以下、It's Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

の機械翻訳。

追記

その後和訳が出た

https://vicryptopix.com/mp3-mmt/

参考リンク:

https://www.economicprinciples.org/downloads/bw-populism-the-phenomenon.pdf

参考リンク:

https://www.economicprinciples.org/downloads/bw-populism-the-phenomenon.pdf

金融政策3の特徴(後述):

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

ーーー

| 最も直接的 ⬆︎ ど の 程 度 直 接 的 に 刺 激 を 受 け る か ? ⬇︎ 最小 |

中央銀行は印刷されたお金を直接政府に提供します

債務が「回収」されたQE[量的緩和](政府は返済する必要はありません)

中央銀行は、財政支出を実施する準民間企業(開発銀行など)に融資します。

|

直接借入金ジュビリー

間接債務 "Jubilee[特赦]"(金額の切り下げにより債務返済の実質コストを削減)

実物資産を購入するQE(例:公園を建設するための土地の購入)

|

中央銀行は世帯に直接印刷された現金を提供します(ヘリコプターのお金)

中央銀行は税率をある程度管理し、印刷されたお金で減税に資金を供給している

極端にマイナスの金利、世帯に渡される

中央銀行は、銀行が終焉するための非常に強力な経済的インセンティブを提供します。

|

| 公共部門をターゲットにしている | [公共部門と民間] 両方 |

民間セクターをターゲットにしている

| |

| 誰が刺激を受けるか? | |||

金融政策3(MP3)とMMT(現代貨幣理論)のレイ・ダリオの主張を和訳

MP3 MMT

by Ray Dalio

金融政策3(MP3)とMMT(現代貨幣理論)のレイ・ダリオの主張を和訳

この記事はアメリカの著名な投資家であるレイ・ダリオが、金融政策3(MP3)とMMT(現代貨幣理論)について詳細に記述した下記の記事を基にしています。

限りなく、原文に近い表現を使うように心がけていますが、多くの部分を理解しやすいように可能な限り意訳しています。彼の主張は、既存の政策の枠組みを覆す意見でありながら、過去の歴史を辿ればその意見に行き着くことが不可避であることが理解できるはずです。以下、原文の和訳です。

なお理解には経済の基本的な仕組みを理解しておく必要があります。下記リンクで詳しく解説しています。

この記事は、特に金融政策と財政政策が今後どのように機能するかについて、関心を持つ人のためのものです。

この記事では、金融政策3: MP3(我々が世界中でもっとも目にする新しいタイプ)とMMT(かなりの注目を集めている最近提案された新しいアプローチ)に焦点を当てます。

そして、この記事は二つのパートで構成されます。パート1では、金融政策3(MP3)とMMTについて述べます。パート2では歴史的なケースを示します。

当サイトからお申し込みの多い取引所はこちら

パート1:MP3とMMTについて

私が経済とマーケットを、機械的な方法で観察します。エンジニアが機械の因果関係を観察するのと同じようにです。私にとって、経済的機械は限られた数の基本的な因果関係で成り立ちます。(「経済的機械の仕組み」を参照)

これは、「アルファベットの26文字」を組み合わせて無限の単語を構成することができるのと同じように、無限の組み合わせを作れる「数多くの方法」でまとめることが可能です。

より具体的には、経済政策には、金融政策と財政政策の2つの基本的な構成要素があり、その配下には、いくつかの方法(財政政策の課税と支出、および金融政策の金利と量的緩和(QE)と引き締め)があります。

これらのうち、それらを設計可能な様々な方法があります。全体像では、金融政策によってシステム内の総額とクレジット(つまり消費力)が決まり、財政政策によって、政府の税金獲得の方法と税金の支出への影響が決まります。

私にとって、世界で最も重要な「工学パズル」の政策決定者は、金融政策がうまくいかないときに、多くの人に経済的な幸福を生み出すために経済的機械をどのように作るかということが重要です。

金利引き下げ(MP1)と量的緩和(QE)は効果がない

金融政策がまったく機能しないわけではありません。しかし、金利引き下げ(金融政策1と呼ぶ)や量的緩和(金融政策2と呼ぶ)を通じて、経済活動を刺激するという、慣れ親しんだ方法では、経済的繁栄には、ほとんど効果がありません。

それは、お金とクレジットの成長(すなわち、支出力)を生み出すのに効果的ではなく、そして、多くの、そして大多数の人の生産性と繁栄を高める効果がほとんどないからです。

ですから、私たちは金融政策3(MP3)をとらなくてはいけません。この政策は、私たちはあまり慣れ親しんでいませんが、遠く離れた場所では様々な形で存在していました。

つまり、財政政策と金融政策の調整です。金利が0%に固定されているときや量的緩和が目標を達成するのに効果的でないときに、中央銀行は、さらに緩和しようとすることは避けられません。私は最近、過去の事例とそのような調整の将来の可能性についての以前の調査を刷新しました。それらを以下に共有します。

MMTは数ある金融政策の一つ

MMT(現代貨幣理論)は、避けられない考え方の無限の方法のうちの1つです。現代貨幣理論が何であるか知らない方は下記で記述しています。(リンク)

MMTは、様々な人によって、様々な記述がされています。たとえば、学生のローンを撤廃するために使用される富裕税があるように財政政策を変えるという人もいれば、他の方法で税金や支出を変えるという人もいます。この段階では詳しく調べない方が賢明です。あまり調べすぎると、重要なことを見る上で邪魔になります。また、パッケージとしてMMTに焦点を当てている人々は、MP3ポリシーのより広い範囲について考えるのではなく、そのパッケージの最善の詳細を考えることだけに考えが制限されます。

MMTの最も重要な構成要素は、金利を0%に固定することであり、財政政策の黒字と赤字のコントロールによってインフレを厳格に管理することであり、つまり、債務を生み出し、中央銀行がお金を生み出すということです。

言い換えれば、柔軟に動く金利と、財政赤字(しばしば)と財政黒字(めったにない)は非常に密接に関わり、金利は購買力とサイクルを生み出す上でとても重要でしたが、将来的には、利子率は0%に固定化され、財政政策は、より流動的かつ重要になり、赤字によって生み出された債務は、貨幣化され、お金を生み出すこととなります。

気づかなくとも、それは概して起こっていることであり、ますます将来的には必要性に迫られます。言い換えると、すでに、3つの主要準備通貨のうち2つ(ユーロと円)で金利が0%近くに固定されているため、次は、3番目の最も重要な準備通貨(ドル)でも、0%に固定化される可能性が高いです。

その結果、財政政策の赤字によって、貨幣化(通貨発行)されることとなります。つまり、ずっと前から現代貨幣理論(MMT)のコンセプトは存在しました。MMTという名前は別ですが。

MMTとはつまり

- 金利を0%前後に固定する

- 債務の貨幣化(通貨発行)を伴うより柔軟な財政政策

- 厳格なインフレターゲティングによる財政赤字の補填

これらの構成要素が、すでに存在することは事実です。準備通貨の国々では、必要とされる政策であり、そして実現可能です。

このアプローチの付加的な利点は、中央銀行が金融資産を持っている人々から中央銀行が金融資産を購入して、金融資産を持つ人が中央銀行から得たお金を使用するプロセスよりも、作成されたお金とクレジットが望ましい用途に資金を提供することができる点です。

この政策の歴史的な例はたくさんあります(ご存じのように、1930年代から1940年代の戦前と戦争の時代を見れば、非常に似ています)

このアプローチの大きなリスクは、政治的に選出された政策決定者の手に資金、クレジット、そして支出を生み出し、配分する力を与えることのリスクから生じます。

私の意見では、これらのMP3ポリシーをうまく機能させるためには、意思決定が賢明で政治的な動機のない、熟練した人々の手に渡るようにシステムを設計する必要があります。それを達成するためのシステムの構築方法を想像するのは困難です。しかし、同時に、私たちがこの方向に向かっているのは避けられません。

MP3とMMTについての私達の考え

次のセクションでは、MP3についての私の考えをより詳細に概説します。私と私のBridgewaterの同僚が真実であると信じる主なポイントは以下のとおりです。

- 財政政策は次の景気後退に十分な刺激を与えるために金融政策と結び付かなければいけないという考えに我々は同意します。これは、金融政策1(金利の移動)ではほとんどの場合単独ではほとんど効果がなく、金融政策2(中央銀行の「印刷」および金融資産の購入に基づく)で刺激する事となります。「大きな債務危機を乗り越えるための原則」で説明している理由から、各国の債務が自国通貨建てである限り、金融政策と財政政策の組み合わせが景気後退を円滑化するために役立つ可能性があります。ただし、経済政策立案者の能力が限られていることや、正しいことをする政治的能力が限られていることが、妨げにもなります。

- 私たちは財政と金融政策の調整を金融政策3(MP3)として説明しました。そしてこれは金利引き下げ(MP1)とQE(MP2)が有効でないときに重要な政策ツールです。金利の引き下げとQEは、他のところで詳細に説明した理由から、次の景気後退ではそれほど効果的ではないと判断します。我々はまた、金融政策が適切なトリクルダウンを生み出しているとは考えていません。QEと金利の引き下げは、資産価格の引き上げを助け、すでに多くの資産を所有している人を助けます。逆に非資産家は助けません。これらのレバーは、教育、インフラ、研究開発などの良い投資になるものにお金を向けることはしません。

- 財政政策は、非資産家層に投資を扱う方法です。しかし、景気後退時に財政政策に頼ることの問題は(それが非常に政治的に請求されていることを除けば)それは対応が遅いということです。それは長いリードタイムを持ちます。つまりプログラムを作らなければなりません。

- 例えば、それが半自動調整機のように、金利が動くのと同じように、税金が動く状態を想像してみてください。不況が発生した場合は、税金も自動的に引き下げられます。反対に、引き締めは税の上昇をもたらすでしょう。

- 資金不足で、投資収益率が高い分野(教育、インフラ、研究開発など)へ半自動で投資が増加することを想像することができます。 企業や投資家にとって最も収益性の高い分野を金融市場を通して資金を供給するの方法ではありません。

- 中央銀行が印刷したお金で、それらに資金を供給することは、中央銀行が赤字を貨幣化で賄うので、政府がより大きな借金をもたらし、より高い金利をもたらすという典型的な問題について心配する必要がないということです。これまでに何度か説明し、2008年の金融危機以降に見てきたように、貨幣化(通貨の発行)によってインフレが大きくなりすぎることはありません。それは、インフレは、「支出の総量」を販売された「商品やサービス」の量で割った値で決まるからです。印刷されたお金が景気低迷の中で起こるクレジットと支出の減少の一部を単に相殺するのであれば、それはインフレを生み出さないでしょう。

- 大きな問題は、これらのレバーをうまくコントロールするために誰が信頼できるのかということです。(中央銀行?連邦政府?)これらのツールはより良くする力を持っていますが、責任を持って使われなければ、害を及ぼします。そのため、ガバナンスと決定権は慎重に設計する必要があります。これは私がここでは説明しない大きなトピックです。

- 多くのMMT支持者が主張している一つの特定の政策は、雇用保障プログラムです。それが実際にどのように行われるかに大きく依存します。表面的なレベルでは、雇用の継続は一般的に人々の心理学/精神的健康、そして良い結果を生み出すために重要であるため、経済的不況で政府の仕事を通してお金を稼ぐために働く人々の考えには好感が持てます。(互いに助け合い、都市が綺麗になるように)

私が同意しないMMTの二つの考えがあります。

- 企業がコストに基づいて投資を行うのではなく、単に事業の見通しに基づいて意思決定を下すという考えには同意しません。資金調達コストと事業見通しの両方が重要です。資金調達コストは、物事を遂行する事業の決定に大きな影響を与えます。たとえば、資金調達コストが低いことが、米国企業が大量の自社株買いを行った理由です。

- MMTの中には、インフレを主に企業の過度な価格決定力のせいにする人もいます。それがインフレに影響を与えるかもしれませんが、もっと重要なのは、何か(労働力、商品など)の不足とそれに対する過度の需要があるとき、価格が上がるということです。

金融政策3(MP3)とは何か?

