1965. “The Role of Employment Policy.” In Margaret S. Gordon, (ed.), Poverty in America. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company; reprinted in Minsky (2013). https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1271&context=hm_archive

参考:

Effects of Shifts of Aggregate Demand upon Income Distribution:Hyman P. Minsky (May, 1968)

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2019/05/effects-of-shifts-of-aggregate-demand.html

Modern Monetary Theory – what is new about it? – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=34200

More recently, Hyman Minsky (1965: 196) wrote:

Work should be available to all who want work at the national minimum wage. This would be a wage support law, analogous to the price supports for agricultural products. It would replace the minimum wage law; for, if work is available to all at the minimum wage, no labor will be available to private employers at a wage lower than this minimum. That is, the problem of covereage of occupations disappear. To qualify for employment at these terms, all that would be necessary would be to register at the local public employment office.

This description by Minsky clearly overlaps with the MMT construction of the Job Guarantee (Mitchell, 1998; Mosler, 1997-98), who independently conceived of a employment buffer stock being a superior way of introducing full employment and price stability in a fiat monetary system.

The use of buffer stocks to condition prices is also not exclusive to MMT. Indeed, Benjamin Graham (1937) discussed the idea of stabilising prices and standards of living by surplus storage. He documented the ways in which the government might deal with surplus production in the economy.

最近では、Hyman Minsky(1965:196)はこう書いています:

仕事は、全国最低賃金で仕事をしたいすべての人に利用可能でなければなりません。これは、農産物の価格サポートに類似した賃金サポート法になります。それは最低賃金法に取って代わります。というのは、最低賃金ですべての人が仕事に就ける場合、この最低賃金より低い賃金で民間の雇用主に労働力は与えられないからです。つまり、占領の問題は消えます。これらの条件での雇用の資格を得るために必要なのは、地元の公的雇用事務所に登録することだけです。

ミンスキーによるこの記述は、MMTのジョブ保証の構築(Mitchell、1998; Mosler、1997-98)と明らかに重複しています。 。

バッファー在庫を使用して価格を調整することも、MMTに限定されません。実際、Benjamin Graham(1937)は、余剰貯蔵による価格と生活水準の安定化のアイデアについて議論しました。彼は、政府が経済の余剰生産に対処する方法を文書化した。

機能的財政論 ミンスキーとラーナーの変化の比較検討 Part 4 レイ

無視されなければならない、と、長々と警告する一方で、法律的な障壁は考慮しなければ

ならないことも認識していた。「経済的諸勢力は、政策目的がこうした諸勢力と矛盾していたり、

たとえ原理的には達成可能であっても、プログラムに説得力がなく不必要な障害と衝突しながら

進めなければならないとしたら、プログラムをダメにしてしまうかもしれない(Minsky 2013)。

そのようなプログラムを無力化しうる経済力の1つはインフレである。彼はこう論じる。

「政策的問題とは、タイトな完全雇用を」を「物価や賃金のインフレーション的上昇なしに」

達成し、持続することである(Minsky、1972)。だがミンスキー(1965)の反貧困キャンペーンでは

「貧困ライン近傍の、あるいはそれを下回る人たちの賃金を急速に引き上げる」ことが

求められていた。彼は、この種の政策にはインフレーション的バイアスがるかもしれない、

ということを認識していた。特に低賃金労務者層の生産性(時間当たり産出高)の上昇が賃金と

ならないだろう。ミンスキー(1965,186)で示唆されているのは、高賃金産業においては

賃金上昇率は「その労務者の生産性の上昇率より低くなければならないだろう」。企業が

ただ自分たちの利潤を引き上げるだけで終わらせるのを防ぐために必要なのは、「しばしば

寡占的でもあるこうした産業のマネージャーたちが、単位費用の低下を顧客に知らせざるを

得ないようにする」確実な状態を作り出すことである(Minsky 1965, 183)。このように彼は

「効果的な利潤・物価制約はタイトな完全雇用を達成するためには必要になるだろう」

(Minsky 1972)と論じた。ミンスキーが恐れていたのは、インフレーション圧力を封じ込めることが

できなければ、「完全雇用の政治的人気」が損なわれるであろう、ということだった

(Minsky, nd 55 [※“nd”とあるが、”ib”(前出)か何かの間違い?])。

Benjamin Graham (Author) .... Storage and Stability

1937

Storage and Stability: A Modern Ever-Normal Granary (Benjamin Graham Classics) ハードカバー – 1997/12/1

Storage and Stability: The Original 1937 Edition ... - Amazon.com

New customer? ... Benjamin Graham (Author) .... Storage and Stability: A Modern Ever-Normal Granary (Benjamin Graham Classics) ... Paperback: 328 pages; Publisher: McGraw-Hill (January 22, 1998) ...

Benjamin Graham Classics - Amazon

Amazon配送商品ならStorage and Stability: A Modern Ever-Normal Granary ( Benjamin Graham Classics)が通常配送無料 ...

Irwin Marketing - Amazon

Philip R. Cateora, John Graham, Mary C Gilly作品ほか、お急ぎ便対象商品は当日お届けも可能。 ... and new learning tools including McGraw-Hill's Connect with its adaptive ... disservice to students who are forced to navigate your unwieldy tome.

Storage and Stability Benjamin Graham First Edition

New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc, 1937. First edition of the author's classic third book. Octavo, original red ...

ベンジャミン・グレアムが考える「インフレ」と「企業収益」の関係と株式投資の有効性を賢明なる投資家から読み解く | マネリテ!「株式投資初心者の勉強 虎の巻」

https://manelite.jp/graham-mindset-2/ベンジャミン・グレアムが考える「インフレ」と「企業収益」の関係と株式投資の有効性を賢明なる投資家から読み解く

前回のコンテンツの内容を踏まえ、今回は「インフレーション」と「企業収益」の相関性についてのベンジャミン・グレアム氏の考え方を紹介していきます。

インフレと企業「収益」の相関性

大前提として、ベンジャミン・グレアム氏はインフレと企業収益(利益率)の相関性は低いと結論づけています。

グレアム氏は企業収益の増加はインフレによるものではなく、稼ぎ出して「利益」の「再投資」を継続しているからであるとしています。

グレアム氏が投資に従事していた1966年〜1970年まで、インフレにより生活費は22%上昇しました。

しかし、1965年以来株価は全体的に落ち込んだ等の事例が複数発見できることを根拠としています。

投資家は、考え方、希望、不安、達成感や不満、そしてとりわけ次に何をすべきかという決定を、投資人生を回顧することからではなく、年一年と積み重ねる経験によって導き出すのだ。この点について、われわれは断言できる。インフレ(またはデフレ)状態と普通株の株価・収益変動の間には密接な関係はない。良い例は、最近の1966〜70年までのことである。この間、生活費は22%上昇し、5年ごとに見た場合、1946〜50年の期間以降で最も目覚ましいものだった。しかし株式収益や株価は1965年以来、全体的に落ち込んだ。それに先立つ5年間の記録では、生活費があまり上昇しなかったのに対し、株式収益は目覚ましく上昇するというような全く逆の現象が起きている。(引用:賢明なる投資家 - 割安株の見つけ方とバリュー投資を成功させる方法)

