有効需要=消費+投資

| / _総需要

総| A/_ー

需| 有/ー

要| _ー|投 _消費

| _ー/ |資_ー

| _ー / 効_ー

| _ー / _ー|

| _ー /_ー |消

|ー /ー 需|

| _ー |

| _ー/ |費

|ー / 用|

| / |

|/45度_______|_______

↑ 総生産、供給(GDP)

NAMs出版プロジェクト: 複数均衡 Multiple equilibria

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2017/12/multiple-equilibria.html@

複数均衡と財政政策(解説)

http://agora-web.jp/archives/1478722.html…

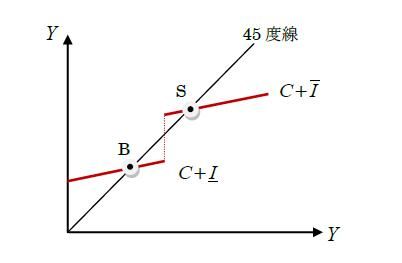

これに対して、民間投資Iの値が経済活動規模Yと関連している場合を考えてみる。例えば、簡単化のために、民間の企業は経済活動の水準がある閾値未満のときには、あまり投資をしても無駄になると考え、低水準の投資しかしないとし、経済活動の水準がある閾値以上のときには、大いに投資する意味があると考え、高水準の投資をするとしよう。

すると、次の図3のように点Bと点Sで示される2つの均衡が存在することになる。いわば、点Bは「弱気均衡」であり、点Sは「強気均衡」だといえる。そして、いま経済が点Bの状態にあったとする。この状態は悪い均衡であるが、安定した状態であり、内発的にこの状態から脱却する力は作用しない。

有効需要=消費+投資

| / _C+I'

総| /_ー

需| S/ー

要| _ー

| _ー/

| _ー /

| \ /

| /_ー

| B/ー

| _ー

| _ー/

|ー /

| /

|/45度______________

総生産、供給(GDP)

| B/ー

| _ー

| _ー/

|ー /

| /

|/45度______________

総生産、供給(GDP)

有効需要=消費+投資

| / _C+I'

総| /_ー

需| S/ー

要| _ー

| _ー/

| \/

| /\

| /_ー

| B/ー C+I,

| _ー

| _ー/

|ー /

| /

|/45度______________

総生産、供給(GDP)

| B/ー C+I,

| _ー

| _ー/

|ー /

| /

|/45度______________

総生産、供給(GDP)

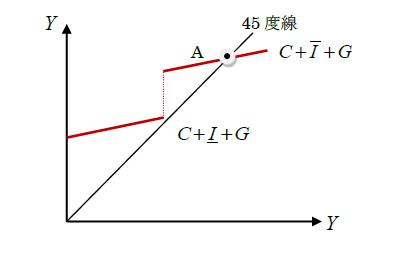

そこで、政府が支出を拡大して需要を一時的に高めて、次の図4のような状況をもたらしたとすると、経済は点Aに対応する均衡に移動することになる。

このとき、政府が支出を止めても、経済は図4の点Aから図3の点Sに移ることになるだけで、点Bの悪い均衡に戻ることはない。経済は良い均衡にとどまり続けることになる。政府支出は一時的なものであっても、悪い均衡からの脱却を促す起爆剤として働くことになり、意義があるといえる(こうした説明の仕方は、経緯は忘れたが、私は奥野正寛先生から最初に聞いた)。

このように積極的財政政策に意味があるかどうかは、単一均衡にあるのか、複数均衡のうちの悪い均衡にあるかによって違ってくる。経済が単一均衡にあるか、複数均衡のうちの良い均衡に既にある場合には、財政出動に意義は乏しいといえる。

マクロ経済学の教科書には、上記の数式が掲載されていて、「マネタリーベースをほぼコントロール下におく中央銀行は、このコントロールによって、間接的にマネーサプライを調節することができる」と解説されている。マネタリーベースは政府が採用している金融政策を判断するためのひとつの指標と見なされている。[要出典]

ただし、中央銀行がマネタリーベースでマネーサプライを調節できるかについては昔から議論があり、はっきりした結論は出ていない。日本では1970年代に日本銀行と小宮隆太郎や堀内昭義の間で論争になり、1990年代には日本銀行の翁邦雄と経済学者の岩田規久男の間で論争になった。

この論争は2010年代でも続いており、伊藤修はマネタリーベースとマネーサプライの比例関係が現実を反映していないと指摘した。

The Quality of Public Investment Shankha Chakraborty and Era DablaNorris 2009:

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Multiple-Equilibria-in-Corruption_fig1_46433387

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2009/wp09154.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shankha_Chakraborty/publication/46433387/figure/fig1/AS:306103373058051@1449992139229/Multiple-Equilibria-in-Corruption.png

松島論考より(後述):

労働供給曲線

http://nam-students.blogspot.com/2018/08/blog-post_7.html

経済学の潮流

http://www.meti.go.jp/meti_lib/report/2015fy/000336.pdf

特に、日本のデフレ不況と、そこからの脱却を考える上ではBenhabib et al. (2001)の「低い定常状態」と「高い定常状態」が発生している複数均衡モデルが有益である。 これらが取り込まれた背景を知る上では、既存のDSGEモデルに対する批判を把握しておくことで、発展形DSGEの意義を確認しやすい。

Benhabib, Jess, Stephanie Schmitt-Grohe, and Martin Uribe. 2001. "Monetary Policy and Multiple Equilibria." American Economic Review, 91(1): 167-186.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a8c0/66aa57c4649e2a58eed322de304f81089627.pdf

ベンハビブ他「流動性の罠の回避」JPE 2002 - リフレーションに関連する海外記事および論文集

https://www29.atwiki.jp/nightintunisia/pages/26.htmlAvoiding Liquidity Traps

Jess Benhabib

Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé

Martín Uribe

Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé

Martín Uribe

名目金利のゼロ下限を考慮に入れるとテイラータイプの金利フィードバックルールは意図せぬ自己充足的に減速的なインフレ経路をもたらし、予想のいかなるの見直しによってもマクロ変動をもたらす。これらの望まれぬ均衡は流動性の罠の本質的な特徴を表している。なぜなら、金融政策は産出と物価の安定に関する政府の目標の実現に置いて機能しないからである。この論文ではテイラールールの望ましい特徴---インフレ目標近傍での均衡の局所一意性など---を保存し、流動性の罠へと誘う収縮的な予想形成を排除するようないくつかの財政及び金融政策を提示する。

I. Introduction

近年、金利フィードバックルールの形態をとる金融政策のマクロ経済的帰結を研究する実証及び理論的研究が復活している。この再注目の原動力の一つは過去20年間に渡ってアメリカがそのようなルールに従っていると上手く説明できるという実証研究に見いだすことができる。具体的には、大きな影響を与えた Talyer (1993) が、インフレ率と産出ギャップにそれぞれ1.5と0.5の係数をかけて足し合わせた一次式として政策金利を設定するシンプルなルールに従うものとして連邦準備を特徴づけた。テイラールールはおおまかにいってインフレ率の上昇に対して中央銀行が金利を上げることを意味する、1より大きいインフレ率への係数の役割を安定化の重要な役割として強調した。彼のこの独創的な論文以降、この特徴を持つ金利フィードバックルールはテイラールールとして知られるようになった。テイラールールは他の先進国の金融政策の適切な説明になっていることも示されている(例えば、Clarida, Galí, and Gertler 1998 を見よ)。

