ビル・ミッチェル「ケインズに先駆けて大恐慌から日本を救った男、高橋是清」(2015年11月17日)

[Bill Michel, “Takahashi Korekiyo was before Keynes and saved Japan from the Great Depression,“ billy blog, Novenber 17, 2015] [★]

このエントリーは、以前に明示的財政ファイナンス(OMF)について書いた一連のエントリーに追加された第二部のエントリーだ。前英国金融サービス機構長官のアデア・ターナーは、2015年11月5日から6日に掛けて、ワシントンで開かれたIMF主催の第十六回ジャック・ポラック年次研究会議で新しい論文–The Case for Monetary Finance – An Essentially Political Issue–をちょうど出した。その論文では明示的財政ファイナンスが提唱されていたが、私はその内容を受け入れられない。それについては明日書くだろう (それはPart2になるが、二つの記事は必ずしもつながってないだろう)。

アメリカのジャーナリストのジョン・キャシディが、2015年11月23日発行のニューヨーカー誌でターナーについて書いている最新の記事を紹介しよう。-Printing Money。題名からわかるように、全く中央銀行の操作ニュアンスを正しく理解してない。彼はまたジンバブエやワイマール共和国のホラ話を持ち出すが、その詳細に対して単に無知なだけでなく、たとえ金融操作が関係しようとも、あらゆる支出が―公的、私的問わず―インフレリスクを抱えている事を学んでいない恐怖のネオリベラリズムのお仲間のひとりであるのがわかっている。それについては明日書くとしよう。しかしながら、今日はその背景として、私が第二次世界大戦前の日本経済政策について進めているある研究について報告しよう。これは、とても為になるし、明示的財政ファイナンスについての私たちの考えに結びついているからだ。今日の話題はそれだ。

高橋是清–は日本の第20代内閣総理大臣で、1932年に臨時な地位に就任したのを最後に総理大臣を2回務めた。彼は以前、日本銀行で働いていた。ほとんどの場合において、1920年代後半から1936年の彼の死まで、さまざまな政権の下で財務大臣だった。

私は、現在取り組んでいる本の企画の一環として、これまでかなりの期間、日本銀行の公文書を研究し続けている。高橋是清が日本の経済政策を形成する上で主要な人物であった時代まで進んで、この事はアデア・ターナーやジョン・キャシディに判断を下したいコメントとちょうど偶然にも一致している。

そこで、この背景が明日に備えて助けになるだろうと思った。

高橋是清は、1931年12月13日に金本位制を離脱、中央銀行の与信を伴った大規模な財政政策を行ない、その結果として日本を救ったことで名高い。その事で非常に高い評価を受けている。彼の行動とそれに続いた結果は、明示的財政ファイナンスが望ましいかどうかを評価する基準への確固たる証拠を与えている。

明示的財政ファイナンスは、現代金融理論(MMT)の中心となる政策であり、その点をキャシディは不安を感じているようだ。その詳細については明日。

高橋是清に関して、1936年に所謂226事件で―そのクーデターは失敗したが― (就寝中に銃撃と刀による) 反乱陸軍将校たちによって彼が暗殺された事と彼の貨幣に対する洞察が関連していたとは考えてない。

実際には、彼は軍事費を削減していた、なぜならば、日本の軍国主義を弱めるのを望んでいた穏健主義者だったからだ。その為に敵対者たちを作った。彼らは武器を所持しており、その使い方を知っていた!