ROEに着目

ROEは代表的な投資指標であり、計算式は「当期純利益 ÷ 自己資本 × 100」となります。

【ROE = 当期純利益 ÷ 自己資本 × 100】

グレアム氏はROEは経済活動全般によって影響は受けます。

しかし、インフレ率(「PPI」(=生産者物価)や「CPI」(=消費者物価))と共に上昇する傾向は見せておらず、例えばインフレが企業株価に良い影響を与えているとするのであれば、それまでの資本に対する収益率が上昇すると指摘しています。

「PPI」(=生産者物価)Producer Price Indexの略称で、生産者物価指数のこと。米国の労働省が、米国内の製造業者の販売価格を約1万品目について調査し、発表するものである。製造段階別(最終財・中間財・原材料)、品目別、産業別の数値が毎月発表される。PPIはインフレ率(物価上昇率)の判断に用いられ、日本の「卸売物価指数」に近い統計である。日本の卸売物価は輸送費や流通マージンを含んだものになっているのに対して、PPIは生産者の出荷時点での価格を対象としたものになっている。「CPI」(=消費者物価)総務省(省庁再編以前:総務庁)が毎月発表する統計で、「東京都区分」と「全国」の2種類がある。すべての商品を総合した「総合指数」のほか、物価変動の大きい生鮮食品を除いた「生鮮食品除く総合指数」も発表される。商品の販売には卸売と小売の区別がある。消費者に対しての販売を小売という。スーパーや商店で買い物をするとき、小売商から小売りされているといえる。この段階での価格を指数化したものが「消費者物価指数」である。「消費者物価指数」は、家計でよく消費するもの、長期間値段を調査できるものなどいくつかの条件をもとに、500品目以上の値段を集計して算出される。タクシー代やクリーニング代といったサービスの料金も含まれる。なお、元本が全国消費者物価指数(CPI)に連動して増減し、金利は利払い時の想定元金額に応じて支払われる国債のことを物価連動国債という。

わかりやすく解説をすると、例えば100万円を企業Aに投下し、その企業Aが10万円の純利益を上げます。

その後、インフレが20%上昇ーー。わかりやすいようにシンプルな説明になりますが、企業の商品の販売価格も20%上がり、利益も10万円→20%増の12万円になるとします。

まさに、ROEは12%に上昇するはずが、歴史を辿ると上昇していない、ということをグレアム氏は指摘している、ということです。

グレアム氏が考える米国の株価上昇の要因とは?

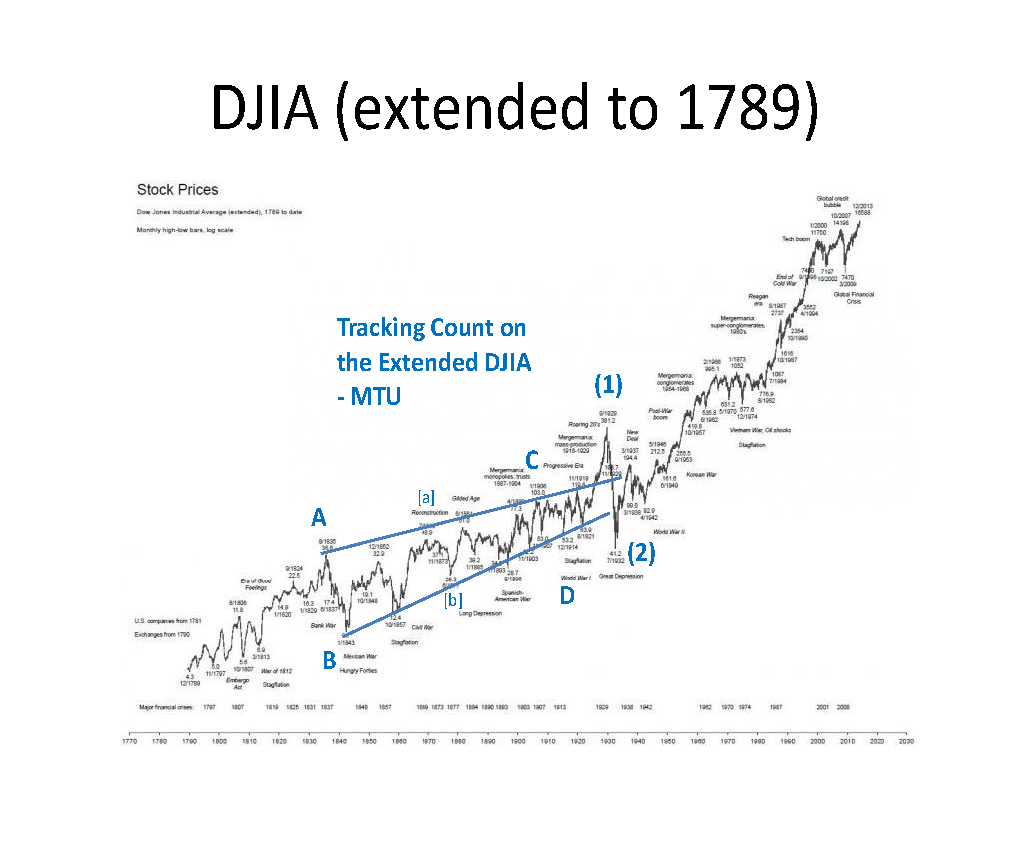

100年後のダウ工業株30種指数について、19日終値の2万2370.80ドルから「100万ドル超」になると予想。1世紀前に81ドル程度だったことを考えると、不可能ではないと述べた。バフェット氏は、フォーブス誌が1982年に最も富裕な米国人400人のリストを公表して以降、1500人程度がリストに登場したが「ショートセラー(空売りをする人)は誰もいない」と指摘。「米国をショートにすると、常に負けてきた。これからもそうだ」と強調した。

グレアム氏が企業の利益は再投資を重ねることで実現すると述べたことを冒頭で触れました。

企業Aに100万円投資、利益10万円、ROE10%ーー。

この利益10万円を再投資し次の年は11万円に、と積み重ねていくことこそが米国の株価が上昇している本当の要因であり、インフレはむしろ企業のROEを落とし、企業成長の阻害要因でもあるとしています。

その要因として、「生産性を上回る賃金の上昇」「資本追加に迫られたこと」としています。

つまり、生産性を上回る勢いで賃金が上昇し、インフレによる業態拡大による工場設備増築など、本来の企業成長を超えるスピードで物事が進んでしまい、結果的に減益に落ち込んでしまう、ということを意味しているのです。

個人投資家のインフレに対する防衛策は?