同時に、理論的研究の蓄積によってテイラールールはマクロ経済の安定に貢献したことが明らかになってきた。研究者達は異なる道を辿ってこの結論に達した。例えば、Levin, Wieland, and Williams (1999) は非最適化の合理期待モデルを用いてテイラールールがインフレ率と産出の目標レベルからの乖離の損失2次関数を最小化する、という意味において最適な金利フィードバックルールであることを示した。Rotemberg and Woodford (1999) は動学最適一般均衡モデルと政策評価のための厚生条件を用いて同じような結論に達した。Leeper (1991), Bernanke and Woodford (1997), and Clarida et al. (2000) はテイラールールがマクロ経済の安定に貢献したと論じている。なぜなら、テイラールールは合理期待均衡の一意性を保証しているからである。他方で、受動的金融政策としても知られる、1よりも小さいインフレ率係数を持つ金利フィードバックルールは経済を不安定にすることを示した。なぜならそれは均衡を不決定にし、期待主導的な変動を許すからである。

方法論的に多様な研究の中でも二つの重要な要素は共有されている。一つはインフレターゲットレベル周辺の局所的な動学または小さな変動に関心を制限していること。もう一つは名目金利の下限がゼロに制約されているという事実を考慮に入れていないことである。これらの二つの単純化はマクロ経済の安定に関する重要な結果をもたらしている。

名目金利のゼロ下限と大局的な均衡動学が考慮に入れられた時に起こる問題の本質は次の二つのシンプルな関係を考えることで明確にすることが出来る。一つ目は名目金利 がインフレ率

がインフレ率 の非負増加関数

の非負増加関数 として表される金利フィードバックルールである。二つ目は定常状態でのフィッシャー方程式

として表される金利フィードバックルールである。二つ目は定常状態でのフィッシャー方程式 である。これは名目金利が実質金利

である。これは名目金利が実質金利 とインフレ率

とインフレ率 の合計と等しくならなければならないことを要求している(図1を見よ)。

の合計と等しくならなければならないことを要求している(図1を見よ)。

ターゲットインフレ率 で金融当局が

で金融当局が という意味でのテイラールールタイプの、またはアクティブな、金利政策に従っていたとしよう)。このとき、名目金利のゼロ下限の存在と金利ルールがインフレ率の増加関数であるという仮定から明らかに二つ目のフィードバックルールとフィッシャー方程式が交差するインフレ率

という意味でのテイラールールタイプの、またはアクティブな、金利政策に従っていたとしよう)。このとき、名目金利のゼロ下限の存在と金利ルールがインフレ率の増加関数であるという仮定から明らかに二つ目のフィードバックルールとフィッシャー方程式が交差するインフレ率 が存在することがわかる。この二つ目の交差点でインフレ率は低位、場合によっては負の値をとり、名目金利も低位、場合によってはゼロ、になり、金融政策は

が存在することがわかる。この二つ目の交差点でインフレ率は低位、場合によっては負の値をとり、名目金利も低位、場合によってはゼロ、になり、金融政策は という意味でパッシブになる。Benhabib, Schmitt-Grohé , and Uribe (2001b)で、我々はDGEモデルの文脈で名目硬直性の有無にかかわらず意図せざる定常状態

という意味でパッシブになる。Benhabib, Schmitt-Grohé , and Uribe (2001b)で、我々はDGEモデルの文脈で名目硬直性の有無にかかわらず意図せざる定常状態 は局所的に不定であることを示した。その近傍においてインフレ率、金利、マクロ経済が予想の非ファンダメンタルな見直しに反応して変動するような均衡が存在する。より重要なことに、二つ目の定常状態はターゲットであるインフレ率

は局所的に不定であることを示した。その近傍においてインフレ率、金利、マクロ経済が予想の非ファンダメンタルな見直しに反応して変動するような均衡が存在する。より重要なことに、二つ目の定常状態はターゲットであるインフレ率 のどれだけ近くからスタートしても

のどれだけ近くからスタートしても に収束してしまうような均衡経路の存在を引き起こしてしまう。

に収束してしまうような均衡経路の存在を引き起こしてしまう。

経済がこのようなタイプの減速するインフレ動学に陥ると、場合によっては物価と産出の安定という政府のゴールを達成するための金融政策が無効になってしまうような負のインフレ率とゼロ金利の状態の向かっていってしまう。このような状態は、物価の下落に際して金利を比し下げることで金融緩和を行うというタイプの金融政策を行う中央銀行が無力になるという流動性の罠の本質的な性質を全て備えている。

この論文の中心的な問題意識はテイラールールの有効性を保ち、ターゲットのインフレ率と産出レベルの近傍で望ましい全ての局所的性質を備え、同時に流動性の罠へと導くような均衡動学を排除する財政・金融政策のデザインにある。

流動性の縄を避けるための大きく分けて二つの方法を示す。一つ目のものでは、流動性の罠は金融政策がいつでも金利ルールに従うという条件の下での財政政策によって排除される。提示される安定化政策はインフレ率が低下し始めると自動的に発動される強い財政刺激を特徴とする。特に、財政ルールはインフレが落ちつくと税率を下げるインフレ率に感応的な予算スケージュールとなる。経済が流動性の罠に近づくにつれ、財政赤字は低インフレ定常状態が財政的に持続不可能となり、合理期待均衡として支持されなくなるほど大きなものになる。財政的に持続不可能にすることで流動性の罠の均衡を排除するというアイディアの基本的な洞察はWoodford (1999) による。

よって、流動性の罠を避ける最初の我々の方法は最近の---特に米財務省から出されている---政策提案を理論的に支持するものである。これは既に名目金利がゼロに近いため金融政策の余地がないような国---たとえば日本---は流動性の罠を抜けるために財政支出を行うべきという提案である。しかし、我々はまったく異なる理由からこの政策を推薦する。財政政策は通常いわれるような乗数効果を通じてではなく、むしろ政府の動学的予算制約への効果を通じて流動性の罠を排除するのである。流動性の罠を排除するチャンネルはピグーが論じた流動性の罠の非現実性に関する議論とむしろ同種のものである。閉鎖経済においては、政府の動学予算制約は代表的家計の動学予算制約の鏡像である。減税は家計の可処分所得を増加させる。これによって財に対する超過需要が生まれる。結果として、物価は財市場の均衡を回復するため上昇しなければならない。

二番目の方法は金利ルールから貨幣成長ルールへの変更が自己充足的なデフレ経路を断つというものである。この代替案は人気があって、政策論争において良く言及される。低インフレ均衡(またはデフレ均衡)に陥ったときには政府は経済をジャンプスタートさせるために単に貨幣を刷れば良いのである。例えば Krugman (1998) は日本の現在の不況から救い出すための方法としてこのタイプの政策を力強く主張する。しかしこの提案は通常付随する財政政策には触れずに行われる。Woodford (1999) にあるように、貨幣成長率ルールは「正しい」財政政策と組み合わされた時のみに、流動性の罠の回避および脱出に有効な手段となる。例えば、貨幣成長ルールに変更された時に採用されている財政政策レジームがあらゆる場面で財政の持続性が保証されているものならば、貨幣の増刷はむしろデフレスパイラルを加速させる反生産的なものになってしまうのだ。一般的に言って、貨幣成長率ルールへの変更を成功させるポイントは名目金利がゼロに向かうにつれ政府の動学予算が債務不履行に向かうような財政政策を伴うことである。

この論文の残りは5つの節からなっている。第II節はモデルと基本となる金融・財政政策レジームを提示する。第III節では均衡の局所的な振る舞いを考察する。第IV節では金融政策がテイラールールタイプの金利フィードバックルールを採用しているときに、経済がどのようにして流動性の罠に陥るかを明らかにする。第V節と第VI節では流動性の罠均衡を排除する財政・金融政策で用いられる手法について論じる。第VII節ではこの論文の結論を述べる。そこでは名目硬直性や時間の離散的な扱い、流動性の罠を避ける方法として関連する研究で示唆されているGesell税を適用した場合などを取り入れたモデルに対する本論の結果の頑健性を示す。

VII. Discussion and Conclusion

名目金利のゼロ下限は金利フィードバックルールの形をとる金融政策を採用している経済を意図せざる均衡へと導きやすくさせる。このような望ましくない状況が発生すると、金融当局は政府の目的を達成することができなくなる。インフレ率や産出と物価の変動などの重要なマクロ経済変数に影響を与えることができないという、まさに流動性の罠の本質が現れるのである。

