積極的な輸入によって、意識を研究対象としてその学問領域がかなり開拓されている。意識は二重で・・・・顕在意識的なものと潜在意識的なものから成立し、潜在意識的事実として、不可思議現象が新たに科学の対象となった。おそらく、元良勇次郎あたりによって、意識という用語も定着したと思われる。

・・・・こうした学問状況の中に入学した漱石は、講義で心理学に接触する可能性があったし、『哲学会雑誌』の雑録、雑報、批評紹介欄を担当していた心理学専攻の編纂委員仲間(松本亦太郎)から、意識について、さらにはジェームスについての知識を得、また記事および論文も読んだ可能性もあったろう。したがって、漱石は(1891年)明治二十四年八月ころには、意識観念に関心を持ち、またあるいはジェームスの名前も知っていた可能性もあるのである。

見当としては、『哲学会雑誌』の編纂委員をであった1891年(明治24年)から、「心理学原理」や「宗教的経験の諸相」を購入して読んだであろう1902年(明治35年)の時期にかけてのおおよそ10年間に、だんだんに、夏目漱石はウィリアム・ジェームズの心理学について知ったと言っていいであろう。つまり、1900年前後には漱石はウィリアム・ジェームズを知っていたと。

Descartes for the first time defined thought as the absolutely unextended, and later philosophers have accepted the description as correct. But what possible meaning has it to say that, when we think of a foot-rule or a square yard, extension is not attributable to our thought? Of every extended object the adequate mental picture must have all the extension of the object itself. The difference between objective and subjective extension is one of relation to a context solely. In the mind the various extents maintain no necessarily stubborn order relatively to each other, while in the physical world they bound each other stably, and, added together, make the great enveloping Unit which we believe in and call real Space. As outer,

they carry themselves adversely, so to speak, to one another, exclude one another and maintain their distances; while, as inner,

their order is loose, and they form a durcheinander in which unity is lost.But to argue from this that inner experience is absolutely inextensive seems to me little short of absurd. The two worlds differ, not by the presence or absence of extension, but by the relations of the extensions which in both worlds exist.

Essay I § 6, n. 2: I speak here of the complete inner life in which the mind plays freely with its materials. Of course the mind's free play is restricted when it seeks to copy real things in real space. ↩

Does not this case of extension now put us on the track of truth in the case of other qualities? It does; and I am surprised that the facts should not have been noticed long ago. Why, for example, do we call a fire hot, and water wet, and yet refuse to say that our mental state, when it is of

these objects, is either wet or hot? Intentionally,

at any rate, and when the mental state is a vivid image, hotness and wetness are in it just as much as they are in the physical experience. The reason is this, that, as the general chaos of all our experiences gets sifted, we find that there are some fires that will always burn sticks and always warm our bodies, and that there are some waters that will always put out fires; while there are other fires and waters that will not act at all. The general group of experiences that act, that do not only possess their natures intrinsically, but wear them adjectively and energetically, turning them against one another, comes inevitably to be contrasted with the group whose members, having identically the same natures, fail to manifest them in the energetic

way. I make for myself now an experience of blazing fire; I place it near my body; but it does not warm me in the least. I lay a stick upon it, and the stick either burns or remains green, as I please. I call up water, and pour it on the fire, and absolutely no difference ensues. I account for all such facts by calling this whole train of experiences unreal, a mental train. Mental fire is what won't burn real sticks; mental water is what won't necessarily (though of course it may) put out even a mental fire. Mental knives may be sharp, but they won't cut real wood. Mental triangles are pointed, but their points won't wound. With real

objects, on the contrary, consequences always accrue; and thus the real experiences get sifted from the mental ones, the things from out thoughts of them, fanciful or true, and precipitated together as the stable part of the whole experience-chaos, under the name of the physical world. Of this our perceptual experiences are the nucleus, they being the originally strong experiences. We add a lot of conceptual experiences to them, making these strong also in imagination, and building out the remoter parts of the physical world by their means; and around this core of reality the world of laxly connected fancies and mere rhapsodical objects floats like a bank of clouds. In the clouds, all sorts of rules are violated which in the core are kept. Extensions there can be indefinitely located; motion there obeys no Newton's laws.

Essay I § 6, n. 3: [But there are also mental activity trains,

in which thoughts do work on each other.

Cf. below, p. 184, note. Ed.] ↩

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home