「金」「不動産」がインフレ時の投資先として代表的ですが、グレアム氏は否定しています。

「不動産」はその価値を測るのは非常に難しい。

「金」は長年にわたりインフレ率より低い価格上昇率しか記録しておらず(1935-1972年で35%の上昇に止まる)、インカムゲインとなる配当金がありません。

株式と違い、特に金に関しては、何も配当金を産みだしていないこと理由として挙げています。

まとめ

ベンジャミン・グレアム氏のインフレと企業収益、ROEの関係性、及び、インフレ時の投資対策の考え方について紹介してきました。

先人の教えは、株式投資の実践で役立つものばかりですので、知識をどんどん吸収していくようにしましょう。

以上、ベンジャミン・グレアムが考える「インフレ」と「企業収益」の関係と株式投資の有効性を賢明なる投資家から読み解く…の話題でした!

[おすすめネット証券ランキング]

2019年現在で株式投資を始めるにあたり、マネリテ編集部が厳選したネット証券をランキング形式にまとめておりますので参考にしてみてください。

Job Guarantee and Inflation Control

In this vein we are suggesting that politicians should set a minimum acceptable living standard and ensure that a base level job is always available to allow all citizens to achieve that living standard independent of welfare payments. This is the essence of the JG. Analogous to the central bank’s function of lender of the last resort, the JG functions as a buffer which absorbs all potential employment, at the accepted minimum wage. Government then is also the employer of the last resort.

In this vein we are suggesting that politicians should set a minimum acceptable living standard and ensure that a base level job is always available to allow all citizens to achieve that living standard independent of welfare payments. This is the essence of the JG. Analogous to the central bank’s function of lender of the last resort, the JG functions as a buffer which absorbs all potential employment, at the accepted minimum wage. Government then is also the employer of the last resort.

An additional advantage is that by creating an employment buffer stock government also facilitates inflation control.

Please read my blog – Full Employment with a Job Guarantee – for a detailed introduction to the JG concept.

While it is easy to characterise the JG as purely a public sector job creation strategy, it is important to appreciate that it is actually a macroeconomic policy framework designed to deliver full employment and price stability based on the principle of buffer stocks where job creation and destruction is but one component.

The idea came to me in 1978 when I was studying agricultural economics at the University of Melbourne. My earlier works discusses the link between the JG approach and the agricultural price support buffer stock schemes like the Wool Floor Price Scheme introduced by the Australian Government in 1970.

This was a system where the government desired to stabilised farm incomes and so agreed on a price for wool with the farmers. The government would then purchase excess wool supplied into the market to ensure the agreed price was maintained and in better times sell wool. They kept the wool in big stores spread all around the country.

So the government held buffer stocks of wool to manage the price. The JG is a buffer stock scheme too.

While generating full employment for wool production, there was an issue of what constituted a reasonable level of output in a time of declining demand.

The argument is not relevant when applied to unemployed labour. If there is a price guarantee below the prevailing market price and a buffer stock of working hours constructed to absorb the excess supply at the current market price, then a form of full employment can be generated without tinkering with the price structure.

The other problem with commodity buffer stock systems is that they encouraged over-production, which ultimately made matters worse when the scheme were discontinued and the product was dumped onto the market. These objections to do not apply to maintaining a labour buffer stock as no one is concerned that employed workers would have more children than unemployed workers.

Benjamin Graham wrote in the 1930s about the idea of stabilising prices and standards of living by surplus storage. He documents how a government might deal with surplus production in the economy. He said the:

State may deal with actual or threatened surplus in one of four ways: (a) by preventing it; (b) by destroying it; (c) by “dumping” it; or (d) by conserving it.

In the context of an excess supply of labour, governments now choose the dumping strategy via the NAIRU. It makes much better sense to use the conservation approach via a JG. Graham (1937: 34) noted:

The first conclusion is that wherever surplus has been conserved primarily for future use the plan has been sensible and successful, unless marred by glaring errors of administration. The second conclusion is that when the surplus has been acquired and held primarily for future sale the plan has been vulnerable to adverse developments …

The distinction is important in the JG model. The Australian Wool Scheme was an example of storage for future sale and was not motivated to help the consumer of wool but the producer.

The JG policy is an example of storage for use where the “reserve is established to meet a future need which experience has taught us is likely to develop” (Graham, 1937: 35).

Graham also proposed a solution to the problem of interfering with the relative price structure when the government built up the surplus. In the context of the JG policy, this means setting a JG wage below the private market wage structure. To avoid disturbing the private sector wage structure and to ensure the JG is consistent with price stability, the JG wage rate should probably be set at the current legal minimum wage, though an initially higher JG wage may be offered if the government sought to combine the JG policy with an industry policy designed to raise productivity.

Under the JG, the public sector offers a fixed wage job, which we consider to be price rule spending, to anyone willing and able to work, thereby establishing and maintaining a buffer stock of employed workers. This buffer stock expands (declines) when private sector activity declines (expands), much like today’s unemployed buffer stocks, but potentially with considerably more liquidity if properly maintained.

The JG thus fulfills an absorption function to minimise the real costs currently associated with the flux of the private sector. When private sector employment declines, public sector employment will automatically react and increase its payrolls.

The nation always remains fully employed, with only the mix between private and public sector employment fluctuating as it responds to the spending decisions of the private sector. Since the JG wage is open to everyone, it will functionally become the national minimum wage.

Inflation control under a Job Guarantee

The fixed JG wage provides an in-built inflation control mechanism. In an earlier published paper I called the ratio of JG employment to total employment the Buffer Employment Ratio (BER).

The BER conditions the overall rate of wage demands. When the BER is high, real wage demands will be correspondingly lower. If inflation exceeds the government’s announced target, tighter fiscal and monetary policy would be triggered to increase the BER, which entails workers transferring from the inflating sector to the fixed price JG sector.

Ultimately this attenuates the inflation spiral. So instead of a buffer stock of unemployed being used to discipline the distributional struggle, the JG policy achieves this via compositional shifts in employment. That is it can also deal with a supply-shock that generates distributional demands that ultimately cause inflation.

The BER that results in stable inflation is called the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Buffer Employment Ratio (NAIBER). It is a full employment steady state JG level, which is dependent on a range of factors including the path of the economy.

A plausible story to show the dynamics of a JG economy compared to a NAIRU economy would begin with an economy with two labour sub-markets: A (primary) and B (secondary) which broadly correspond to the dual labour market depictions. Prices are set according to mark-ups on unit costs in each sector.

Wage setting in A is contractual and responds in an inverse and lagged fashion to relative wage growth (A/B) and to the wait unemployment level (displaced Sector A workers who think they will be re-employed soon in Sector A).