名目金利のゼロ下限の明示的な考慮を別にすれば、我々のモデルとテイラールールの望ましさを強調するモデルとの顕著な違いは名目変数の伸縮性にある。しかしながら、テイラールールタイプの政策の結果として流動性の罠へ陥る可能性はこの論文で示されたシンプルな伸縮的環境に限定されない。Benhabib et al. (2001b) で我々はテイラールールが価格調整が粘着的な環境でも流動性の罠を生じさせることを示した。このタイプのモデルでは、流動性の罠は本論文で示されたようなインフレ率と実質貨幣残高の不定性だけでなく、総需要の水準も不定になる。第V節と第VI節で示した流動性の罠を根絶するための政策は粘着価格の場合でも効果がある。なぜならばそれらの提案は経済が流動性の罠に落ちるような時には横断性条件を満たさなくなるようなものだからだ。長期的な制約の違反は短期の名目価格の硬直性とは独立なモデルの内生変数の非対称的な行動に依存しているのだ。

この論文と関連した研究での理論的な環境のさらなる違いは時間を連続変数として扱っていることにある。繰り返しになるが、テイラールールを適用することで持ち上がる流動性の罠の存在や提案された救済方法の効果はいずれも重要ないかなる点においてもこの仮定によって変わるものではない。Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe (2000) は現金と信用財を使った離散時間におけるキャッシュインアドバンスモデルを分析して、名目金利に下限がある場合にはテイラールールは意図せざる流動性の罠の問題を生じさせることを示した。この望ましからぬ均衡の本質は、本論で述べられたものと同一のものである。連続時間のモデルで流動性の罠を回避させる長期的な制約は離散時間でも適用可能である。

本論文で考察された政策はテイラールールの下で発生する悪性な動学を排除することを意図したものと見ることができる。これらの政策が効果を持つためには、悪性動学の下ではインフレ率は意図したターゲットから永久に離れ続けることが重要である。Benhabib et al. (2000) で我々は本論で考察したものとは別の本質を持つ意図せざる動学をテイラールールが生じさせることを示した。これらの動学の下では、中央銀行が意図した均衡の近傍---潜在的にはかなり「広い」近傍---で変動するものの、本論で考察したような自己充足的なデフレや、もしくは流動性の罠に陥ることはない。よって、インフレ率が恒久的に低位に収束することに依存しているために本論で説明した特定の政策はカオス的な均衡を排除できないかもしれない。

Buiter and Panigirtzoglou (1999) はGesell税(貨幣保有への課税)を流動性の罠の回避方法として提案している。Gesell税は貨幣へのマイナス金利と考えることができる。貨幣保有の機会費用は債券の名目金利と貨幣の差として与えられるため、Gesell税は政府証券の名目金利をマイナスにすることで貨幣保有の機会費用をプラスにすることが出来るのだ。よって、流動性の罠が貨幣の保有コストがゼロになることと解釈するならばGesell税は流動性の罠を排除することにはならないことは明らかであり、単に債券の名目金利をゼロ以下に押し下げるだけである。流動性の罠に陥る可能性として重要なことは名目金利の(ゼロとは限らない)下限が存在するときのテイラールールタイプの金利ルールの組み合わせなのだ。この下限がプラスであろうとマイナスであろうゼロであろうと関係はないのだ。

References

- Benhabib, Jess; Schmitt-Grohe´ , Stephanie; and Uribe, Martín. “Chaotic Interest Rate Rules.” Manuscript. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania, Dept. Econ., 2000.

- ———. “Monetary Policy and Multiple Equilibria.” A.E.R. 91 (March 2001): 167–86. (a)

- ———. “The Perils of Taylor Rules.” J. Econ. Theor y 96 ( January/February 2001): 40–69. (b)

- Bernanke, Ben S., and Woodford, Michael. “Inflation Forecasts and Monetary Policy.” J. Money, Credit and Banking 29, no. 4, pt. 2 (November 1997): 653–84.

- Brock, William A. “Money and Growth: The Case of Long Run Per fect Foresight.” Internat. Econ. Rev. 15 (October 1974): 750–77.

- ———. “A Simple Per fect Foresight Monetary Model.” J. Monetar y Econ. 1 (April 1975): 133–50.

- Buiter, Willem, and Panigirtzoglou, Nikolaos. “Liquidity Traps: How to Avoid Them and How to Escape Them.” Discussion Paper no. 2203. London: Centre Econ. Policy Res., August 1999.

- Clarida, Richard H.; Galí, Jordi; and Gertler, Mark. “Monetary Policy Rules in Practice: Some International Evidence.” European Econ. Rev. 42 ( June 1998): 1033–67.

- ———. “Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Evidence and Some Theory.” Q.J.E. 115 (February 2000): 147–80.

- Fuhrer, Jeffrey C., and Madigan, Brian F. “Monetary Policy When Interest Rates Are Bounded at Zero.” Rev. Econ. and Statis. 79 (November 1997): 573–85.

- Krugman, Paul R. “It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap.” Brookings Papers Econ. Activity, no. 2 (1998), pp. 137–87.

- Leeper, Eric M. “Equilibria under ‘Active’ and ‘Passive’ Monetary and Fiscal Policies.” J. Monetar y Econ. 27 (February 1991): 129–47.

- Levin, Andrew; Wieland, Volker; and Williams, John C. “Robustness of Simple Policy Rules under Model Uncertainty.” In Monetar y Policy Rules, edited by John B. Taylor. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press (for NBER), 1999.

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. “Money Demand in the United States: A Quantitative Review.” Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy 29 (Autumn 1988): 137–67.

- Obstfeld, Maurice, and Rogoff, Kenneth. “Speculative Hyperinflations in Maximizing Models: Can We Rule Them Out?” J.P.E. 91 (August 1983): 675–87.

- Orphanides, Athanasios, and Wieland, Volker. “Price Stability and Monetary

- Policy Effectiveness When Nominal Interest Rates Are Bounded at Zero.” Finance and Economic Discussion Series, no. 98-35. Washington: Board Governors, Fed. Reserve System, June 1998.

- Reifschneider, David, and Williams, John C. “Three Lessons for Monetary Policy in a Low Inflation Era.” Finance and Economic Discussion Series, no. 99-44. Washington: Board Governors, Fed. Reserve System, August 1999.

- Rotemberg, Julio, and Woodford, Michael. “Interest Rate Rules in an Estimated Sticky Price Model.” In Monetar y Policy Rules, edited by John B. Taylor. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press (for NBER), 1999.

- Schmitt-Grohé , Stephanie, and Uribe, Martıín. “Price Level Determinacy andMonetary Policy under a Balanced-Budget Requirement.” J. Monetar y Econ. 45 (February 2000): 211–46.

- Shigoka, Tadashi. “A Note on Woodford’s Conjecture: Constructing Stationary Sunspot Equilibria in a Continuous Time Model.” J. Econ. Theor y 64 (December 1994): 531–40.

- Stock, James H., and Watson, Mark W. “A Simple Estimator of Cointegrating Vectors in Higher Order Integrated Systems.” Econometrica 61 ( July 1993): 783–820.

- Taylor, John B. “Discretion versus Rules in Practice.” Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy 39 (December 1993): 195–214.

- Wolman, Alexander L. “Real Implications of the Zero Bound on Nominal Interest Rates.” Manuscript. Richmond, Va.: Fed. Reserve Bank Richmond, December 1999.

- Woodford, Michael. “Monetary Policy and Price Level Determinacy in a Cashin-Advance Economy.” Econ. Theor y 4, no. 3 (1994): 345–80.

- ———. “Price-Level Determinacy without Control of a Monetary Aggregate.” Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy 43 (December 1995): 1–46.

- ———. “Control of the Public Debt: A Requirement for Price Stability?” Working Paper no. 5684. Cambridge, Mass.: NBER, July 1996.

