代表的論文Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from US Regions† By Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson (2014)

http://www.columbia.edu/~en2198/papers/fiscal.pdf 40全 最新論文 リンク切れ

ワーキングペーパー

https://www.nber.org/papers/w17391.pdf

付録

https://assets.aeaweb.org/asset-server/articles-attachments/aer/app/10403/20111109_app.pdf

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2020/02/nakamura-emi.html

High Frequency Identication of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect Emi Nakamura and J´on Steinsson∗ Columbia University January 12, 2018

https://eml.berkeley.edu/~enakamura/papers/realrate.pdf 73全

「世界のナカムラ」が切り開く低金利時代の経済学:日経ビジネス電子版

https://business.nikkei.com/atcl/seminar/19/00030/062100027/?n_cid=nbponb_twbnhttp://www.columbia.edu/~en2198/papers/fiscal.pdf 40全 最新論文 リンク切れ

ワーキングペーパー

https://www.nber.org/papers/w17391.pdf

付録

https://assets.aeaweb.org/asset-server/articles-attachments/aer/app/10403/20111109_app.pdf

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2020/02/nakamura-emi.html

High Frequency Identication of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect Emi Nakamura and J´on Steinsson∗ Columbia University January 12, 2018

https://eml.berkeley.edu/~enakamura/papers/realrate.pdf 73全

Does fiscal stimulus work in a monetary union? Evidence from US regions

https://voxeu.org/article/does-fiscal-stimulus-work-monetary-union-evidence-us-regions

財政刺激策は通貨同盟で機能しますか?米国の地域からの証拠

今日の豊かな世界の多くの政府が直面している大きな問題は、政府支出を増やすことによって経済を刺激しようとするべきかどうかです。この質問に関する経済学者の専門的な意見は大きく分かれています。多くのエコノミストは、政府支出の増加が大きな「乗数」効果、すなわち支出の増加以上に生産量を増加させる可能性があると信じていますが、他の多くはこれに懐疑的であり、政府支出の増加が回復を損なうかもしれないとさえ信じています。

この意見の不一致の主な理由は、財政刺激策の効果に関する説得力のある経験的証拠を構築することが難しいことで有名です。経験的な課題はおなじみのものです。相関は因果関係を意味しません。財政刺激策の場合、政府は、財政危機などの理由で生産が低い場合、政府が支出を体系的に増やす傾向があるため、政府支出の多い時期に生産が高いかどうかを確認するという単純なアプローチは機能しません。 。単純な相関関係は、政府

支出と他の要因の影響を「混同」します。必要なのは、ある種の「自然実験」、つまり政府支出の疑似ランダム変動です。

この問題を克服するための1つのアプローチは、20世紀の戦時の軍事支出に対する米国の生産量の反応を研究することです(Ramey and Shapiro 1989、Ramey 2011、Barro and Redlick 2011、Hall 2009)。ここでの考えは、これらの戦争は当時の米国経済の状態とはほとんど関係のない地政学的要因によって引き起こされたということです。ただし、大規模な戦争はほとんどありません。また、戦争はしばしば愛国心の高まりと経済に直接影響を与える可能性のある経済活動の規制を伴います。そして、水をさらに混乱させるために、戦争の資金を調達するために同時に増税される範囲に大きなばらつきがあります。これらの理由から、私たちがこれらの戦争から学ぶことができることはあまりありません。

軍事費の地域差を使用して乗数を特定する

これらの問題は、政府支出の疑似ランダム変動の他のソースの探求を動機付けます。最近の研究では、私たちのアプローチは、米国における軍事支出の地域差を活用することでした(Nakamura and Steinsson 2011)。米国が軍事力増強に着手すると、一部の州では他の州よりも支出が増加する傾向があるという事実を利用しています。たとえば、米国の総軍事支出がGDPの1%増加すると、カリフォルニアの軍事支出は平均でカリフォルニアのGDPの約3%増加しますが、イリノイの軍事支出はイリノイのGDPの約0.5%しか増加しません。カリフォルニアのような州はイリノイのような州に比べてひどく行動しているため、米国はベトナム戦争のような軍事力の蓄積に着手しないという仮定の下で、これらの蓄積に関連する地域の変動を使用して、支出の相対的増加の効果を推定することができます相対出力。私たちの結論は、

州の相対的な支出がGDPの1%増加すると、相対的な州のGDPは1.5%増加するということです。

他の多くの著者が最近、同様の相対的な乗数を推定するために、支出における他の国の変動のソースを悪用しました。たとえば、Shoag(2011)は、州の年金制度への棚ぼた返還に関連する支出の増加を研究しています。 Acconcia et al(2011)は、政治腐敗の証拠によって引き起こされたマフィアに対する法的に強制された取り締まりに関連したイタリアの州レベルの支出の削減を研究しています。 Chodorow-Reich et al(2011)、Clemens and Miran(2011)、Cohen et al(2011)、Fishback and Kachanovskaya(2011)、およびWilson(2011)の研究も参照してください。これらの論文の大部分は、相対的な支出に対する相対的な支出の影響を見積もっており、これは我々が見積もったものと同程度かそれよりも大きかった-1.5から2.5の間の乗数。

1.5の乗数は大きすぎて本当ではありませんか?

一見したところ、これらの乗数は非常に大きく(たとえば、Barro and Redlick 2011およびRamey 2011の推定と比較して)、したがって追加の財政刺激策の支持者にとって好ましいように見えるかもしれません。ただし、これらの実験結果を解釈する際には注意が必要です。

推定値と集計データに基づく古い証拠との違いの1つは、この設定では、支出を得ている地域がそれに対して支払っていないことです。これが、非常に高い乗数推定値を取得している理由でしょうか?新古典主義モデルは実際に反対を提案するでしょう。その理由は、政府の総支出ショックに伴うマイナスの資産ショックが労働供給の増加を引き起こすためです。したがって、このような資産ショックが設定で発生しないという事実は、乗数を上げるのではなく、乗数を下げる必要があります。

もう1つの重要な違いは、イリノイ州に比べてカリフォルニアで支出が増えると、中央政府の政策はこれらの州全体で固定されています。例えば、FRBはイリノイ州に比べてカリフォルニアの金利を引き上げることで対応できず、議会はイリノイ州に比べてカリフォルニアの税率を引き上げることで対応していません。

対照的に、金融および税政策は、政府の総支出ショックに対応して一定ではありません。 「通常の」金融政策-例えば、ポール・ボルカーとアラン・グリーンスパンの指導の下でFRBが実践している政策-は、政府の総計に応じて実質金利を引き上げることにより、またはそれよりも引き下げることにより、かなり積極的に「風に傾く」ことです。 -ショックをかける。政府支出の総体的なショックに対する税政策の対応は、時間の経過とともに変化します。朝鮮戦争中、税金が大量に引き上げられました。これは、最近の軍事力増強には当てはまりません。

地域の消費ショックに対する国家政策の反応と総支出ショックに対するこの違いは、実質的に、政府の支出乗数が比較的緩和的な金融および税政策の反応を条件としていることを意味します。これは、おそらくBarro and Redlick(2011)およびRamey(2011)の乗数推定値よりも乗数推定値が高い理由を説明している可能性があります。

今日、追加の刺激が必要ですか?

それでは、私たちの分析は、今日の追加刺激の影響について何を暗示していますか?分析が示す1つの教訓は、「単一の乗数」はなく、乗数は金融および税政策のスタンスに非常に敏感であることです(この点についてはWoodford 2011も参照)。多くの経済における現在の状況の重要な特別な特徴は、名目金利がゼロの下限に非常に近いことです。この制約は、これらの国の金融当局が望んでいるよりも名目金利が現時点で高い可能性が高いことを意味します。これは、これらの中央銀行が通常のように金利を引き上げることで財政刺激策に対応する可能性が低いことを意味します。言い換えれば、金融政策は、通常の場合よりも今日の財政刺激策に応じて緩和的である可能性が高いということです。

私たちの分析は、この状況に関する推論を導き出すのに特に適していることがわかりました。上記で議論したように、米国は金融と財政の連合であるという事実から、FRBはある地域の金利を別の地域と比べて差別的に引き上げることができず、議会は別の地域に比べてある地域の税率を引き上げないことを知っています。これにより、財政乗数の推定値を解釈する際に重要な「可動部分」が特定されます。

支出の総体的な変動に基づく推定値については、当時の金融および税政策の対応が何であるかがはるかに明確ではないため、これらの推定値を解釈することははるかに難しく、新古典派とニューケインジアンの方法を区別することははるかに困難です政府支出は経済に影響を与えます。

相対的な政策を固定できるという事実により、政府の支出ショックなどの「総需要」ショックが金融政策が十分に緩和的である場合に、アウトプットに大きな影響を与えるニューケインズモデルと推定がはるかに一致していることを示すことができます彼らは、プレーンバニラのネオクラシックモデルです。特に、我々の結果は、経済がゼロ下限にある場合、総計の財政刺激策は大きな生産乗数を持つべきであるという見解を支持しています。

参照資料

Acconcia、A.、G。Corsetti、S。Simonelli(2011)「マフィアと準実験からの財政乗数に関する公的支出の証拠」CEPRディスカッションペーパー8305

バロ、R。J.、およびC. J.レッドリック(2011)「政府の購入と税金からのマクロ経済効果」、Qualityly Journal of Economics、126(1)、51-102。

Chodorow-Reich、G.、L。Feiveson、Z。Liscow、およびW. G. Woolston(2011)「景気後退時の州財政救済は雇用を増加させるか?カリフォルニア大学バークレー校ワーキングペーパー、アメリカの回復と再投資法からの証拠。

Clemens、J.、S。Miran(2011)「雇用と収入に対する州予算削減の影響」、ハーバード大学ワーキングペーパー。

Cohen、L.、J。Coval、C。Mallow(2011)「強力な政治家は企業のダウンサイジングを引き起こしますか?」Journal of Political Economy、近日公開。

フィッシュバック、P。、およびV.カチャノフスカヤ(2010)「ニューディール中の米国における連邦支出の乗数を求めて」、NBERワーキングペーパー第16561号。

ホール、R.E。 (2009)「政府がより多くの生産物を購入した場合、GDPはどの程度上昇しますか」、Brookings Papers on Economic Activity、2009(2)、183-249。

中村E子、J。スタインソン(2011)「米国地域の通貨同盟証拠における財政刺激」、NBERワーキングペーパー17391。

Ramey、V. A.(2011)「政府支出のショックを特定することはすべてタイミングである」、Quarterly Journal of Economics、126(1)、1-50。

ラミー、V。A.、およびM. D.シャピロ(1998)「コストの高い資本の再配分と政府支出の影響」カーネギー・ロチェスター会議シリーズポリシー、48(1)、145-194。

Serrato、J。C. S.、およびP. Wingender(2011)「地方財政の乗数の推定」ワーキングペーパー、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校。

Shoag、D.(2011)「政府支出ショックの影響が州の年金制度の収益からの乗数に及ぼす証拠」ハーバード大学ワーキングペーパー。

Wilson、D. J.(2011)「財政支出の仕事は、2009年のアメリカの回復と再投資法からの証拠を乗じる」、ワーキングペーパー、サンフランシスコ連邦準備銀行。

Woodford、M.(2011)「政府支出乗数の単純な分析」、American Economic Journal Macroeconomics、3(1)、1-35。

A major question facing many governments in the rich world today is whether we should try to stimulate the economy by increasing government spending. The professional opinion of economists regarding this question is sharply divided. While many economists believe that increases in government spending can have large ‘multiplier’ effects – ie increase output by more than the increase in spending – many others are sceptical of this and some even believe that increases in government spending may harm the recovery.

A major reason for this disagreement is that it is notoriously hard to construct convincing empirical evidence on the effects of fiscal stimulus. The empirical challenge is a familiar one; correlation does not imply causation. In the case of fiscal stimulus, the simple-minded approach of seeing whether output is high in periods of high government spending doesn’t work since governments tend to systematically increase spending when output is low for some other reason, eg because of a financial crisis. The simple correlation will then ‘confound’ the effects of government spending with the effects of other factors. What is needed is some sort of ‘natural experiment’, ie pseudo-random variation in government spending.

One approach to overcoming this problem is to study how US output has responded to wartime military spending in the 20th century (Ramey and Shapiro 1989, Ramey 2011, Barro and Redlick 2011, Hall 2009). The idea here is that these wars were caused by geopolitical factors that were largely unrelated to the state of the US economy at the time. However, large wars are few and far between. Also, wars often involve a surge of patriotism and controls on economic activity that can directly impact the economy. And to muddle the water even further, there is a large degree of variation in the extent to which taxes are raised contemporaneously to finance the war. For these reasons there is only so much we can learn from these wars.