私が述べたように、過去数回のサイクルで経済を刺激するのに十分であった政策ツールは、おそらく今度は十分ではないでしょう。

金融政策1(金利の引き下げ)は、先進国全体での非常に低い/マイナスの金利によって制限されています。

金融政策2(量的緩和)は、すでに非常に低い長期金利/資産の期待収益率と、現在の政治的制約を考慮して購入可能な債券が少なくなっている一部の中央銀行(特にECB)によって制限されています。

また、金融資産を持っていない人々にお金やクレジットを付与するには効果的ではなく、格差の拡大にもつながります。これらの理由から、私は次の不況では先進国は「金融政策3」(MP3)に目を向ける必要があると思います。

この研究では、金融政策3を定義します。金融政策3は、投資家/貯蓄者(MP1とMP2が主に対象としているグループ)よりも浪費家に向けられている金融政策で構成されています。

言い換えれば、浪費家がお金を使うように印刷されたお金を提供する政策です。この種の政策は、間違いなく中央銀行と政府の双方にとって政治的に物議をかもしています。

大きな問題は、これらの政策が生産性を損なうか、あるいは助けるかどうかです。「大きな借金の危機を乗り越えるための原則」という本で説明されている理由から各国が自国通貨建ての債務を抱えている限り、これらの政策は景気後退を円滑にするのに役立つ可能性があります。

「増加した生産性」が生産され費やされた「お金とクレジット」の量を超える場合は、正しいことをしなくてはいけません。だからこそ、政策立案者がこれらの政治的/その他の障害を乗り越えて「プランB」を策定することが重要なのです。

財政プログラムなどに資金を提供する、さもなければ、経済が衰退したときにこれらの政治的な考慮事項を通して働くことは不適切なリードタイムを提供するかもしれません

以下に、これらのMP3ポリシーがどのような形式をとることができるかについての私達の以前の研究のいくつかを共有し、最近のいくつかの例で更新します。

金融政策3の定義

MP3とは、

- お金を受け取る人

民間部門と公共部門 - 印刷されたお金を提供する方法

消費者への間接的な資金提供手段と直接的な資金提供手段、例えば「ヘリコプターマネー」)

によって分類できます。

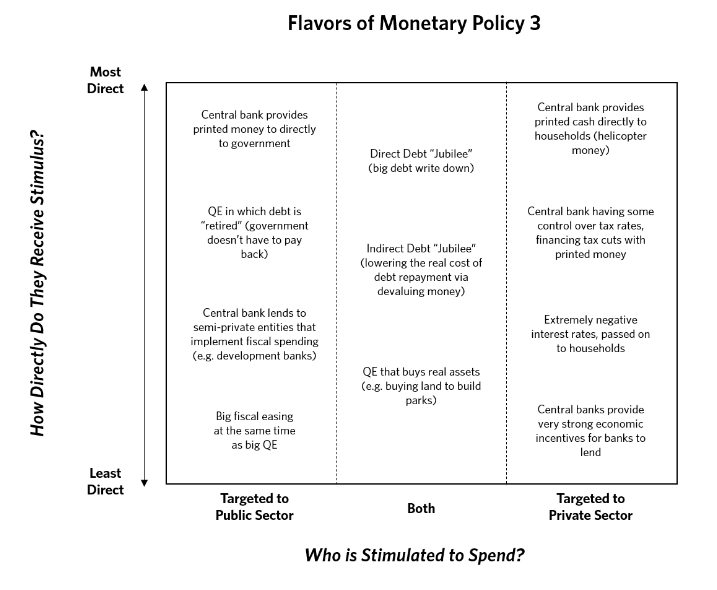

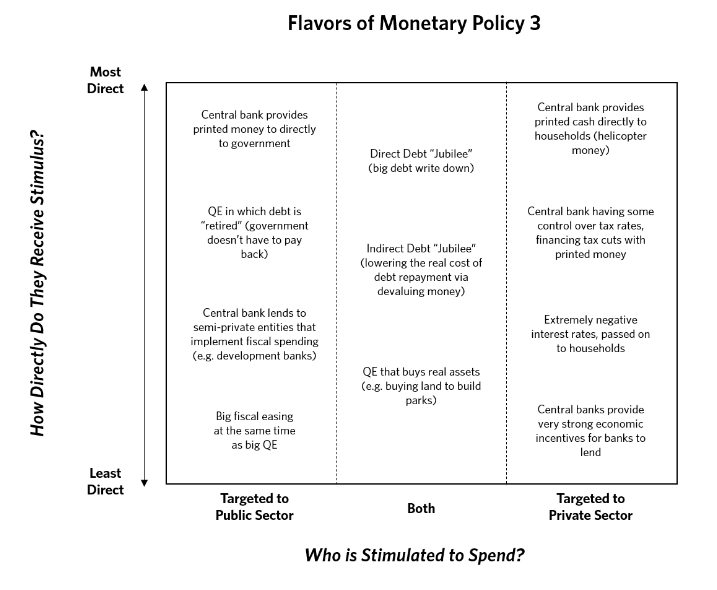

次の図は、考えられる多くの種類のMP3をマトリクスでマッピングしています。一般的に、より直接的な政策ほど、効果的ですが、政治的には困難です。そして、最も直接的でない政策(あるいはそれらの変種)のいくつかが最近使われました。しかし次の重大な不況で必要とされるであろう規模ではありませんでした。

まず、公共部門を対象とした MP3政策を解説します。これらの政策をより詳しく(政策が使用されたいくつかの歴史的事例を含めて)見ていきます。

- 最も直接的な選択肢は、債務による資金調達で財政支出を増やすことです。新規発行債権の大部分を購入するQEとペアの政策です。(例えば、1930年代の日本、第二次世界大戦中の米国、そして2008年の金融危機後のほぼすべての先進国で起きました)

- 中央銀行は、開発銀行またはその他の民間/半民間企業に貸付/資本化することができます(たとえば、2008年の中国)。財政を刺激できるプロジェクトに投資します。

- 最後に、中央銀行が政府のプログラムに資金を提供することを明確に目的としている場合には、直接的な財政的/金銭的調整があり得ます。次の通りです。

- 財務省が借金に追いついていない、借金による財政支出の増加。

- 支出は、中央銀行が債務を回収するか、または債務を永遠に延期することを約束するQEとペアになります。

- 中央銀行は借金の支払いをカバーするためにお金を印刷することを約束しています(例えば1930年代のドイツ)または

- 借金の発行を煩わさずに、印刷したばかりのお金を直接政府に渡します。過去の事例には、通貨の印刷(例:中国、アメリカ独立戦争、1930年代のアメリカ南北戦争、ドイツ、第一次世界大戦中のイギリス)、または通貨の引き下げ(古代ローマ、中国、16世紀イギリス)が含まれています。

下記のMP3ポリシーは、民間部門と公共部門の両方での支出をサポートしています。以下は実例です。ちなみに、私達はこれらのどれも推奨していません。具体的な例を以下に示します。

- QEは不動産や他の実物を購入するのに使われるかもしれません、そしてそれは理想的に社会的に有益な目的のために使われるでしょう。たとえば、デトロイトで放棄された土地を購入し(個人の土地所有者をサポートする)、公園を建設するためにそれらを破壊します。

- 多額の資金創出を伴う多額の負債評価減(「ジュビリー年」借金の帳消し)

- この直接的ではないバージョンは、長期にわたって債務の実際の価値を下げるために、より高いインフレまたは通貨切り下げを明示的に目標とすることによるものです。

- レバーとして通貨介入/減価償却を明示的に使用する中央銀行はこれを助けるでしょう。

例えば、大恐慌の間のドル切り下げ(金連動債務を無効にする)は、事実上、大きな債務償却を生み出しました。 - 場合によっては、政府が債務の評価減を直接作成または交渉する。(例えば、古代ローマ、大恐慌、アイスランドなど)

下記のMP3ポリシーは民間部門を対象としています。

- MP3は銀行を通じて機能する可能性があり、貸付に対する非常に強いインセンティブを提供します。例えば、超過準備金にマイナス金利を付与することです。それは、つまり、より高い収益を求めて銀行が融資するようになります。このプログラムのフレーバーは、最近ヨーロッパ、日本、そしてイギリスで試みられました。

- これを達成するための別の方法は、補助金を受けたローンまたは保証を通して借りるように人々を動機付けることです。その一例が英国の「購入支援」プログラムで、一部の住宅購入者に不動産価値の最大20%までの5年間の無利子融資を提供しています。

- これまでのところ、否定的な意見が多いですが、中央銀行は、世帯が現金を保有するのを妨げて世帯に支出を促すように実験をすることができます。

例えば、ある人は、負の利子率で現金を保有することに対する「帳簿税」を提案している(これはヨーロッパで大恐慌の間に実験された)。

また別の人は、物理的なお金を無効にして、すべての現金保有物に負の金利を適用することを、簡単にするためだけにデジタルなお金を使うことを提案しました。明らかにこれは極端でしょう。 - 中央銀行は、ある範囲内で、所得税率や売上税率の変更を管理できます。それから彼らはそれを経済を管理するための追加的な反循環的なレバーとして使い、不況時の税金を引き下げ(マネープリントとペアにする)、そして適時に税金を引き上げることができます。

- お金を印刷し、世帯に直接現金を渡す方法もあります。(すなわち、ヘリコプターマネー)。 私たちがヘリコプターマネーに言及するとき、それはお金を浪費家の手の中に向けることを意味します(例えば、大恐慌の間のアメリカの退役軍人のボーナス、中国)。

- 基本的な変種は、

a)全員に同じ金額を渡すか、または1つ以上のグループを他のグループよりもある程度手助けすることを目的とする(たとえば、裕福な人々よりも貧しい人々に)のいずれかです。

b)このお金を一時的なものとして、または時間をかけて(おそらく普遍的な基本収入として)提供することです。この変種として、1年以内に使われなければお金が消えるように、それを使う動機と対になることがあります。 - お金は、社会的に望ましい支出/投資に向けてそれをターゲットにするために、特定の投資口座(退職、教育、または中小企業投資のために割り当てられた口座のような)に向けられるかもしれません。

- 政策を策定するための1つの可能性のある方法は、QEからのリターン/保有を政府ではなく世帯に分配することです。

- ヘリコプターマネーの変種として、中央銀行は資産価格をさらに引き上げ支出を支援するために、最低下落率(ドローダウン)を定めたり、株式やリスクの高い資産の収益率を保証することができます。

繰り返しになりますが、これらの相対的なメリットについては何もコメントしておりません。

政策決定者の立場にあれば、おそらく知っている過去の事例についての知識を示しているだけです。次に、これら政策を審査するプロセスでは、各国で何が合法で、何が政治的に許容できるのかを検討する必要があります。

最善の結果を出すのは大変な仕事ですから、時間がかかります。その結果、政策立案者、特に中央銀行は、これを解決するために懸命に取り組む必要があると考えています。

私たちは、これらについて意見を述べることはしませんが、最も効果的なアプローチは財政/通貨の相互の調整であるという意見を提供します。

なぜなら、お金の提供と支出の両方が起きることを保証するからです。中央銀行が人々にお金(ヘリコプターマネー)を与えるだけでは不十分です。お金を使うインセンティブを付与するのが賢明です。しかし、時々、金融政策の決定者が財政政策を決定する人々と調整が困難な場合、他のアプローチが使用されます。 そのようなケースでは、それらが2つ以上の要素を持っていて、それらが上で言及されたマトリクスに入らない可能性があります。