これの背景として、日本は1927年に大手民間銀行の経営破綻を経験した (昭和金融恐慌)。その結果として”戦後の破綻まで遡る、過去の欠陥に対して度重なる失敗の隠蔽とその場しのぎの手段”として見なされている。(高橋亀吉『大正昭和財界変動史』第二巻、東洋経済新報社、東京、P.739から引用)

言い換えるのなら、1920年代に日本に於いて、バンクスター(訳者注:顧客をだまして利益を挙げる強欲な銀行幹部)たちは退出させられた。高橋亀吉は、1920年代後半の昭和金融恐慌を機に生じた改革は高橋是清が導入した刺激策の補助になったと論じている。

高橋是清によって行なわれた重要な刺激策が三つあった:

1. 日本が1931年12月に金本位制を離脱した後に、為替レートは対米ドルで60%、対英ポンドで44%下落した。為替の下落は、1931年12月から1932年11月の間で起こった。それから日本銀行は1933年4月以降には平価を安定させた。

2. 彼は拡張的財政刺激策を導入した。1932年3月、高橋は日本銀行が政府国債(即ち、政府支出を促進するために関連銀行口座に入金して)を引き受ける政策を提案した。

この提案は、1932年6月18日に国会で可決された。国会では向こう12カ月の財政政策戦略を可決したが、それは100%日本銀行の信用によって賄われる財政赤字を伴うものだった。

日本銀行の歴史家の鎮目雅人は日本銀行レビュ-(2009年4月)にて論じていた。–両大戦間期の日本における恐慌と政策対応:金融システム問題と世界恐慌への対応を中心に – これによると

財政政策については、日本は1930年代の高橋財政期を通じて、他国に比べて大幅な財政赤字を継続していた。

1932年12月25日に、日本銀行は政府支出の“引受”を始めた。

3. 日本銀行は、1932年(3月,6月,8月)と数回、再び1933年初頭に金利を引き下げた。利下げはイングランド銀行とアメリカのFRBの利下げに追随したものだった。従って、金融政策の利下げは各国とも共通していたが、財政政策による刺激の大きさは日本独自のものだった。

鎮目雅人は次のように論じている:

高橋財政のマクロ経済的側面に着目する多くの論者は、ケインジアン政策の先駆的な成功例として、高橋財政に積極的な評価を与えてきた。例えば、キンドルバーガーは、高橋是清が典型的なケインズ政策を行ったと指摘しており、以下のように述べている。「彼の著述は、彼が1931 年『エコノミック・ジャーナル』誌のR・F・カーンの論文に当ったような徴候は何もないのに、ケインズ的な乗数機構をすでに理解していたことを示した」

[完全な出典は:鎮目雅人(2009)“両大戦間期の日本における恐慌と政策対応:金融システム問題と世界恐慌への対応を中心に “ 日銀レビュー,2009-E-2]

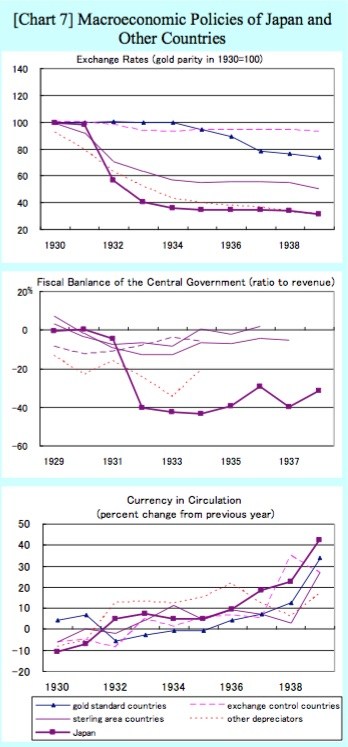

次のグラフは、鎮目雅人の論文から日本と他国のマクロ経済政策を比較した図表7を転載したものである。これを見れば一目瞭然だ。

他の通貨ブロック圏と日本との間の大きな違いは、財政政策にある。

これらの三つの異なる刺激策の相対的な影響については、この論文の中では相当の議論があるが、次の事は明らかだ:

1. 実質GDP成長率は急速に回復し、景気後退に陥った他国と比較して際立っていた。1932年から1936年の間に、実質鉱工業生産は62%と驚異的に増大した。

2. また大恐慌の初期において急落していた雇用は、高橋介入の後では力強く成長した。

3. インフレは、1933年の為替の下落の結果として急上昇したが、財政と金融刺激の下支えによって経済成長率が上がったので急速に低水準となり、1934年には安定した状態となった。