Using regional variation in military spending to identify the multiplier

These issues motivate the quest for other sources of pseudo-random variation in government spending. In recent work, our approach has been to exploit regional variation in military spending in the US (Nakamura and Steinsson 2011). We use the fact that when the US embarks upon a military buildup, there is a systematic tendency for spending to increase more in some states than others. For example, when aggregate military spending in the US rises by 1% of GDP, military spending in California on average rises by about 3% of California GDP, while military spending in Illinois rises by only about 0.5% of Illinois GDP. Under the assumption that the US doesn’t embark upon military buildups like the Vietnam War because states like California are doing badly relative to states like Illinois, we can use regional variation associated with these buildups to estimate the effect of a relative increase in spending on relative output. Our conclusion is that when relative spending in a state increases by 1% of GDP, relative state GDP rises by 1.5%.

A number of other authors have recently exploited other sources of sub-national variation in spending to estimate similar relative multipliers. For example, Shoag (2011) studies increases in spending associated with windfall returns to state pension plans; and Acconcia et al (2011) study reductions in provincial-level spending in Italy associated with legally mandated crackdowns on the mafia that were triggered by evidence of political corruption. See also studies by Chodorow-Reich et al (2011), Clemens and Miran (2011), Cohen et al (2011), Fishback and Kachanovskaya (2011), and Wilson (2011). Most of these papers have estimated effects of relative spending on relative output that are of a similar magnitude to those we estimate or somewhat larger – multipliers between 1.5 and 2.5.

Are multipliers of 1.5 too large to be true?

At first glance, these multiplier numbers may seem quite large (eg relative to the estimates of Barro and Redlick 2011 and Ramey 2011) and thus favourable to advocates of additional fiscal stimulus. However, some care is required in interpreting these empirical results.

One difference between our estimates and older evidence based on aggregate data is that in our setting, the region getting the spending is not paying for it. Could this be the reason why we are getting such a high multiplier estimate? Neoclassical models would actually suggest the opposite. The reason is that the negative wealth shock that accompanies an aggregate government spending shock causes an increase in labour supply. The fact that no such wealth shock occurs in our setting should thus lower the multiplier, not raise it.

Another important difference is that when spending increases in California relative to Illinois, national government policy is held fixed across these states. For example, the Fed is not able to respond by raising interest rates in California relative to Illinois, and Congress does not respond by raising tax rates in California relative to Illinois.

In sharp contrast, monetary and tax policy is not constant in response to aggregate government spending shocks. “Normal” monetary policy – eg the policy practiced by the Fed under the leadership of Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan – is to ‘lean against the wind’ quite aggressively by raising real interest rates – or decreasing them by less– in response to aggregate government-spending shocks. The tax policy response to aggregate government-spending shocks varies more over time. During the Korean War, taxes were raised by a large amount. This is less true for more recent military buildups.

This difference between the response of national policy to a regional spending shock and an aggregate spending shock implies that the government spending multiplier we estimate, in effect, is conditioning on a relatively accommodative monetary and tax policy response. This likely explains why our multiplier estimate is higher than those of, eg Barro and Redlick (2011) and Ramey (2011).

Do we need additional stimulus today?

So, what does our analysis imply about the effects of additional stimulus today? One lesson that our analysis illustrates is that there is no ‘single multiplier,’ but rather the multiplier is highly sensitive to the stance of monetary and tax policy (see also Woodford 2011 on this point). An important special feature of the current situation in many economies is that nominal interest rates are very close to their lower bound of zero. This constraint implies that nominal interest rates are likely higher at the moment than the monetary authorities in these countries would like them to be. This means that these central banks are unlikely to respond to fiscal stimulus by raising rates the way they would in normal times. In other words, monetary policy is likely to be more accommodative in response to fiscal stimulus today than in normal times.

It turns out that our analysis is particularly well suited to help us draw inference about this situation. As we discuss above, we know from the fact that the US is a monetary and fiscal union that the Fed can’t differentially increase interest rates in one region versus another and that Congress doesn’t raise tax rates in one region relative to another. This pins down an important ‘moving part’ when it comes to interpreting our estimate of the fiscal multiplier.

For estimates based on aggregate variation in spending, it is much less clear what the monetary and tax policy response was at the time and it is therefore much harder to interpret these estimates and much harder to distinguish between the Neoclassical and the New Keynesian view of how government spending affects the economy.

The fact that we can pin down relative policies allows us to show that our estimates are much more consistent with New Keynesian models in which ‘aggregate demand’ shocks – such as government spending shocks – have large effects on output when monetary policy is sufficiently accommodative than they are with the plain-vanilla Neoclassical model. In particular, our results support the view that aggregate fiscal stimulus should have large output multipliers when the economy is at the zero lower bound.

References

Acconcia, A., G. Corsetti, and S. Simonelli (2011) “Mafia and Public Spending Evidence on the Fiscal Multiplier from a Quasi-Experiment,” CEPR Discussion Paper 8305.

Barro, R. J., and C. J. Redlick (2011) “Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 51-102.

Chodorow-Reich, G., L. Feiveson, Z. Liscow, and W. G. Woolston (2011) “Does State Fiscal Relief During Recessions Increase Employment? Evidence from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” Working Paper, University of California at Berkeley.

Clemens, J., and S. Miran (2011) “The Effects of State Budget Cuts on Employment and Income,” Working Paper, Harvard University.

Cohen, L., J. Coval, and C. Mallow (2011) “Do Powerful Politicians Cause Corporate Downsizing?,” Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Fishback, P., and V. Kachanovskaya (2010) “In Search of the Multiplier for Federal Spending in the States During the New Deal,” NBER Working Paper No. 16561.

Hall, R.E. (2009) “By How Much Does GDP Rise if the Government Buys More Output?,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2009(2), 183-249.

Nakamura, E. and J. Steinsson (2011) “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union Evidence from US Regions,” NBER Working Paper 17391.

Ramey, V. A. (2011) “Identifying Government Spending Shocks It's All in the Timing,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 1-50.

Ramey, V. A., and M. D. Shapiro (1998) “Costly Capital Reallocation and the Effects of Government Spending,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 48(1), 145-194.

Serrato, J. C. S., and P. Wingender (2011) “Estimating Local Fiscal Multipliers,” Working Paper, University of California at Berkeley.

Shoag, D. (2011) “The Impact of Government Spending Shocks Evidence on the Multiplier from State Pension Plan Returns,” Working Paper, Harvard University.

Wilson, D. J. (2011) “Fiscal Spending Jobs Multipliers Evidence from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Woodford, M. (2011) “Simple Analytics of the Government Expenditure Multiplier,” American Economic Journal Macroeconomics, 3(1), 1-35.

「世界のナカムラ」が切り開く低金利時代の経済学:日経ビジネス電子版

「世界のナカムラ」が切り開く低金利時代の経済学

日本にルーツ、気鋭のマクロ経済学者が権威ある賞を受賞

全2547文字

米連邦準備理事会(FRB)が6月19日、米連邦公開市場委員会(FOMC)の会合後に公表した声明文の表現を改めたことから、米国では早期利下げの見方が強まっている。中央銀行が将来の金融政策の方針を前もって表明する「フォワードガイダンス」は日本を含めた中銀が採用している。だが、ある気鋭の経済学者はその効果に懐疑的である。

「フォワードガイダンスは米国や日本で近年、極めて重要な政策になっている。だが低金利の中でさらに利下げを表明したところで、人々の景気の先行き見通しを変えて消費をこれ以上刺激することは難しい。効果は小さなものにとどまるだろう。低金利下では、長期的には政府負債の増大につながるものの、非伝統的な金融政策とともに財政刺激政策を考慮することが重要」――。こう指摘するのは、金融政策や価格の硬直性などを実証研究する米カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の中村恵美(Emi Nakamura)教授である。カナダ国籍と米国籍を持つ日系二世だ。

中村恵美(Emi Nakamura)

米カリフォルニア大学バークレー校教授

1980年10月生まれ。2001年、米プリンストン大学で経済学を学び、最優等で卒業、米ハーバード大学大学院でロバート・バロー教授らに師事、2007年に経済学で博士号取得(Ph.D.)。米コロンビア経営大学院で助教授、准教授、教授を経て2018年から現職。経済学者の夫と子供2人、38歳。

米カリフォルニア大学バークレー校教授

1980年10月生まれ。2001年、米プリンストン大学で経済学を学び、最優等で卒業、米ハーバード大学大学院でロバート・バロー教授らに師事、2007年に経済学で博士号取得(Ph.D.)。米コロンビア経営大学院で助教授、准教授、教授を経て2018年から現職。経済学者の夫と子供2人、38歳。

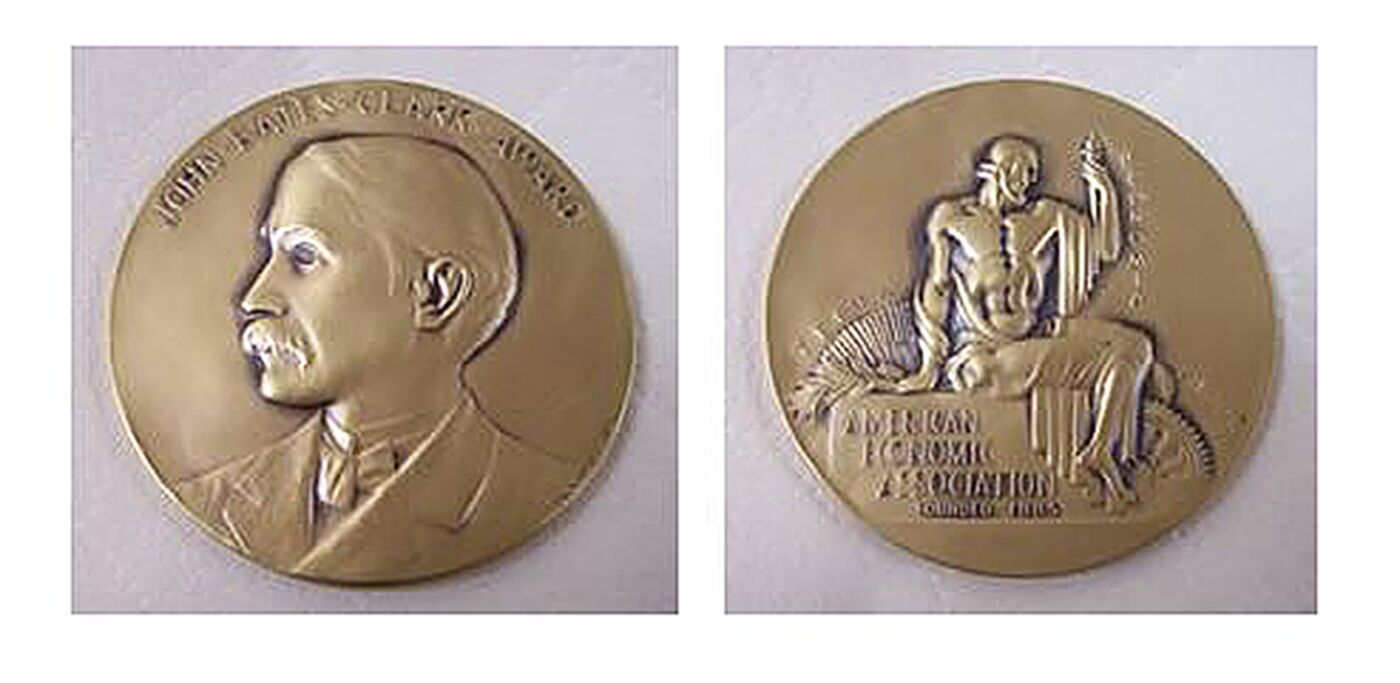

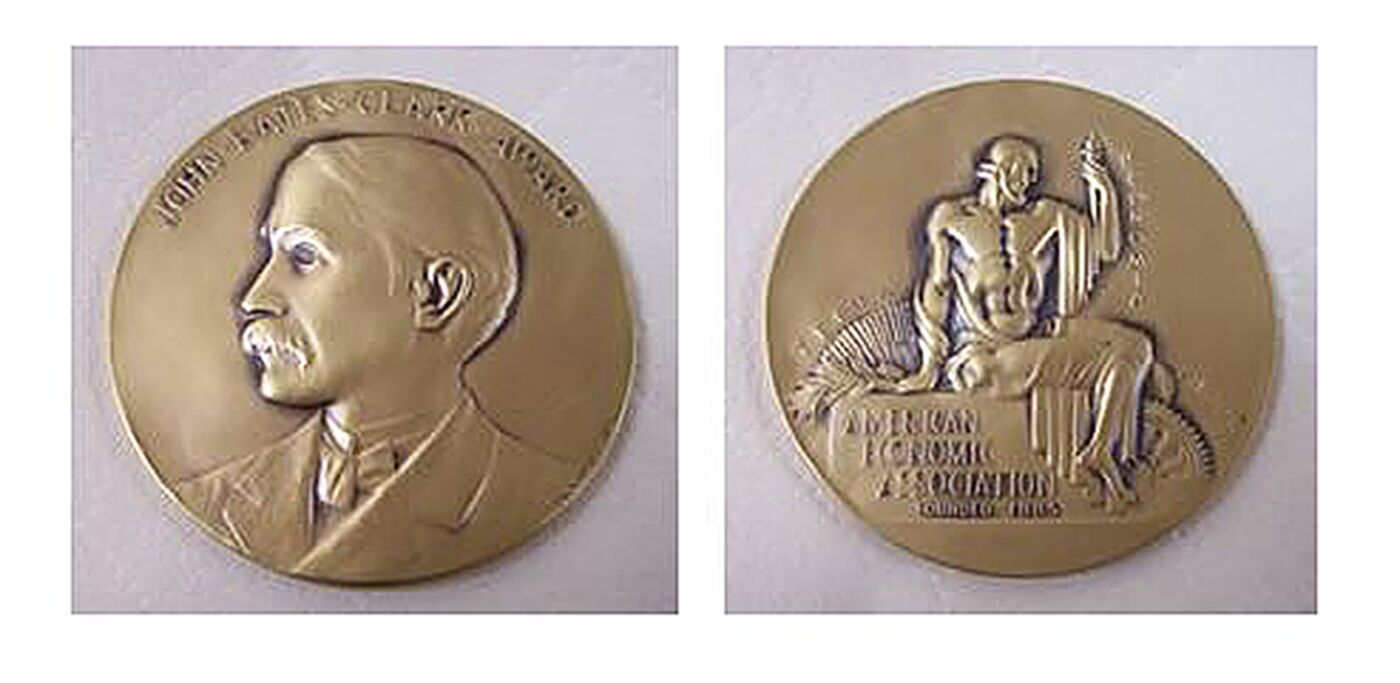

中村教授はこのほど、40歳以下の米国の経済学者に与えられる「ジョン・ベーツ・クラーク賞」を受賞した。同賞は、ノーベル経済学賞の登竜門といわれ、過去には故人のポール・サミュエルソンやミルトン・フリードマンをはじめ、現在も活躍するロバート・ソロー教授やポール・クルーグマン教授、ジョセフ・スティグリッツ教授ら、のちにノーベル経済学賞を受賞した著名な経済学者が受賞者に名を連ねる。

