Stephanie Kelton For President

Irrespective of what happens from here in the Sino-US trade dispute, investors believe the damage to the global economy is done.

Trade uncertainty is probably here to stay, as is populist politics in one form or another.

Central banks were already constrained in their capacity to rescue the world, and persistent trade uncertainty makes it mission impossible with rates already so close to the lower bound.

Ironically, populism may have the solution for the economic malaise that was in part precipitated by protectionism run amok.

Here's a look at the nexus between trade wars, monetary policy at the limits and the current political environment.

By 9:30 a.m. in New York on Monday, sentiment around the "Phase One" trade "deal" announced during a glorified Oval Office photo op on Friday afternoon had deteriorated so much that Global Times editor Hu Xijiin (whose tweets are generally seen as Party pronouncements) had to step in.

"Based on what I know, China-US trade talks made [a] breakthrough last week and the two sides have the strong will to reach a final deal," Hu said, adding that although the "initial statement of the Chinese side is moderate... it doesn't mean China's real attitude is not positive."

Hu was clearly responding to a Bloomberg sources story which suggested that Beijing is already seeking another round of talks before anything is finalized with regard to the nebulous agreement unveiled in Washington late last week. I documented the "deal" in a Friday evening post for readers here. Suffice to say that in the 48 hours since, the sellside hasn't been able to divine anything above and beyond what was mentioned by President Trump at the White House.

To give you an idea about the general tone across desks as it relates to the "Phase One" agreement, Goldman called it " fairly straightforward [in] certain aspects," which sounds like a euphemistic way of saying "clear as mud."

I'm editorializing there - the bank was pretty charitable in their brief assessment delivered in a Saturday note, but the point is simply that the President and Chinese Vice Premier Liu He didn't give market participants much to chew on, probably because not much was actually accomplished beyond China committing to ramp up farm purchases. Here's an excerpt from a BofA note out Sunday:

What we don’t know..? A lot, but watch the markets. A lot of details are still missing and much still needs to be agreed upon such as China subsidies and support to SOEs, enforcement mechanisms. The tone from China is cautious and government media news agencies still characterize the situation as facing many uncertainties, but have called the deal rational and pragmatic. However, they have not confirmed whether President Xi will sign the deal at the November APEC Summit. This paradox of known knowns and remaining unknowns is reflected in markets.

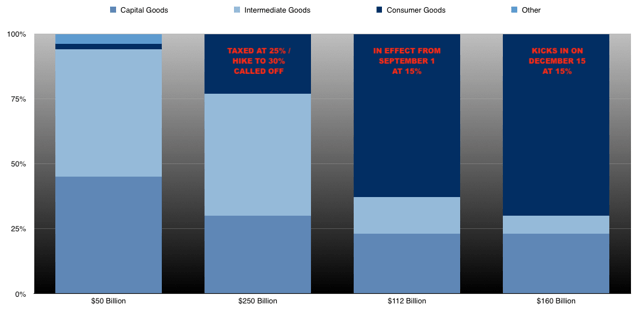

Steve Mnuchin on Monday morning told CNBC that barring further progress between now and then, 15% tariffs on $160 billion in additional Chinese goods will still go into effect on December 15. That's a source of consternation for markets and also for Beijing which, according to Bloomberg's reporting, wants that threat taken off the table. Here's an updated breakdown of the tariffs vis-à-vis China:

Note that in addition to being skewed towards consumer goods (which is obviously a problem for a US economy that's now running almost solely on the consumer) the timing of the December escalation coincides with the last FOMC meeting of the year.

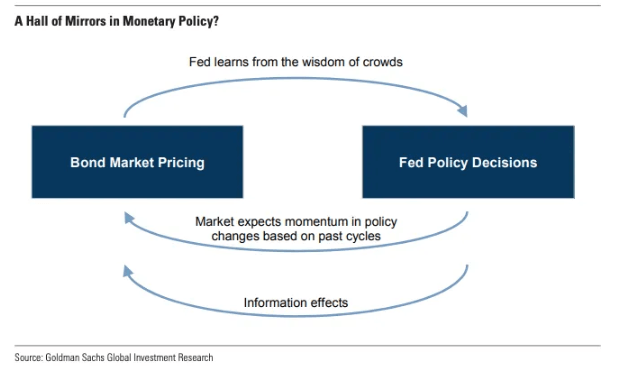

I've mentioned this previously, but it bears repeating: Donald Trump's primary source of leverage over Fed policy is his ability to engineer rate cuts with tariff escalations. The reason he has been so "successful" (if that's how you want to frame things) in that regard has more to do with market pricing than it does with business uncertainty. A recent study by Goldman found that Trump's trade tweets were far more impactful at moving market pricing towards additional Fed cuts than tweets about monetary policy itself. When market pricing moves in that direction, it corners the Fed. Here's why (via a July Goldman note):

It starts from the observation that Fed officials now seem to put greater weight on bond market pricing in making monetary policy decisions than in the past, partly because they worry more about the consequences of disappointing market expectations for cuts and partly because some of them put a significant amount of weight on bond market signals in gauging the outlook for growth and inflation. This can lead to a positive feedback loop between more dovish bond market pricing and more dovish central bank decisions. This feedback loop might not be broken until the economic data signal very decisively that further easing is inappropriate.