金本位制の放棄は、政府に大規模な国内刺激策を導入する余地を与えたので、これが決定的な最初の一歩になったのは明らかだ。金本位制下に於いては、これらの政策は対外赤字を押し出して金保有量の流出を招くので不可能だった。

私は、アメリカの共和党現職大統領候補の多くが、再び金本位制への復帰を訴えかけているのに注目している。各国がこのような為替レートの仕組みを採用した時の最悪の記憶を考えれば、彼らは明らかに何を語っているのかを理解してないだろう。

大恐慌を確固たるものにしたのは、金本位制である事は確かだ。 (景気後退によって輸入が停止した後の)1929年に、アメリカが貿易黒字を計上し始めたのに連れて、他の国々は資本流入を促すために金利を引き上げなければならないので金保有量が枯渇し始めた。アメリカの景気後退は広がっており、ヨーロッパの多くの投資家は、他の中央銀行が平価切下げを行わなければならないだろうと考えた。このように予測したので、投資家たちは金を引き出し、マネーサプライが減少して景気は悪化した。それから銀行たちは破綻した。

グレッグ・イップに寄るおもしろい記事(2015年11月12日)がある。- What Republicans Get Wrong About the Gold Standard -この話題に関係しており、愚かな共和党候補者たちを標的にしている。

疑いもなく、高橋是清は、金本位制下では各国はその金保有量と比例したマネーサプライを維持しなければならず、それが国内政策において制約を課しているのを理解していた。彼はその制約を除去することで、その次には(日本銀行を通した)財政と金融手段を使って国内需要を狙い撃ちできた。

一部の研究者たちは、為替レートの下落と財政刺激の提携が“活動レベルに重大な影響を及ぼしていた”事を示唆している。(Nanto, D.K. and Takagi, S. (1985) ‘Korekiyo Takahashi and Japanese Recovery from the Great Depression’, American Economic Review, 75, 369-74を参照).

それらの研究のほとんどが示唆するのは、金融緩和政策(金利の引き下げ)が他の二つの刺激策ほど重要ではなかった事だ。

もう一つの議論の立脚点は、1930年代初頭の民主主義からファシズムの過渡期に於いて、労働組合は抑圧されて労働争議は減少した。その結果として、実質賃金は低下し雇用と産出の回復を齎したという主張もある。

2000年9月30日に、韓国の学者Myung Soo Chaによる興味深い論文が発表された。– – Did Korekiyo Takahashi Rescue Japan from the Great Depression?

大恐慌期間中での、その特異な回復への影響を調べるために、これらの刺激策と賃金下落とで因数を分離して求めた。また、この回復が日本の外部の出来事によって起こったものかどうかを調べるために、(日本の輸出への)世界的な産出の影響も含めている。

統計的手法 (ベクトル自己回帰分析) と日本銀行が公開している歴史的データを使って、大恐慌初期での日本では”下降を反転させる上で決定打だった“のは財政主導であった事を論証している。

余談として、日本銀行は素晴らしい歴史的統計ページを運営している。この時期を研究するのに他の有益なソースがある。-例えば、the League of Nations, International Statistical Yearbook -これはアメリカのノースウェスト大学を通してオンラインで利用できる。

次のグラフはMyung Soo Chaの図1をコピーしたもので、1920年代中盤から1937年にかけての工業生産の発展を示している。

日本の体験は、当時の他の主な経済国と完全に異なっており、特に高橋是清によって導入された一連の大規模な刺激策の後ではそれは明らかだ。

また、興味深い事に各国のグラフ上での転換点が、“景気後退後に金本位制を離脱した順番と一致している事だ。:イギリス、ドイツ、日本は1931年に、アメリカは1933年、最後にフランスが1936年” これは偶然ではない。