金利がゼロより下がらない状況の中、非伝統的な金融政策が多くの国で採用されてきたが、その正当性は理論モデルで担保されていると考えられてきた。最も典型的なものがフォワードガイダンスだ。「フォワードガイダンスはニューケインジアンと呼ばれる我々世代の研究者が提案したもの」と、東京大学大学院経済学研究科の渡辺努教授はいう。「しかしその理論モデルがよって立つ仮定の吟味が不十分だった。実際、フォワードガイダンスは当初考えられていたほどの効果を発揮しておらず、仮定が正しくなかったことを示している。中村教授らは仮定を丁寧に見直すことで、ゼロ金利下の金融政策の議論に大きな影響を及ぼした」。

またこれまで注目を浴びた研究の一つに、夫であるアイスランド人のジョン・スタインソン米カリフォルニア大学バークレー校教授と発表した論文がある。米国州政府を国とみなし、合衆国を通貨連盟に見立てながら、各州のGDP(域内総生産)と軍事支出の解析を通じて低金利の先進国における財政刺激策の有効性を検証したもので、冒頭のコメントの裏付けの1つともなる知見を提供している。

「世界のナカムラ」が切り開く低金利時代の経済学 (2ページ目):日経ビジネス電子版

https://business.nikkei.com/atcl/seminar/19/00030/062100027/?P=2「世界のナカムラ」が切り開く低金利時代の経済学

日本にルーツ、気鋭のマクロ経済学者が権威ある賞を受賞

全2547文字

「マクロ経済学の仮説を疑え」

中村教授の研究が際立っているのは、個別製品の実際の価格改定の頻度など、これまでマクロ経済の分析では使われることの珍しかった現実の生データを入手し、地道に分析し続けてきた点にある。フォワードガイダンスの検証のみならず、「物価は変わりにくい」「デフレは悪い」といった、過去のマクロ経済学者が当然として受け入れてきた仮定を疑い、実証研究を積み重ねながら挑んできたのだ。

上記2つの疑問に対する現在の中村教授の答えは以下。マクロ的な物価は変動しにくいか? 「科学的根拠から、やはりしにくいことが分かった」。「デフレ」は悪いことか? 「価格が下落している時に名目金利がゼロ近くになっていると、実質金利がかなり高くなってしまう。それが消費者の需要減につながり、景気後退につながり得る」。

「中村教授と(夫である)スタインソン教授による一連の研究は、その後の研究にとって標準、ベンチマークとなっている」と、阿部修人・一橋大学経済研究所教授は評する。東大の渡辺教授は「中村教授らの真骨頂は、マクロ経済学で当たり前とみなされてきた仮定をデータで検証しようとしてきた独自の視点と研究のセンス」という。

「中央銀行の役割は価格を安定させることで、その理屈は理論モデルに基づく。だが理屈がよって立つ仮定が正しいかどうかの確認はできていなかった。また物価安定が損なわれた時、理論モデルが想定するような悪いことが本当に起きるのかどうかもわかっていなかった。基礎的なことが理解できていないので、日本のデフレについて『デフレでもいいじゃないか』と言う人が現れても学者はきちんと反論できない。中村教授らは、これまで確認を怠ってきた重要な事項について、実際のデータを駆使しながら迫り、大きな成果を挙げた」(渡辺教授)。

つまり中村教授らの研究は、2008年のリーマン危機以降すっかり勢いをなくしていたマクロ経済学に、科学的根拠に基づく研究手法を取り入れることによって、新風を吹き込んできたのだ。

父方の祖父は生前、東京・台東区で豆腐店を経営

中村教授は「学者一家」の生まれ。父親は慶應義塾大学卒で元東芝のエンジニアであった経済学者、中村政男カナダ・ブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学名誉教授。母親は米国人経済学者アリス・ナカムラ・カナダ・アルバータ大学教授。兄のケン・ナカムラ氏が米カリフォルニア大学サンフランシスコ校准教授の神経学者だ。

「子供のころ、よく母に経済学会に連れていかれ、いろいろな経済学者と知り合った。家では常にデータで解明することの重要性を両親が議論していたので、かなり影響を受けたと思う」と本人は話す。

日常的に使うのは英語だ。とはいえ父方の祖父は生前、東京・台東区で豆腐店を営み、幼少期の夏を日本で過ごした。幼稚園から小学校まで毎夏来日しては1カ月間、同区の竹町小学校(現・平成小学校)に通い、日本の小学校の掃除当番や給食など、日本ならではのカリキュラムを楽しんだという。

また最近の研究では、米国において、過去には女性の景気回復時における労働市場への参入スピードが男性より速かったのが、近年は女性も男性と同じような動きをすることになったため、雇用回復全体も遅くなったとする研究や、転職頻度が景気とどう関係するかに注目する研究など、労働市場に関する研究にも意欲的に取り組んでいる。

ーーーー

Emi Nakamura(アメリカ国籍) 2019年クラーク賞受賞

Emi Nakamura, Clark Medalist 2019

Emi Nakamura(米国籍)の論考はマンキューマクロ入門篇でも言及されている。邦訳第4版。

新第9章のケース・スタデイ「乗数の推定における地域デー夕の利用」(348頁)で新たに参照(349頁)されたのは

以下の論文。

エミ・ナカムラとジョン・スタインソン

Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from US Regions

By Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson*

軍事予算の乗数効果を扱った異色の論考。

メニューコストなど価格理論が有名。

2015年インタビュー

母親(もまた高名な経済学者)のインタビュー

Nobel Symposium Emi Nakamura Monetary policy: Conventional and unconvent...

2018年 33:21

インフレターゲットについて

Second ECB Annual Research Conference - Paper 8: The elusive costs of i...

2017年 55:32

Fiscal policy

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2014). "Fiscal stimulus in a monetary union: Evidence from US regions". The American Economic Review. 104 (3): 753–792. JSTOR 42920719. uses regional variation in US military spending to estimate an "open economy multiplier" of 1.5. This empirical evidence "indicates that demand shocks can have large effects on output", particularly at the zero lower bound.[12]

Another area in which Emi Nakamura has had a significant impact is in the study of the effects of government spending shocks, a classic issue in macroeconomics that has been of renewed interest following the widespread use of fiscal stimulus measures by governments in response to the global financial crisis. Estimates of the size of the government spending multiplier have been quite dispersed and remain highly controversial. Nakamura’s work with Jón Steinsson in “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from U.S. Regions” (AER 2014) brought new data and a fresh identification approach to an important debate.

中村恵美が大きな影響を及ぼしたもう1つの分野は、政府の支出ショックの影響の研究であり、これは世界的な金融危機に対応して政府による財政刺激策の広範な使用の後に新たな関心が寄せられている。危機。 政府支出の乗数の大きさの見積もりはかなり分散しており、非常に物議を醸すままである。 「通貨同盟における財政刺激:米国地域からの証拠」( AER 2014)における中村のジョン・スタインソンとの共同研究は、新しいデータと新たな識別アプローチを重要な議論にもたらしました。

ーーーーー

彼らの最も引用されている論文「価格に関する5つの事実:メニューコストモデルの再評価」( QJE 2008)では、中村とSteinssonは、米国の公表消費者物価指数と生産者物価指数の構築に使用される個々の価格に関するBLSデータを研究します。これは、一般的な価格調整の理論モデルである「メニューコスト」モデルの意味と比較することができます。 彼らは、物価変動の平均頻度、すなわち金融政策の効果の定量的モデルの数値校正における重要な問題に特に注意を向けています。 他の情報源を使った過去の研究では、米国経済の価格変動間の時間の中央値はほぼ1年であると結論づけられていましたが、BLSマイクロデータ(Mark BilsとPete Klenowによる)を使った最初の研究は、実際には、価格はずっと頻繁に変化しました(期間の中央値は4ヶ月強に過ぎません)。 BilsとKlenowは、実際にはBLSマイクロデータセットを使用していませんでしたが、1995年から1997年までの期間の値からの抜粋で、非常に細分化されたレベルでの価格変動の平均頻度を報告しました。 中村とSteinssonは代わりにBLSによって使われた実際のミクロデータへのアクセスを得ました、そしてそれはBLSによってそして1988年から2005年までの期間の間に集められたすべての価格観察を持っています。

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2008). "Five facts about prices: A reevaluation of menu cost models". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 123 (4): 1415–1464. JSTOR 40506213. This paper analyzes detailed microeconomic price data and describes firms' price-setting behavior to test the menu cost model of price stickiness. They find mixed evidence: some facts in the data are consistent with the menu cost model, but others are not.

インフレと価格の変動

中村はまた、金融政策の効果の実証分析にも重要な貢献をしてきました。 「貨幣的な非中立性の高頻度な識別:情報効果」(QJE、2018年、Steinssonとの共著)は、2000年1月から2014年3月までの間に予定されている106の連邦準備制度の発表を中心に30分の時間枠で金利の変化を研究している。関連文献の標準では、この30分の間に見られた金融市場の変化は、連邦準備制度理事会の発表で発表された情報に起因しています。 しかし、そのような金融政策への衝撃の「高頻度の識別」の初期の支持者とは異なり、NakamuraとSteinssonは明らかにされたニュースは与えられた経済的ファンダメンタルズに対する期待される金融政策の変化を表すだけではないと認識する。 それはまたFRBが認識しているが市場はまだ認識していなかったかもしれない経済の状態についてのニュース、またはFRBが発表の前に市場が信じていたものとは異なる経済の現状をどう解釈するかについてのニュースを含むことができます。 本稿の貢献は、そのような情報効果の存在の可能性を考慮しながら、金銭的な非中立性についての推論を引き出すことと、FRB発表の観測された効果を説明できる理論モデルを構築し推定することです。

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon; Sun, Patrick; Villar, Daniel (2018). "The Elusive Costs of Inflation: Price Dispersion during the U.S. Great Inflation" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 133(4): 1933–1908. attempts to measure the costs of inflation. In the commonly used New Keynesian macroeconomic models, the social costs of inflation arise from inefficient price dispersion: higher inflation implies higher price dispersion. Nakamura et al. digitize price data from the era of high inflation in the US in the 1970s and 1980s to test this hypothesis. They find "no evidence that the absolute size of price changes rose during the Great Inflation", and conclude that "This suggests that the standard New Keynesian analysis of the welfare costs of inflation is wrong and its implications for the optimal inflation rate need to be reassessed".

中村恵美(2018)。 「貨幣の非中立性の高周波識別:情報効果」 (PDF) 季刊経済ジャーナル 。 133(3):1283-1330。 連邦準備制度の金利発表後30分のウィンドウで、実質変数(実質金利、経済成長率)に対する金融市場の期待の変化を示しています。

☆

Emi Nakamura, Clark Medalist 2019

American Economic Association Honors and Awards Committee

April 2019

April 2019

Emi Nakamura is an empirical macroeconomist who has greatly increased our understanding of price-setting by firms and the effects of monetary and fiscal policies. Nakamura’s distinctive approach is notable for its creativity in suggesting new sources of data to address long-standing questions in macroeconomics. The datasets she uses are more disaggregated, or higher-frequency, or extending over a longer historical period, than the postwar, quarterly, aggregate time series that have been the basis for most prior work on these topics in empirical macroeconomics. Her work has required painstaking analysis of data sources not previously exploited, and at the same time displays a sophisticated understanding of the alternative theoretical models that the data can be used to distinguish.