MP2(QE)とMP3の間に明確な境界線さえありません。たとえば、政府が減税をする場合、それはおそらくヘリコプターマネーではありませんが、その資金をどのように供給したかに依存します。政府が浪費家として行動し、中央銀行が、その資金を供給したのならば、それは財政の経路を通じたヘリコプターマネーと言えます。

パート2:歴史的事例

MP1とMP2は効果的でなかった、多くの歴史的事例を見ていきます。そして、MP3に関する歴史的事例を示します。

世界大恐慌時の金融政策3を掘り下げてから、いくつかの他のケースを見てみます。それは非常に長く広範な分析なのでwww.economicprinciples.org で記載しています。

しかし、世界大恐慌で起こったことは、今日の環境に類似した最も最近の事件であるので、下記に示します。

しかし、世界大恐慌で起こったことは、今日の環境に類似した最も最近の事件であるので、下記に示します。

付録:金融政策の歴史的事例の詳細

MP3に関する原則を下記の例で示します。

事例: 1930年代のアメリカ

ルーズベルト大統領の政策、特に1933年の金とドルの切り下げは、「美しいレバレッジ解消」を生み出しました。実際、その年の「ひもを押す(暖簾に腕押し)」という言葉は、FRB議長のMarriner Ecclesに疑問を投げかける米国の代表によって造られました。

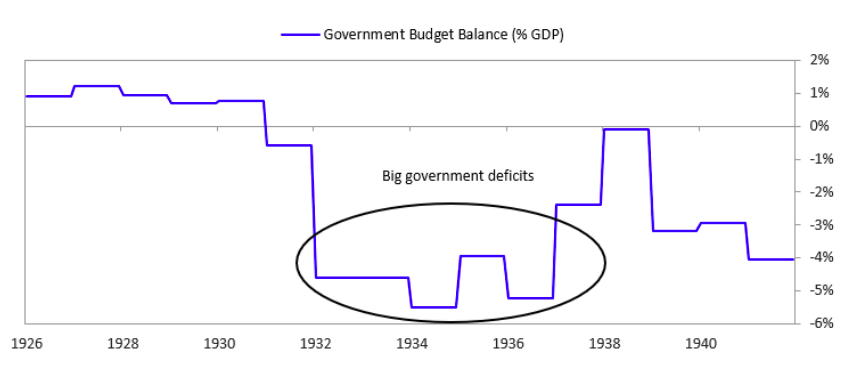

このセクションでは、米国がどのようにしてMP1とMP2(低金利とお金の増加)を調整した創造的な財政政策で補完し、1937年の不況から抜け出すために財政と金融の調整に頼ったかについて述べます。

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

ルーズベルトが最初に行った大きな財政政策の転換の1つは、彼の「美しいレバレッジ解消」の一環として、巨額の負債評価減を処理することでした。彼はそれをいくつかの異なる方針で行いました。

第一に、米国は債務契約から「金条項」を排除する法律を可決した。それまでは、ほとんどの長期借入金に金の指数表示条項がありましたが、これは切り下げによって名目上の債務負担が大幅に増加することを意味していました。その条項を廃止することで、ドルが下落しても債務負担が同じになり、事実上、広範囲にわたる債務再編が生まれました。もちろん、それは政府が債権者を犠牲にして債務者に利益をもたらすような方法で契約を破ることを法律で制定したことを意味しました。この事件は最高裁判所に持ち込まれ、政府の賛成で5-4で可決しました。

第二に、1933年にルーズベルトはアンダーウォーター住宅ローンの借り手を支援する機関、住宅所有者ローン公社(HOLC)を設立しました。この機関は、抵当貸付を政府保証付き債券と交換し、抵当権実行額を上回る抵当を購入し、貸し手の参加を促しました。その後、HOLCは住宅ローンを再構築し、金利を引き下げ、ローン期間を15年まで延長します(住宅ローンの期間は通常5年から10年)。場合によっては、HOLCは元本を減らして、借り手のローン対価値(LTV)の比率を80%未満に保つこともあります。この機関は、全住宅ローンの約20%を占める100万件のローンを47億5000万ドル(GDPの約8%)を使って購入しました。

ルーズベルトはまた、人々を直接雇用する大規模な政府プログラムも作成しました。最も重要なものは1935年に始まったWorks Progress Administration(WPA)でした。それは第二次世界大戦の始まりまで続き、年間GDPのおよそ2%に等しい支出でした。

WPAは、すべてのプロジェクトが人件費の少なくとも90%を費やすことを義務付けているため、特に雇用に焦点を当てていました。ホワイトカラーや芸術作品のための資金もありましたが、ほとんどのプロジェクトはインフラ関連でした。プログラムは図書館員、音楽家、作家、仕立て屋、教師、研究者、医師、建築家などを雇いました。ピーク時には、労働人口の6%を超える約350万人が雇用されていました。

1936年に更なる刺激があり、早期退役軍人のボーナスが付与されました。このプログラムは、世帯に直接現金で送金するための政府借入の特に良い例です。政府が文字通りしたことは、即時の支払いを受けるか、または満期まで保有することができ、市場を上回る利率を支払うことで、退役軍人に市場性のない債券を提供することでした。また、以前に彼らの将来のボーナス支払いによって政府からお金を借りていた退役軍人は利子を免除されました。

債券の80%が1936年に現金化され、平均的な受取人は当時の個人平均年収を上回る約500ドルを受け取りました。全体として、このプログラムは名目GDPの約2%に相当する財政刺激策でした。

この期間を通じて、米国は財政的インセンティブとマクロプルーデンスの緩和を利用してクレジットと支出を刺激する他の多くのプログラムを展開しました。これらのプログラムは、既存の借り手を支援し、住宅投資のための新たな融資を奨励しました。

- 1932年、連邦議会は準中央銀行として機能し、S&L銀行に資金を提供し、引受基準および担保制限を設定するために連邦住宅ローン銀行制度を創設しました。

- 1933年、住宅所有者ローン法は、20,000ドル以下の住宅で住宅ローンを借り換えることを連邦政府に保証していました。

- 1934年に、連邦準備制度理事会は、株式を購入するための証拠金要件(規制T)を設定する能力を与えられました。それはニューヨーク証券取引所によって最近導入された規則とほぼ同じレベルで、45%の「非常に緩やかな」証拠金要件(後の連邦準備制度の報告によると)から始まりました。

- 1934年に議会は、住宅ローンを保証するために連邦住宅管理局(FHA)を設立しました。1つのFHAプログラムは、5年の満期までの住宅資産を改善するためのローンの20%を保証しました。

- 1934年に、ルーズベルトは36ヶ月までの間家電製品に安いローンを提供するためにEHFAを設立しました(10%の金利、5%の頭金)。

- 1935年、議会は国内銀行のLTVと満期の制限を緩和しました(これまでは最大5年のローンと50%のLTV、現在は10年と60%のLTVのみ)。

- 1937年、連邦準備制度理事会は、景気後退を受けて、自己資本比率の要件を40%に引き下げました(1936年に引き上げられました)。

ルーズベルトの財政支出プログラムは、支出削減(ルーズベルト大統領の初期の段階で軍を削減した)と赤字支出の組み合わせによって賄われていました。

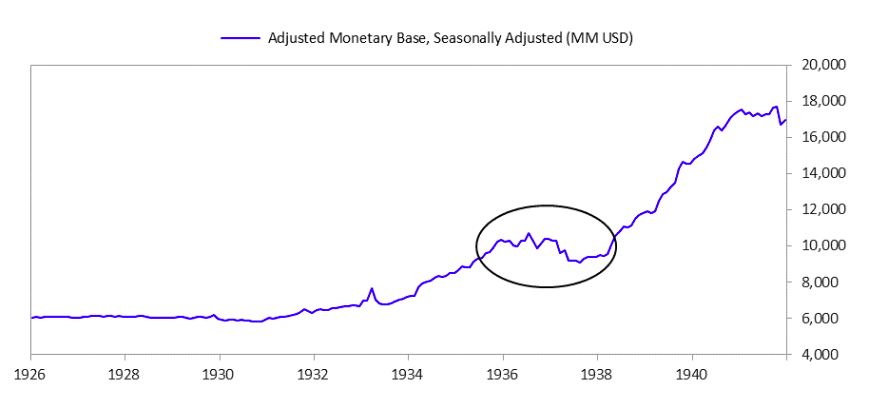

この赤字支出は主に直接QEによって賄われていません。米国の切り下げに続く持続的な金の流入はマネーサプライを増加させました。民間部門への貸付を増やすことを望まない銀行は、政府支出に資金を供給しながらほぼ保証されたスプレッドのために政府債務の保有を大幅に増加させました。

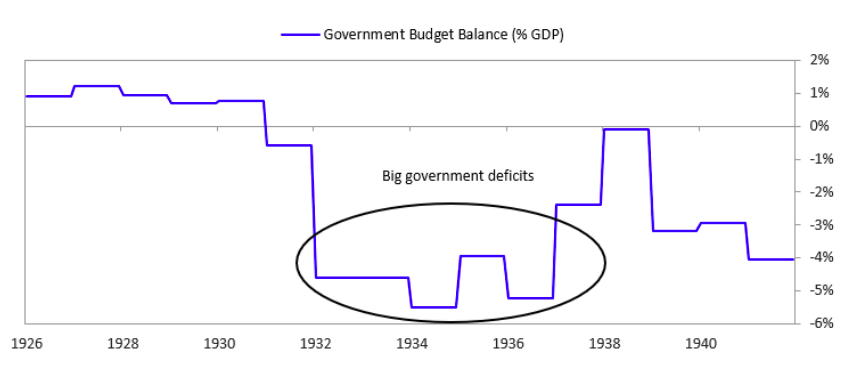

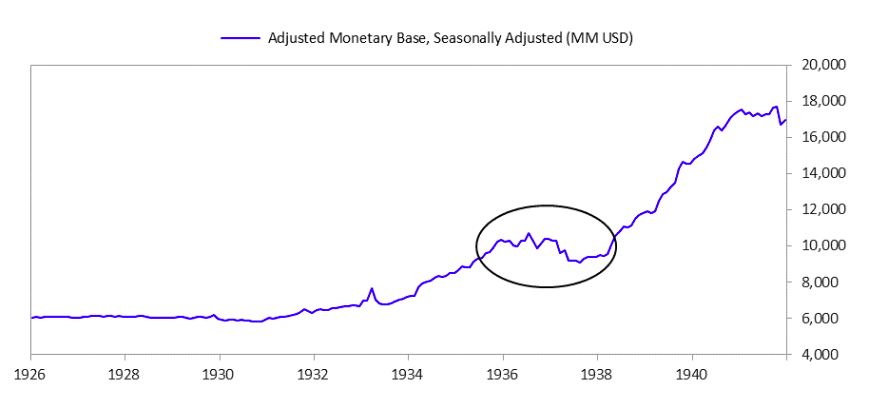

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

1937 - 38年の景気後退に対する政府の対応

1937年、米国株は50%以上の下落、成長はマイナスに転じ、米国はデフレに転落しました。

これまでに説明したように、この低迷の原因については説明しませんが、WPA雇用プログラムの縮小と1936年の退役軍人ボーナスの減退効果が、フランスとイタリアでのドル切り下げとともに大きな貢献をしました。金不胎化政策、そして銀行の預金準備要件の増加も要因の一つです。

1938年、米国は景気後退に対応して金融および財政政策を緩和しました。その年の2月に、ヘンリー・モージェントハウJr.財務長官は金不胎化政策を終了し、蓄積された金を減らし始めました - お金の印刷に似ています。しかし、政策決定者は、その行動はほとんど効果がないことを発見しました。1938年から1940年にかけて、マネーサプライの増加は銀行の準備金の総額を増加させたが、新金は主に現金準備金として保有され、実体経済への流入を妨げました。