彼の方法論にこれ以上は言及しないだろう。(それは標準的なものだ) この種の計量経済分析に興味があるのならば、あなた自身でその論文を読んでみるといい。

彼の研究結果は、非常に明瞭だ。

1. 彼は、“日本において大恐慌を終わらせるのに、高橋の財政拡大の卓越した役割について感銘を受けずにはいられない。” と綴っている。

2. “特に高橋是清が行なった赤字支出は、不況を素早く終わらせるのに極めて重要だったのがわかっている”

3. “平価切下げは、1932年に於いては救済になったが、生産量の伸びへの貢献はささやかなものだった”

4. “円安は同様に刺激を与えたが、日本国外部からのインフレ収縮を上回るほど十分には強くなかった”

鎮目雅人の研究からもう一つわかった事は、自由民主主義からファシズムの過渡期において、インフレ期待が幾分か上昇したことだ。 “デフレーションからインフレーションへの期待の変化は、主に通貨下落の結果であり日本銀行の国債引受ではない”

財政刺激を提供したのは軍事費の増大であり、現在に於いては好ましいものではなかったと主張する人々がいるかもしれない。

しかし、研究が示唆するのは、刺激に対する財政転換のうち軍事費の割合は公平に見て取るに足りないものだった。

(例えば、Metzler, M. (2006) Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan, Berkeley, University of California Press).

結論

高橋是清の経済政策姿勢は-その作用はとても現代金融理論(MMT)的だ-日本を大恐慌から救った。

主に中央銀行の与信引受を伴う大規模な財政刺激は、インフレ率の暴騰を引き起こさなかったし、インフレーションを加速しなかった。

インフレーションは、短期間で上がり、それから再び落ちたが、これは主に大幅な平価切下げの結果に寄るものだ。これは、常に日本のような小国開放経済(当時は-小国である)で起きるかもしれない結果である。

不必要な側面-例えば軍事費など-はあったが、高橋是清の‘実験’は現代に於いて、明示的財政ファインンスを議論するのに関連があるのは明らかだ。

私は、最新の著作-Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale(2015年5月発行)-の中で、明示的財政ファイナンスがユーロ圏(それ自身から)を救う可能性があると論じている。

ブリュッセルとフランクフルトの政策立案者に於いては、1931年に高橋是清が実行したような深い政策的な洞察と展望の提示をしてみよう。

パブでの政治-ハミルトンー2015年11月17日

今夜、私は(ニューキャッスル郊外、NSWの)バーモント通りにあるハミルトンステーションホテルで開催されるパブでの政治において講演するつもりだ。

講演タイトルは’なぜオーストラリアにとって財政赤字は好ましいのか’であり、2013年4月29日のニューヨークタイムズ紙で、アメリカの哲学者ダニエル・デネットが語った事から引用して講演するつもりだ:

人々に対して、『彼らは幻想に人生を捧げている』と礼儀正しく告げる方法は単に存在しない…

私たちはそれを楽しむつもりだ!

イベントは18:30に始まる。

地元の読者はそこで見物して欲しい。

今日はここまで!

Takahashi Korekiyo was before Keynes and saved Japan from the Great Depression

This blog is really a two-part blog which is a follow up on previous blogs I have written about Overt Monetary Financing (OMF). The former head of the British Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner has just released a new paper – The Case for Monetary Finance – An Essentially Political Issue – which he presented at the 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, hosted by the IMF in Washington on November 5-6, 2015. The paper advocated OMF but in a form that I find unacceptable. I will write about that tomorrow (which will be Part 2, although the two parts are not necessarily linked). I note that the American journalist John Cassidy writes about Turner in his latest New Yorker article (November 23, 2015 issue) – Printing Money. Just the title tells you he doesn’t appreciate the nuances of central bank operations. He also invokes the Zimbabwe-Weimar Republic hoax, which tells you that he isn’t just ignorant of the details but also part of the neo-liberal scare squad that haven’t learnt that all spending carries an inflation risk – public or private – no matter what monetary operations migh be associated with it. I will talk about that tomorrow. Today, though, as background, I will report some research I have been doing on Japanese economic policy in the period before the Second World War. It is quite instructive and bears on how we think about OMF. That is the topic for today.