- ———. “Price-Level Determination under Interest-Rate Rules.” Manuscript. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ., April 1999.

http://ikedanobuo.livedoor.biz/archives/51301089.html

2008年12月31日12:36

ケインズの葬送

『一般理論』は非常に難解な本である。脱線や重複が多く、前後で矛盾していて、統一的な理論モデルがどこにも書かれていない。これは「ケインズ・サーカス」という研究会の記録をもとに書かれ、コアになったのはリチャード・カーンの乗数理論だったので、正確にはカーンとの共著だといわれる。この研究会のメンバーだったジョーン・ロビンソンも「ひどい本だ」と評した。特に岩波文庫の訳本は、絶対に読んではいけない。

乗数については、1933年にカレツキが(ポーランド語で)発表した理論のほうが数学的に明快だ。彼が依拠しているのは新古典派ではなくマルクスで、剰余価値率(マークアップ)が一定の固定価格経済を明示的に仮定している。所得が乗数倍になるためには、所得の増加によって需要が拡大しても価格が変化しないことが必要条件だからである。カレツキは、現代社会では価格が自由に調整されるのは生鮮食料品のようなマージナルな商品で、中核となる工業製品はマークアップで価格づけされていると論じている。

同様の議論はClower-Leijonhufvudなどによって行われ、Barro-Grossmanに集大成されている。ただBarro自身がのちにこの種の不均衡理論を放棄したように、不均衡状態で価格がなぜ変化しないのかという理由がはっきりしない。新古典派的な凸の戦略空間を考えると、需給ギャップは長期的には価格で調整されて不均衡はなくなるはずだ。この点を理論的に明らかにしたのがMankiw-Romerに代表される「新ケインズ派」で、コーディネーションの失敗(非凸性)があるときは、不均衡状態がナッシュ均衡になってしまうことを明らかにした。

現状は世界規模の取り付けによってコーディネーションの失敗が生じているので、ケインズ的な状況だという理解は必ずしも間違っていない。こうした複数均衡状態では「よい均衡」の所在を知っている賢明な政府が民衆を正しい解に導くことが望ましい、というケインズの思想はマルクスと同じで、こうした計画主義が20世紀後半の経済政策を支配した。しかし問題は、政府が正しい解を知っているのかということだ。

ケインズ自身は『一般理論』の均衡理論的な解釈を否定し、大恐慌では不確実な未来についての悲観的な予想によって過少投資が起きるので、政府がリスクをとるべきだと強調した。これは意外なことに、Lucasの考え方とよく似ている。彼はWSJに寄稿したエッセイで、FRBがリスク資産を買う非伝統的な金融政策は、従来の意味での金融政策というより、政府部門がリスクを負担して「悪い均衡」を脱却する政策だと理解している。

ただ悪い均衡を脱却しても、実際の戦略空間は非常に複雑なので、どこによい均衡があるかは誰にもわからない。もちろん政府が知っているとも限らない。したがって政府が特定の部門に裁量的に支出して、よい均衡に導こうとするケインズ政策は、有害無益な浪費に終わることが多い。悪い均衡を脱却したあとは、民間の経済主体が自律分散的にリスクをとって新しい均衡をさがすしかない。

こういうコーディネーションの問題を、集計的な総需要の不足として表現したケインズの理論は、彼の時代にはやむをえなかったとはいえ、きわめてミスリーディングなものだ。「需要が不足している」という話は、なぜ不足しているのか、そして不足がなぜ価格で調整されないのかを明らかにしないかぎり、説明にはならない。だからケインズの診断は正しかったが、その学問的表現は誤っており、不均衡状態を政府が解決できるという彼の処方箋は、社会主義に代わってパターナリズムの温床になった。彼をつつしんで葬送し、21世紀にふさわしい処方箋を考えることが、われわれの仕事だろう。

_____

Mill, Principles of Political Economy, Book III, Chapter XVIII 1848

http://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/mlP47.html

複数均衡のアイデアは上記のミルからマーシャルが示唆を受けて以下で説明した

Early Economic Writings, 1867-90 - 149 ページ

John K. Whitaker, Alfred Marshall - 1975[1920]

邦訳32-5頁:

外國貿易の純粹理論

一つの例外の場合に關するミルの所論に對する覺書

ミルは、〔經濟學原理〕第三編第十八章第六節[譯註][岩波文庫③302~4頁☆]において、外國貿易論に關する諸困難を論じよう

と試みてゐるが、その一つの解決法については、本書においては、第一種の檢討として論じておいた。

ミルのみるところによれば、、一定の情況においては數個の異れる貿易均衡點があり得、したがってこれ

らの均衡點のどこで貿易が停止するか、といふことを決定する

問題が生ずる。ミルは一例をあげて、この一般的なる問題を解

圖くべき方法を例示しようと、試みた。しかし私のみるところに

よれば、ミルが選んだ特別の例は、當面の一般問題を例示して

ゐない。何となれば私の理解するところによれば、ミルの見解

は次の如くであるからである。イギリスがリンネルの購買に費

す羅紗の量は、交換比率の如何にかかはらず一定の數量例へば

OVであり、またドイツが羅紗購入のために喜んで費さんとす

るリンネルの量は、一定の數量例へばOWである。この假設によれば、貿易は唯一つの可能的均衡點を

もつのみであり、それは卽ち羅紗OVがリンネルOWと交換される點である。貿易から生ずる全部利益

が兩國の間に分配される仕方は、OV及びOWの相對量に依存する、といふことをミルは證明したが

それは勿論自明の理である。

〔譯註〕

〔この第六節は『經濟學原理』第三版一八五二年刊に至って補入された。本文においてマーシアルにより『ミルが

選んだ特別の例は當而の一般問題を例示してゐない』と批評された『特別の例』とは、次の如きものである。

『以上の國際價值論は、本書の第一版ならびに第二版において述べたところのものである。しかるに頴敏なる諸の批評

(主として友人ウヰリアム·ソーントン氏の批評)を受けかつその後さらに檢討を加へた結果、上段に述べた學說は、その

所說のかぎりにおいては正當ではあるが、本問題の理論としては未だ完璧ではない、といふことが明かとなった。

『卽ち次のことが明かとなったのである。二國間の(あるひは二國以上を想定すれば、各一國と世界との間の)輸出と

輸入とは、全體として相償はねばならず、したがって兩者は國際需要の均等と兩立し得べき價值において相交換されねば

ならない。しかしこのことは、現象の法則として完全なものでないことは、次の考察によって知られるであらう。卽ち、

この法則の諸條件をいづれも同等に滿足すべき國際價値の割合は、幾通りもあり得るのである。

『これまでの想定は、次の如くであった。羅紗十ヤールを生産するに、イギリスはリンネル十五ヤールにあたる勞働を、

ドイツはリンネル二十ヤールにあたる勞働を必要とする。兩國の間に貿易が開かれる。爾來、イギリスは羅紗の生産のみ

に、ドイツはリンネルの生産のみに沒頭する。そこでもし爾來羅紗十ヤールとリンネル十七ヤールとが交換さるべきもの

とすれば、イギリスとドイツとは正にその需要を相充たすであらう。例へばこの價格においてイギリスが一萬七千ヤール

のリンネルを求めるとすれば、ドイツは丁度羅紗一萬ヤールを求め、イギリスはこの羅紗をこの價格においてリンネルの

代りに與へなければならないであらう。これらの想定の下において、十ヤールの羅紗對十七ヤールのリンネルは、事實上、

國際價值たるべきことが判明するのである。

『しかしある他の比率、たとへば十ヤールの羅紗對十八ヤールのリンネルの如きも、同じく國際需要の均等といふ條件

を滿足すべきことも充分可能である。例へば次の如く假定せよ。この後の比率においてイギリスは十對十七の比率におけ

るときよりもより多くのリンネルを求め、しかもその增加率が價格低下率に比例しないものとする。卽ちイギリスはい未

や一萬ヤールの羅紗をもって一萬八千ヤールのリンネルを購買し得るにもかかはらず、これだけを求めずして一萬七千五

百ヤールをもって滿足し、その代りとして九千七百二十二ヤールの羅紗(新しき比率たる十對十八において)を支拂ふの

である。なほまたドイツは、十對十七において購買し得た場合よりも羅紗に對しより高價を支拂はねばならないから恐ら

くはその消費を一萬ヤール以下の分量に減少せしめる、自ち多分丁度上にあげた數量九千七百二十二ヤールとするであら

う。これらの條件の下においても、國際需要の均等はやはり存在するであらう。かくて十對十七の比率及び十對十八の比

率が同等に需要の均等を滿足するのである。そしてその他の交換比率にして同樣にこれを滿足するものも數多くあるであ

らう。およそ想定し得べきあらゆる數字上の比率が同等に上の條件を滿足すべきことさへ、考へることもできる。したが

って國際價値がみづから調整して定まるべき比率には、いまだなほ不確定なる部分が存在し、問題に影響する諸事情の全

部が必ずしもすべて考慮に入れられてゐなかったことを、示すのである.〕

ミルの例解は、圖形で示せば次の如くとなるであらう。Ox及びOyと直角にそれぞれびPQ及びW

RSを描き、Aにおいて交はらしめよ(第六圖)。イギリスが、羅紗OVを生産し輸出するために費すべ

失費をもって、みづから生産し得べきリンネルの量を、VPとする。しからばPQはイギリスの需要

曲線の一部であり、この場合には(數學上の言葉でいへば)『高等な曲線が特に直線こなってゐる』の

である。同樣にして、もしドイツが、リンネル品を生産し輸出するために費すべき失費をもって、み

づから生産し得べき,羅紗〔譯註〕の分量を、WRとすれば、その場合RSはドイツの需要曲線の一部であ

る。これら二つの直線PQ及びRSは、一つ以上の點において交はることはできない。したがってミル

の例は、第四圖における兩曲線の諸交點によって暗示せられてゐるかの種の問題の解決には、何等の助

けをも與へない。兩國間の貿易から生ずる利益の分配に關しては、AとPとが合致すれば、イギリスは

輸入リンネルに對しみづから生産するとき用費せらるべき額と全く同額を支拂はねばならず、したがっ

てイギリスは貿易から何の利益をも得ないことを、注意すべきである。同様にしてAがRと合致すれば、

ドイツは貿易から何の利益をも得ないであらう。AがPの上方にあればあるほど、イギリスが貿易から

得べき利益は大となり、AがRの右方にあればあるほどドイツが貿易から得べき利益は大となる。勿論

この問題の條件からいって、AがPの下方に橫はり、またはRの左方に橫はることは、あり得ないのであ

る。

外國貿易の純粹理論

☆

第三篇

第十八章 国際的価値

六

〔上記の理論は完全でない]

この著書の第一版および第二版に含まれていた国際的価値の理論は、上記のところだけであっ

た。しかしその後種々聡明な批評を(主として私の友人ウィリアム·ソーントン氏の批評を)受け、

またそれに基づいてさらに研究を進めた結果、右に記した学説は、それ自身としては正しい学説

であるが、しかしこの問題に関する理論としては完全無欠なものでないということが、明らかと

なった。

さきに明らかにしたように、二国間の(あるいはもしも二国以上の国を仮定するならば、それぞ

れの国と世界とのあいだの)輸出と輸入とは,全体として相互に対する支払いとならなければな

らず、したがって国際的需要の方程式の条件を満たすべき価値をもって互いに交換されなければ

ならない。しかしこれはこの現象に関する完全な法則でない。このことは,すべてひとしくこの

法則の諸条件を満たしうる国際的価値のいくつかの相異なった比率がいくつもある、ということ

を考慮すれば明らかである。

私たちは次のように仮定していた。すなわちイギリスは十ヤールのラシャを十五ヤールのリン

ネルと同じ量の労働をもって生産し、ドイツはそれを二十ヤールのリンネルと同じ量の労働をも

って生産する。そしてこの二国のあいだに貿易が開かれ、それ以降イギリスはその生産をラシャ

に限り、ドイツはリンネルに限るが、もしもその後十ヤールのラシャがリンネル十七ヤールと交

換されるようになれば、イギリスとドイツとは互いに相手国の需要を過不足なしに満たすであろ

う。すなわちたとえばイギリスが右の価格においては一万七千ヤールのリンネルをほしいと思っ

たとすれば、ドイツはまさしく一万ヤールのラシャをほしいと思い、しかもこのラシャの量は、

イギリスが、右の価格において、リンネルの代価として提供しなければならぬものであろう、と

である。このような仮定のもとでは、十ヤールのラシャ対十七ヤールのリンネルという割合が実

際上国際的価値となるであろうことは明らかである。

けれども、たとえば十ヤールのラシャ対十八ヤールのリンネルというような、これ以外のある

比率が、ひとしく国際的需要の方程式の諸条件を満たしうる、ということも十分にありうること

である。いま次のように仮定しよう。すなわちこの最後の比率においては、イギリスは十対十七

という比率のときよりもより多量のリンネルをほしいと思うが、ただし低廉化に比例してではな

いと。すなわちイギリスはいまや一万ヤールのラシャをもって一万八千ヤールのリンネルを購入

しうるが、一万八千ヤールをほしいとは思わず、一万七千五百ヤールをもって満足し、これに対

し(十対十八という新しい比率において)九千七百二十二ヤールのラシャを支払うと。またドイツ

は、ラシャ に対し、十対十七の比率をもって購入することができたときよりも高い代価を支払わ

なければならないので、おそらくその消費を一万ヤール以下のある分量~おそらく右と同じ九

千七百二十二ヤールという分量~に削減するであろう。このような条件のもとでも、『国際的

需要の方程式』はなお存立するであろう。したがって、十対十七という比率と十対十八という比

率とは、ともにひとしく『需要の方程式』を満足させるであろう。またこれ以外の数多くある交

易比率も同じようにそれを満足させるであろう。いかなる数字上の比率を仮定しても、それはひ

としく右の条件を満足させるとも考えられる。したがって、国際的価値が自らを調整するところ

の比率には、なお一片の不確定なるものが残っているわけであって、このことは、事柄に影響を

与える事情のうち、なおまだ考慮されていないものがあるに相違ない、ということを示している。

〔1〕この第六節から第八節京での三節は第三版(一八五二年刊)において書き加えられたものである。

_____

History Versus Expectations Paul Krugman The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 106, No. 2. (May, 1991), pp. 651-667.

https://www.isid.ac.in/~tridip/Teaching/DevEco/Readings/03Expectations/06Krugman-QJE1991.pdf

参考:

Ethier, Wilfred, "Decreasing Costs in International Trade and Frank Graham's Argument for Protection," Econometrics, L (1982a1, 1243-68.

ー -, "National and International Returns to Scale in the Modern Theory of International Trade," American Economic Review, LXXII (1982b),389-405.

Matsuyama, Kiminori, 松山公紀

"A Theory of Sectoral Adjustment," Northwestern Univer- sity discussion paper #812, 1988.

-, "Increasing Returns, Industrialization, and Indeterminacy of Equilibrium," Quarterly Journal of Economics, CVI (1991),617-50.

NAMs出版プロジェクト: 情報の非対称性 スティグリッツ

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2016/04/blog-post_0.html

http://library.jsce.or.jp/jsce/open/00039/200806_no37/pdf/181.pdf

社会実験を通じた複数均衡解をもつモデルの推定法 É An Estimation Method of Models with Multiple Equilibria by Using the Result of Social ExperimentationÉ 1. はじめに市場に参加する個人が行動を互いに調整することにより,より効率的な均衡解が実現する場合,当該個人の戦略の間に戦略的補完性が存在する1)という.戦略的補完性が機能する市場においては,複数均衡が生じうる.複数均衡のうちのパレート劣位な均衡にロックインされている場合,市場メカニズムを通じてパレート劣位の均衡から優位の均衡へ移動するのは難しい.異なる均衡間の移動をもたらすためには,社会実験等により強制的に状態を変化させる必要がある.したがって,複数均衡解の存在を実証的に分析し政策論につなげるためには,社会実験を通じてその効果を検証することが必要不可欠であるが,その方法論については未だ検討すべき点が多い.本研究では,社会実験の結果を用いて,複数均衡が存在する場合のモデルの推計方法について検討する.松島格也ÉÉ

Cooper, R. and J. Andrew: Coordinating Coordination Failures in Keynesian Models, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 103, pp. 441-463, 1988.