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

政府はまた、20億ドルの財政刺激法案を可決しました。これには、WPAプログラムの大幅な増加が含まれていた(1938年に最大の年となった)。これらの措置は効果をもたらしましたが、最初ほどではありませんでした。鉱工業生産は1939年末までピークレベルまで回復せず、インフレ率は1940年末までゼロ付近であり、株式は1937年初めのレベルを約30%下回ったままでした。

米国における経済活動の最終的な回復は、主に第二次世界大戦によるものと思われます。アメリカが戦争に入る前は、同盟国に補給し、潜在的な戦争に備えるための生産と政府の支出が増加していました。その間、投資家がヨーロッパの政治情勢から安全な避難所を求め、連合軍がアメリカの物資を購入し始めた(1941年3月のLend-Leaseの制定以前)ため、金の流入が加速しました。

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

参考:It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

結局、第二次世界大戦によって、国家同士を統一し、そして調整されたそして非常に刺激的な財政および金融政策に関して政治的合意を作りました。1948年までFRBの議長を務めていたEcclesは、戦時中のその「主要な義務」を「軍事的要件および戦争目的の生産のための資金調達」としてまとめました。

第二次世界大戦中、政府の支出は大幅に増加し、マネーサプライは2倍以上に増えました。連邦準備制度理事会は、長期国債金利の上限を2.5%に、短期金利を0.375%に維持し、金利がこれらの水準に近づいたときに債券を購入することでマネタイズし政府支出をしました。

世界は1930年代には現在よりもグローバル化されていませんでしたが、当時の債務問題は依然としてグローバルで相互に関連していました。同様の問題が、日本とドイツにおいても起きました。詳しくはwww.economicprinciples.comをご覧ください。

このサイトはスパムを低減するために Akismet を使っています。コメントデータの処理方法の詳細はこちらをご覧ください。

ーーー

「金融政策3(MP3)」と「現代の通貨理論(MMT)」をもっと詳しく見る時が来た

2019年5月1日に公開されました

レイダリオ

ブリッジウォーターアソシエイツ、LPの共同最高責任者兼共同会長

1,250のように

コメント 139

シェア 225

この記事は、特に金融政策と財政政策が今後どのように異なるように機能するかについて、経済学に関心を持つ人々のためのものです。

それは、金融政策3(我々が世界中でもっと見るであろう新しいタイプ)と現代の通貨理論(かなりの注目を集めている最近提案された新しいアプローチ)に焦点を合わせるでしょう。

それは二つの部分からなる。

最初の部分はそのようなことを気にする人々にとって重要ですが、それは少し気まぐれであり、歴史的なケースを示す第2部分はとても気まぐれですので、あなたの興味に合ったどんな深さででもこれに入ってください。

パート1:MP3とMMTについて

私が経済と市場を見るとき、エンジニアが機械の因果関係を見るのと同じように、それらを機械的な方法で見ます。

私にとって、経済機械には、26文字のように、無限の数の組み合わせをもたらすことができる多数の方法でまとめることができる限られた数の基本的な因果関係( 「経済機械のしくみ」を参照)があります。アルファベットを組み合わせて無限の数の単語を作ることができます。

より具体的には、経済政策には、金融政策と財政政策の2つの基本的な構成要素があり、その下にはいくつかの方法(財政政策の課税と支出、および金融政策の金利と量的緩和と引き締め)があります。これらのうち、それらを設定することができる様々な方法があります。

全体像では、金融政策によってシステム内の総額とクレジット(つまり消費力)が決まり、財政政策によって、政府の出身地(税金)と行き先(つまり税金)への影響が決まります。支出)。

私にとって、世界中で最も重要な工学パズル政策決定者は、金融政策がうまくいかないときに、ほとんどの人にとって経済的な幸福を生み出すために経済的機械をどのように得るかということです。

金融政策がまったく機能しないわけではありません。

金利引き下げ(金融政策1と呼んでいます)や量的緩和(私が呼んでいるもの)を通じて、経済活動を刺激することに慣れ親しんだ方法では、経済的繁栄の刺激にはほとんど効果がありません。金融政策を呼び出す2)。

それは、お金と信用の成長(すなわち、支出力)を生み出すのに効果的ではなく、そして彼らの生産性と繁栄を高めることがほとんどの人々の手に渡るのに効果的ではないからです。

それゆえ、私達は金融政策3に行く必要があると思います。それは私達の人生の中で今まで見たことのない形式ですが、他の人生や遠く離れた場所には様々な形で存在しています。

金利が0%に固定されているときや量的緩和が目標を達成するのに効果的でないときに中央銀行家たちが緩和しようとすることは避けられないので、このシフトが起こるのは避けられない。

私は最近、過去の事例とそのような調整の将来の可能性についての私の以前の調査を刷新しました。それらを以下に共有します。

現代の貨幣理論は、私の考えでは避けられない正確な方法で見られるべきではない構成のそれらの無限の数のうちの1つです。

現代通貨理論が何であるかを知らないあなた方のために、それはここに記述されています( リンク)。

それは異なった人々によって異なって記述されているのでそれはわずかに異なった構成を持っています。

たとえば、学生のローンを撤廃するために使用される富税があるように財政政策を変更する人もいれば、他の方法で税金や支出を変更する人もいます。この段階では詳しく調べないでください。そうすることで、私たちは雑草や、重要なことを見る上で邪魔になるような詳細に私たちを駆り立てます。

また、パッケージとしてMMTに焦点を当てている人々は、最良のものを見つけるためにMP3ポリシーのより広い範囲について考えるのではなく、そのパッケージの詳細に彼らの考えを制限するでしょう。

MMTの最も重要な構成は、金利を0%に固定することであり、財政政策の黒字と赤字の変化を通じたインフレの厳格な管理があり、それが中央銀行が収益化する債務を生み出すことになります。

言い換えれば、私たちが慣れ親しんでいる間、金利は柔軟に動き、財政赤字(しばしば)と黒字(めったにない)は非常に粘着的だったので、金利は購買力とサイクルを生み出す上でより重要でした。利子率は0%で非常に粘着的になり、財政政策はより流動的かつ重要になり、赤字によって生み出された債務は貨幣化されるでしょう。

あなたが気づかなかった場合、それは概して起こっていることであり、ますます起こる必要があるでしょう。

言い換えれば、3つの主要準備通貨のうち2つ(ユーロと円)で金利が0%近くに固定され、3番目の最も重要な準備通貨(ドル)に固定される可能性が十分にあります。 )次の景気後退において。

その結果、収益化されている財政政策の赤字は、選択の現代的な刺激構成です。

MMTはそれを包含していますが、それは「近代通貨理論」と呼ばれる概念があるずっと前に存在しました。

ラベルを別にしても、1)金利を0%前後に固定する、2)債務の貨幣化を伴うより柔軟な財政政策、3)厳格なインフレターゲティングによる財政赤字の補填の構成が存在することが確かに事実である。準備通貨の国々では、必要、そして可能です。

このアプローチの付加的な利点は、中央銀行が金融資産を持っている人々から中央銀行から金融資産を購入して中央銀行から得たお金を使用するプロセスよりも、作成されたお金とクレジットの方が望ましい用途を満たすことができるということです。購入したい金融資産を購入します。

これが起こったことの歴史的な例はたくさんあります(ご存じのように、1930年代から1940年代の戦前と戦争の時代を見れば、似ていると思います)。

このアプローチの大きなリスクは、政治的に選出された政策決定者の手に資金、信用、そして支出を創出し、配分する力を与えることのリスクから生じます。

私の意見では、これらのMP3ポリシーをうまく機能させるためには、意思決定が賢明で政治的な動機のない、熟練した人々の手に渡るようにシステムを設計する必要があります。

それを達成するためのシステムの構築方法を想像するのは困難です。

同時に、私たちがこの方向に向かっているのは避けられません。

MP3とMMTについての私達の考えを見て

次のセクションでは、MP3がどのように見えるかについての私の考えのいくつかをより詳細に概説しますが、私と私のBridgewaterの同僚が真実であると信じる主なポイントは以下のとおりです。

我々は、財政政策は次の景気後退に十分な刺激を与えるために金融政策と結び付けられなければならないという考えに同意する。

これは、金融政策1(金利の移動に基づく)ではほとんどの場合単独では不可能であるか、またはほとんど不可能であることがほとんどであり、金融政策2(中央銀行の「印刷」および金融資産の購入に基づく)では刺激する。

「大きな債務危機を乗り越えるための原則」で説明されている理由から、各国の債務が自国通貨建てである限り、金融政策と財政政策の組み合わせが景気後退を円滑化するために役立つ可能性があります。経済政策立案者の能力が限られていることや、正しいことをする政治的能力が限られていることです。

私たちは財政と金融政策の調整を一種の金融政策3(MP3)として説明しました - そしてこれは金利引き下げ(MP1)とQE(MP2)が限られた有効性を持っているとき重要な政策ツールです。

金利の引き下げとQEは、他のところで詳細に説明した理由から、次の景気後退ではそれほど効果的ではないと思います。

我々はまた、金融政策が適切なトリクルダウンを生み出しているとは考えていません。

QEと金利の引き下げは、収益を上回っても下回るよりも多く得ます(これらは資産価格の引き上げを助け、すでに多くの資産を所有している人を助けます)。

そしてこれらのレバーは、教育、インフラストラクチャ、研究開発などの良い投資になるものにお金を向けることはしません。

明らかに、通常の財政政策は通常私たちがそのような種類の投資を扱う方法です。

しかし、景気後退時に財政政策に頼ることの問題は(それが非常に政治的に請求されていることを除けば)それは対応が遅いということです:それは長いリードタイムを持ち、プログラムを作らなければなりません。財政刺激策など

それが半自動スタビライザーであるかもしれないように金利が動くのと同じようにスイング方法で税金が動いているなら代わりに想像してみてください。

不況が発生した場合は、税金も自動的に引き下げられます。反対に、引き締めは税の上昇をもたらすでしょう。

企業や投資家にとって最も収益性の高い分野に金融市場を通過するのではなく、資金不足の分野(教育、インフラ、研究開発など)への投資収益率が高い半自動の投資増加を想像することができます。

中央銀行が印刷したお金でそのようなものに資金を供給するということは、中央銀行が赤字を貨幣化で賄うので、政府がより大きな借金の売上げをもたらし、より高い金利をもたらすという典型的な問題について心配する必要がないということです。 )

これまでに何度か説明し、2008年の金融危機以降に見てきたように、このような収益化によってインフレが大きくなりすぎることはありません。

それは、インフレは、支出の総量を販売された商品やサービスの量で割った値で決まるからです。

印刷されたお金が景気低迷の中で起こる信用と支出の減少の一部を単に相殺するのであれば、それはインフレを生み出さないでしょう。債務を大幅に金銭化した。

大きな問題は、これらのレバーをうまく引くために誰が信頼できるのかということです(中央銀行?連邦政府?)。

これらのツールは本当に善を成し遂げる力を持っていますが、責任を持って使われなければ、本当に害を及ぼすこともできます。

そのため、ガバナンスと決定権は慎重に設計する必要があります。

これは私がここでは説明しない大きなトピックです。

多くのMMT支持者が主張している一つの特定の政策は、保証付き雇用プログラムです。

それが実際にどのように行われるかに大きく依存します。

表面的なレベルでは、雇用の継続は一般的に人々の心理学/精神的健康、そして良い結果を生み出すために重要であるため、経済的不況で政府の仕事を通してお金を稼ぐために働く人々の考えが好きです。都市はきれいになり、互いに助け合っている。

私が同意しないMMTの側面があります。

ここにほんのカップルがあります:

私は、企業がコストに基づいて投資を行うのではなく、単に事業の見通しに基づいて意思決定を下すという考えには同意しません。

資金コストと事業見通しの両方が重要です。

資本コストは、物事を遂行する事業の決定に大きな影響を与えます。

たとえば、資本コストが低いことが、米国企業が大量の自社株買いを行った理由です。

MMTの中には、インフレを主に企業の過度な価格設定力のせいにする人もいます。

それがインフレに影響を与えるかもしれませんが、もっと大したのはあなたが何か(労働力、商品など)の不足とそれに対する過度の需要があるとき、そのことの価格は上がるということです。