Nakamura is best known for her use of microeconomic data on individual product prices to draw conclusions about the empirical validity of models of price-setting used in the macroeconomic literature; this has been a critical issue for analysis of the short-run effects of monetary policy. Studies of the adjustment of individual prices—in particular, measures of the average time that prices are observed to remain unchanged—have long been a key source of evidence regarding the importance of price rigidity. However, until very recently most evidence of this kind came from studies of a very small number of markets, so that the question of how typical these specific prices were remained an important limitation. The availability of new data sets that allow changes in the prices of a very large number of goods to be tracked simultaneously has radically transformed this literature over the past fifteen years, and Nakamura, together with her frequent co-author Jón Steinsson, has played a leading role in this development.

In their most-cited paper, “Five Facts About Prices: A Re-Evaluation of Menu Cost Models” (QJE 2008), Nakamura and Steinsson study the BLS data on individual prices used to construct the published consumer and producer price indices for the U.S. economy, documenting a variety of facts about changes in individual prices that can then be compared to the implications of a popular theoretical model of price adjustment, the “menu cost” model. They give particular attention to the average frequency of price changes, an important issue in the numerical calibration of quantitative models of the effects of monetary policy. While past studies using other sources had concluded that the median time between price changes in the U.S. economy was nearly a year, the first work using the BLS microdata (by Mark Bils and Pete Klenow) had argued that the BLS data underlying the CPI showed that prices actually changed much more frequently (a median duration of prices only a little over 4 months). Bils and Klenow actually did not use the BLS micro dataset, but rather an extract from it for the period between 1995 and 1997 that reported average frequencies of price changes at a very disaggregated level. Nakamura and Steinsson instead obtained access to the actual micro data used by the BLS, which has all the price observations collected by the BLS and for the period from 1988 to 2005.

Revisiting Bils and Klenow’s conclusion using their superior dataset, Nakamura and Steinsson show that one’s conclusions about the frequency of price changes in the CPI data depend on the method used to distinguish sales from changes in “regular prices.” They also study the changes in individual wholesale prices and consumer prices. They find both that changes in regular prices occur much less often than price changes that include sales (they find a median duration of 8-11 months for regular prices, depending on the precise method used to classify price changes), and that producer prices (for which there is less of a need to filter out “sales”) also change quite infrequently. A first reason why this paper is so influential is that it gives very convincing microeconomic evidence for much more substantial “stickiness” of individual prices than the surprising results of Bils and Klenow had implied. The paper is also valuable for documenting features of the data on individual price changes that can be used to test the realism of specific models of price adjustment. Nakamura and Steinsson stress two features of the data that are contrary to the predictions of a popular class of models of price adjustment (“menu-cost” or “S-s” models): clear seasonality in the frequency of price adjustments, and the failure of the hazard function for price changes to increase in the time since the last change in price.

The ability of a “menu-cost” model to account for the quantitative characteristics of the micro data on price changes is considered further in “Monetary Non-Neutrality in a Multi-Sector Menu Cost Model” (QJE 2010, also with Steinsson). Prior numerical analyses of the implications of menu-cost models (such as the influential paper by Golosov and Lucas) had assumed that all goods in the economy were subject to menu costs of the same size (in addition to being produced with the same technology), with the parameters common to all goods being assigned numerical values to match statistics for the set of all price changes (such as the overall frequency of change in prices and the average absolute size of price changes). But one of the facts documented by Nakamura and Steinsson in “Five Facts” is that there is tremendous heterogeneity across sectors of the U.S. economy in the frequency of non-sale price changes.

In the “Monetary Non-Neutrality” paper, they calibrate a multi-sector menu-cost model to also match the distribution across sectors of both the frequency of price changes and the average size of price changes. They find that the real effects of a monetary disturbance are three times as large in their multi-sector model as in a one-sector model (like that of Golosov and Lucas) calibrated to the mean frequency of price change of all firms. Indeed, whereas Golosov and Lucas argue that price rigidity is not an empirically plausible explanation for the observed effects of monetary disturbances, if one takes account of the micro evidence on the frequency of price adjustments, Nakamura and Steinsson show that their calibrated multi-sector model (with nominal shocks of the magnitude observed for the U.S. economy) predicts output fluctuations that would account for nearly a quarter of the U.S. business cycle. This would be roughly in line with the fraction of GDP variability that is attributed to monetary disturbances in atheoretical vector-autoregression studies. The paper’s emphasis on the importance of taking account of sectoral heterogeneity when parameterizing the degree of price stickiness has been highly influential.

More recently, Nakamura and Steinsson have devoted considerable effort to extending the BLS micro-level data set on consumer prices back to 1977. This labor-intensive, multiyear data-construction project is of interest because the extended database now includes the period in the late 1970s and early 1980s when inflation was much higher and more volatile than it has been since 1988. The first paper making use of the extended data set is with Patrick Sun and Daniel Villar, “The Elusive Costs of Inflation: Price Dispersion During the U.S. Great Inflation” (QJE, forthcoming). The paper considers how the firms’ adjustment of their prices to changing market conditions differs in a higher-inflation environment. The authors find that “regular” (i.e., non-sale) prices were adjusted more frequently in the earlier (higher-inflation) part of their data set, and by about the amount that would be predicted by a model of optimal price adjustment considering a fixed cost (a “menu cost”) of adjusting the firm’s price. They conclude from this that it is important, when assessing the welfare costs expected to follow from choosing a permanently higher rate of inflation, to take account of the increased frequency of price adjustments that should be expected to occur, keeping prices from being as far out of line with current conditions as would otherwise be expected in a more inflationary environment.

The paper also seeks to measure the degree to which there is greater dispersion in the prices of similar products in a higher-inflation environment. Some common models of price adjustment imply that there should be: given staggering of the times at which different firms’ prices happen to be reconsidered, the price that is optimally chosen would vary depending on the rate at which prices in general increase from week to week. If so, this should be an important source of increased distortion of the allocation of resources in a higher-inflation environment. Measurement of the degree of dispersion in the prices of genuinely identical goods is difficult, since different prices for different firms’ goods might reflect heterogeneity of the goods, so that they would have different prices even with fully flexible prices.

For this reason, the authors propose instead to look at the how the average size of price changes (when prices are adjusted) differs between high- and low-inflation periods; the idea is that if prices are adjusted to their currently optimal level whenever they are changed, the size of the price changes that are observed indicates how far prices have drifted from their optimal level just before they are adjusted. They find that the average size of price increases, when they occur, is about the same (a 7 percent increase on average) in their pre-1988 sample as in their post- 1988 sample. Again, they interpret this as evidence that the timing of price changes adjusts endogenously when the rate of inflation increases, in such a way as to reduce the distortions created by inflation relative to what one would expect if the timing of price adjustments were independent of the degree to which a given firm’s prices have gotten out of line with current market conditions. The authors conclude that the welfare costs of chronically higher inflation may not be as large as welfare calculations based on sticky-price models with an exogenous frequency of price adjustment would suggest. The paper is simultaneously an important contribution to policy debates about the costs of inflation; to our understanding of historical facts about price adjustment in the US; and to the empirical basis for assessing the realism of alternative theoretical models of price-setting.

Another area in which Emi Nakamura has had a significant impact is in the study of the effects of government spending shocks, a classic issue in macroeconomics that has been of renewed interest following the widespread use of fiscal stimulus measures by governments in response to the global financial crisis. Estimates of the size of the government spending multiplier have been quite dispersed and remain highly controversial. Nakamura’s work with Jón Steinsson in “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from U.S. Regions” (AER 2014) brought new data and a fresh identification approach to an important debate.

An important problem in estimating the fiscal multiplier is the difficulty of finding truly exogenous changes in government spending. Researchers have for a long time argued that changes in military purchases are a plausible candidate for exogenous variations in government spending. However, there have not been large variations in aggregate military spending since the Korean War, so that aggregate military spending is of limited use for identifying the government spending multiplier for the U.S. economy of the past 50 years. An important insight of Nakamura and Steinsson’s paper is that while in the aggregate there may not have been large variation in U.S. military spending, there has been sizeable variation in regional military spending, and those regional variations can thus be used to estimate a government spending multiplier. Another important problem with previous studies is that the output effects of government spending should very likely (according to standard theory) depend on the nature of the monetary policy reaction. Some have argued that typical studies under-estimate the multiplier by failing to take account of the extent to which output effects are reduced by the typical monetary response to output booms resulting from government purchases outside of deep recessions, even though the likely response during a deep recession would (arguably) be quite different. Nakamura and Steinsson’s strategy sidesteps this problem, since the monetary policy reaction is common to all states, and so should not be a factor in explaining the differential effects on output across states.

A further complication in estimating government spending multipliers is that their size depends on how changes in government spending are financed. Previous studies have struggled with how to take into account financing considerations. An advantage of Nakamura and Steinsson’s empirical strategy is that regional military spending is financed by federal taxation and thus regions that receive a large chunk of military spending will not have tax structures that are different from regions that do not receive military spending. Thus, considering variations in regional military spending and relating it to regional output variations should provide a much more reliable estimate of the government spending multiplier than previous studies.

The paper offers much more than a clever instrument for measuring the multiplier effect of government purchases. The authors point out that the multiplier estimated for the effect of relatively higher purchases in one state on relative economic activity in that state need not be the same as the multiplier for the effect on national GDP of a nation-wide increase in government purchases (the central issue for debates about the effectiveness of “fiscal stimulus” as a response to recession), because of spillovers between states of the effects of increased purchases in any given state. These spillovers occur not only because increased income in one state leads to increased purchases from out-of-state suppliers, while the national economy is less open, but also because increased relative government spending in one state is not financed by increased relative taxation of that state’s residents, while increased national spending will require increased revenue to be raised from US taxpayers in aggregate. Steinsson and Nakamura address the likely magnitude of the difference between the two multipliers by developing and analyzing a quantitative multi-region New Keynesian general-equilibrium model and asking what the national multiplier would be in the case of a model parameterization that can account for their estimated relative state-level effects. The paper provides an excellent example of work that combines non-structural empirical work with careful model-based analysis of what can be learned from the estimates and makes a substantial contribution to an applied literature of considerable importance for macroeconomic policy.

Nakamura has also made important contributions to empirical analysis of the effects of monetary policy. “High Frequency Identification of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect’’ (QJE, 2018, also with Steinsson) studies interest-rate changes in a thirty-minute window around 106 scheduled Federal Reserve announcements between January 2000 and March 2014. As is standard in related literature, financial-market changes observed during this thirty-minute window are attributed to information released in the Federal Reserve announcement. However, unlike some earlier proponents of such “high-frequency identification” of shocks to monetary policy, Nakamura and Steinsson recognize that the news revealed need not only represent a change in expected monetary policy for given economic fundamentals; it could also contain news about the state of the economy that the Fed is aware of but the markets might not have been aware of yet, or news about how the Fed interprets the current state of the economy differently than markets had believed prior to the announcement. The paper's contribution is to draw inferences about monetary non-neutrality while allowing for the possible presence of such information effects, and to build and estimate a theoretical model that can explain the observed effects of Fed announcements.

This problem motivates the development of a model in which Fed announcements can have both an information effect and a pure monetary policy shock, allowing estimation of how big each component in the observed Fed announcements is. The results of this estimation suggest that the proposed model can explain well the observed effects of Fed announcement shocks; that about two-thirds of the announcement shock represents news about future economic fundamentals, and hence that only one-third represents a pure monetary policy shock; and that, despite the great importance of the information effect, the observed responses to Fed announcements are consistent with a high degree of monetary non-neutrality in the U.S. economy. These are important results about fundamental questions in monetary economics, and the paper represents a significant improvement upon prior methodology.

While Nakamura’s most characteristic contributions have been to empirical research, her work is always guided by a sophisticated understanding of the structure of theoretical models, and some of her contributions are primarily theoretical. An important example is her paper “The Power of Forward Guidance Revisited” (AER 2016, with Steinsson and Alisdair McKay). This paper addresses a question about monetary policy that has been a focus of considerable interest in light of central-bank responses to the recent financial crisis both in the US and elsewhere, namely, the extent to which central-bank commitments about future policy (possibly indicating that interest rates should remain at their current level for years into the future) can be an effective way of influencing financial conditions and stimulating aggregate demand, even in the absence of any change in the current level of short-term interest rates.

Simple New Keynesian DSGE models imply that advance commitments to maintain a highly accommodative policy in the future should have a substantial stimulative effect; in fact, in the case of a commitment to low interest rates extending several years into the future, the models predict an immediate effect on both economic activity and inflation that is so strong as to make it difficult to regard this as a realistic prediction—and one that is certainly not consistent with the more modest effects of actual experiments with forward guidance. This has been called “the forward guidance puzzle.” Nakamura and her co-authors argue that the unrealistic implication of the simple New Keynesian models results from the feature that each agent has a single intertemporal budget constraint, as a result of assuming complete financial markets and no borrowing constraints. They analyze the effects of a long-horizon commitment to a fixed nominal interest rate in a model that instead allows for the existence of uninsurable income risk and borrowing constraints and find that while the effects of expectations about monetary policy at shorter horizons are similar to those predicted by the simpler model, the predicted effects of a long-lasting commitment to a fixed nominal interest rate are much weaker. Essentially, they find that in the case of a household with a significant probability of having a point in time over the next several quarters at which its borrowing constraint binds, expectations about monetary policy farther in the future than the time at which the constraint binds do not affect its current ability to spend, and this substantially reduces the predicted effects on current aggregate demand of commitments about policy years in the future.