Takahashi Korekiyo – was the 20th Prime Minister of Japan and held office twice the last time in an acting capacity in 1932. He had previously worked in the Bank of Japan. For the most part though, he was Finance Minister under various administrations from the late 1920s until his death in 1936.

I have been researching documents in the Bank of Japan archives for some time now as part of a book project I am working on. I am up to the period that Takahashi Korekiyo was a major player in Japanese economic policy making and it just happens to fit in with the comments I wish to make about Adair Turner and John Cassidy.

But I thought this background would help us for tomorrow.

Takahashi Korekiyo is famous for abandoning the Gold Standard on December 13, 1931 and introducing a major fiscal stimulus with central bank credit which rescued Japan from the Great Depression in the 1930s. That is quite a reputation. His actions and the subsquent results provide a solid evidence base for assessing whether OMF is desirable.

I note that OMF is core Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) policy, a point that Cassidy seems to be worried about. More about that tomorrow.

As to Takahashi Korekiyo, I don’t think his monetary acumen had anything to do with his assassination (in his sleep by gunshot and sword) by rebel army officers in 1936 during the so-called – February 26 Incident – which was a failed coup d’état.

He had in fact reduced military funding because he was a moderate and wished to reduce Japan’s martial tendencies. Enemies were thus made and they were the type of enemies that carried weapons and knew how to use them!

As background, Japan had experienced a major private banking collapse in 1927 (the Showa Financial Crisis) as a result of what has been referred to as “cumulative mismanagement of cover-ups and halfway measures against earlier flaws dating back to the post-war collapse” (quote from Takahashi, Kamekichi [1955a], Taisho Showa Zaikai Hendou Shi (A History of Economic Fluctuations during Taisho and Showa Eras), vol.2, Toyo Keizai Shinposha, Tokyo, p.739).

In other words, the banksters were out in force in Japan during the 1920s. It is argued by Takahashi Kamekichi that the stimulus measures introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo were assisted by the reforms that were made in the late 1920s to deal with the Showa Financial Crisis.

There were three notable sources of stimulus introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo:

1. The exchange rate was devalued by 60 per cent against the US dollar and 44 per cent against the British pound after Japan came off the Gold Standard in December 1931. The devaluation occurred between December 1931 and November 1932. The Bank of Japan then stabilised the parity after April 1933.

2. He introduced an enlarged fiscal stimulus. In March 1932, Takahashi suggested a policy where the Bank of Japan would underwrite the government bonds (that is, credit relevant bank accounts to facilitate government spending).

This proposal was passed by the Diet on June 18, 1932. The Diet passed the government’s fiscal policy strategy for the next 12 months with a rising fiscal deficit 100 per cent funded by credit from the Bank of Japan.

Bank of Japan historian Masato Shizume wrote in his Bank of Japan Review article (May 2009) – The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Ipact of the World Depression – that:

Japan recorded much larger fiscal deficits than the other countries throughout Takahashi’s term as Finance Minister in the 1930s.

On November 25, 1932, the Bank of Japan started ‘underwriting’ the government’s spending.

3. The Bank of Japan eased interest rates several times in 1932 (March, June and August) and again in early 1933. This easing followed the cuts by the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank in the US. Monetary policy cuts were thus common to each but the size of the fiscal policy stimulus was unique to Japan.

Masato Shizume wrote that:

[The full reference is: Shizume, Masato (2009) “The Japanese Economy during the Interwar Period: Instability in the Financial System and the Impact of the World Depression”, Bank of Japan Review, 2009-E-2]A number of observers who focus on the macroeconomic aspects of the Takahashi economic policy praise Takahashi’s achievements as a successful pioneer of Keynesian economics. Kindleberger points out that Takahashi conducted quintessential Keynesian policies, stating, “his writing of the period showed that he already understood the mechanism of the Keynesian multiplier, without any indication of contact with the R. F. Kahn 1931 Economic Journal article.”