金融政策3(MP3)はどのようなものか

私が述べたように、過去数回のサイクルで経済を刺激するのに十分であった政策ツールは、おそらく今度は十分ではないでしょう。

金融政策1(金利の引き下げ)は、先進国全体での非常に低い/マイナスの金利によって制限されています。

金融政策2(量的緩和)は、すでに非常に低い長期金利/資産の期待収益率と、現在の政治的制約を考慮して購入可能な債券が少なくなっている一部の中央銀行(特にECB)によって制限されています。

また、金融資産を持っていない人々にお金や信用を得ることは比較的効果的ではなく、機会格差の拡大にもつながります。

これらの理由から、私は次の不況では先進国は「金融政策3」(MP3)に目を向ける必要があると思います。

この研究では、1)MP3を定義し、2)その例を示し、3)1930年代に行われたことに焦点を当てます。

金融政策3は、投資家/貯蓄者(MP1とMP2が主に対象としているグループ)よりも浪費家に向けられている金融政策で構成されています。

言い換えれば、彼らはそれを使うように奨励金で浪費家に印刷されたお金を提供する政策です。

この種の政策は、間違いなく中央銀行と政府の双方にとって政治的に物議をかもしています。

大きな問題は、これらの政策が生産性を損なうか、あるいは助けるかどうかです。

「 大きな債務危機を乗り越えるための原則」という本で説明されている理由から、各国の債務が自国通貨建てである限り、これらの政策は経済の低迷を和らげるために役立つ可能性があります。生産された生産性が生産され費やされたお金と信用の量よりも多いならば、経済政策立案者および/または限られた政治的能力で正しいことをするためのものです。

だからこそ、政策立案者がこれらの政治的/その他の障害を乗り越えて「計画B」を策定することが重要である - MP1とMP2が十分な刺激を提供しない場合に彼らがすること財政プログラムなどに資金を提供する。

さもなければ、経済が落ち込んだときにこれらの政治的配慮をして取り組むことは不適切なリードタイムを提供するかもしれず、それは自己強化的な下向きの圧力を相殺するものが何もないので不況をはるかに悪化させる。

以下に、これらのMP3ポリシーがどのような形式をとることができるかについての私達の以前の研究のいくつかを共有し、最近のいくつかの例で更新します。

金融政策の定義3

私たちのほとんどは私たちの人生でそれを見ていませんが、それは他の人生や他の場所に存在していました。

MP3は、お金を受け取る人(民間部門と公共部門)、および印刷されたお金を直接提供する方法(消費者への間接的な資金調達手段に対する直接の「ヘリコプターお金」の提供)によって異なります。

次の図は、考えられる多くの種類のMP3をその連続体にマッピングしています。

一般的に、より直接的な政策はより効果的ですが、政治的にも困難です。

そして、最も直接的でない政策(あるいはそれらの変種)のいくつかが最近使われました、しかし次の重大な不況で必要とされるであろう規模ではありませんでした。

MP3はどのように見えますか

公共部門を対象とした MP3ポリシーから始めて、これらのポリシーをより詳しく(ポリシーが使用されたいくつかの歴史的事例を含めて)見ていきます。

最も直接的な選択肢は、新規発行の大部分を購入するQEと組み合わされた債務による財政支出の増加である (例えば、1930年代の日本、第二次世界大戦中の米国、そして2008年の金融危機後のほぼすべての大先進国)。

中央銀行は、刺激関連のプロジェクトに資金を使用する開発銀行またはその他の民間/半民間企業に貸付/資本化することができます(たとえば、2008年の中国)。

最後に、中央銀行が政府のプログラムを収益化することを明確に目的としている場合には、 直接的な財政的/金銭的調整があり得る。

これは次のようにして発生する可能性があります。

財務省が借金に追いついていない、借金による財政支出の増加。

支出は、中央銀行が債務を回収するか、または債務を永遠に延期することを約束するQEとペアになります。

中央銀行は借金の支払いをカバーするためにお金を印刷することを約束している(例えば1930年代のドイツ)、または

借金の発行を煩わさずに、印刷したばかりのお金を直接政府に渡します。

過去の事例には、平凡通貨の印刷(例:帝国中国、アメリカ独立戦争、1930年代のアメリカ南北戦争、ドイツ、第一次世界大戦中のイギリス)、または硬貨通貨の引き下げ(古代ローマ、中国帝国、16世紀イギリス)が含まれています。

これらのMP3ポリシーは、民間部門と公共部門の両方での支出をサポートしています 。

以下は洗濯物リストの例です。

明確にするために、私達はこれらのどれも推奨していません。

具体的な例を挙げています。

QEは不動産や他の実物を購入するのに使われるかもしれません 、そしてそれは理想的に社会的に有益な目的のために使われるでしょう。

たとえば、デトロイトで放棄された土地を購入し(個人の土地所有者をサポートする)、公園を建設するためにそれらを破壊します。

多額の資金創出を伴う多額の負債評価減(「ジュビリー年」)

この直接的ではないバージョンは、長期にわたって債務の実際の価値を下げるために、より高いインフレまたは通貨切り下げを明示的に目標とすることによるものです。

レバーとして通貨介入/減価償却を明示的に使用する中央銀行はこれを助けるでしょう。

例えば、大恐慌の間のドル切り下げ(金連動債務を無効にする法律とペアになった)は、事実上、大きな債務償却を生み出しました。

場合によっては、政府が債務の評価減を直接作成または交渉した(例えば、古代ローマ、大恐慌、アイスランドなど)。

これらのMP3ポリシーは民間部門を対象としています 。

MP3政策は銀行を通じて機能する可能性があり、貸付に対する非常に強いインセンティブを提供します。

例えば、余剰準備金に対するマイナスの利子率に加えて、中央銀行は、必要な準備金に対して非常にプラスの利子率を提供することができます。

このプログラムのフレーバーは、最近ヨーロッパ、日本、そしてイギリスで試みられました。

これを達成するための別の方法は、補助金を受けたローンまたは保証を通して借りるように世帯を動機付けることです。

その一例が英国の「購入支援」プログラムで、一部の住宅購入者に不動産価値の最大20%までの5年間の無利子融資を提供しています。

これまでのところ、否定的な率は世帯にあまり流れていない。

中央銀行は、 世帯が現金を保有するのを妨げて世帯に支出を促すことを明確に目的とした実験を行うことができます。

例えば、何人かの人々は、負の利子率と同じ利子率で現金を保有することに対する「帳簿税」を提案している(これはヨーロッパで大恐慌の間に実験された)。

他の人々は物理的なお金を無効にして、すべての現金保有物に負の金利を適用することをより簡単にするためだけにデジタルお金を使うことを提案しました。明らかにこれは極端でしょう。

中央銀行は、おそらくバンド内で、 所得税率や売上税率の変更を管理できます。

それから彼らはそれを経済を管理するための追加的な反循環的なレバーとして使い、不況時の税金を引き下げ(マネープリントとペアにする)、そして適時に税金を引き上げることができます。

お金を印刷し、世帯に直接現金で送金する(すなわち、ヘリコプターのお金)。

私たちがヘリコプターのお金に言及するとき、それは彼らが使うためにお金の浪費家の手の中にお金を向けることを意味します(例えば、大恐慌の間のアメリカの退役軍人のボーナス、帝国中国)。

基本的な変種は、a)全員に同じ金額を指示するか、または1つ以上のグループを他のグループよりもある程度手助けすることを目的とする(たとえば、裕福な人々よりも貧しい人々に)のいずれかです。そして、b)このお金を一時的なものとして、または時間をかけて(おそらく普遍的な基本収入として)提供すること。

これらの変種は、1年以内に使われなければお金が消えるように、それを使う動機と対になることがあります。

お金は、社会的に望ましい支出/投資に向けてそれをターゲットにするために、特定の投資口座(退職、教育、または中小企業投資のために割り当てられた口座のような)に向けられるかもしれません。

政策を策定するための1つの可能性のある方法は、QEからの返品/保有を政府ではなく世帯に分配することです。

ヘリコプターマネーの変種として、中央銀行は資産価格をさらに引き上げ支出を支援するために、ドローダウン保護を与えたり、株式やリスクの高い資産の収益率を保証することができます。

繰り返しになりますが、これらの相対的なメリットについては何もコメントしておりません。

政策決定者の立場にあれば、私たちは覗き込んでいるだろうという過去の事例の範囲と数についての感覚をあなたに与えているだけです。

次に、この審査プロセスでは、各国で何が合法であり、何が政治的に許容できるのかを検討する必要があります。

最善の結果を出すのは大変な仕事ですから、時間がかかります。

その結果、政策立案者、特に中央銀行は、今、これを解決するために一生懸命取り組む必要があると考えています。

私たちはこれらのそれぞれについて意見を述べることはしませんが、最も効果的なアプローチは財政と通貨の調整であるという意見を提供します。

中央銀行が人々にお金(ヘリコプターのお金)を与えるだけでは、お金を使うインセンティブを持って彼らにお金を与えるよりも一般的には不十分です。しかし、時々、金融政策を設定する人々が財政政策を設定する人々と調整することが困難である場合、他のアプローチが使用されます。

これらのケースを見るとき、それらがそれらの2つ以上の要素を持っていて、それらが上で言及された連続体に存在するので時々方針がこれらのカテゴリーに正確には入らないことを覚えておいてください。

MP2(QE)とMP3の間に明確な境界線さえありません。

たとえば、政府が減税を与える場合、それはおそらくヘリコプターのお金ではありませんが、それはそれがどのように資金を供給されたかに依存します。

政府が浪費家として行動し、中央銀行が資金を借りずにその支出に資金を供給することができます - それは財政の経路を通じたヘリコプターのお金です。

パート2:歴史的事例

あまり効果的ではないMP1とMP2の多くの歴史的事例があり、私はあなたにMP3に関する歴史的事例の束を示したいと思いますので、深く掘り下げることなく過去の状況を知ることができます。そのためには、私たちがあなたにそれらの大本を渡しなければならないからです。

私がやろうとしているやり方は、当時の世界大恐慌の間に最初に金融政策3を掘り下げてから、表面的にいくつかの他のケースを見てみることです。ポリシー。

私があなたに示すことは長くて興味深いです、そしてそれは私達が信じられないと考えるであろういくつかの事柄がいかに必要から生じたかを含みます。

そのようなことを伝えることで、私たち全員があなたの考えをあなたが通常想像するよりも広い範囲の可能性に広げることができるようになることを私は願っています。

この資料のすべてはかなり長くて不愉快なので、興味のある方のためにwww.economicprinciples.orgに投稿しました。

しかし、世界的な大恐慌で起こったことは、今日の環境に類似した最も最近の事件であるので、私があなたがただ一つの象徴的な事件を検討したいならば、私はそれを下記に含みます。

付録:金融政策の詳細な歴史的事例3

私たちは今、あなたに多数の例を示すつもりです、いくつかは他より深く説明されました。

それらはすべて、今検討したばかりのMP3に関する原則を例示しています。

多すぎることがわかったら、あとはスキップしてください。

事例1:1930年代のアメリカで

すでに述べたように、フランクリンD.ルーズベルト大統領の政策、特に1933年の金とドルの切り下げは、「美しいレバレッジ解消」を生み出しました。不況。

実際、その年の「文字列を押す」という言葉は、FRB議長のMarriner Ecclesに疑問を投げかける米国の代表によって造られました。

このセクションでは、米国がどのようにしてMP1とMP2(低金利とお金の増加)を調整された創造的な財政政策で補完し、1937年の不況から抜け出すために財政と金融の調整に頼ったかについて述べる。