A government stimulus to this economy increases output and employment in both sectors immediately. Wages are relatively flexible upwards in Sector B and respond immediately.

The compression of the A/B relativity stimulates wage growth in Sector A after a time. Wait unemployment falls due to the rising employment in A but also rises due to the increased probability of getting a job in A. The net effect is unclear.

The total unemployment rate falls after participation effects are absorbed. The wage growth in both sectors may force firms to increase prices, although this will be attenuated somewhat by rising productivity as utilisation increases. A combination of wage-wage and wage-price mechanisms in a soft product market can then drive inflation. This is a Phillips curve world.

To stop inflation, the government has to repress demand. The higher unemployment brings the real income expectations of workers and firms into line with the available real income and the inflation stabilises – a typical NAIRU story.

Introducing the JG policy into the depressed economy puts pressure on Sector B employers to restructure their jobs in order to maintain a workforce. For given productivity levels, the JG wage constitutes a floor in the economy’s cost structure. The dynamics of this economy change significantly.

The elimination of all but wait unemployment in Sector A and frictional unemployment does not distort the relative wage structure so that the wage-wage pressures that were prominent previously are now reduced.

The wages of JG workers (and hence their spending) represents a modest increment to nominal demand given that the state is typically supporting them on unemployment benefits. It is possible that the rising aggregate demand softens the product market, and demand for labour rises in Sector A.

But there are no new problems faced by employers who wish to hire labour to meet the higher sales levels in this environment. They must pay the going rate, which is still preferable, to appropriately skilled workers, than the JG wage level. The rising demand per se does not invoke inflationary pressures if firms increase capacity utilisation to meet the higher sales volumes.

With respect to the behaviour of workers in Sector A, one might think that the provision of the JG will lead to workers quitting bad private employers. It is clear that with a JG, wage bargaining is freed from the general threat of unemployment.

However, it is unclear whether this will lead to higher wage demands than otherwise. In professional occupational markets, some wait unemployment will remain. Skilled workers who are laid off are likely to receive payouts that forestall their need to get immediate work.

They have a disincentive to immediately take a JG job, which is a low-wage and possibly stigmatised option. Wait unemployment disciplines wage demands in Sector A. However, demand pressures may eventually exhaust this stock, and wage-price pressures may develop.

A crucial point is that the JG does not rely on the government spending at market prices and then exploiting multipliers to achieve full employment which characterises traditional Keynesian pump-priming. Traditional Keynesian remedies fail to provide an integrated full employment-price anchor policy framework. In fact, a Keynesian policy agenda would impact more significantly on inflation if it was true that a JG was inflationary as a result of its impacts on demand in the product market.

Would the NAIBER will be higher than the NAIRU?

This last point invokes a fierce debate as to relative sizes of the NAIBER vis-à-vis the NAIRU. Some commentators argue that the NAIBER would have to be greater than the NAIRU for an equivalent amount of inflation control.

There are two strands to this argument. First, the intuitive but somewhat inexact view is that because JG workers will have higher incomes (than when they were unemployed) a switch to this policy would always see demand levels higher than under a NAIRU world.

As a matter of logic then, if the NAIRU achieved output levels commensurate with price stability then, other things equal, a higher demand level would have to generate inflationary impulses. So according to this view, the level of unemployment associated with the NAIRU is intrinsically tied to a unique level of demand at which inflation stabilises.

Second, and related, it is claimed that the introduction of the JG reduces the threat of unemployment which serves to discipline the wage setting process. The main principle of a buffer stock scheme like the JG is straightforward – it buys off the bottom (at zero bid) and cannot put pressure on prices that are above this floor. The choice of the floor may have once-off effects only.

It should be noted that while it is clear that JG workers will enjoy higher purchasing power under a JG compared to their outcomes under a NAIRU policy, it is not inevitable that aggregate demand overall would rise with the introduction of JG.

But assuming aggregate demand is higher when the JG is introduced than that which prevailed in the NAIRU economy, a traditional economist (and some Post Keynesians) might wonder why inflation is not inevitable as we replace unemployment with (higher paying) employment.

Rising demand per se does not necessarily invoke inflationary pressures because by definition, the extra liquidity is satisfying a net savings desire by the private sector.

Additionally, in today’s demand constrained economies, firms are likely to increase capacity utilisation to meet the higher sales volumes. Given that the demand impulse is less than required in the NAIRU economy, it is clear that if there were any demand-pull inflation it would be lower under the JG. So there are no new problems faced by employers who wish to hire labour to meet the higher sales levels.

Any initial rise in demand will stimulate private sector employment growth while reducing JG employment and spending.

The impact on the price level of the introduction of the JG will also depend on qualitative aspects of the JG pool relative to the NAIRU unemployment buffer. It is here that the so-called threat debate enters.

The JG buffer stock is a qualitatively superior inflation fighting pool than the unemployed stock under a NAIRU. Therefore the NAIBER will be lower than the NAIRU which means that employment can be higher before the inflation barrier is reached.

In the NAIRU logic workers may consider the JG to be a better option than unemployment. Without the threat of unemployment, wage bargaining workers then may have less incentive to moderate their wage demands notwithstanding the likely disciplining role of wait unemployment in skilled labour markets.

However, when wait unemployment is exhausted private firms would still be required to train new workers in job-specific skills in the same way they would in a non-JG economy.

Further, JG workers are far more likely to have retained higher levels of skill than those who are forced to succumb to lengthy spells of unemployment. It is thus reasonable to assume that an employer would consider a JG worker, who is already demonstrating commitment to working, a superior training prospect relative to an unemployed and/or hidden unemployed worker. This changes the bargaining environment rather significantly because the firms now have reduced hiring costs. Previously, the same firms would have lowered their hiring standards and provided on-the-job training and vestibule training in tight labour markets.

The functioning and effectiveness of the buffer employment stock is critical to its function as a price anchor. Condition and liquidity is the key. Just as soggy rotting wool is useless in a wool price stabilisation scheme, labour resources should be nurtured as human capital constitutes the essential investment in future growth and prosperity.

There is overwhelming evidence that long-term unemployment generates costs far in excess of the lost output that is sacrificed every day the economy is away from full employment. It is clear that the more employable are the unemployed the better the price anchor will function.

The JG policy thus would reduce the hysteretic inertia embodied in the long-term unemployed and allow for a smoother private sector expansion. Therefore JG workers would constitute a credible threat to the current private sector employees. When wage pressures mount, an employer would be more likely to exercise resistance if she could hire from the fixed-price JG pool.

As a consequence, longer term planning with cost control would be enhanced. So in this sense, the inflation restraint exerted via the NAIBER is likely to be more effective than using a NAIRU strategy.