As to whether President Trump understood that in July of 2018 when he began to criticize the Jerome Powell Fed just as the trade war got going in earnest, you can color me skeptical.

But, the President has doubtlessly figured it out. Indeed, he's now an expert in playing the game. How many times, over the past six months, have you heard Peter Navarro and Larry Kudlow tell CNBC, Bloomberg and Fox Business that the "market thinks Trump is right on the Fed" (or some riff on that general theme)? They have said that on too many occasions to document, and that's indicative of the extent to which the White House is using the dynamic described above by Goldman to their advantage.

I do not believe that the President would (or even "should") give up that leverage by taking the December tariff escalation off the table with China.

The reference to "should" is just me looking at things from a strategic perspective. From a normative perspective, all of these tariffs should be lifted, because they are deep-sixing the global economy. Both the IMF and the OECD project the slowest pace of growth since the crisis in 2019. In their latest update, the OECD was emphatic. Here's an excerpt from a scathing assessment by OECD chief economist Laurence Boone:

The proliferation of tariffs and subsidies and the increasing unpredictability of trade policies have destroyed growth in international trade, triggering a sharp slowdown in industrial output and investments. When companies do not know what tomorrow will bring, they exercise their “wait-and-see option”. Given that an investment is a long-term commitment, they are waiting for this insidious trade war to settle down in order to know where to invest. However, when temporary uncertainty is recurrent and rooted, large amounts of investments are withheld, thereby affecting not just present day demand but also tomorrow’s growth potential and employment.

The problem now is that even if the US and China were to miraculously strike a comprehensive deal that removes all tariffs and non-tariff barriers immediately, it would be too late - not necessarily too late to avert a catastrophe, but certainty too late to avoid a deepening of the current global slump.

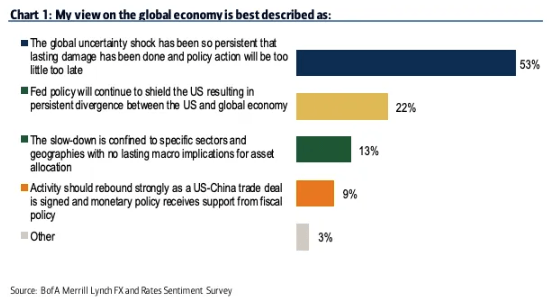

If you don't believe me (or the IMF or the OECD), just ask the 57 fund managers across multiple continents who participated in the latest edition of BofA's FX and rates sentiment survey. Asked to choose from a variety of statements regarding the prospects for the flagging global economy, respondents overwhelmingly chose "The global uncertainty shock has been so persistent that lasting damage has been done and policy action will be too little, too late."

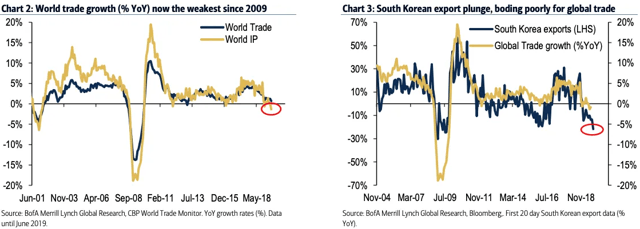

(BofA)

(BofA)

Together, the participants in the survey control more than $800 billion in AUM.

Obviously, the plunge in global bond yields in 2019 telegraphed something about the outlook for growth and inflation, although it shouldn't be lost on readers that the plunge in long-end Treasury yields in August was at least partially attributable to hedging flows. The same BofA survey mentioned above found 55% of respondents saying a fundamental reassessment of the global growth and inflation outlook has been the driving force behind the rates rally.

It seems unlikely that trade tensions are going to abate entirely anytime soon. Indeed, the US on Monday got the final green light from the WTO to impose tariffs on Europe in the long-running dispute over Airbus subsidies. A parallel case involving Boeing is expected to be adjudicated early next year, at which point Brussels will likely retaliate, although Europe continues to beg Washington to reconsider.

There is virtually no chance that the structural issues at the heart of the Trump administration's dispute with China will ever be resolved once and for all. Indeed, if you read Elizabeth Warren's trade plan, it is entirely possible to argue that although Warren would likely be easier for other nations to deal with on a personal basis, her actual terms would be even more onerous than Trump's. You can probably make a similar argument with regard to Bernie Sanders.