マーシャル

https://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/contentscinii_20171229080626.pdf?id=ART0010171465

マーシャル的収穫逓増による貿易パターンと貿易利益1)2)

(Adobe PDF)

ci.nii.ac.jp/lognavi?name=nels&lang=en&type...

収穫逓増産業が貿易パターンと貿易利益に与える影響を議論する貿易モデルの 1 つに 、マーシャル. 的収穫逓増を含む 2 国 2 財 1 生産要素モデルがある。その代表的な 先行研究 ... きさの程度によって、複数個の異なる貿易パターンの貿易均衡が得られる ことを明らかにしている。 また、小国において、貿易の開始によって収穫逓増財の生産 が縮小した場合に、貿易 ...... First, we search the necessary condition of multiple trade equilibria for the patterns of trade with Ethiers allocation curves, and modify the λ-μ ...

複数均衡 Multiple equilibriaをマーシャルに示唆したのはミルらしい

マルクス再生産表式も単純と拡大の二つの均衡を示唆する

その後、パレート、ナッシュ、ゲーム理論、行動経済学が意味を解明した

ラムゼー(課税)、ソロー(成長)も重要

利得表

payoff mtrixを使うとわかりやすい

永田論考

http://naosite.lb.nagasaki-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/10069/6264/1/KJ00004125777.pdf

ところで、オファー。カーブは、ほんらい、マーシャル自身により、かれの著作[7]や[8〕で利用されているように、2人の個人を2国に読み替えることによって、国際貿易論における交易条件の決定問題に利用されている】3'。そのさい、マーシャル自身は、いわゆる「相互需要説」にもとづく交易条件論において、ミルによる複数均衡解存在の可能性への指摘にインスパイアされて、オファー。カーブを考案したl`l'。さらに、そのミルは、

リカードゥの比較生産費の原理における交易条件の未決定問題にメスを入れることから出発している15)。本稿で検討したように、ワルラス純粋交換モデルをマーシャルの用語に翻訳したワルラシアン・オファー・カーブの議論では、マーシャル流の用語を借用すれば、取引に参加している当事者双方の需要価格が適切な初期条件をみたしていないと、均衡解が存在しなかったり、あるいは、たとえ存在したとしても、ゼロ数量の均衡をもたらしたりする可能性がある。これらのケースは、国際貿易論の用語に翻訳すれば、じつは、比較優位が運転したり、あるいは、それらがまったく一致したりするケースに相当するとおもわれる。このような、国際貿易論における、オファー・カーブと比較優位論とのあいだの関連については、別稿にゆずる。

また、本稿の冒頭の引用文では、ワル.ラスは、体系内に貨幣を導入しても、物々交換の検討で導かれた結論は、いぜんとして、そっくりそのまま妥当するという観点にたっ貨幣ベール観を表明していた。ところが、そもそも、一般的等価物としての貨幣の意義のひとつは、物々交換とは異なり、売りと買いを時間的・空間的に分離しうることにある。そうすると、貨幣経済では、供給は、かならずLも需要の鏡像として、同時に実行されることにはならない。さらに、一般的等価物としての貨幣は、他の商品所有者たちだれもが自己が所有する商品と引き換えに交換を希望する結果、どのような商品とも即時に交換可能であるという一般的使用価値を認められるために、この貨幣という、富の代表者となるべき一般的使用価値を獲得することが目的に転じて、貨幣を獲得するための手段として、需要よりもむしろ供給のほうが重要視されるような活動に転じる。いわば、物々交換の使用価値目的から、貨幣経済の交換価値目的への転回がおこなわれるのである。マルクスの用語を借用するならば、流通手段としての貨幣の存在は、使用価値の取得を目的とした単純流通Ⅳ-G-Ⅳ■のなかから、交換価値を目的とした資本としての流通G-〟-C-への転化をもたらす。その結果、もはや、需要の鏡像として供給を位置づけることはできず、ワルラスが期待するほど、単純には、貨幣経済の議論が物々交換のそれへ帰着すると、楽観視することはできない。というのも、ノガロも指摘するように、「貿易差額の均衡に関しては国際貿易は物々交換の概念に帰せしめらるゝことが出来ない。故に、リカルドの理論に交換の一般的条件の上に立つ広範なる基礎を与えむとしたミルの努力は全く徒労であって、物々交換の過程と国際貿易のそれとの間には何らの論理的関係はない」】6)のであるから。このような純粋交換モデルからの類推による国際貿易論の欠陥は、「国際価値論と国際貨幣論が、互いに交わることのない平行線の形で、論理的関係のない別々のもののように論述された」17'ことに起因する。この点にかんしては、新庄[17]で、指摘されているように、「リカードが-・結論を導出せる原因の一つには、二国間に於ける二財貨のみの交換を仮定し、従って一方からの-財貨の輸出に対し他の側からその対価として引き渡し

14)Marshall[8]参照。

[7]Marshall,A.,MoneyCreditandCommerce,Macmillan,1923;(永揮越郎訳『貨幣信用貿易(1-2)』岩波ブックサービスセンタ-,1988年)

[8]Marshall,A.,ThePureTheoryofForeignTrade,1930;(杉本栄一編『マーシャル経済学選集』日本評論社,1940年所収)

[9]Marshal

11]Mill,J.S.,EssaysonSomeUnsettledQuestionsofPoliticalEconomy,JohnW.Parker,1844;(末永茂喜訳『経済学試論集』(岩波文庫)岩波書店,1936年)

[12]Mill,J.S.,PrinciplesofPoliticalEconomywithSomeofTheirAZPPlicationstoSocialPhilos妙,1848;(末永茂喜訳『経済学原理(1-5)』(岩波文庫)岩波書店,1959-63年)

資料情報 ( 所蔵情報 | 予約情報 )

タイトル

マーシァル経済学全集x 選集○

叢書名

経済学名著選集

著者名等

マーシァル/〔著〕

著者名等

杉本栄一/編

出版者

日本評論社

出版年

1940.10

大きさ等

23cm 309,6p

注記

叢書の編纂:山田雄三,高島善哉

NDC分類

331.74

件名

経済学-ケンブリッジ学派

内容

件名索引・人名索引あり 内容:解説‐序に代えて 杉本栄一/著. 外国貿易の純粋理

論 杉本栄一/訳. 国内価値の純粋理論 中山伊知郎/訳. ジェヴォンス氏の経済学

純理 高島善哉/訳. ミル氏の価値理論 高島善哉/訳. 経済学の現状 板垣与一/

訳. 経済学者の旧世代と新世代 山田雄三/訳. 経済学における力学的類同性と生物

学的類同性 山田雄三/訳. 経済騎士道の社会的可能性 金巻賢字/訳

書誌番号

3-0192005560

複数均衡 Multiple equilibria

「複数均衡におけるアナウンスメントの役割 ~「悪い」均衡から「良い」均衡へ~」 by Olivier Blanchard – 道草

http://econdays.net/?p=8196

「複数均衡におけるアナウンスメントの役割 ~「悪い」均衡から「良い」均衡へ~」 BY OLIVIER BLANCHARD

以下は、Olivier Blanchard, “Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy”(iMFdirect, April 29, 2013)の一部抜粋訳。

<その6>目視での航海(Navigating by sight) 複数均衡とコミュニケーション(Multiple equilibria and communication)