Another associated factor relates to the behaviour of professional occupational markets. In those markets, while any wait unemployment will discipline wage demands, the demand pressures may eventually exhaust this stock and wage-price pressures may develop.

With a strong and responsive tertiary education sector combined with strong firm training processes skill bottlenecks can be avoided more readily under the JG than with an unemployed buffer stock in place. The JG workers would be already maintaining their general skills as a consequence of an on-going attachment to the employed workforce.

The qualitative aspects of the unemployed pool deteriorate with duration making the transition back in the labour force more problematic. As a consequence, the long-term unemployed exert very little downward pressure on wages growth because they are not a credible substitute.

Responsible fiscal practice in MMT

This is the macroeconomic sequence that defines responsible fiscal policy practice in MMT. This is basic macroeconomics and the debt-deficit-hyperinflation neo-liberals seem unable to grasp it:

1. The sovereign government, which is not revenue-constrained because it issues the currency, has a responsibility for seeing that the workforce is fully employed.

2. Full employment means less than 2 per cent unemployment, zero underemployment and zero hidden unemployment.

3. The sovereign government can purchase any real good or service that is available for sale in the market at any time. It never has to finance this spending unlike a household which uses the currency issued by the sovereign government. The household always has to finance its spending (as do state and local governments in a federal system).

4. The non-government sector typically decides (in aggregate) to save a proportion of the income that is flowing to it. This desire to save motivates spending decisions which result in the flow of spending being less than the income produced. If nothing else happened then firms would reduce output and income would fall (as would employment) and households would find they were unable to achieve their desired saving ratio.

5. The government sector must in this situation fill the spending gap left by the non-government sector’s decision to withdraw some spending (in relation to its income). If the government does increase its net contribution to spending (that is, run a budget deficit) up to the point that total spending now equals total income then firms will realise their planned output sales and retain current employment levels.

6. The government sector’s net position (spending minus revenue) is the mirror image of the non-government’s net position. So a government surplus is equal $-for-$, cent-for-cent to a non-government deficit and vice versa. So if the non-government sector is in surplus (a net saving position) then income adjustments will render the government sector in deficit whether it plans to be in that state or not. If income is falling in the face of rising saving behaviour of the non-government sector and that spending gap is not filled by government net spending then the budget deficit will rise (as income adjustments cause tax revenue to fall and welfare payments to rise). You end up with a deficit but the economy is at a much less satisfactory position than would have been the case if the government had have “financed” the non-government saving desire in the first place and kept employment levels high.

7. A fiscally-responsible government will attempt to maintain spending levels sufficient to fill any saving but not push nominal aggregate spending beyond the full capacity level of output.

Conclusion

Given the overwhelming central bank focus on price stability, and the critical roll of today’s unemployed buffer stocks of unemployed, we argue that functioning and effectiveness of the buffer stock is critical to its function as a price anchor.

Condition and liquidity are the keys. Just as soggy rotting wool is useless in a wool price stabilisation scheme, labour resources should be nurtured as human capital constitutes the essential investment in future growth and prosperity. There is overwhelming evidence that long-term unemployment generates costs far in excess of the lost output that is sacrificed every day the economy is away from full employment.

It is clear that the more employable are the unemployed the better the price anchor will function. The government has the power to ensure a high quality price anchor is in place and that continuous involvement in paid-work provides returns in the form of improved physical and mental health, more stable labour market behaviour, reduced burdens on the criminal justice system, more coherent family histories and useful output, if well managed.

It is also the case the training in a paid-work environment is more effective than contextually isolated training schemes, which have become the fashion under the active labour market programs pursued by governments in all countries over the last two decades.

Now don’t say MMT doesn’t integrate a concern for inflation at the level of first principles.

Modern Monetary Theory – what is new about it? – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=34200Modern Monetary Theory – what is new about it?

In a few weeks I am off to the US to present a keynote talk at the – International Post Keynesian Conference – which will be held at the University of Missouri – Kansas City between September 15-18, 2016. I will also be giving some additional talks in Kansas City during that week if you are around and interested. The keynote presentation is scheduled for Friday, September 16 at 17:00. The topic of my keynote presentation will ‘What is new about MMT?’ and will challenge several critics from both the neo-liberal mainstream and from within the Post Keynesian family that, indeed, there is nothing new about MMT – they knew it all along! Well the truth of it is that these characters clearly didn’t previously know or understand a lot of key insights that MMT now offers. No matter how hard they try to reinvent what they knew, the facts are obvious. MMT makes some novel contributions to our knowledge base and shows why a lot of so-called mainstream macroeconomic theory that parades as ‘knowledge’ is, in fact, non-knowledge. This blog and the second-part will provide some notes on the paper I am writing (with my colleague Martin Watts) on this topic.

1. Introduction

Over the last several years, after an even longer period of being ignored, the ideas attributed to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have entered the popular discourse.

While many commentators are viewing the core ideas as a progressive answer to fill the void created by a mainstream macroeconomics that has lost credibility, an increasing number of economists have attempted to discredit MMT.

Interestingly, the economists seeking to discredit MMT have not been confined to those working within the mainstream tradition (New Keynesian or otherwise). Indeed, considerable hostility has emerged from those who identify as working within the so-called Post Keynesian tradition, even if that cohort is difficult to define clearly.

Earlier criticisms by so-called Post Keynesian economists, specifically targetted at their disdain for the Job Guarantee policy advocated by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents (see Aspromourgos 2000, Kadmos and O’Hara 2000, King 2001, Kriesler and Halevi 2001, Mehrling 2000 and Sawyer, 2003). These specific issues were dealt with in Mitchell and Wray (2005).

The more recent criticisms have become more general in scope and can be split into two different strands. It is these more recent criticisms that we address in this paper, given that we identify that they are directed at the overall credibility of the MMT approach, as an alternative to the mainstream macroeconomic approach.

At the outset, we consider mainstream macroeconomics to be the type of economics that is almost universally taught in undergraduate courses in universities around the world and represents the usual dialogue in the financial press.

The first line of attack comes from those who claim ‘we knew it all along’ – that MMT offers nothing new (for example, Palley, 2013, 2014; Wren-Lewis, 2016a).

Since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, which exposed the inadequacies of mainstream macroeconomic theory and practice, many economists operating in the mainstream tradition have attempted to distance themselves from this failure.

This attempt at re-establising credibility is a common tactic for a degenerative paradigm in science. Economists operating in the New Keynesian tradition, for example, which in their standard models did not even have a financial sector, now claim that the crisis – cause and solution – was entirely comprehensible within a ‘modified’ New Keynesian approach.

Krugman (2009) attempted to deal with this by accusing the so-called “freshwater economists” who think that Keynesian economics were “fairy tales that have been proved to be false” of failure and suggesting that the “saltwater economists” (which he identifies with) were pragmatists who considered “that Keynesian economics remains the best framework we have for making sense of recessions and depressions”.