ルーズベルトが最初に行った大きな財政政策の転換の1つは、彼の「美しいレバレッジ解消」の一環として、巨額の負債評価減を処理することでした。彼はそれをいくつかの異なる方針で行った。

第一に、米国は債務契約から「金条項」を排除する法律を可決した。

それまでは、ほとんどの長期借入金に金の指数表示条項がありましたが、これは切り下げによって名目上の債務負担が大幅に増加することを意味していました。

その条項を廃止することで、ドルが下落しても債務負担が同じになり、事実上、広範囲にわたる債務再編が生まれました。

もちろん、それは政府が債権者を犠牲にして債務者に利益をもたらすような方法で契約を破ることを法律で制定したことを意味しました。

この事件は最高裁判所に持ち込まれ、政府の賛成で5-4を決定した。

第二に、1933年にルーズベルトは水中住宅ローンの借り手を支援する機関、住宅所有者ローン公社(HOLC)を設立しました。

この機関は、抵当貸付を政府保証付き債券と交換し、抵当権実行額を上回る抵当を購入し、貸し手の参加を促しました。

その後、HOLCは住宅ローンを再構築し、金利を引き下げ、ローン期間を15年まで延長します(住宅ローンの期間は通常5年から10年です)。

場合によっては(通常ではありませんが)、HOLCは元本を減らして、借り手のローン対価値(LTV)の比率を80%未満に保つこともあります。

この機関は、全住宅ローンの約20%を占める100万件のローンを47億5000万ドル(GDPの約8%)を使って購入しました。

ルーズベルトはまた、 人々を直接雇用する大規模な政府プログラムも作成しました。

最も重要なものは1935年に始まったWorks Progress Administration(WPA)でした。それは第二次世界大戦の始まりまで続き、年間GDPのおよそ2%に等しい支出を表しました。

WPAは、すべてのプロジェクトが人件費の少なくとも90%を費やすことを義務付けているため、特に雇用に焦点を当てていました。

ホワイトカラーや芸術作品のための資金もありましたが、ほとんどのプロジェクトはインフラ関連でした。プログラムは図書館員、音楽家、作家、仕立て屋、教師、研究者、医師、建築家などを雇いました。

ピーク時には、労働人口の6%を超える約350万人が雇用されていました。

1936年に更なる刺激があり、早期退役軍人のボーナスが大金になった。

このプログラムは、世帯に直接現金で送金するための政府借入の特に良い例です。

政府が文字通りしたことは、即時の支払いと交換するか、または満期まで保有することができ、市場を上回る割引率を支払うことで、退役軍人に市場性のない債券を提供することでした。

また、以前に彼らの将来のボーナス支払いに対して政府から借りていた退役軍人は利子赦しを受けた。

債券の80%が1936年に現金化され、平均受取人は当時の個人平均年収を上回る約500ドルを受け取った。

全体として、このプログラムは名目GDPの約2%に相当する財政刺激策を表しています。

ボーナス受領者は、ボーナスを使う傾向が高く、住宅投資や自動車購入のように、クレジットで購入した場合の頭金の支払いによく使用されていました。

この期間を通じて、米国は財政的インセンティブとマクロプルーデンス緩和を利用して信用と支出を刺激する他の多くのプログラムを展開しました 。これらのプログラムは、既存の借り手を支援し、住宅投資のための新たな融資を奨励しました。

1932年、連邦議会は準中央銀行として機能し、S&L銀行に資金を提供し、引受基準および担保制限を設定するために連邦住宅ローン銀行制度を創設しました。

1933年、住宅所有者ローン法は、20,000ドル以下の住宅で住宅ローンを借り換えることを連邦政府に保証していました。

1934年に、連邦準備制度理事会は、株式を購入するための証拠金要件(規制T)を設定する能力を与えられました。

それはニューヨーク証券取引所によって最近導入された規則とほぼ同じレベルで、45%の「非常に緩やかな」証拠金要件(後の連邦準備制度の報告によると)から始まった。

1934年に議会は、住宅ローンを保証するために連邦住宅管理局(FHA)を設立しました。これにより、民間市場が提供していたものよりも保険適格ローンの引受基準(80%LTVおよび20年満期)が容易になりました。

1つのFHAプログラムは、5年の満期までの住宅資産を改善するためのローンの20%を保証しました。

1934年に、ルーズベルトは36ヶ月までの間家電製品に安いローンを提供するために家の家と農場当局を設立しました(10%の金利、5%の頭金)。

1935年、議会は国内銀行のLTVと満期の制限を緩和しました(これまでは最大5年のローンと50%のLTV、現在は10年と60%のLTVのみ)。

1937年、連邦準備制度理事会は、景気後退を受けて、自己資本比率の要件を40%に引き下げました(1936年に引き上げられました)。

ルーズベルトの財政支出プログラムは、支出削減(ルーズベルト大統領の初期の段階で軍を削減した)と赤字支出の組み合わせによって賄われていた。この赤字支出は主に直接QEによって賄われていません。

米国の切り下げに続く持続的な金の流入はマネーサプライを増加させました。民間部門への貸付を増やすことを望まない銀行は、政府支出に資金を供給しながらほぼ保証されたスプレッドを作るために政府債務の保有を大幅に増加させました。

1937 - 38年の景気後退に対する政府の対応

1937年、米国は50%以上の下落、成長はマイナスに転じ、米国はデフレに転落しました。

これまでに説明したように、この低迷の原因については説明しませんが、WPA雇用プログラムの縮小と1936年の退役軍人ボーナスの減退効果が、フランスとイタリアでのドル切り下げとともに大きな貢献をしました。感謝、金の流入の消毒、そして銀行の預金準備要件の増加。

1938年、米国は景気後退に対応して金融および財政政策を緩和しました。その年の2月に、ヘンリー・モージェントハウJr.財務長官は金の滅菌プログラムを終了し、蓄積された滅菌された金を消毒し始めました - お金の印刷に似ています。

しかし、政策決定者は、彼らの行動はほとんど効果がないことを発見しました。

1938年から1940年にかけて、マネーサプライの増加は銀行の準備金の総額を増加させたが、新金は主に現金準備金として保有され、実体経済への流入を妨げた。

政府はまた、20億ドルの財政刺激法案を可決した。これには、WPAプログラムの大幅な増加が含まれていた(1938年に最大の年となった)。

これらの措置が何らかの効果をもたらした間、経済の最初の改善は弱まりました。鉱工業生産は1939年末までピークレベルまで回復せず、インフレ率は1940年末までゼロ付近で回復し、株式は1937年初めのレベルを約30%下回ったままでした。

米国における経済活動の最終的な回復は、主に第二次世界大戦によるものと思われます。

アメリカが戦争に入る前は、同盟国に補給し、潜在的な戦争に備えるために、生産と政府の支出が増加していました。

その間、投資家がヨーロッパの政治情勢から安全な避難所を求め、連合軍がアメリカの物資を購入し始めた(1941年3月のLend-Leaseの制定以前)ため、金の流入が加速しました。

結局、第二次世界大戦の共通の原因は国を団結させて、 調整されたそして非常に刺激的な財政と金融政策の政策についての政治的合意を作成しました。

1948年までFRBの議長を務めていたEcclesは、戦時中のその「主要な義務」を「軍事的要件および戦争目的の生産のための資金調達」としてまとめた。第二次世界大戦中、政府の支出は大幅に増加し、マネーサプライは2倍以上に増えました。

連邦準備制度理事会は、長期国債金利の上限を2.5%に、短期金利を0.375%に維持し、金利がこれらの水準に近づいたときに債券を購入することで、政府支出を収益化しました。

世界は1930年代には現在よりもグローバル化されていませんでしたが、当時の債務問題は依然としてグローバルで相互に関連していました。

私たちはあなたに多くの国で同様の発展を示すことができました、しかし、簡潔さのために、日本とドイツで起こったことだけに触れます。

同様のことが他の多くの国でも起こりました。

より歴史的な例については、www.economicprinciples.comをご覧ください。

レイダリオ

ブリッジウォーターアソシエイツ、LPの共同最高責任者兼共同会長

た

139コメント

article-comment__ゲスト画像

コメントを残すにはログインしてください

もっとコメントを見る

Ray Dalioによるその他のアイテム

95記事

細分化された個別の意思決定から調整された集団的な意思決定への進化

細分化された個々の決定から進化する…

2019年4月22日

なぜ、そしてどのようにして資本主義を改革する必要があるのか(その1と2)

なぜそしてどのようにして資本主義を改革する必要があるのか…

It’s Time to Look More Carefully at “Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)” and “Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)”

This article is for folks who are interested in economics, especially about how monetary and fiscal policy will work differently in the future. It will focus on Monetary Policy 3 (the new type that we will see more of around the world) and Modern Monetary Theory (a recently proposed new approach that has received a fair amount of attention). It comes in two parts. The first part is important for folks who care about such stuff but it’s a bit wonky and the second which shows historical cases is very wonky so feel free to wade into this in whatever depth suits your interest.

Part 1: Understanding MP3 and MMT

When I look at economies and markets I look at them in a mechanical way much like an engineer would look at cause-effect relationships of a machine. To me the economic machine has a limited number of basic cause-effect relationships (see “How the Economic Machine Works”[https://www.economicprinciples.org/downloads/bw-populism-the-phenomenon.pdf]) that can be put together in numerous ways that can lead to an infinite number of combinations, just like the 26 letters of the alphabet can be combined to make up an infinite number of words. More specifically there are two basic building blocks of economic policy, which are monetary and fiscal policy, and under these there are a few ways (taxing and spending for fiscal policy, and interest rates and quantitative easing and tightening for monetary policy) and under each of these there are various ways they can be configured. At the big picture level, monetary policy determines the total amount of money and credit (i.e., spending power) in the system, and fiscal policy determines the government’s influence on where it’s taken from (i.e., taxes) and where it goes (i.e., spending).

To me the most important engineering puzzle policy makers around the world have to solve for the years ahead is how to get the economic machine to produce economic well-being for most people when monetary policy does not work. I don’t mean that monetary policy won’t work at all; I mean that it won’t work hardly at all in stimulating economic prosperity in the ways that we are used to having it stimulate economic activity, which are through interest rate cuts (what I call Monetary Policy 1) and through quantitative easing (what I call Monetary Policy 2). That is because it won’t be effective in producing money and credit growth (i.e., spending power) and it won’t be effective in getting it in the hands of most people to increase their productivity and prosperity. Hence I believe we will have to go to Monetary Policy 3, which is fiscal and monetary policy coordination that is of a form that we haven’t seen before in our lifetimes but has existed in various forms in others’ lifetimes or faraway places. It is inevitable that this shift will happen because it is inevitable that central bankers will want to ease when interest rates are pinned at 0% and when quantitative easing will be ineffective in achieving the goal. I recently refreshed my prior exploration of past cases and future possibilities of such coordination, which I will share below.

Modern Monetary Theory is one of those infinite number of configurations that is in my opinion inevitable and shouldn’t be looked at in a precise way. For those of you who don’t know what Modern Monetary Theory is, it’s described here (link[https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_Monetary_Theory]). It’s described differently by different folks so it has slightly different configurations. For example, some might change fiscal policy so that there is a wealth tax that is used to eliminate student loans, and others might change taxes and spending in other ways, and there are an infinite number of ways these changes can be configured that we shouldn’t delve into at this stage because that will drive us into the weeds and the particulars that will stand in the way of seeing the big important things. Also, people who are focusing on MMT as a package will limit their thinking to the specifics of that package rather than thinking about the wider range of MP3 policies to find the best one.