Their alternative model thus implies that forward guidance is a less powerful tool for getting out of a sharp contraction than simpler models would imply, though it hardly implies that it is irrelevant. The paper is both a contribution to an important policy debate and a useful methodological contribution to the literature on the application of New Keynesian models to assess alternative monetary policies. It has stimulated an active recent literature on “heterogeneous-agent New Keynesian models,” which explores the implications for other aspects of macroeconomic dynamics of introducing income heterogeneity and borrowing constraints.

Nakamura has recently published a JEP article on “Identification in Macroeconomics,” with Steinsson and a new working paper on the role of women’s labor force participation in the slow recovery from recessions observed over the last few decades. The former is an interesting generalization of the approach discussed above in her fiscal policy paper and also in the price-setting papers: using cross-section variation to identify macroeconomic phenomena and disciplining the aggregate implications with careful structural modeling. This approach is common to several of Nakamura’s most influential papers and is methodologically eclectic. It takes advantage of advances in the availability of new and larger data sets to explore cross-section variation, while also recognizing that this alone does not deliver the macroeconomic implications that are of interest to her. The macro implications require modeling of aggregation that takes into account the heterogeneity in the micro data, and equilibrium considerations. Moreover, the macro models have implications for the cross section that are testable and provide additional discipline and ability to distinguish competing macro hypotheses. This approach has also been applied in several of her recent papers on the wealth effect from housing, delivering significantly different implications from work focusing only on the micro data.

The working paper “Women, Wealth Effects, and Slow Recoveries” (with Fukui and Steinsson) on slow recoveries from business cycle downturns documents that the slow recovery phenomenon coincides with the convergence of female’s labor force participation to that of males. That is, as female labor force participation rose during the mid and late-20th century, employment recovered quickly from downturns as women entered the labor force in higher numbers during recoveries. However, as female labor force participation has risen and converged towards men’s, that dynamic has faded. The paper argues that this effect alone accounts for 70 percent of the slowing of economic recoveries. This is an interesting “opposite number” of another labor market finding: that firms adjust faster during downturns, as they adjust to long-run trends more when they are firing. This result suggests a similar finding during upturns, when there is capacity to draw new workers into the labor market.

Prior recognition for Nakamura’s accomplishments includes a CAREER Award from the NSF (2011), a Sloan Research Fellowship (2014), the Elaine Bennett Research Prize from the AEA (2014), being named a member of “Generation Next: Top 25 Economists Under 45” by the IMF (2014), and being named one of the decade’s top eight young economists by the Economist (2018). She serves as a Co-editor of the AER, on the CBO’s Panel of Economic Advisers, the AEA Committee on National Statistics, and the BLS Technical Advisory Committee; these appointments testify to the role she has quickly gained in the profession as an expert on issues relating to data construction. Her contributions to the general methodology of empirical macroeconomics, and to the empirical basis for analyses of the effects of monetary and fiscal policies, make Emi Nakamura an outstanding candidate for this year’s John Bates Clark Medal.

NAMS出版プロジェクト

HTTP://WWW.FREEASSOCIATIONS.ORG/

水曜日、2019年5月1日

優等賞/ベイツクラーク/エミ・ナカムラ

https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea/honors-awards/bates-clark/emi-nakamura

中村恵美、クラークメダリスト2019

アメリカ経済協会名誉賞委員会

2019年4月

中村恵美は経験的なマクロ経済学者で、企業による価格設定と金融政策や財政政策の影響についての理解を大いに高めました。 中村の独特のアプローチは、マクロ経済学における長年の疑問に取り組むための新しいデータ源を提案するというその創造性のために注目に値する。 彼女が使用しているデータセットは、経験的マクロ経済学におけるこれらのトピックに関するこれまでのほとんどの研究の基礎となっていた戦後の四半期ごとの時系列よりも、より分離されていない、より高い頻度で、あるいはより長い歴史的期間にわたって伸びています。 彼女の研究は、以前には利用されていなかったデータソースの骨の折れる分析を必要とし、同時にデータを区別するために使用することができる代替の理論モデルの高度な理解を示しています。

中村は、個々の製品の価格に関するミクロ経済データを使って、マクロ経済文献で使われている価格設定モデルの経験的妥当性について結論を出すことで最もよく知られています。 これは、金融政策の短期的影響を分析する上で重要な問題となっています。 個々の物価の調整、特に物価が変化しないことが観察される平均時間の尺度に関する研究は、物価の硬直性の重要性に関する長い証拠となりました。 しかし、ごく最近まで、この種のほとんどの証拠は非常に少数の市場の研究から来ていたので、これらの特定の価格がどれほど典型的であるかという問題は依然として重要な制限であった。 非常に多数の商品の価格の変化を同時に追跡することを可能にする新しいデータセットの利用可能性は、過去15年間にわたってこの文献を根本的に変革しました、そして中村は彼女の頻繁な共著者JónSteinssonと共にプレーしましたこの開発における主導的役割。

彼らの最も引用されている論文「価格に関する5つの事実:メニューコストモデルの再評価」( QJE 2008)では、中村とSteinssonは、米国の公表消費者物価指数と生産者物価指数の構築に使用される個々の価格に関するBLSデータを研究します。これは、一般的な価格調整の理論モデルである「メニューコスト」モデルの意味と比較することができます。 彼らは、物価変動の平均頻度、すなわち金融政策の効果の定量的モデルの数値校正における重要な問題に特に注意を向けています。 他の情報源を使った過去の研究では、米国経済の価格変動間の時間の中央値はほぼ1年であると結論づけられていましたが、BLSマイクロデータ(Mark BilsとPete Klenowによる)を使った最初の研究は、実際には、価格はずっと頻繁に変化しました(期間の中央値は4ヶ月強に過ぎません)。 BilsとKlenowは、実際にはBLSマイクロデータセットを使用していませんでしたが、1995年から1997年までの期間の値からの抜粋で、非常に細分化されたレベルでの価格変動の平均頻度を報告しました。 中村とSteinssonは代わりにBLSによって使われた実際のミクロデータへのアクセスを得ました、そしてそれはBLSによってそして1988年から2005年までの期間の間に集められたすべての価格観察を持っています。

NakamuraとSteinssonは、優れたデータセットを使用してBilsとKlenowの結論を再考すると、CPIデータの価格変動の頻度に関する結論は、売上を「通常価格」の変動と区別するための方法によって異なることを示しています。卸売価格と消費者価格 彼らは、通常の価格の変更が売上を含む価格の変更よりもはるかに少ない頻度で発生することを発見します(彼らは価格変更を分類するために使用される正確な方法に応じて、通常の価格の中央値8-11ヶ月を見つけます)。 「売上」を除外する必要がほとんどない場合も、ほとんど変わりません。 この論文がそれほど影響力を持っている最初の理由は、BilsとKlenowの驚くべき結果が暗示していたよりもはるかに実質的な個々の価格の「粘着性」について非常に説得力のあるミクロ経済的証拠を与えることです。 このペーパーは、特定のモデルの価格調整モデルの現実性をテストするために使用できる個々の価格変更に関するデータの機能を文書化するのにも役立ちます。 NakamuraとSteinssonは、価格調整モデルの一般的なクラス(「メニューコスト」または「Ss」モデル)の予測に反するデータの2つの特徴を強調しています。価格のハザード関数は、最後の価格変更以降の時間で増加します。

価格変動に関するミクロデータの量的特性を説明するための「メニューコスト」モデルの能力については、「マルチセクターメニューコストモデルにおける貨幣の非中立性」( QJE 2010、Steinssonも同様)でさらに検討されている。 メニューコストモデル(GolosovとLucasによる影響力のある論文のような)の意味の以前の数値分析は、経済のすべての商品が同じサイズのメニューコストの影響を受けると仮定していた(同じ技術で生産されることに加えて)すべての商品に共通のパラメータには、すべての価格変動のセットの統計と一致するように数値が割り当てられています(価格変動の全体的な頻度および価格変動の平均絶対サイズなど)。 しかし、「5つの事実」でNakamuraとSteinssonによって文書化された事実の1つは、非販売価格の変化の頻度において米国経済の部門間で途方もない異質性があるということです。

“ Monetary Non-Neutrality”の論文では、価格変動の頻度と価格変動の平均サイズの両方の部門間の分布にも一致するように、複数部門のメニューコストモデルを調整しています。 彼らは、金銭的混乱の実際の影響は、(GolosovやLucasのような)1セクターモデルの場合と比べて、すべての企業の平均価格変動頻度に合わせて調整した場合の3倍になっていることを見出しました。 確かに、GolosovとLucasは物価の硬直性が金銭的混乱の観察された影響についての経験的にもっともらしい説明ではないと主張する一方、中村とSteinssonは彼らの較正されたマルチセクターモデルを示す(米国経済に見られる規模の名目上のショックで)は、米国の景気循環のほぼ4分の1を占めるであろう生産高の変動を予測する。 これは、理論的ベクトル自己回帰研究における金銭的攪乱に起因するGDPの変動性の割合とおおまかに一致します。 価格の粘着性の程度をパラメータ化する際に部門別の異質性を考慮に入れることの重要性に対するこの論文の強調は、非常に影響力があります。

最近では、NakamuraとSteinssonは消費者物価に関するBLSミクロレベルデータセットを1977年まで拡張することにかなりの努力を注いできました。 1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて、1988年以来、インフレ率がはるかに高く、変動しやすくなりました。拡張データセットを利用した最初の論文は、Patrick SunとDaniel Villarによるものです。インフレ」( QJE、近日発表予定)。 本稿は、変化する市況に対する自社の価格の調整が、インフレ率の高い環境でどのように異なるかを考察しています。 著者らは、「通常の」(すなわち、非販売)価格は、彼らのデータセットの初期(インフレ率が高い)部分でより頻繁に調整され、最適価格調整のモデルによって予測される金額で会社の価格を調整するための固定費(「メニュー費用」)。 彼らは、このことから、恒久的に高いインフレ率を選択することから生じると予想される厚生費用を評価する際には、価格の変動を回避しつつ、発生すると予想される価格調整の頻度の増加を考慮することが重要であると結論する。そうでなければ、よりインフレの高い環境で予想されるように、現在の状況と一致

本稿はまた、インフレ率が高い環境において、類似製品の価格にどの程度のばらつきがあるかを測定しようとしている。 価格調整の一般的なモデルには、次のようなものがあります。さまざまな企業の価格が再考される時期がずれると、最適な価格は週ごとの価格の上昇率によって異なります。 。 もしそうであれば、これはインフレ率の高い環境における資源配分の歪みの増大の重要な原因となるはずである。 真に同一の商品の価格のばらつきの程度を測定することは困難です。なぜなら、異なる企業の商品の異なる価格は商品の不均一性を反映し、完全に柔軟な価格であっても異なる価格を持つからです。

このため、著者らは代わりに、物価変動の平均規模(物価調整時)が高インフレ期間と低インフレ期間の間でどのように異なるかを調べることを提案している。 アイデアは、価格が変更されるたびに現在の最適レベルに調整される場合、観測される価格変更のサイズは、価格が調整前の最適レベルからどれだけ離れているかを示します。 彼らは、発生した場合の平均価格上昇幅は、1988年以前のサンプルでも1988年後のサンプルとほぼ同じである(平均で7%の増加)ことを発見しました。 繰り返しになりますが、彼らはこれを物価変動のタイミングが独立している場合に予想されるものと比較してインフレによって生じる歪みを減らすように、物価変動のタイミングが内在的に調整する証拠として解釈します特定の会社の価格が現在の市況と一致しなくなった程度。 著者らは、慢性的に高いインフレの厚生費用は、外因的な価格調整の頻度を伴うスティッキープライスモデルに基づく厚生計算ほど大きくはないかもしれないと結論付けている。 紙は同時にインフレのコストについての政策論争への重要な貢献である。 米国における価格調整に関する歴史的事実の理解 そして価格設定の代替理論モデルの現実性を評価するための経験的根拠に。

中村恵美が大きな影響を及ぼしたもう1つの分野は、政府の支出ショックの影響の研究であり、これは世界的な金融危機に対応して政府による財政刺激策の広範な使用の後に新たな関心が寄せられている。危機。 政府支出の乗数の大きさの見積もりはかなり分散しており、非常に物議を醸すままである。 「通貨同盟における財政刺激:米国地域からの証拠」( AER 2014)における中村のジョン・スタインソンとの共同研究は、新しいデータと新たな識別アプローチを重要な議論にもたらしました。