Tied up in this attempt to resurrect the credibility of elements of mainstream theory were the strident criticisms from MMT proponents, who had unambiguously foreshadowed the likely implications of the private debt buildup as early as the 1990s while the mainstream economists were declaring that “central problem of depression-prevention has been solved” (Lucas, 2003: 1), effectively asserting that the business cycle was dead and waxing lyrical about the ‘Great Moderation’ (Bernanke, 2004).

These criticisms and growing interest in MMT ideas among academics and the broader community also challenged Post Keynesian economists, who also had not fully appreciated the dangerous financial trends in the 1990s and were increasingly being diverted into post modernist ventures focusing on gender, race, metholodology etc.

Initially, MMT was considered to be too marginal to pose any threat.

But in the last five years or so, it has attracted more attention from both mainstream and Post Keynesian economists, as more people become attracted to the capacity of MMT ideas to embrace the reality of the situation – a major weakness of existing mainstream, and, it has to be said, Post Keynesian economics.

In a this vein, the New Keynesian economist Simon Wren-Lewis (2016) attacked MMT on two grounds. He wrote:

1. MMT seems obsessed with the accounting detail of government transactions2. This seemed to lead to ideas that I thought were standard bits of macroeconomics

In a similar vein, the self-described Post Keynesian economist, Thomas Palley (2013: 2) wrote that:

… the macroeconomics of MMT is a restatement of elementary well-understood Keynesian macroeconomics. There is nothing new in MMT’s construction of monetary macroeconomics that warrants the distinct nomenclature of MMT.

Palley gets more strident in his claim (2013: 7) that “There is nothing new about its theory, and the theory it uses is simplistic and inadequate for the task. Furthermore, MMT-ers have failed to provide a formal model that explicates their claims.”

Palley concluded that (2013: 14):

In fact, MMT is an inferior rendition of the analysis of money-financed fiscal policy contained in the stock-flow consistent ISLM analysis of Blinder and Solow (1973) and Tobin and Buiter (1976).

We should immediately be suscipicious of such claims given that MMT proponents would not consider ISLM analysis to be remotely cognate to their understanding of the way the monetary system functions.

The ‘nothing new’ criticism is sometimes accompanied by the put-down that “MMTers also seem curiously averse to equations” (Wren-Lewis, 2016a). Palley’s reference to a “formal model” repeats the claim that an economic proposition that is not backed up by some mathematical expressions is clearly deficient.

We do not deal with that criticism here. Suffice to say that the great works of Marx and Keynes, among others would be disregarded if the inclusion of mathematical squiggles was the demarcation criteria between deficient and sound analysis. But it is also not correct that MMT economists have avoided formal expressions when they consider them to be useful in advancing comprehension (see Mitchell and Muysken, 2008).

The second line of attack has come from Post Keynesian economists, who have claimed MMT presents a fictional account of the world that we live in and in that sense fails to advance our understanding of how the modern monetary system operates (Lavoie, 2011; Fiebiger 2012a, 2012b).

A corollary of the ‘fictional world of MMT’ attack is that “MMT policy recommendations take little account of political economy difficulties” (Palley, 2013: 2) – in other words, there is a dysfunctional naivety in MMT.

Their main concerns appear to be focused on the way MMT ‘consolidates’ the central bank and treasury functions into the ‘government sector’ and juxtaposes this with the non-government sector.

Specific claims focus on balance sheet analysis and the varying implications of the treasury selling debt to the central bank or to the non-government sector bond dealers.

Fiebiger (2012a), for example, takes exception to the statements made by MMT author Randy Wray (1998: 78) along the lines that the “Treasury spends before and without regard to either previous receipt of taxes or prior bond sales”. In his view these class of statements are wrong because they ignore the institutional reality that governs the separation of the central bank and the treasury and financially constrains the latter.

Accordingly, he asserts that this ignorance of the contraints on the treasury “defines MMT and is defective” (Fiebiger, 2012: 2).

Marc Lavoie (2014) seems to think this criticism is important enough to devote a whole section in his book to repeating it.

The problem is that these critics have failed to understand the intent of the MMT consolidation of the central bank and treasury functions into a whole government sector.

Long before Fiebiger or Lavoie had entered the debate, Mitchell (2009) has observed that governments had erected elaborate voluntary contraints on their operational freedom to obscure the intrinsic capacities that the monopoly issuer of the fiat currency possessed.

In the same way that Marx considered the exchange relations to be an ideological veil obscuring the intrinsic value relations in capitalist production and the creation of surplus value, MMT identifies two levels of reality.

The first level defines the intrinsic characteristics of the the monopoly fiat currency issuer which clearly lead us to understand that such a government can never run out of the currency it issues and has to first spend that currency into existence before it can ever raise taxes or sell bonds to the users of the currency – the non-government sector.

There should be no question about that.

Once that level of understanding is achieved then MMT recognises the second level of reality – the voluntary institutional framework that governments have put in place to regulate their own behaviour.

These accounting frameworks and fiscal rules are designed to give the (false) impression that the government is financially constrained like a household – that is, in context, has to either raise taxes to spend or issue debt to spend more than it raises in taxes.

Fiebiger claims MMT ignores these constraints. But Mitchell (2009) wrote extensively about their existence and their functions within the neo-liberal approach to government policy.

Importantly, by introducing the consolidated government sector, MMT strips way the veil of neo-liberal ideology that mainstream macroeconomists use to restrict government spending.

We learn that these contraints are purely voluntary and have no intrinsic status. This allows us to understand that governments lie when they claim they have run out of money and therefore are justified in cutting programs that advance the well-being of the general population.

By exposing the voluntary nature of these constraints, MMT pushes these austerity-type statements back into the ideological and political level and rejects them as financial verities.

The Post Keynesian critics appear to be oblivious to this veil of ideology and the purpose it serves.

New Keynesians also attack MMT in this vein.

It is clear that several of these commentators have chosen this ‘shoot-from-the-hip’ approach, and in doing so, have grossly misrepresented what can be found in the primary academic MMT literature (published by the original academic developers of that literature).

Paul Krugman (2011) reasserting the central conclusions that the mainstream IS-LM macroeconomic framework, wrote:

I’m not clear on whether they … [MMT proponents] … realize that a deficit financed by money issue is more inflationary than a deficit financed by bond issue.

Krugman seems to misunderstand the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issues debt. A fiscal deficit not matched by debt issuance to the non-

…

2. MMT and the Phillips Curve

One of the central macroeconomic areas where MMT has clearly made an original contribution has been in terms of inflation theory, and, more specifically, the discussion of a the trade-off between inflation and unemployment (that is, the Phillips curve debate).

First, public sector job creation has a long tradition in policy thinking even if it is now largely discredited by the mainstream economists, who, if they advocate any demand-side measures at all, prefer to promote ineffective solutions such as private wage subsidies.