MMT’s most important configuration is the fixing of interest rates at 0% and there is the strict controlling of inflation via the changing of fiscal policy surpluses and deficits, which will produce debt that central banks will monetize. In other words, whereas during the times we have become used to, interest rates moved around flexibly and fiscal deficits (often) and surpluses (rarely) were very sticky so interest rates were more important in producing buying power and the cycles, in the future interest rates will be very sticky at 0% and fiscal policies will be much more fluid and important and the debts produced by the deficits will be monetized. In case you didn’t notice, that is by and large what has been happening and will increasingly need to happen. In other words, interest rates are now pinned near 0% in two of the three major reserve currencies (the euro and the yen) and there is a good chance that they will be pinned there in the third and most important reserve currency (the dollar) in the next economic downturn. As a result, fiscal policy deficits that are monetized is the contemporary stimulation configuration of choice. That existed long before there was a concept called “Modern Monetary Theory,” though MMT embraces it. Putting labels aside, it is certainly the case that the configuration of having 1) an interest rate fixed at around 0%, 2) more flexible fiscal policies with debt monetization to fund the resulting deficits with 3) rigorous inflation targeting exists and is increasingly likely, necessary, and possible in reserve currency countries. An added benefit of this approach is that the money and credit created can be better targeted to fund the desired uses than the process of having the central bank buy financial assets from those who have financial assets and use the money they get from the central bank to buy the financial assets they want to buy. There are many historical cases of this happening (see the 1930s-1940s prewar and war periods which, as you know, I think are analogous), which offer worthwhile lessons about how this was and could be engineered.

The big risk of this approach arises from the risks of putting the power to create and allocate money, credit, and spending in the hands of politically elected policy makers. In my opinion, for these MP3 policies to work well, the system would have to be engineered in a way that decision making would be in the hands of wise, not politically motivated, and highly skilled people. It’s difficult to imagine how the system will be built to achieve that. At the same time it is inevitable that we are headed in this direction.

Looking at Our Thinking about MP3 and MMT

In the following section, I will outline some of my thoughts on what MP3 is likely to look like in more detail, but the main points me and my Bridgewater colleagues believe to be true are:

- We agree with the notion that fiscal policy has to be connected with monetary policy to provide enough stimulus in the next economic downturn. That is because Monetary Policy 1 (based on moving interest rates) is in most cases either unable to happen alone or unable to happen much, and Monetary Policy 2 (based on central banks “printing money” and buying financial assets) has limited power to stimulate. For reasons explained in “Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises,” as long as countries have their debts denominated in their own currencies, the combination of monetary and fiscal policies would likely work to smooth out economic downturns, and the only things that stand in the way are the limited capabilities of economic policy makers and/or the limited political abilities to do the right things.

- We’ve described the coordination of fiscal and monetary policy as a type of Monetary Policy 3 (MP3)—and this is a critical policy tool when interest rate cuts (MP1) and QE (MP2) have limited effectiveness.

- We think that interest rate cuts and QE will be significantly less effective in the next downturn for reasons we’ve described in depth elsewhere. We also don’t believe that monetary policy is producing adequate trickle-down. QE and interest rate cuts help the top earners more than the bottom (because they help drive up asset prices, helping those who already own a lot of assets). And those levers don’t target the money to the things that would be good investments like education, infrastructure, and R&D.

- Obviously, normal fiscal policy is usually the way we handle those sorts of investments. But the problem with relying on fiscal policies in a downturn (besides them being highly politically charged) is that it is slow to respond: it has long lead times, you have to make programs, concerns over deficits can make it more challenging politically to pass fiscal stimulus, etc.

- Imagine instead if you had taxes operating in a swing way, the same way that interest rates move, so that it could be a semi-automatic stabilizer. If you had a recession you would have the equivalent automatic reduction in taxes. On the opposite end, a tightening would result in a rise in taxes.

- We could imagine semi-automatic increases in investments with high ROI to underfunded areas (e.g., education, infrastructure, R&D) rather than just going through financial markets to the areas that companies and investors find most profitable for them.

- Funding such things with money printed by the central bank means that the government doesn’t have to worry about the classic problem of the larger deficits leading to more debt sales leading to higher interest rates because the central bank will fund the deficits with monetization (QE). As we’ve described several times before and have seen since the 2008 financial crisis, such monetization won’t cause too much inflation. That is because inflation is determined by the total amount of spending divided by the quantity of goods and services sold. If the printed money simply offsets some of the decline in credit and spending that happens in an economic downturn, then it won’t produce inflation, e.g., over the last decade central banks struggled with inflation being too low, not runaway inflation, while they have massively monetized debt.

- The big question is who can be relied on to pull these levers well (central bank? federal government?). These tools have the power to do real good but they also can do real harm if not used responsibly. So the governance and decision rights would need to be carefully engineered. That’s a big topic I won’t get into here.

- One specific policy that many MMT proponents have advocated for is a guaranteed jobs program. A lot depends on how that would actually be done. At a superficial level, I like the idea of people working to earn money through a government job in an economic downturn versus just getting welfare checks because staying employed is generally important for people’s psychology/emotional health as well as producing good outcomes (like keeping our cities clean and helping each other).

- There are aspects of MMT that I disagree with. Here are just a couple:

- I disagree with the notion that businesses don’t make investments based on the cost of money and just make decisions based on business prospects. Both the cost of funds and business prospects are important. The cost of capital is a giant influence on the decisions of businesses to do things. For example, the low cost of capital was the reason US companies did huge amounts of share buybacks.

- Some MMTers blame inflation primarily on businesses’ excessive pricing power. While that might influence inflation, the bigger deal is that when you have a shortage of something (labor, commodities, etc.) and excessive demand for it, the price of that thing goes up.

What Monetary Policy 3 (MP3) Could Look Like

As I’ve noted, the policy tools that were sufficient to stimulate the economy in the last several cycles probably won’t be enough this time around. Monetary Policy 1—cutting interest rates—is limited by very low/negative rates across the developed world that probably can’t be lowered all that much more. Monetary Policy 2—quantitative easing—is limited by already very low longer-term interest rates/expected returns on assets and some central banks (especially the ECB) running low on bonds they can buy given current political constraints. Also, it is relatively ineffective in getting money and credit to those who don’t have financial assets, and it contributes to the widening opportunity gap. For these reasons, I believe in the next downturn developed countries will need to turn to “Monetary Policy 3” (MP3). In this study we will 1) define MP3, 2) give examples of it, and 3) focus on what was done in the 1930s.

Monetary Policy 3 comprises monetary policies that are more directed at spenders than at investors/savers (the groups that MP1 and MP2 principally target). In other words, they are policies that provide printed money to spenders with incentives for them to spend it. These sorts of policies will undoubtedly be politically controversial for both central banks and governments. The big question is whether these policies will hurt or help productivity. For reasons explained in the book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, as long as countries have their debts denominated in their own currencies, these policies would likely work to smooth out economic downturns, and the only things that stand in the way are the limited capabilities of economic policy makers and/or the limited political abilities to do the right things, if the productivity produced is more than the amount of money and credit that is produced and spent. That’s why it’s important for policy makers to work through these political/other impediments and develop their “Plan B” now—what they’ll do when MP1 and MP2 don’t provide enough stimulus (e.g., buy equities, buy lesser quality debt, fund fiscal programs, etc.). Otherwise, working through those political considerations as the economy turns down might provide inadequate lead time, which can make the downturn much worse because there is nothing to offset the self-reinforcing downward pressures.

Below, I’ll share some of our prior research on what sort of forms these MP3 policies can take, updated with some recent examples.

Definition of Monetary Policy 3

Though most of us haven’t seen it in our lifetimes, it has existed in other lifetimes and other places. MP3 is a continuum of coordinated monetary and fiscal policies that vary who gets the money (private sector versus public sector) and how directly that printed money is provided (directly providing “helicopter money” to spenders versus more indirect means of financing spending). The following diagram maps many of the possible types of MP3 onto that continuum. In general, the more direct policies would be more effective, but also more politically difficult to do. And some of the least direct policies (or variants of them) have recently been used, but not at the scale that would likely be needed in the next significant downturn.

What MP3 Looks Like

We’ll walk through those policies in more detail (including some historical cases in which the policies were used), starting with MP3 policies that are targeted to the public sector:

- The least direct option is an increase in debt-financed fiscal spending, paired with QE that buys most of the new issuance (e.g., Japan in the 1930s, the US during WWII, and nearly every large developed country following the 2008 financial crisis).

- Central banks could lend to/capitalize development banks or other private/semi-private entities that would use the financing for stimulus-related projects (e.g., China in 2008).

- Finally, there can be direct fiscal/monetary coordination, where the central bank explicitly aims to monetize government programs. This could occur via:

- An increase in debt-financed fiscal spending, where the Treasury isn’t on the hook for the debt because:

- The spending is paired with QE where the central bank retires the debt or commits to rolling the debt forever,

- The central bank promises to print money to cover debt payments (e.g., Germany in the 1930s), or

- Directly giving newly printed money to the government to spend, not bothering to go through issuing debt. Past cases have included printing fiat currency (e.g., Imperial China, the American Revolution, the US Civil War, Germany in the 1930s, the UK during WWI) or debasing hard currency (Ancient Rome, Imperial China, 16th century England).

These MP3 policies support spending in both the private and public sectors. What follows is a laundry list of examples. To be clear, we aren’t recommending any of these; we are just giving you tangible examples.

- QE could be used to purchase real estate or other real goods, which would then ideally be used for socially beneficial ends. For instance, buying up abandoned properties in Detroit (which would support private landholders) and demolishing them to build parks.

- Big debt write-down accompanied by big money creation (the “year of Jubilee”)

- The less direct version of this is via explicitly targeting higher inflation or currency devaluation to lower the real value of the debt over time.

- Central banks explicitly using currency intervention/depreciation as a lever would help with this. For instance, the dollar devaluation during the Great Depression (paired with a law invalidating gold-linked debt) effectively produced a big debt write-off.

- In certain cases, governments directly created or negotiated debt write-downs (e.g., Ancient Rome, Great Depression, Iceland recently).

These MP3 policies are targeted toward the private sector:

- MP3 policies could work through banks, providing them very strong incentives to lend. For instance, in addition to negative rates on excess reserves, the central bank could offer highly positive rates on required reserves—making it materially more profitable for banks to lend(versus building up excess reserves as central banks print money). Flavors of this program have recently been attempted in Europe, Japan, and the UK.

- A different way of accomplishing this is incentivizing households to borrow through subsidized loans or guarantees. One example is the UK’s “Help to Buy” program, providing a five-year, interest-free loan for up to 20% of the property value to some home buyers.

- So far, negative rates haven’t flowed through to households much. Central banks could experiment with explicitly aiming to disincentivize households from holding cash to induce households to spend. For instance, some people have suggested a “carrying tax” on holding cash, at the same rate as the negative interest rate (this was experimented with in Europe during the Great Depression). Other people have suggested invalidating physical money and using digital money only to make it easier to apply a negative interest rate to all cash holdings. Obviously this would be extreme.

- Central banks could be given control over changing income tax rates or sales tax rates, perhaps within a band. They could then use it as an additional countercyclical lever to manage the economy, lowering taxes in recessions (pairing it with money printing) and raising taxes in good times.

- Printing money and doing direct cash transfers to households (i.e., helicopter money). When we refer to helicopter money, we mean directing money into the hands of spenders of money to get them to spend (e.g., US veterans’ bonus during the Great Depression, Imperial China).

- How that money is directed could take different forms—the basic variants are a) to either direct the same amounts to everyone or to aim for some degree of helping one or more groups over others (e.g., to the poorer more than to the rich), and b) to provide this money either as one-offs or over time (perhaps as a universal basic income). These variants could be paired with an incentive to spend it—like the money disappearing if not spent within a year.

- The money could be directed to specific investment accounts (like retirement, education, or accounts earmarked for small business investments) to target it toward socially desirable spending/investment.

- One potential way to craft the policy is to distribute returns/holdings from QE to households instead of to the government.