財政乗数を推定する際の重要な問題は、政府支出の真に外因性の変化を見つけることが難しいことです。 研究者たちは長い間、軍事的購買の変化が政府支出の外因性変動のもっともらしい候補であると主張してきた。 しかし、朝鮮戦争以来、総軍事支出に大きな変動はなかったので、総軍事支出は過去50年間の米国経済の政府支出倍率を特定するためには限られた用途しかない。 NakamuraとSteinssonの論文の重要な洞察は、全体として米国の軍事支出に大きな変動はなかったかもしれないが、地域の軍事支出にはかなりの変動があり、したがってこれらの地域の変動が政府支出倍率を推定するために使用できる。 これまでの研究におけるもう1つの重要な問題は、政府支出のアウトプット効果が(標準理論によると)金融政策の反応の性質に依存する可能性が非常に高いことです。 典型的な研究では、深刻な景気後退の間に政府が購入した結果生じる生産高のブームに対する典型的な金銭的反応によって生産高の影響がどの程度減少するのかを考慮していないことによって乗数を過小評価すると主張している。景気後退は(おそらく)全く異なるでしょう。 中村とシュタインソンの戦略は、金融政策の反応がすべての州に共通しているため、この問題を回避しているため、州間の産出に対する差異の影響を説明する要因となるべきではない。

政府支出の乗数を推定する際のさらなる複雑さは、その大きさが政府支出の変化に対する資金調達の仕方に左右されるということです。 これまでの研究では、資金調達上の考慮事項をどのように考慮に入れるかという問題がありました。 Nakamura and Steinssonの実証的戦略の利点は、地域の軍事支出が連邦税によって賄われているため、軍事支出の大部分を受け取る地域は軍事支出を受け取らない地域とは異なる税構造を持たないことです。 したがって、地域の軍事支出の変動を考慮し、それを地域の生産高変動と関連付けることで、以前の研究よりもはるかに信頼性の高い政府支出倍率の推定値が得られるはずです。

この論文は、政府による購入の乗数効果を測定するための賢い手段以上のものを提供しています。 著者らは、ある州における比較的高い購買がその州の相対的な経済活動に及ぼす影響の推定乗数が、政府の購買の全国的な増加の国内GDPへの影響の乗数と同じである必要はないと指摘する。いずれの州でも購買増加の影響が州間で波及しているため、「景気後退への対応としての「財政刺激」の有効性についての議論の中心的な論点である。 これらのスピルオーバーは、国家経済の開放性が低い一方で、ある州での所得の増加が州外供給業者からの購入の増加をもたらすだけでなく、ある州での相対的な政府支出の増加が国民の支出が増加する一方で、州の住民は合算で米国の納税者からの増収を要求されるでしょう。 SteinssonとNakamuraは、定量的な複数地域ニューケインジアン一般均衡モデルを開発し分析し、それらの推定値を説明することができるモデルパラメータ化の場合に国内乗数がどうなるかを尋ねることによって、2つの乗数の違いのありそうな大きさに対処する相対的な状態レベルの効果 この論文は、非構造的な経験的研究と推定から学ぶことができるものの慎重なモデルベースの分析とを組み合わせた、そしてマクロ経済政策にとってかなり重要な応用文献にかなりの貢献をする研究の優れた例を提供する。

中村はまた、金融政策の効果の実証分析にも重要な貢献をしてきました。 「貨幣的な非中立性の高頻度な識別:情報効果」(QJE、2018年、Steinssonとの共著)は、2000年1月から2014年3月までの間に予定されている106の連邦準備制度の発表を中心に30分の時間枠で金利の変化を研究している。関連文献の標準では、この30分の間に見られた金融市場の変化は、連邦準備制度理事会の発表で発表された情報に起因しています。 しかし、そのような金融政策への衝撃の「高頻度の識別」の初期の支持者とは異なり、NakamuraとSteinssonは明らかにされたニュースは与えられた経済的ファンダメンタルズに対する期待される金融政策の変化を表すだけではないと認識する。 それはまたFRBが認識しているが市場はまだ認識していなかったかもしれない経済の状態についてのニュース、またはFRBが発表の前に市場が信じていたものとは異なる経済の現状をどう解釈するかについてのニュースを含むことができます。 本稿の貢献は、そのような情報効果の存在の可能性を考慮しながら、金銭的な非中立性についての推論を引き出すことと、FRB発表の観測された効果を説明できる理論モデルを構築し推定することです。

この問題は、FRBの発表が情報効果と純粋な金融政策ショックの両方を持つ可能性があるモデルの開発に動機を与え、観察されたFRB発表の各要素がどれほど大きいかを推定することを可能にします。 この推定の結果は、提案されたモデルがFRB発表ショックの観測された影響をよく説明できることを示唆しています。 発表ショックの約3分の2が将来の経済的ファンダメンタルズに関するニュースを表しているため、純粋な金融政策のショックを表すのは3分の1に過ぎない。 そして、情報の影響が非常に重要であるにもかかわらず、FRBの発表に対する観察された対応は、米国経済における高度の金銭的非ニュートラルと一致しています。 これらは、貨幣経済学における根本的な疑問についての重要な結果であり、そしてこの論文は以前の方法論を大きく改善したものである。

Nakamuraの最も特徴的な貢献は実証的な研究に対するものでしたが、彼女の仕事は常に理論モデルの構造の高度な理解によって導かれ、そして彼女の貢献のいくつかは主に理論的なものです。 重要な例としては、彼女の論文「The Forward Guidanceの再考」( AER 2016、SteinssonとAlisdair McKay)があります。 本稿では、米国をはじめとする最近の金融危機に対する中央銀行の対応、すなわち将来の政策に関する中央銀行のコミットメントの程度(おそらくは現在の短期金利の水準に変化がない場合でも、金利が現在の水準にとどまることを示すことは、財務状況に影響を及ぼし、総需要を刺激する効果的な方法になります。

単純なニューケインジアンDSGEモデルは、将来的に順応性の高い政策を維持するという事前の約束が相当な刺激的効果をもたらすべきであることを示唆している。 実際、数年先まで続く低金利へのコミットメントの場合、モデルは経済活動とインフレの両方に対する直接的な影響を予測し、これを現実的な予測と見なすことは困難です。前向きな指導を伴う実際の実験のより控えめな効果と確かに一致しないもの。 これは「フォワードガイダンスパズル」と呼ばれています。中村と彼女の共著者は、完全な金融市場を仮定した結果として、各エージェントが単一の異時点間予算制約を持つという特徴に起因すると考えています。借入の制約はありません。 彼らは、代わりに決定不可能な所得リスクと借入制約の存在を考慮したモデルで固定名目金利に対する長期のコミットメントの効果を分析し、短期的な金融政策に対する期待の効果はそれらと類似しているがより単純なモデルによって予測されるように、固定名目金利に対する長期的なコミットメントの予測される効果ははるかに弱い。 本質的に、彼らは、借り入れ制約が結びつく次の数四半期にわたってある時点を持つ可能性がかなり高い世帯の場合、制約が結びつく時よりも未来の金融政策についての期待がそうであることを見出します。現在の支出能力には影響を与えず、これにより、将来の保険契約年数に関するコミットメントの現在の総需要に対する予測される影響が大幅に減少します。

したがって、彼らの代替モデルは、それが無関係であることをほとんど意味しないが、単純なモデルが意味するよりも、フォワードガイダンスが急激な収縮から抜け出すためのそれほど強力でないツールであることを意味する。 本稿は、重要な政策論議への貢献と、代替的な金融政策を評価するためのニューケインジアンモデルの適用に関する文献への有益な方法論的貢献の両方です。 それは所得の不均一性と借入制約を導入することのマクロ経済力学の他の側面への含意を探る「不均質エージェントニューケインジアンモデル」に関する活発な最近の文献を刺激しました。

中村は最近、Steinssonとの「マクロ経済学における識別」に関するJEPの記事と、過去数十年にわたって観察された景気後退からの緩やかな回復における女性の労働力参加の役割に関する新しいワーキングペーパーを発表しました。 前者は、彼女の財政政策書や価格設定書でも論じられているアプローチの興味深い一般化です。マクロ経済現象を特定するための断面積変動の使用と、慎重な構造モデリングによる総合的な影響の統制です。 このアプローチは、中村の最も影響力のある論文のいくつかに共通しており、方法論的に折衷的です。 それは、これだけでは彼女にとって興味のあるマクロ経済的な意味合いをもたらさないことを認識しながら、断面の変化を探るために新しいそしてより大きなデータセットの利用可能性における進歩を利用する。 マクロ的な意味では、ミクロデータの不均一性と平衡の考慮を考慮に入れた凝集のモデリングが必要です。 さらに、マクロモデルは、検証可能であり、競合するマクロ仮説を区別するための追加の規律と能力を提供する断面積に影響を与えます。 このアプローチは、住宅からの富の効果に関する最近のいくつかの論文でも適用されており、ミクロデータのみに焦点を当てた仕事とは大きく異なる意味合いをもたらしています。

景気後退からの緩やかな回復に関するワーキングペーパー「女性、富の効果、そして緩やかな回復」(FukuiとSteinsson)は、緩慢な回復現象が女性の労働力参加の男性への収束と同時に起こると述べている。 すなわち、20世紀半ばから20世紀後半にかけて女性の労働力参加が増加したため、女性が回復期間中に労働力に加わるにつれて、雇用は低迷から急速に回復した。 しかし、女性の労働力参加が上昇し、男性に集中するにつれて、その動きは薄れていった。 紙は、この効果だけで景気回復の鈍化の70%を占めると主張しています。 これは、興味深い「反対の数」の別の労働市場の発見です。企業は、解雇時により長期的な傾向に順応するため、景気後退時により早く調整するということです。 この結果は、新たな労働者を労働市場に引き込む能力がある場合には、上昇局面でも同様の知見を示唆しています。

中村の業績に対する事前の表彰には、NSFからのキャリア賞(2011)、AEAからのスローン研究フェローシップ(2014)、Elaine Bennett研究賞(2014)が含まれています。 IMF(2014)によって、そしてエコノミスト(2018)によって10年のトップ8若いエコノミストの一人に選ばれました。 彼女は、CBOの経済諮問委員会、国家統計に関するAEA委員会、およびBLS技術諮問委員会のAERの共編集者を務めています。 これらの任命は彼女がデータ構成に関する問題の専門家として専門職として彼女がすぐに得た役割を証明します。 経験的マクロ経済学の一般的な方法論、および金融および財政政策の影響を分析するための経験的根拠への彼女の貢献は、今年のジョンベイツクラークメダルの優れた候補者になります。

☆

水曜日、2019年5月1日

全体像を見て経済学者のための珍しい賞

ジョンクラークベイツメダルはほとんど決してマクロ経済学者に行きません。中村恵美は例外ではありません。

経済

によって

修正済み

勝者がいます。

写真家:Graham Morrison、ブルームバーグ/アメリカ経済協会

ジョンベイツクラークメダルは間違いなく経済学の分野で最も排他的な賞です。 ノーベル賞とは異なり、賞品は毎年1人のエコノミストにのみ与えられます(クラークメダルはアメリカ人だけのものですが)。 そしてそれを受け取るには40歳未満でなければなりません。 今年の賞は、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の中村恵美氏が受賞した、マクロ経済学の分野では議論の余地がありません。

ノーベルとは異なり、マクロ経済学者がクラークメダルを獲得することは稀です。 おそらく研究が主に景気循環を扱った最後の勝者は1993年にずっとずっと賞を受けたローレンスサマーズでした。少なくとも過去20年間、マクロ経済学は合意と漸進的な革新によって支配される分野である傾向がありました、傑出した天才はほとんどいない。 中村はまれな例外です。

中村は、ニューケインジアン経済学の分野におけるリーダーの一人です。 世界中の中央銀行で主流となってきたこの考え方は、金融危機や金利の大幅な上昇などのイベントに対応して企業が価格を調整できないために不況が発生すると考えています。 価格を調整する能力がなければ、理論は変わりません、企業は生産を減らし、代わりに労働者を解雇します。 共著者および夫の頻繁な共著者であるJon Steinssonの2008年の論文で、中村氏は、このいわゆる価格のこだわりがごくわずかであっても大きな不況を招き、経済を金融政策の変化に非常に敏感にすることを示した。

しかし、企業が価格を調整できないのは、まさに謎のままです。 中村の研究はこの問題を解明するのに役立ちました。 Steinsson に関する別の2008年の論文は、価格の粘着性がおそらく複数の要因から生じることを立証するのに役立ちました。

しかし、ニューケインジアン経済学の主要な光の一つとしての彼女の地位にもかかわらず、中村は考えに挑戦する彼女のキャリアの多くを費やしました。 Steinssonの最近の論文で、彼女は、標準ニューケインジアンモデル(および多くのマクロ経済学者の直感)が予測するものとは対照的に、金利の引き下げは期待インフレをそれほど上げずに将来の成長への期待を高める傾向があることを示した。 別の論文では、2人のエコノミストは、インフレが失業と同じくらい経済に害を与えるという多くのニューケインジアンモデルの仮定を疑問視した。