複数均衡が成り立つ世界では、アナウンスメントは大きな重要性を持ち得る。例えば、ECBがアナウンスしたOMT(Outright Monetary Transaction;国債買い入れプログラム)のケースを考えてみてほしい。このプログラムのアナウンスメントは、ソブリン債市場において複数均衡の発生につながる源泉の一つを取り除く効果を持ったと解釈することができる。つまりは、コンバーティビリティ・リスク-投資家が「ユーロ圏周辺国はユーロから離脱するに違いない」と考えて、それら各国政府が発行する国債の購入に際してプレミアムの上乗せを要求し、その結果としてユーロ圏周辺国が実際にもユーロからの離脱を強いられることになる危険性-の除去に成功したと考えられるのである。それも実際にプログラムを実行に移す必要もなく、プログラムのアナウンスメントを通じてそのような効果が生じたのである。

この観点からすると、つい最近日本銀行が発表したアナウンスメントはなおいっそう興味深い。そのアナウンスによると、今後日本銀行はマネタリーベースを2倍に拡大する予定とのことだが、この政策がインフレに対してどの程度効果を持つかは、(この政策の結果として)家計や企業が抱くインフレ期待がどのように変化するかに大きく依存することだろう。仮にインフレ期待が上昇することになれば、家計や企業による賃金や価格の決定に影響が及び、その結果としてインフレの上昇につながることだろう。インフレの上昇はデフレ下にある日本においては望ましい結果である。一方で、インフレ期待の上昇につながらなければ、インフレが大きく上昇すると考えるに足る理由はないことになろう。

それゆえ、この劇的な金融緩和に向けた動きを支える主たる動機は、心理的なショックを与え、人々の認識と価格決定のダイナミックスにシフトを生じさせることにある、ということになろう。今回の日銀の決定は-日本の政府当局が実施するその他の政策と相伴うことで-うまく機能するだろうか? そうなることを祈ろう。しかし、(仮に日銀の政策が効果を持ったとしても)教科書で説明されているような機械的なかたちで効果を持つわけではないだろう。

05/07/2013 – 7:08 AMBy hicksianPosted in Olivier BlanchardComments (0)

http://ikedanobuo.livedoor.biz/archives/51301036.html

2008年11月30日20:32

カテゴリ

Economics

[中級経済学事典] 複数均衡

一時、IT業界で収穫逓増というbuzzwordが流行したが、最近は忘れられたようだ。しかし、この概念は現在の状況を考える上で役に立つ。かつて収穫逓増として騒がれたのは、経済学で正確にいうとネットワーク外部性である。これは古典的な意味での収穫逓増(規模の経済)とは違い、ある人の行動による利益が他人の行動に依存するという補完性である。数学的に表現すると、プレイヤーA、Bの行動a、bによる利得関数f(a,b)を2階微分可能とすると、

∂2f/∂a∂b≧0

これはsupermodular gameとよばれ、利得が最大と最小の二つのナッシュ均衡をもつ複数均衡になる。これを最適反応曲線で描くとコーディネーションの失敗の図になるが、利得関数で描くと次のような図になる。今アメリカ経済が落ち込んでいるのは局所最適だが、全員が協力すれば全体最適が達成可能だとしても、人々の行動の初期値がXより下であるかぎり、非協力(取り付け)がナッシュ均衡になる。他人の行動を所与とするかぎり、自分だけがそこから離れることは合理的ではないからだ。

ケインズ的な失業も、こういう非凸の最適化問題として理解できるが、これは限界原理のような漸近的な最適化手法では解けない(Cooper-John)。これはITでもおなじみの、他人がみんなウィンドウズを使っているときは、たとえマッキントッシュのほうが性能がよくても自分だけマックに変えると損をする、というネットワーク外部性と同じである。

この場合に考えられる政策は、政府がまず協力的な行動をとり、世の中が協力するという期待を作り出すことだ。このためには、政府が一時的には(たとえば巨額の不良債権を買い取るなど)大きな損失を覚悟して高い山に上り、そこから絶対に降りないというコミットメントを示す必要がある。これがアメリカで多くの経済学者が「大胆な」とか「非正統的な」といった表現を使う理由だ。普通の(合理的な)行動ではだめで、一時的には不合理なコミットメントが必要なのだ(ただし山の頂上まで行く必要はなく、期待値がXを上回ればよい)。

しかし、これは必要条件にすぎない。絶対多数の投資家が政府を信頼するためには、全体最適となるナッシュ均衡が存在するという共有知識が必要だ。そのためには金融システムが正常化し、人々が合理的に行動すれば全体最適に収束することが条件だ。いいかえると、

人々の行動の期待値がXより上になり

協力がナッシュ均衡だという期待が共有される

という二つの条件が必要である。このうち本質的なのは後者で、たとえ政府が債券や株式やケチャップを買いまくっても、財政赤字でいつまでもそんな政策が続けられないと市場が思えば、全体最適はナッシュ均衡にならないので、自律的に維持できない。逆に後者が成り立てば、世界的には資金過剰なので、市場を出し抜いて自分だけ高い山に登ろうという長期投資家(SWFなど)が出てくるだろう。つまり重要なのは、不良債権を清算して「値洗い」し、これ以上悪い均衡にとどまっていても損するという状況を作り出すことである。

これは日本でも同じで、政府が信用されない状態でいくらバラマキをやっても、市場はすぐ悪い均衡に戻ってしまう。そのバラマキの方法も二転三転するようでは、よい均衡の存在もあやしくなり、「景気対策」としても意味をなさない。遠回りのようでも、企業収益を高めて市場の信認を回復することが最善の政策である。

___

if a coincides with p england has to pay for hfr inported linen the full

http://www.palgrave.com/jp/book/9781349024797

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=-46wCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA149&dq=if+a+coincides+with+p+england+has+to+pay+for

++imported+linen+the+full+marshall&hl=ja&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiij_

HO2szYAhWCKJQKHcfLA0gQ6AEILTAC#v=onepage&q=if%20a%20coincides

%20with%20p%20england%20has%20to%20pay%20for%20%20imported%

20linen%20the%20full%20marshall&f=false

…

Early Economic Writings, 1867-90 - 149ページ

Early Economic Writings, 1867-90 - 149ページhttps://books.google.co.jp/books?isbn...

John K. Whitaker, Alfred Marshall - 1975 - プレビュー - 他の版

Alfred Marshall John K. Whitaker ... With regard to division of the benefits of the trade between the two countries it may be remarked that if A coincides with P England has to pay for her imported linen the full equivalent of what it would cost her to make it ... The further A is above P, the greater is the benefit that England derives from the trade: the further A is to the right of R, the greater is the benefit that Germany derives from the ...

Early Economic Writings, 1867-90

著者: Alfred Marshall

____

https://translate.google.co.jp/translate?hl=ja?sl=auto&tl=ja&u=http%3A//nam-students.blogspot.jp/2018/01/mill-principles-of-political-economy.html

Mill, Principles of Political Economy, Book III, Chapter XVIII | Library of Economics and Liberty

http://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/mlP47.html

The supposition was, that England could produce 10 yards of cloth with the same labour as 15 of linen, and Germany with the same labour as 20 of linen; that a trade was opened between the two countries; that England thenceforth confined her production to cloth, and Germany to linen; and, that if 10 yards of cloth should thenceforth exchange for 17 of linen, England and Germany would exactly supply each other's demand: that, for instance, if England wanted at that price 17,000 yards of linen, Germany would want exactly the 10,000 yards of cloth, which, at that price, England would be required to give for the linen. Under these suppositions it appeared, that 10 cloth for 17 linen would be, in point of fact, the international values.