- As a variant of helicopter money, central banks could give drawdown protection or guarantee a rate of return for stocks and riskier assets in order to further increase asset prices and support spending.

To reiterate, we aren’t offering any comments on the relative merits of these; we are just giving you a sense of the range and the number of historical cases that, if we were in the position of policy makers, we would be looking through. This examination process then has to consider what’s legal, and what’s politically acceptable, in each country. It’s a big job to work out what’s best, so that will take time. As a result, we believe that policy makers, especially central bankers, need to work hard on figuring this out now.

While we won’t offer opinions on each of these, we will offer our opinion that the most effective approach is fiscal/monetary coordination, because it assures that both the providing of money and the spending of it will occur. If central banks just give people money (helicopter money), that’s typically less adequate than giving them that money with incentives to spend the money. However, sometimes it is difficult for those who set monetary policy to coordinate with those who set fiscal policy, in which case other approaches are used.

As we look at these cases, keep in mind that sometimes the policies don’t fall exactly into these categories, as they have elements of more than one of them and they exist on the continuum mentioned above. There is not even a clear line of demarcation between MP2 (i.e., QE) and MP3. For example, if the government gives a tax break, that’s probably not helicopter money, but it depends on how it’s financed. There can be the government acting as the spender, with the central bank financing that spending without a loan—which is helicopter money through fiscal channels.

Part 2: Historical Cases

There are many historical cases of less effective MP1 and MP2 leading to cases of directing monetary policy to put I’d like to show you a bunch of historical cases on MP3 so you get a flavor of how they worked in the past without delving deeply into each because we would have to give you a big book of them to do that. The way I am going to do that is to first dig into Monetary Policy 3 during the Great Depression in the major economies at the time, and then superficially look at several other cases, including some QE cases that are beginning to cross the line to MP3 policies. What I will show you is long but interesting, and it includes how some things that we would consider implausible came about out of necessity. My hope is that in conveying such things we will all be able to open your thinking to a wider range of possibilities than you ordinarily might imagine. Because all of this material is rather long and wonky, I’ve posted it at www.economicprinciples.org for those of you who are interested. But since what happened in the global great depression is the most recent analogous case to today’s environment, I’m including that below if you’d like to examine just one iconic case.

Appendix: Detailed Historical Examples of Monetary Policy 3

We are now going to show you a large number of examples, some explained in more depth than others. They all exemplify the principles about MP3 that we just reviewed. If you find that there are too many, just skip the rest.

Example 1: In the US during the 1930s

As we’ve previously described, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policies—especially devaluing the dollar versus gold in 1933—helped create a “beautiful deleveraging.” But by 1935, policy makers were already expressing concern about how the US might offset the next economic downturn. In fact, that year the term “pushing on a string” was coined by a US representative questioning Fed Chair Marriner Eccles, who was concerned that the Fed could stop an expansion but couldn’t do much to offset a contraction. In this section, we describe how the US complemented MP1 and MP2 (low rates and an increase in money) with coordinated, creative fiscal policy—and relied on fiscal and monetary coordination to pull out of the 1937 downturn.

One of Roosevelt’s first major fiscal policy shifts was to engineer big debt write-downs as part of his “beautiful deleveraging” mix. He did that through a couple different policies. First, the US passed a law eliminating the “gold clause” from debt contracts. Up until then, most long-term debts had gold indexation clauses that would have meant the devaluation would increase nominal debt burdens significantly. Eliminating that clause kept debt burdens the same even as the dollar fell, effectively creating a broad-based debt restructuring. Of course, that meant that the government legislated the breaking of contracts in a way that benefited debtors at the expense of creditors. This case was taken to the Supreme Court and decided 5-4 in the government’s favor.

Second, in 1933 Roosevelt created an agency to aid underwater mortgage borrowers, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). This agency exchanged distressed mortgages for government-guaranteed bonds, purchasing the mortgages above foreclosure value, which encouraged lender participation. Then the HOLC would restructure the mortgages, lowering the interest rate and extending the term of the loan to 15 years (mortgages then typically had a 5- to 10-year maturity). In some cases (though not typically), the HOLC would also reduce the principal to keep the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio for borrowers below 80%. The agency purchased 1 million loans, about 20% of all mortgages, spending $4.75 billion (approximately 8% of GDP).

Roosevelt also created large government programs that directly employed people. The most significant was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), started in 1935. It lasted until the start of World War II and represented spending equal to approximately 2% of GDP annually. The WPA was focused specifically on employment, as it mandated that all projects spend at least 90% of costs on labor. Most projects were infrastructure-related, though there was also funding for white-collar and artistic work. The program hired librarians, musicians, writers, seamstresses, teachers, researchers, doctors, architects, and more. At its peak, it employed about 3.5 million people, over 6% of the labor force.

Further stimulus came in 1936, with a large early payment of a veterans’ bonus. This program is a particularly good example of a government borrowing in order to make direct cash transfers to households. What the governments literally did was to give the veterans non-marketable bonds, which could be exchanged for an immediate payment or held until maturity, paying an above-market discount rate. Also, veterans who had previously borrowed from the government against their future bonus payment received interest forgiveness. Eighty percent of the bonds were cashed in 1936, and the average recipient received approximately $500, more than the median individual annual income at that time. In total, the program represented a fiscal stimulus equal to approximately 2% of nominal GDP. The bonus recipients appeared to have a high tendency to spend the bonus and often used it to make down payments on purchases with credit, like residential investment and car purchases.

Throughout this period, the US rolled out a number of other programs that used fiscal incentives and macroprudential easings to stimulate credit and spending. These programs both supported existing borrowers and encouraged new lending for residential investment:

- In 1932, Congress created the Federal Home Loan Bank System to act as a quasi-central bank and provide funding for S&L banks, and to set underwriting standards and collateral restrictions.

- In 1933, the Home Owners Loan Act provided a federal guarantee to refinance mortgages on homes costing less than $20,000.

- In 1934, the Federal Reserve was given the ability to set margin requirements (Regulation T) to purchase stocks. It began with “extremely lenient” margin requirements (according to a later Federal Reserve report) of 45%, at about the same level as a rule recently introduced by the New York Stock Exchange.

- In 1934, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to insure home loans, which allowed easier underwriting standards (80% LTV and 20-year maturity) for insurance-eligible loans than what the private market was providing. One FHA program insured 20% of loans for improving residential properties, with up to a 5-year maturity.

- In 1934, Roosevelt set up the Electric Home and Farm Authority to provide cheap loans for home electric appliances (under 10% interest rate, 5% down payment) for up to 36 months.

- In 1935, Congress eased LTV and maturity restrictions for national banks (used to be only up to 5-year loans and 50% LTV, now 10-year and 60% LTV).

- In 1937, the Federal Reserve lowered the equity margin requirement to 40% in response to the downturn (it had been increased in 1936).

Roosevelt’s fiscal spending programs were financed by a combination of spending cuts (Roosevelt cut back on the military early in his presidency) and deficit spending. This deficit spending wasn’t primarily financed by direct QE. The persistent gold inflows that followed the US’s devaluation increased the money supply: the banks, unwilling to increase lending to the private sector, significantly increased holdings of government debt to make a nearly guaranteed spread while funding government spending.

Government Response to 1937–38 Downturn

In 1937, the US entered a significant downturn—stocks declined more than 50%, growth turned negative, and the US slipped back into deflation. We won’t discuss the causes of this downturn, as we’ve described them before, but reductions in the WPA employment program and the fading effects of the veterans’ bonus in 1936 were significant contributors, along with devaluations in France and Italy causing dollar appreciation, sterilization of gold inflows, and increasing bank reserve requirements.

In 1938, the US eased monetary and fiscal policy in response to the downturn. In February of that year, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. ended the gold sterilization program and began desterilizing the accumulated sterilized gold—moves akin to money printing. But policy makers discovered that their actions had very little effect—i.e., they were pushing on a string. From 1938 to 1940, increasing the money supply increased total bank reserves, but the new money was largely held as cash reserves, preventing it from flowing through to the real economy.

The government also passed a $2 billion fiscal stimulus bill, which included a significant increase in the WPA program (it had its biggest year in 1938). While these measures had some effect, the initial improvement in the economy was muted. Industrial production did not recover to peak levels until late 1939, inflation hovered around zero until late 1940, and equities remained approximately 30% below the level of early 1937.

The eventual pickup in economic activity in the US seems largely attributable to World War II. Prior to the US entering the war, production and government spending increased in order to supply the Allies and prepare for potential war. Meanwhile, gold inflows accelerated as investors sought a safe haven from the political situation of Europe and as the Allies began to purchase American supplies (prior to the enactment of Lend-Lease in March 1941).

Eventually, the common cause of World War II united the country and created a political consensus around policies of coordinated and extremely stimulative fiscal and monetary policy. The Federal Reserve summarized its “primary duty” in wartime as “the financing of military requirements and of production for war purposes.” Eccles, who was chair of the Fed through 1948, described his work as “a routine administrative job…The Federal Reserve merely executed Treasury decisions.” During World War II, government spending massively increased, and the money supply more than doubled. The Federal Reserve monetized government spending by maintaining a cap on long-term Treasury bond rates of 2.5% and short-term rates of 0.375%, and by stepping in to buy bonds when rates approached those levels.

Though the world was less globalized in the 1930s than it is now, the debt problems were then (like now) still global and interrelated. We could show you similar developments in a number of countries but, in the interest of brevity, will only touch on what happened in Japan and Germany. Similar things happened in many other countries.

For more historical examples, please visit www.economicprinciples.com

Flavors of Monetary Policy 3

How Directly Do They Receive Stimulus?

Most Direct

Central bank provides printed money to directly to government

QE in which debt is"retired" (government doesn't have to pay back)

Central bank lends to semi-private entities that implement fiscal spending (e.g, development banks)

Big fiscal easing at the same time as big QE

Targeted to Public Sector

Least Direct

Direct Debt Jubilee (big debt write down)

Indirect Debt"Jubilee" (lowering the real cost of debt repayment via devaluing money)

QE that buys real assets (e.g. buying land to build parks)

Both

Central bank provides printed cash directly to households (helicopter money)

Central bank having some control over tax rates, financing tax cuts with printed money

Extremely negative interest rates, passed on to households

Central banks provide very strong economic incentives for banks to end

Targeted to Private Sector

Who is Stimulated to Spend?

金融政策の特徴3

彼らはどの程度直接的に刺激を受けますか? [縦]⬆︎⬇︎

誰が過ごすように刺激されますか?[横]◀︎▶︎

◀︎[公共部門をターゲットにしている]

最も直接的

⬆︎

中央銀行は印刷されたお金を直接政府に提供します

債務が「回収」されたQE[量的緩和](政府は返済する必要はありません)

中央銀行は、財政支出を実施する準民間企業(開発銀行など)に融資します。

大きなQEと同時に大きな財政緩和

⬇︎

最小直接

▶︎[両方]◀︎

⬆︎

直接借入金ジュビリー

間接債務 "Jubilee[特赦]"(金額の切り下げにより債務返済の実質コストを削減)

実物資産を購入するQE(例:公園を建設するための土地の購入)

⬇︎

▶︎[民間セクターをターゲットにしている]

⬆︎

中央銀行は世帯に直接印刷された現金を提供します(ヘリコプターのお金)

中央銀行は税率をある程度管理し、印刷されたお金で減税に資金を供給している

極端にマイナスの金利、世帯に渡される

中央銀行は、銀行が終焉するための非常に強力な経済的インセンティブを提供します。

⬇︎

1 Comments:

799 金持ち名無しさん、貧乏名無しさん[] 2019/08/10(土) 20:21:20.22 ID:6yONOuvf

30分で判る 経済の仕組み Ray Dalio

983,844 回視聴

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NRUiD94aBwI

Principles by Ray Dalio

2014/05/20 に公開

www.EconomicPrinciples.org

コメントを投稿

<< Home