標準的なニューケインジアンモデルの最大の失敗は、彼らが中央銀行が金利を下げることによって不況と戦う能力を常に持っていると仮定することです。 名目金利がゼロをはるかに下回ることはできないため、最近の大不況はこのツールの限界を明らかにしました。 一部のエコノミストは、金利を引き下げる代わりに、中央銀行がフォワードガイダンス(つまり、景気後退が終わった後も金利を引き下げることを約束)を使用して、ほぼ同じ効果を得ることができると示唆しています。 しかし、Alisdair McKayとSteinssonと一緒に、中村は前方への指導のために大きな効果を予測する理論が非常に非現実的であることを示しました。

金利の引き下げやフォワードガイダンスが失敗した場合、不況と闘うために何ができるでしょうか。 最も強力な武器の1つは、政府支出プログラムによる財政刺激策かもしれません。 2011年、米国が再び経済成長に向けて奮闘し、政治家たちが大幅な予算削減を実現するかどうかを議論していたとき、中村とスタインソンは刺激の効果を測定する論文の 最初の版を発表しました 。 州間の軍事調達の違いを見て、エコノミストは地方自治体の支出の変化が地方経済をどのように押し上げたかを測定しました。 彼らの結論 - 1ドルの政府支出は約50セントの追加の私的経済活動を刺激した - は経済学の専門家の内部とそれ以外の両方に影響を及ぼした。

しかし、マクロ経済学はそれが不正確な科学であるということであり、中村やスタインソンのような非常によくできた論文でさえ、刺激が働くという疑いの影を超えて証明することはできません 。 そのため、マクロ経済学者はしばしば刑事のように行動し、さまざまな情報源からの統計的証拠の断片を集め、それらをまとまった絵にまとめる必要があります。 最近の調査報告で 、NakamuraとSteinssonは、マクロ経済学者が彼らが観察する相関関係が実際に因果関係を表しているということをより確信するために使用できる統計的アプローチを論じています。

このように、過去10年間にわたり、中村は経済学者が景気循環に関する理論と証拠を理解するのに多大な貢献をしてきました。 このリストでさえ、実際には彼女の貢献の完全な要約を提供していません。例えば、 最近の福井昌夫とSteinssonの論文で、彼女は女性の労働力への参入は男性をあまり混雑させなかったという証拠を示しました。 また、 住宅の経済学、 為替レート 、 中国の経済データのゆがみ、景気循環への不確実性の影響、および小売業者と卸売業者の関係についても研究しました。 超専門の時代に、中村は美徳として際立っています。

マクロ経済学は本質的に困難な主題であり、そこでは理論とデータの両方が非常に限られており、進歩は飛躍的ではなく少しずつ進歩する傾向がある。 しかし中村恵美の貢献は、マクロ経済学に取り組むトップの精神がまだあることを示しています。 結果として、世界はより良くなるでしょう。

( Lawrence SummersがJohn Bates Clark Medalに勝った最後のマクロ経済学者であったことを示すために2段落目を訂正します。 )

このコラムは、編集委員会またはブルームバーグLPとその所有者の意見を必ずしも反映するものではありません。

A Rare Prize for an Economist Looking at the Big Picture

The John Clark Bates Medal almost never goes to a macroeconomist. Emi Nakamura is a worthy exception.

Economics

By

Corrected

We have a winner.

Photographer: Graham Morrison, Bloomberg/American Economic Association

The John Bates Clark medal is arguably the most exclusive award in the field of economics. It’s given to only one economist each year — unlike the Nobel prize, which often is shared among several (though the Clark medal is only for Americans). And one must be under age 40 to receive it. This year’s prize goes to Emi Nakamura of the University of California-Berkeley, an undisputed star in the field of macroeconomics.

Unlike the Nobel, it’s rare for a macroeconomist to get the Clark medal. Arguably the last winner whose research dealt mainly with the business cycle was Lawrence Summers, who received the prize all the way back in 1993. For at least the past two decades, macroeconomics has tended to be a discipline ruled by consensus and by incremental innovations, with few standout geniuses. Nakamura is a rare exception.

Nakamura is one of the leaders in the field of New Keynesian economics. This school of thought, which has become the dominant paradigm at central banks around the world, holds that recessions happen because companies are unable to adjust their prices in response to events like a financial crisis or a big rise in interest rates. Without the ability to adjust prices, the theory goes, companies cut their output and lay off workers instead. In a 2008 paper with frequent co-author and husband Jon Steinsson, Nakamura showed that even very small amounts of this so-called price stickiness can generate large recessions, and make the economy very sensitive to changes in monetary policy.

Exactly why companies can’t adjust prices, however, remains something of a mystery. Nakamura’s research has helped to shed light on this question. Another 2008 paper with Steinsson helped to establish that price stickiness probably results from multiple factors.

But despite her status as one of the leading lights of New Keynesian economics, Nakamura has spent much of her career challenging the idea. In a recent paperwith Steinsson, she showed that interest rate cuts tend to boost expectations of future growth without raising expected inflation much — in contradiction of what standard New Keynesian models (and the intuition of many macroeconomists) would predict. In another paper the two economists questioned the assumption of many New Keynesian models that inflation causes as much harm to the economy as unemployment.

The biggest failure of standard New Keynesian models is that they assume a central bank always has the ability to fight recessions by lowering interest rates. The recent Great Recession exposed the limits of this tool because nominal interest rates can’t go much below zero. Some economists have suggested that in lieu of cutting rates, central banks could use forward guidance — that is, promising to keep rates lower for longer even after the recession ends — to much the same effect. But together with Alisdair McKay and Steinsson, Nakamura showed that theories that predict big effects for forward guidance are highly unrealistic.

If interest rate cuts and forward guidance fail, what can be done to fight recessions? One of the most potent weapons might be fiscal stimulus via government spending programs. In 2011, as the U.S. was struggling to get its economy growing again and politicians were debating whether to enact deep budget cuts, Nakamura and Steinsson came out with the first version of a papermeasuring the effects of stimulus. Looking at differences in military procurement across states, the economists measured how changes in local government spending boosted local economies. Their conclusion — that each dollar of government spending stimulated about 50 cents of additional private economic activity — was influential both within the economics profession and outside of it.

But macroeconomics being the inexact science that it is, even very well-done papers like Nakamura and Steinsson’s can’t prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that stimulus works. That’s why macroeconomists often have to act like detectives, gathering shreds of statistical evidence from a variety of sources and aggregating them into a coherent picture. In a recent survey paper, Nakamura and Steinsson discuss statistical approaches that macroeconomists can use to be more confident that the correlations they observe really represent causation.

Thus, over the past decade, Nakamura has contributed a vast amount to economists’ understanding of the theory and evidence regarding business cycles. Even this list doesn’t really provide a full summary of her contributions — for example, in a recent paper with Masao Fukui and Steinsson, she showed evidence that women’s entry into the labor force hasn’t crowded out men very much. She has also done work on the economics of housing, exchange rates, distortions in Chinese economic data, the impact of uncertainty on the business cycle, and the relationships between retailers and wholesalers. In an age of hyper-specialization, Nakamura stands out as a virtuoso.

Macroeconomics is an inherently difficult subject, where theory and data are both extremely limited and progress tends to proceed in small increments rather than leaps and bounds. But the contributions of Emi Nakamura show that there are still top minds working in macroeconomics. The world will be better off as a result.

(Corrects second paragraph to indicate that Lawrence Summers was the last macroeconomist to win to John Bates Clark Medal.)

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

UP NEXT

Fed’s Powell Snatches Defeat From the Jaws of Victory

中村恵美

中村恵美さんは、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校 経済学部長、 [1] 国立経済研究局の研究員であり、 American Economic Reviewの共同編集者です。 [2]彼女はジョンベイツクラーク勲章 [3]を授与され、2019年にアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーに選出された。彼女はNSFキャリアグラントとスローン研究フェローシップを授与され、 エレインベネット研究賞を受賞した。 、 [4] [5]そして、 IMFによって2014年に45歳未満のトップ25のエコノミストの一人に選ばれました。 ハーバード大学で経済学博士号を、プリンストン大学で修士号を取得した[7] 。

彼女の研究は、 価格の粘着性 、 財政ショックの影響、公式統計の測定誤差など、 マクロ経済学における経験的な問題に焦点を当てています。 特に影響力のある仕事で、彼女は多くの測定された価格変化が経済状況への動的な反応として起こるのではなく、はるかに前もって予定されている一時的な販売によるものであることを示した。 [8]

彼女は同僚のエコノミスト、Jon Steinssonと結婚し[9] 、エコノミストのAlice NakamuraとMasao Nakamuraの娘[10] [11]とエコノミストのGuy Orcuttの孫娘である。

Contents

選んだ作品

インフレと価格の変動

中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon(2008)。 「価格に関する5つの事実:メニューコストモデルの再評価」。 季刊経済ジャーナル 。 123 (4):1415 - 1464。 JSTOR40506213 本稿では、詳細なミクロ経済価格データを分析し、価格の粘着性のメニューコストモデルをテストするための企業の価格設定行動について説明します 。 彼らは複雑な証拠を見つけます。データ内のいくつかの事実はメニューのコストモデルと一致していますが、そうではありません。

中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon。 太陽、パトリック。 Villar、Daniel(2018)。 「とらえどころのないインフレコスト:米国のグレートインフレの間の価格分散」 (PDF)季刊経済ジャーナル 。 133(4):1933-1908。 インフレのコストを測定しようとします。 一般的に使用されているニューケインジアンのマクロ経済モデルでは、インフレの社会的コストは非効率的な物価の分散から発生します。 中村ら。 この仮説を検証するために、1970年代と1980年代の米国の高インフレ時代の価格データをデジタル化します。彼らは「物価変動の絶対サイズがグレートインフレの間に上昇したという証拠はない」と結論付け、「これはインフレの厚生費の標準的なニューケインジアン分析が間違っていることを示唆している。再評価 "#:。

金融政策

中村恵美(2018)。 「貨幣の非中立性の高周波識別:情報効果」 (PDF) 季刊経済ジャーナル 。 133(3):1283-1330。 連邦準備制度の金利発表後30分のウィンドウで、実質変数(実質金利、経済成長率)に対する金融市場の期待の変化を示しています。

McKay、Alisdair。 中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon(2016)。 「フォワードガイダンスの力の再検討」 (PDF) アメリカ経済レビュー 106(10):3133−3158。 金融市場が不完全な場合、具体的には、エージェントが借入の制約や不可解な所得リスクに直面した場合、フォワードガイダンスの影響は大幅に減少する可能性が高いと主張しています。

中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon(2010)。 「マルチセクターメニューのコストモデルにおける通貨の非中立性」 季刊経済ジャーナル 。 125(3):961-1013。 JSTOR 27867504

財政方針

中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon(2014)。 「通貨同盟における財政刺激策:米国地域からの証拠」。 アメリカ経済レビュー 104 (3):753−792。 JSTOR 42920719 。 米国の軍事支出の地域的変動を用いて、1.5の「開放経済乗数」を推定している。 この実証的証拠は、「需要ショックが生産高に大きな影響を及ぼし得ることを示唆している」とくに特に下限がゼロの場合にそうである。 [12]

経済危機

中村、エミ。 Steinsson、Jon。 バロ、R。 Ursúa、J(2013)。 「消費災害の経験的モデルにおける危機と回復」 (PDF) アメリカ経済ジャーナル:マクロ経済学 。 5 (3):35–74。

参照

- ^ "中村恵美のCV" (PDF) 。

- ^ 「アメリカの経済連合」 。 www.aeaweb.org 2018-08-28を取得しました 。

- ^ 「アメリカの経済連合」 。 www.aeaweb.org 2019-05-01を取得しました 。

- ^ 中村恵美2014年エレインベネット研究賞受賞 。 アメリカ経済協会。 aeaweb.org

- ^ "中村恵美さんがAEAのエレイン・ベネット研究賞を受賞| Columbia University - Economics" 。 econ.columbia.edu 2017-08-07を取得しました 。

- ^ "NBERレポーター2015年第1号:研究概要" 。 www.nber.org2017-08-07を取得しました 。

- ^ 総務、公共。 11月14日、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校|; 2018 12月10日。 2018(2018−11−14)。 「私たちの新しい教員に会いましょう:中村恵美、経済学」 。 バークレーニュース 。2019-04-18を取得しました 。

- ^ "インタビュー:中村恵美" (PDF) 。 エコフォーカス - リッチモンド連邦準備銀行の出版物 。 2015年

- ^ Rampell、Catherine(2013-11-05)。 「成功への道をアウトソーシングする」 。 ニューヨークタイムズ ISSN 0362-4331 。2017-08-07を取得しました 。

- ^ "中村恵美とのインタビュー" 。 CSWEPニュース 2015年

- ^ CSWEPトーク 。 aeaweb.org

- ^ 中村、えみ。 Steinsson、Jón(2011-10-02)。 「財政刺激策は通貨同盟で働くのか?米国地域からの証拠」 。 VoxEU.org 。2019-04-18を取得しました 。

Emi Nakamura

Emi Nakamura is Chancellor's Professor of Economics at University of California, Berkeley, a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research,[1] and a Co-Editor of the American Economic Review.[2] She was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal[3] and elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2019. She has been awarded an NSF Career Grant and Sloan Research Fellowship, was the 2014 recipient of the Elaine Bennett Research Prize,[4][5] and was named one of the top 25 economists under 45 in 2014 by the IMF.[6] She received her PhD in Economics from Harvard and her AB from Princeton[7].