III.18.37

But it is quite possible that some other rate, such as 10 cloth for 18 linen, might also fulfil the conditions of the equation of international demand. Suppose that, at this last rate, England would want more linen than at the rate of 10 for 17, but not in the ratio of the cheapness; that she would not want the 18,000 which she could now buy with 10,000 yards of cloth, but would be content with 17,500, for which she would pay (at the new rate of 10 for 18) 9722 yards of cloth. Germany, again, having to pay dearer for cloth than when it could be bought at 10 for 17, would probably reduce her consumption to an amount below 10,000 yards, perhaps to the very same number, 9722. Under these conditions the Equation of International Demand would still exist. Thus, the rate of 10 for 17, and that of 10 for 18, would equally satisfy the Equation of Demand: and many other rates of interchange might satisfy it in like manner. It is conceivable that the conditions might be equally satisfied by every numerical rate which could be supposed. There is still therefore a portion of indeterminateness in the rate at which the international values would adjust themselves; showing that the whole of the influencing circumstances cannot yet have been taken into account.

III.18.38

§7. It will be found that, to supply this deficiency, we must take into consideration not only, as we have already done, the quantities demanded in each country of the imported commodities; but also the extent of the means of supplying that demand which are set at liberty in each country by the change in the direction of its industry.

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=1Y3UP9YoYpUC&pg=PA94&dq=Multiple+equilibria+

mill+essayes&hl=ja&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjAltaFvszYAhVCjZQKHY6pApoQ6AEIJjAA

#v=onepage&q=Multiple%20equilibria%20mill%20essayes&f=false

for strong comments on the use of constant elasticities mill

mcc

john stuart mill

Centenary Essays on Alfred Marshall

John K. Whitaker

ミル、政治経済の原則、書籍III、第XVIII章| 経済と自由の図書館

http://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/mlP47.html

イギリスはリネン15本と同じ労働で10ヤードの布を、リネン20本と同じ労働をしてドイツを生み出すことができたと仮定した。 両国間で貿易が開かれたこと、 その後イギリスは彼女の生産を布に限定し、ドイツはリネンに限定した。 それから10ヤードの布がその後17本のリネンを交換すべきならば、イングランドとドイツは正確にお互いの需要を供給するでしょう。例えば、イングランドがその価格でリネン17,000ヤードを望むなら、ドイツは10000ヤードその価格で、イングランドはリネンを与える必要があります。 これらの仮定の下では、17本のリネンのための10本の布が、実際には国際的価値観になると思われました。

III.18.37

しかし、18リネンの10布などの他の料金も、国際需要の方程式の条件を満たす可能性があります。 この最後のレートでは、イングランドは17の場合の10の割合よりも多くのリネンを望むが、安い割合の割合ではないと仮定する。 彼女は1万ヤードの布で今買える18,000を望んでいないだろうが、9722ヤードの布で(18の新しいレートで10を支払う)17,500で満足するだろう。 ドイツは、17歳で10時に買うことができた時よりも布を愛していなければならないので、消費量を1万ヤード以下、おそらくは9722と同じに減らすでしょう。これらの条件の下、国際需要方程式まだ存在するだろう。 したがって、17の10の割合と18の10の割合は等式的に需要の式を満たし、他の多くの相互交換の割合は同様の方法でそれを満たすかもしれない。 想定されるあらゆる数値速度によって条件が等しく満たされることが考えられる。 したがって、依然として、国際的な価値が調整される率には不確定性の部分がある。 影響を与える状況の全体がまだ考慮されていないことを示しています。

III.18.38

§7。 この欠点を補うためには、すでに行っているように、輸入商品の各国で要求される量だけでなく、 その産業の方向性の変化によって各国の自由に設定されている需要を供給する手段の程度もまた変化する。

___

http://d.hatena.ne.jp/himaginary/20100814/history_versus_expectations

20100814

均衡を決めるのは歴史か、それとも期待か?

経済 |

Rajiv Sethiが、ンゴジ・オコンジョ・イウェアラ(Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala)世銀専務理事が「サハラ以南こそ次のBRICSだ」とぶち上げた*1講演を取っ掛かりに、表題の件について考察を巡らしている。

「History Versus Expectations in Sub-Saharan Africa」と題したそのブログエントリで彼は、クルーグマンの「History Versus Expectations」という1991年の論文から以下の文章を引用している。

Once one has multiple equilibria, however, there is an obvious question: which equilibrium actually gets established? Although few have emphasized this point, there is a broad division into two camps... On one side is the belief that the choice among multiple equilibria is essentially resolved by history: that past events set the preconditions that drive the economy to one or another steady state... On the other side, however, is the view that the keydeterminant of choice of equilibrium is expectations: that there is a decisive element of self-fulfilling prophecy...

The distinction between history and expectations as determinants of the eventual outcome is an important one. Both a world in which history matters and a world of self-fulfilling expectations are different from the standard competitive view of the world, but they are also significantly different from each other. Obviously, also, there must be cases in which both are relevant. Yet in the recent theoretical literature models have tended to be structured in such a way that either history or expectations matter, but not both... in the real world, we would expect there to be circumstances in which initial conditions determine the outcome, and others in which expectations may be decisive. But what are these circumstances?

(拙訳)

複数均衡が存在するならば、次の疑問が出てくるのは明らかだ:どの均衡が実際に達成されるのか? これについてはあまり指摘されていないが、大まかに言って見方が二つに分かれる。・・・一つの見方は、複数均衡における選択は基本的に歴史が解決する、というものだ。過去の出来事によって培われた事前条件が、経済をどちらかの定常状態に追いやる、というわけだ。・・・もう一つの見方は、均衡の選択を決定する鍵となるのは期待だ、というものだ。つまり、自己実現的予言という要素が厳然として存在する、というわけだ。・・・

歴史と期待のどちらが最終結果を決める要因なのか、という識別は、重要なものだ。歴史が重きをなす世界、自己実現的予言の世界、そのいずれも標準的な競争的世界観とは異なっているが、その二つの世界観同士も大いに異なっている。また、両者が同時に当てはまるケースが存在することも明らかであろう。しかし、最近の理論研究では、歴史と期待のどちらかしか効かず、両者が同時に効くことが無いような形でモデルが構築される傾向がある。・・・現実世界では、初期条件が結果を左右する状況がある半面、期待が結果を左右する状況もある、と我々は考える。その場合の状況とはどういったものだろうか?

この疑問を追究するためにクルーグマンは、収穫一定の財Cと収穫逓増の財Xから成る2財モデルを提示している。

そのモデルでは、Xの生産に従事する労働者が少ないと、X産業はC産業に比べて高い賃金を確保することができない。そのため人がX産業からC産業に流出し、最終的には全員がC産業で働く、という均衡に落ち着く。

一方、ある水準以上の数の労働者がX産業に集まると、X産業の賃金がC産業を上回り、それがますますX産業に人を惹き付ける、という好循環が回りだす。その場合の最終的な均衡は、全員がX産業で働く、ということになる。

閾値となるX産業の従事者数をLX*とすると、上述の複数均衡は以下の図で表される。

貯蓄=所得-消費

したがって

貯蓄=投資」

(ケインズ一般理論第6章より)

有効需要=消費+投資

| / _総需要

総| A/_ー

需| 有/ー

要| _ー|投 _消費

| _ー/ |資_ー

| _ー / 効_ー

| _ー / _ー|

| _ー /_ー |消

|ー /ー 需|

| _ー |

| _ー/ |費

|ー / 用|

| / |

|/45度_______|_______

↑ 総生産、供給(GDP)

雇用量もここで決まる

総需要=総供給を示す線は45度の傾きをもつ。一国の有効需要は点Aで均衡する。

有効需要=消費+投資は、ケインズ理論の核となる考え方のひとつ。

(中野明『図解ケインズ』)

上記図からIS-LM曲線(ヒックス考案)が導かれる…

多分、国債赤字と民間黒字も45度線でいい

| / _

民| /_ー

間| /ー

債| _ー| _

権| _ー/ | _ー

| _ー / _ー

| _ー / _ー|

| _ー /_ー |

|ー /ー |

| _ー |

| _ー/ |

|ー / |

| / |

|/45度_______|_______

政府負債

ただし複利が表現され得ない

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home