With monetary policy having reached the apparent limits of its effectiveness, this all makes for a rather vexing quandary. BofA's Barnaby Martin (he's technically head of the bank's European credit team, but his weekly notes are expansive in terms of topics addressed) recently warned that trade uncertainty poses a "daunting headwind" to new QE in Europe. Implicit in his take was that monetary easing the world over is being hamstrung not just by mechanical constraints associated with the lower bound for rates and the various operational and political hurdles to more asset purchases, but by persistent and seemingly intractable trade frictions.

Global trade volumes, he wrote, "are now contracting at their fastest rate since late 2009" and, worryingly, that's unfolding at a time when world GDP growth is still positive. That juxtaposition is a relative rarity over the last two decades.

For Martin, the future is what he calls "public-private policy partnerships," wherein QE effectively frees up governments to borrow.

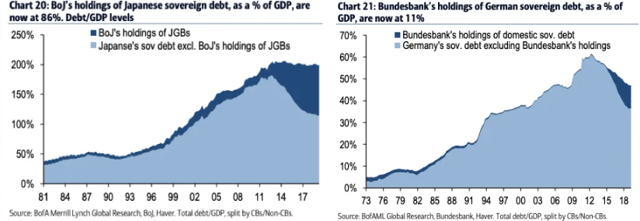

I've been over this before (both here and elsewhere) but it bears repeating ad nauseam. "If QE is sizable enough, the transformation in debt-to-GDP ratios can be meaningful," Martin wrote in a separate note last month. Have a look at the following two charts which illustrate the point:

The idea is that as central banks onboard government debt, it theoretically de-risks the market, reducing the odds of tantrums, and making "higher sovereign debt levels attainable," to quote BofA.

Of course, there's a (compelling) argument to be made that the more beholden a given government bond market is to the central bank, the higher the tantrum risk given that market functioning becomes impaired as ownership becomes more concentrated in the hands of the benefactors with the printing presses.

That rather important caveat aside, though, the thrust of this is that monetary policy will eventually become an extension of fiscal policy, as politicians borrow to finance ambitious agenda items in a world where the old "rules" (e.g., the Phillips curve) no longer apply.

If that sounds like central banks directly financing spending by their own governments, that's because it is and, increasingly, it's seen as the only arrow left in the quiver when it comes to reviving moribund inflation and engineering robust growth.

This is the ultimate irony of populism both on the left and right.

The protectionist bent on trade and the policy prescriptions which generally accompany a narrative that revolves around rescuing "our" workers and "our" industries and "our" middle class (that narrative is shared by President Trump, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders), are detrimental to global growth in a world that has, for decades, run on the assumption that globalization would continue apace, making markets and supply chains ever more interconnected and borders less and less relevant.

But, paradoxically, populism also has what might be the only viable prescription when it comes to making a serious run at reviving global growth and engineering robust expansions. That prescription involves pairing monetary policy with fiscal stimulus in MMT-esque fashion ("MMT" is, of course, the acronym for Modern Monetary Theory). Here's BofA's Martin one more time:

In fact, low rates and QE will become essentials in helping governments create ‘fiscal space’ and manage the transition to higher debt levels. At the extreme [they may] participate in ideas such as MMT, in our view.

You're reminded that while the likes of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are the politicians most associated with MMT in the US, Donald Trump is arguably implementing it in real-time, on Twitter. This might rub some readers the wrong way, but the fact of the matter is that when you are issuing debt to finance tax cuts while simultaneously demanding the central bank cut rates to zero and restart QE (as the President has explicitly done on dozens of occasions), you are by definition calling for MMT, albeit a kind of perverse, supply-side variant.

My good buddy Kevin Muir (formerly head of equity derivatives at RBC Dominion and currently head of research at East West Investment Management and the author of The Macro Tourist) has called Trump "the first MMT president."

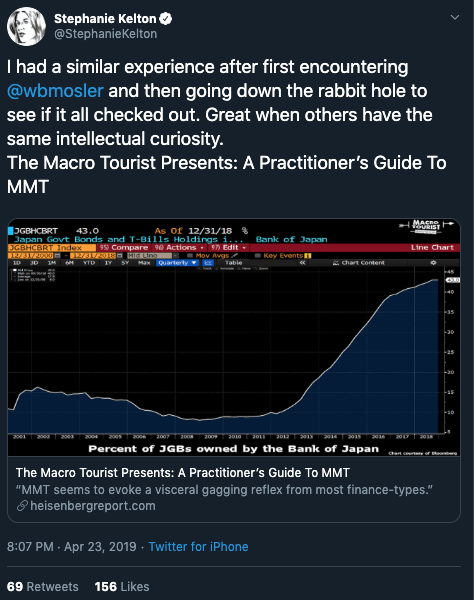

For what it's worth, Kevin and I are at least somewhat credible on this subject. After all, Stephanie Kelton herself (the patron saint of MMT and Bernie Sanders's senior economic advisor) tweeted the following back in April:

Where does all of the above leave investors going forward?