Clearly, there is no claim that MMT invented the concept of public sector job creation as a solution to unemployment or as a path to full employment, even though the use of employment guarantees is a centrepiece of MMT’s macroeconomic policy approach.

Importantly, public sector job creation is seen by MMT as a macroeconomic rather than a microeconomic strategy – part of an overall macroeconomic stability approach. We will come back to that presently.

Second, the idea of using employment guarantees is also not exclusive to MMT and in fact has a long history. The debates surrounding the ‘right to work’ and the responsibilities of the state in ensuring everyone who wants to work has an opportunity go back hundreds of years.

More recently, Hyman Minsky (1965: 196) wrote:

Work should be available to all who want work at the national minimum wage. This would be a wage support law, analogous to the price supports for agricultural products. It would replace the minimum wage law; for, if work is available to all at the minimum wage, no labor will be available to private employers at a wage lower than this minimum. That is, the problem of covereage of occupations disappear. To qualify for employment at these terms, all that would be necessary would be to register at the local public employment office.

This description by Minsky clearly overlaps with the MMT construction of the Job Guarantee (Mitchell, 1998; Mosler, 1997-98), who independently conceived of a employment buffer stock being a superior way of introducing full employment and price stability in a fiat monetary system.

The use of buffer stocks to condition prices is also not exclusive to MMT. Indeed, Benjamin Graham (1937) discussed the idea of stabilising prices and standards of living by surplus storage. He documented the ways in which the government might deal with surplus production in the economy.

最近では、Hyman Minsky(1965:196)はこう書いています:

仕事は、全国最低賃金で仕事をしたいすべての人に利用可能でなければなりません。これは、農産物の価格サポートに類似した賃金サポート法になります。それは最低賃金法に取って代わります。というのは、最低賃金ですべての人が仕事に就ける場合、この最低賃金より低い賃金で民間の雇用主に労働力は与えられないからです。つまり、占領の問題は消えます。これらの条件での雇用の資格を得るために必要なのは、地元の公的雇用事務所に登録することだけです。

ミンスキーによるこの記述は、MMTのジョブ保証の構築(Mitchell、1998; Mosler、1997-98)と明らかに重複しています。 。

バッファー在庫を使用して価格を調整することも、MMTに限定されません。実際、Benjamin Graham(1937)は、余剰貯蔵による価格と生活水準の安定化のアイデアについて議論しました。彼は、政府が経済の余剰生産に対処する方法を文書化した。

Graham (1937: 18) said:

The State may deal with actual or threatened surplus in one of four ways: (a) by preventing it; (b) by destroying it; (c) by ‘dumping’ it; or (d) by conserving it.

In the context of an excess supply of labour, governments in the neo-liberal era adopted the “dumping” strategy via the so-called Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) approach, which used buffer stocks of unemployed to condition the inflationary process.

It made much better sense to use the conservation approach.

Graham (1937: 34) notes that

The first conclusion is that wherever surplus has been conserved primarily for future use the plan has been sensible and successful, unless marred by glaring errors of administration. The second conclusion is that when the surplus has been acquired and held primarily for future sale the plan has been vulnerable to adverse developments …

In the above quote from Minsky (1965) you also see a reference to agricultural price support schemes akin to the work of Benjamin Graham.

Graham’s distinction was important in the MMT development of the Job Guarantee. Mitchell (1998b) writes that the motivation for his work on the buffer stock employment model began when he was a fourth-year economics student at the University of Melbourne in 1978.

グラハム(1937:18)は言った:

国家は、次の4つの方法のいずれかで実際のまたは脅迫された余剰に対処することができます。

(a)それを防ぐことにより;

(b)破壊すること。

(c)それを「ダンプ」する。または

(d)保存することにより。

労働者の過剰供給という文脈において、新自由主義時代の政府は、いわゆる非加速インフレ失業率(NAIRU)アプローチによる「ダンピング」戦略を採用しました。処理する。

保存アプローチを使用するほうがはるかに理にかなっています。

グラハム(1937:34)は、

最初の結論は、将来の使用のために主に余剰が保存されている場所はどこでも、管理の明白なエラーによって損なわれない限り、計画は賢明で成功したということです。第二の結論は、主に将来の販売のために余剰金を取得して保有した場合、計画は不利な展開に対して脆弱であるということです…

上記のミンスキーの引用(1965)には、ベンジャミン・グラハムの仕事に似た農業価格支援制度への言及もあります。

グラハムの区別は、ジョブ保証のMMT開発において重要でした。 Mitchell(1998b)は、バッファストック雇用モデルに関する研究の動機は、1978年にメルボルン大学で経済学4年生だったときに始まったと書いています。

ジョブ保証のアイデアの基礎は、1970年11月にオーストラリア連邦政府によって導入されたウール最低価格制度に参加した一連の講義の中で生まれました。

The basis of the Job Guarantee idea came during a series of lectures he attended on the Wool Floor Price Scheme introduced by the Commonwealth Government of Australia in November 1970.

The scheme was relatively simple and worked by the Government establishing a floor price for wool after hearing submissions from the Wool Council of Australia and the Australian Wool Corporation (AWC). The Government then guaranteed that the price would not fall below that level by the AWC purchasing stocks of wool in the auction markets if there were excess supplies and storing the wool in large stores. When the wool clip was deficient in any year, the AWC would sell stock from the store to stabilise the price.

In effect, the Wool Floor Price Scheme generated ‘full employment’ for wool production. Clearly, there was an issue in the wool situation of what constituted a reasonable level of output in a time of declining demand. The argument is not relevant when applied to available labour.

Application of the principle to labour is clear. If there was a price guarantee below the ‘prevailing market price’ and a buffer stock of working hours constructed to absorb the excess supply at the current market price, then the Government could generate full employment without encountering the problems of price tinkering.

At the time (and before the ‘mad cow’ disease), Mitchell (1998a, 1998b) called this approach the Buffer Stock Employment (BSE) model. Around the same time and independently, Mosler (1997-98) had outlined what he termed an Employer of Last Resort (ELR) approach, which replicated the characteristics of the BSE model.

In the context of Benjamin Graham’s work, the Wool Floor Price Scheme was an example of storage for future sale and was not motivated to help the consumer of wool but the producer. The BSE policy is an example of storage for use where the “reserve is established to meet a future need which experience has taught us is likely to develop” (Graham, 1937: 35).

Graham also analysed and proposed a solution to the problem of interfering with the relative price structure when the government built up the surplus. In the context of the BSE policy, this meant setting a buffer stock wage below the private market wage structure, unless strategic policy in addition to the meagre elimination of the surplus was being pursued.

For example, the government may wish to combine the BSE policy with an industry policy designed to raise productivity. In that sense, it may buy surplus labour at a wage above the current private market minimum.