Her research focuses on empirical issues in macroeconomics, including price stickiness, the impact of fiscal shocks, and measurement errors in official statistics. In particularly influential work, she showed that many measured price changes are due to temporary sales, scheduled far in advance, rather than happening as dynamic responses to economic conditions.[8]

She is married to fellow economist Jon Steinsson,[9] and is the daughter of economists Alice Nakamura and Masao Nakamura[10][11] and the granddaughter of economist Guy Orcutt.

Contents

Selected works

Inflation and price dispersion

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2008). "Five facts about prices: A reevaluation of menu cost models". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 123 (4): 1415–1464. JSTOR 40506213. This paper analyzes detailed microeconomic price data and describes firms' price-setting behavior to test the menu cost model of price stickiness. They find mixed evidence: some facts in the data are consistent with the menu cost model, but others are not.

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon; Sun, Patrick; Villar, Daniel (2018). "The Elusive Costs of Inflation: Price Dispersion during the U.S. Great Inflation" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 133(4): 1933–1908. attempts to measure the costs of inflation. In the commonly used New Keynesian macroeconomic models, the social costs of inflation arise from inefficient price dispersion: higher inflation implies higher price dispersion. Nakamura et al. digitize price data from the era of high inflation in the US in the 1970s and 1980s to test this hypothesis. They find "no evidence that the absolute size of price changes rose during the Great Inflation", and conclude that "This suggests that the standard New Keynesian analysis of the welfare costs of inflation is wrong and its implications for the optimal inflation rate need to be reassessed".

Monetary policy

Nakamura, Emi (2018). "High-Frequency Identification of Monetary Non-Neutrality: The Information Effect" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 133(3): 1283–1330. demonstrates changes in financial market expectations of real variables (the real interest rate, and economy growth) in the thirty-minute window after Federal Reserve rate announcements.

McKay, Alisdair; Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2016). "The Power of Forward Guidance Revisited" (PDF). American Economic Review. 106(10): 3133–3158. argues that the effects of forward guidance are likely to be substantially reduced if financial markets are incomplete: specifically, if agents face borrowing constraints and uninsurable income risk.

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2010). "Monetary non-neutrality in a multisector menu cost model". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 125 (3): 961–1013. JSTOR 27867504.

Nakamura, Emi; Zerom, D (2010). "Accounting for incomplete pass-through". The Review of Economic Studies. 77 (3): 1192–1230. JSTOR 40835861.

Fiscal policy

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon (2014). "Fiscal stimulus in a monetary union: Evidence from US regions". The American Economic Review. 104 (3): 753–792. JSTOR 42920719. uses regional variation in US military spending to estimate an "open economy multiplier" of 1.5. This empirical evidence "indicates that demand shocks can have large effects on output", particularly at the zero lower bound.[12]

Economic crises

Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jon; Barro, R; Ursúa, J (2013). "Crises and recoveries in an empirical model of consumption disasters" (PDF). American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 5 (3): 35–74.

References

- ^ "C.V. of Emi Nakamura" (PDF).

- ^ "American Economic Association". www.aeaweb.org. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ^ "American Economic Association". www.aeaweb.org. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- ^ Emi Nakamura Recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize. American Economic Association. aeaweb.org

- ^ "Emi Nakamura Receives AEA's Elaine Bennett Research Prize | Columbia University - Economics". econ.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- ^ "NBER Reporter 2015 Number 1: Research Summary". www.nber.org. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- ^ Affairs, Public; November 14, UC Berkeley|; 2018December 10; 2018 (2018-11-14). "Meet our new faculty: Emi Nakamura, economics". Berkeley News. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ "Interview: Emi Nakamura" (PDF). Econ Focus--A publication of the Richmond Federal Reserve Bank. 2015.

- ^ Rampell, Catherine (2013-11-05). "Outsource Your Way to Success". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- ^ "An Interview with Emi Nakamura". CSWEP News. 2015.

- ^ CSWEP Talks. aeaweb.org

- ^ Nakamura, Emi; Steinsson, Jón (2011-10-02). "Does fiscal stimulus work in a monetary union? Evidence from US regions". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

NAMS出版プロジェクト

HTTP://WWW.FREEASSOCIATIONS.ORG/

水曜日、2019年5月1日

優等賞/ベイツクラーク/エミ・ナカムラ

中村恵美、クラークメダリスト2019

アメリカ経済協会名誉賞委員会

2019年4月

2019年4月

中村恵美は経験的なマクロ経済学者で、企業による価格設定と金融政策や財政政策の影響についての理解を大いに高めました。 中村の独特のアプローチは、マクロ経済学における長年の疑問に取り組むための新しいデータ源を提案するというその創造性のために注目に値する。 彼女が使用しているデータセットは、経験的マクロ経済学におけるこれらのトピックに関するこれまでのほとんどの研究の基礎となっていた戦後の四半期ごとの時系列よりも、より分離されていない、より高い頻度で、あるいはより長い歴史的期間にわたって伸びています。 彼女の研究は、以前には利用されていなかったデータソースの骨の折れる分析を必要とし、同時にデータを区別するために使用することができる代替の理論モデルの高度な理解を示しています。

中村は、個々の製品の価格に関するミクロ経済データを使って、マクロ経済文献で使われている価格設定モデルの経験的妥当性について結論を出すことで最もよく知られています。 これは、金融政策の短期的影響を分析する上で重要な問題となっています。 個々の物価の調整、特に物価が変化しないことが観察される平均時間の尺度に関する研究は、物価の硬直性の重要性に関する長い証拠となりました。 しかし、ごく最近まで、この種のほとんどの証拠は非常に少数の市場の研究から来ていたので、これらの特定の価格がどれほど典型的であるかという問題は依然として重要な制限であった。 非常に多数の商品の価格の変化を同時に追跡することを可能にする新しいデータセットの利用可能性は、過去15年間にわたってこの文献を根本的に変革しました、そして中村は彼女の頻繁な共著者JónSteinssonと共にプレーしましたこの開発における主導的役割。

彼らの最も引用されている論文「価格に関する5つの事実:メニューコストモデルの再評価」( QJE 2008)では、中村とSteinssonは、米国の公表消費者物価指数と生産者物価指数の構築に使用される個々の価格に関するBLSデータを研究します。これは、一般的な価格調整の理論モデルである「メニューコスト」モデルの意味と比較することができます。 彼らは、物価変動の平均頻度、すなわち金融政策の効果の定量的モデルの数値校正における重要な問題に特に注意を向けています。 他の情報源を使った過去の研究では、米国経済の価格変動間の時間の中央値はほぼ1年であると結論づけられていましたが、BLSマイクロデータ(Mark BilsとPete Klenowによる)を使った最初の研究は、実際には、価格はずっと頻繁に変化しました(期間の中央値は4ヶ月強に過ぎません)。 BilsとKlenowは、実際にはBLSマイクロデータセットを使用していませんでしたが、1995年から1997年までの期間の値からの抜粋で、非常に細分化されたレベルでの価格変動の平均頻度を報告しました。 中村とSteinssonは代わりにBLSによって使われた実際のミクロデータへのアクセスを得ました、そしてそれはBLSによってそして1988年から2005年までの期間の間に集められたすべての価格観察を持っています。

NakamuraとSteinssonは、優れたデータセットを使用してBilsとKlenowの結論を再考すると、CPIデータの価格変動の頻度に関する結論は、売上を「通常価格」の変動と区別するための方法によって異なることを示しています。卸売価格と消費者価格 彼らは、通常の価格の変更が売上を含む価格の変更よりもはるかに少ない頻度で発生することを発見します(彼らは価格変更を分類するために使用される正確な方法に応じて、通常の価格の中央値8-11ヶ月を見つけます)。 「売上」を除外する必要がほとんどない場合も、ほとんど変わりません。 この論文がそれほど影響力を持っている最初の理由は、BilsとKlenowの驚くべき結果が暗示していたよりもはるかに実質的な個々の価格の「粘着性」について非常に説得力のあるミクロ経済的証拠を与えることです。 このペーパーは、特定のモデルの価格調整モデルの現実性をテストするために使用できる個々の価格変更に関するデータの機能を文書化するのにも役立ちます。NakamuraとSteinssonは、価格調整モデルの一般的なクラス(「メニューコスト」または「Ss」モデル)の予測に反するデータの2つの特徴を強調しています。価格のハザード関数は、最後の価格変更以降の時間で増加します。

価格変動に関するミクロデータの量的特性を説明するための「メニューコスト」モデルの能力については、「マルチセクターメニューコストモデルにおける貨幣の非中立性」( QJE 2010、Steinssonも同様)でさらに検討されている。 メニューコストモデル(GolosovとLucasによる影響力のある論文のような)の意味の以前の数値分析は、経済のすべての商品が同じサイズのメニューコストの影響を受けると仮定していた(同じ技術で生産されることに加えて)すべての商品に共通のパラメータには、すべての価格変動のセットの統計と一致するように数値が割り当てられています(価格変動の全体的な頻度および価格変動の平均絶対サイズなど)。 しかし、「5つの事実」でNakamuraとSteinssonによって文書化された事実の1つは、非販売価格の変化の頻度において米国経済の部門間で途方もない異質性があるということです。

“ Monetary Non-Neutrality”の論文では、価格変動の頻度と価格変動の平均サイズの両方の部門間の分布にも一致するように、複数部門のメニューコストモデルを調整しています。 彼らは、金銭的混乱の実際の影響は、(GolosovやLucasのような)1セクターモデルの場合と比べて、すべての企業の平均価格変動頻度に合わせて調整した場合の3倍になっていることを見出しました。 確かに、GolosovとLucasは物価の硬直性が金銭的混乱の観察された影響についての経験的にもっともらしい説明ではないと主張する一方、中村とSteinssonは彼らの較正されたマルチセクターモデルを示す(米国経済に見られる規模の名目上のショックで)は、米国の景気循環のほぼ4分の1を占めるであろう生産高の変動を予測する。 これは、理論的ベクトル自己回帰研究における金銭的攪乱に起因するGDPの変動性の割合とおおまかに一致します。 価格の粘着性の程度をパラメータ化する際に部門別の異質性を考慮に入れることの重要性に対するこの論文の強調は、非常に影響力があります。

最近では、NakamuraとSteinssonは消費者物価に関するBLSミクロレベルデータセットを1977年まで拡張することにかなりの努力を注いできました。 1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけて、1988年以来、インフレ率がはるかに高く、変動しやすくなりました。拡張データセットを利用した最初の論文は、Patrick SunとDaniel Villarによるものです。インフレ」( QJE、近日発表予定)。 本稿は、変化する市況に対する自社の価格の調整が、インフレ率の高い環境でどのように異なるかを考察しています。 著者らは、「通常の」(すなわち、非販売)価格は、彼らのデータセットの初期(インフレ率が高い)部分でより頻繁に調整され、最適価格調整のモデルによって予測される金額で会社の価格を調整するための固定費(「メニュー費用」)。 彼らは、このことから、恒久的に高いインフレ率を選択することから生じると予想される厚生費用を評価する際には、価格の変動を回避しつつ、発生すると予想される価格調整の頻度の増加を考慮することが重要であると結論する。そうでなければ、よりインフレの高い環境で予想されるように、現在の状況と一致

本稿はまた、インフレ率が高い環境において、類似製品の価格にどの程度のばらつきがあるかを測定しようとしている。 価格調整の一般的なモデルには、次のようなものがあります。さまざまな企業の価格が再考される時期がずれると、最適な価格は週ごとの価格の上昇率によって異なります。 。 もしそうであれば、これはインフレ率の高い環境における資源配分の歪みの増大の重要な原因となるはずである。 真に同一の商品の価格のばらつきの程度を測定することは困難です。なぜなら、異なる企業の商品の異なる価格は商品の不均一性を反映し、完全に柔軟な価格であっても異なる価格を持つからです。

このため、著者らは代わりに、物価変動の平均規模(物価調整時)が高インフレ期間と低インフレ期間の間でどのように異なるかを調べることを提案している。 アイデアは、価格が変更されるたびに現在の最適レベルに調整される場合、観測される価格変更のサイズは、価格が調整前の最適レベルからどれだけ離れているかを示します。 彼らは、発生した場合の平均価格上昇幅は、1988年以前のサンプルでも1988年後のサンプルとほぼ同じである(平均で7%の増加)ことを発見しました。 繰り返しになりますが、彼らはこれを物価変動のタイミングが独立している場合に予想されるものと比較してインフレによって生じる歪みを減らすように、物価変動のタイミングが内在的に調整する証拠として解釈します特定の会社の価格が現在の市況と一致しなくなった程度。 著者らは、慢性的に高いインフレの厚生費用は、外因的な価格調整の頻度を伴うスティッキープライスモデルに基づく厚生計算ほど大きくはないかもしれないと結論付けている。 紙は同時にインフレのコストについての政策論争への重要な貢献である。 米国における価格調整に関する歴史的事実の理解 そして価格設定の代替理論モデルの現実性を評価するための経験的根拠に。