Where does all of the above leave investors going forward?

Well, it leaves market participants facing what is becoming an increasingly binary set of outcomes.

One one hand, it's possible that western politics suddenly pivots away from the extremes and centrists reclaim the narrative, ushering in a return of what, until 2015, was the status quo.

That doesn't seem likely.

If you assume that centrist politics will be on the back foot for years to come as right- and left-wing populists battle for votes, then I would argue that trade tensions are going to be the "new normal." When it comes to offsetting the deleterious growth effects of a more inward-looking approach to politics (and that can either manifest itself in combative, "us versus them" populism or populism that looks to foster global cooperation on things like climate change and immigration, while still preserving a nationalistic stance on trade and the economy), monetary stimulus will be wholly insufficient after having exhausted itself after the crisis.

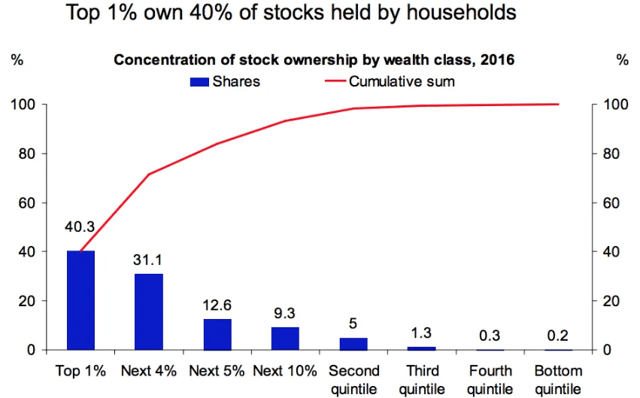

But it won't just be insufficient, it will also be politically untenable in its current form, given that one obvious side effect of QE is the perpetuation of inequality (that's not a secret - central banks have openly discussed the subject).

Irrespective of whether you're inclined to point out the obvious contradiction in today's populists being themselves wealthy (Trump is a billionaire and even Bernie Sanders is a millionaire), populism is sold to voters as a remedy for the purportedly dire plight of the everyman and everywoman. QE as it currently operates won't serve that purpose, as it merely inflates the price of financial assets which are disproportionately concentrated in the hands of the wealthy.

(Deutsche Bank; this is a few years old, but it gets the point across)

So, monetary policy will instead be rolled out in the service of supporting policies that directly benefit "the people." In other words, MMT (or some variant thereof) is inevitable, especially as traditional models linking inflation to employment break down.

"It was significant recently that the high-profile Democrat Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez lambasted Fed Chair Powell about the Fed being consistently too hawkish," SocGen's Albert Edwards wrote last week, conjuring a famous exchange from July, when AOC asked Powell about the increasingly "faint heart beat" (as he described it) of the relationship between inflation and labor market slack.

Assuming inflation remains subdued and especially if it collapses in a downturn, Edwards writes that "the Fed will take the blame for unnecessarily killing this economic cycle and a bipartisan consensus will usher in monetary madness like we have never seen before."

"Monetary madness theory" is Albert's play on "MMT."

Once this plays out, the general assumption is that the decades-old bond bull market will meet its end in dramatic fashion. If there's anything that would shake even the most ardent deflationists out of their convictions it's the actual implementation of MMT.

Fearmongers will tell you that it wouldn't be the "good" kind of inflation, but rather the Weimar type. Lacy Hunt, for instance, argued in April that everyone would be literally "miserable" under an MMT regime. Frankly, that kind of analysis isn't very useful. If you believe, as Lacy professed to, that MMT in the US would "destabilize the entire global system in very short order," then there's really no point in trying to trade it. Just buy physical gold and canned goods.

For those interested in a non-doomsday scenario, MMT informs many a steepener thesis in addition to being the basis for what, as of now anyway, are still contrarian calls for a sudden resurgence of left-for-dead inflation pressures.

Importantly, this isn't just some thought experiment for the long-run. This is potentially imminent (the market discounts things ahead of time, after all). Here, for example, is what BofA's Michael Hartnett wrote earlier this month:

2020s: Investors soon to discount new policy regime of MMT, fiscal stimulus, debt forgiveness, Green New Deal, all very positive for “value”, negative for “yield”; but decisive policy & investment shifts await.

One person who is pretty sure she knows where all of this is heading is Kelton.

"Greater coordination between fiscal and monetary authorities is almost certainly the wave of the future," she told Bloomberg in a July interview from (appropriately) Tokyo.

While Kelton said central banks won’t admit to having lost their independence, the bottom line is that "you’re going to see central banks responding in more accommodative, coordinating ways."

If you're in the deflation camp and she's even half right, you're going to be all the way wrong.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home