Graham (1937: 42) considered that the surplus should “not be pressed for sale until an effective demand develops for it.” In the context of the BSE policy, this translated into the provision of a government job for all labour, which was surplus to private demand until such time as private demand increases.

On the financing issue, Graham was particularly insightful.

Once again the distinction between conservation for future use (the BSE) and conservation for future sale (Wool Floor Price Scheme) is important. Graham (1937: 43) said that the latter

… suffered from the fundamental weakness that they depended for their success upon advancing market prices … A price-maintenance venture is inherently unsound must in all probability … result in serious financial loss … But a rational plan for conserving surplus … should not involve the State in financial difficulties. The state can always afford to finance what its citizens can soundly produce. (emphasis in original)

It is clear that a fiat currency-issuing government always has the financial capacity to purchase the idle labour for sale in that currency. In other words, to eliminate cyclical unemployment through job creation.

The various proponents of MMT agreed to use the Job Guarantee terminology to aid clarity in exposition (thus embracing the various terms that had emerged in the increasingly consolidated literature (for example, BSE, ELR, Public Service Employment).

So what is so special about the Job Guarantee? Isn’t it just another public sector job creation scheme?

The stimulus to the development of the Job Guarantee as a response to mass unemployment reflects, among MMT authors are growing dissatisfaction with the extant Post Keynesian solutions to unemployment.

While those solutions clearly advocate public sector job creation supported by infrastructure investment spending stimulus they have historically relied heavily on income policy guidelines to suppress supply-side (cost) inflation. In other words, they bought into the Phillips curve trade-off argument.

These ‘generalised’ expansions clearly had difficulties with spatial targetting and enforcing an inflation anchor, not to mention the problems that income policies had historically encountered (design, enforcement, etc) (see Mitchell and Juniper, 2006).

The use of employment buffer stocks seemed to be the way to bypass the Phillips curve issue altogether while still maintaining high levels of employment.

The presence of a Phillips curve (stable or otherwise) then becomes an artifact of the way in which governments conduct their fiscal and monetary policy.

This work was clearly an advance (new) in terms of existing Post Keynesian and mainstream macroeconomics.

Conclusion

In Part 2, I will complete this section of the discussion

References:

Aspromourgos, T. (2000) ‘Is an Employer-of-Last-Resort Policy Sustainable? A Review Article’, Review of Political Economy 12(2), 141-155.

Bernanke, B. (2004) ‘The Great Moderation’, Speech at the Meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, D.C., February 20, 2004.

Blanchard, O. (2008) ‘The State of Macro’, Annual Review of Economics, 1(1), 209-228.

Fiebiger, B. (2012a) ‘Modern money and the real world of accounting of 1 -1 < 0: The U.S. Treasury does not spend as per a bank' in Working Paper No. 279, Modern Monetary Theory: A Debate, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Fiebiger, B. (2012b) ‘A rejoinder to ‘Modern money theory: a response to critics.’’ in Working Paper No. 279, Modern Monetary Theory: A Debate, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Graham, B. (1937) Storage and Stability, McGraw Hill, New York.

Kadmos, G., and P. O’Hara (2000) ‘The Taxes-Drive-Money and Employer of Last Resort Approach to Government Policy’, Journal of Economic and Social Policy, 5(1), 1-23.

King, J.E. (2001) ‘The Last Resort? Some Critical Reflections on ELR’, Journal of Economic and Social Policy 5(2), 72-76.

Krugman, P. (2009) ‘How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?’, New York Times Magazine, September 2, 2009 – http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html

Krugman, P. (2011) MMT, Again, New York Times, August 15, 2011, http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/15/mmt-again/

Lavoie, M. (2011) ‘The monetary and fiscal nexus of neo-chartalism: A friendly critique’, Journal of Economic Issues, 47(1), 1–31.

Lavoie, M. (2014) Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations, Aldershot, Edward Elgar.

Lucas, R.E. Jnr (2003) ‘Macroeconomic Priorities’, American Economic Review, 93(1), March, 1-14.

Mehrling, P. (2000) ‘Modern Money: Fiat or Credit’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 22(3), 397-406.

Mitchell, W.F. (1987) ‘The NAIRU, Structural Imbalance and the Macroequilibrium Unemployment Rate’, Australian Economic Papers, 26(48), 101-118.

Mitchell, W. F. (1996) ‘Inflation and Unemployment: A Demand Story’, presented to European Unemployment Conference, sponsored by the European Commission, at the European University Institute, Florence, November 21-22.

Mitchell, W.F. (1998a) ‘The Buffer Stock Employment Model and the Path to Full Employment’, Journal of Economic Issues, 32(2), June, 547-555.

Mitchell, W.F. (1998b) Essays on Inflation and Unemployment, PhD Thesis, University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia, February.

Mitchell, W.F. (2009) ‘On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose’, Bill Mitchell – billy blog. December 25, 2009 http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=6891

Mitchell, W.F. and Wray, L.R. (2005) ‘In Defense of Employer of Last Resort: a response to Malcolm Sawyer’, Journal of Economic Issues, XXXIX(1), 235-244.

Mitchell, W.F. and Juniper, J. (2006) ‘Towards a Spatial Keynesian macroeconomics’, in Arestis, P. and Zezza, G. (eds.) The Keynesian Legacy in Macroeconomic Modelling, Macmillan, London.

Mitchell, W.F. and Muysken, J. (2008) Full employment abandoned: shifting sands and policy failures, Aldershot, Edward Elgar.

Mosler, W.B. (1997-98) ‘Full Employment and Price Stability’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 20(2), Winter, 167-182.

Palley, T.I. (2013) ‘Money, fiscal policy, and interest rates: A critique of Modern Monetary Theory’, mimeo, January. http://www.thomaspalley.com/docs/articles/macro_theory/mmt.pdf

Palley, T.I. (2014) ‘Modern money theory (MMT): the emperor still has no clothes’, mimeo, February. http://www.thomaspalley.com/docs/articles/macro_theory/mmt_response_to_wray.pdf

Sawyer, M. (2003) ‘Employer of Last Resort: Could It Deliver Full Employment and Price Stability?’, Journal of Economic Issues, 37(4), December, 881-907.

Wren-Lewis, S (2016a) ‘MMT: not so modern’, Mainly macro blog, March 16, 2016, https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com.au/2016/03/mmt-not-so-modern.html

Wren-Lewis, S (2016b) ‘MMT and mainstream macro ‘, Mainly macro blog, March 22, 2016, https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com.au/2016/03/mmt-and-mainstream-macro.html

Krugman, P. (2011) ‘MMT, Again’, New York Times, August 15, 2011 – http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/15/mmt-again/.

Wray, L.R. (1998) Understanding Modern Money, Vermont, Edward Elgar.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home