The next graph is a reproduction of Chart 7 Macroeconomic Policies of Japan and Other Countries from Masato Shizume’s paper. It is self-explanatory.

The big variation between the different currency blocs and Japan is in fiscal policy.

There is substantial discussion in the literature about the relative impacts of these three different stimulus measures. But what followed is clear:

1. Real GDP growth returned quickly and stood out by comparison with the rest of the world which was mired in recession. Between 1932 and 1936, real industrial production grew by a staggering 62 per cent.

2. Employment, which had also plummeted in the early days of the Great Depression, grew robustly after the Takahashi intervention.

3. Inflation spiked as a result of the exchange rate depreciation in 1933 but quickly fell to low and relatively stable levels in 1934 as the economy’s growth rate picked up under the support of the fiscal and monetary stimulus.

It was clear that abandoning the Gold Standard was a crucial first step because it gave the government space to introduce major domestic stimulus policies. These policies were not possible under the Gold Standard because they would have pushed out the external deficit and the nation would have lost its gold stocks.

I note a number of the current Republican presidential potentials in the US are once again calling for a return to the Gold Standard. They clearly haven’t a clue what they are talking about given the appalling record of nations when they were on such exchange rate mechanisms.

It was the Gold Standard that ensured the Great Depression ensued. As the US started to run trade surpluses in 1929 (after the recession choked off imports), other nations started to deplete their gold stocks which meant they had to raise interest rates to attract capital inflow. The US recession spread and many investors in Europe considered that the central banks would have to devalue. Anticipating that, they withdrew gold and the contractionary effects on the money supply worsened the downturn. Then banks collapsed and so on.

There is an interesting article (November 12, 2015) by Greg Ip – What Republicans Get Wrong About the Gold Standard – that bears on this issue. It is targetted at those stupid Republican candidates.

Clearly, Takahashi Korekiyo understood the constraints that the Gold Standard and the need to maintain the money supply in proportion with the nation’s stock of gold imposed on domestic policy. Once he removed that constraint he could then use the fiscal and monetary tools available to him (and through the Bank of Japan) to target domestic demand.

Some researchers have suggested that the combination of the exchange rate depreciation and the fiscal stimulus “had significant impacts upon the level of activity” (see Nanto, D.K. and Takagi, S. (1985) ‘Korekiyo Takahashi and Japanese Recovery from the Great Depression’, American Economic Review, 75, 369-74).

Most of the studies suggest that the monetary policy easing (cutting interest rates) was not as significant as the other two stimulus measures.

Another strand of argument is that in the transition from democracy to fascism in the early 1930s, the trade unions were suppressed and industrial disputation fell. Real wages fell as a result, which some claim caused employment and output to rise.

An interesting paper was published on September 30, 2000 by the Korean scholar Myung Soo Cha – Did Korekiyo Takahashi Rescue Japan from the Great Depression?.

It sought to decompose these stimulus factors and wage reductions to see order their impact on the exceptional recovery during the Great Depression. He also includes world output impacts (on Japanese exports) to see whether the recovery was driven by events outside of Japan.

He uses statistical techniques (Vector Autoregression) and historical data released by the Bank of Japan to show that it was the fiscal initiative that “was critical in reversing the downswing” in Japan in the early years of the Great Depression.

As an aside, the Bank of Japan runs an excellent Historical Statistics page. There are other sources of data that is of use in studying this period – for example the League of Nations, International Statistical Yearbook – which is available on-line through Northwestern University in the US.

The next graph is a reproduction of Myung Soo Cha’s Figure 1 and show the evolution of Industrial Production from the mid-1920s to 1937.

It is clear that Japan’s experience was quite different to the other major economies of the day, especially after the major stimulus package introduced by Takahashi Korekiyo.

It is also interesting that the turning points in the graph for the respective countries “matches the sequence of going off gold in the wake of the Depression: Britain, Germany and Japan in 1931, the U.S. in 1933, and finally France in 1936”. That is not coincidental.

I won’t go into his methodology (it is standard) and you can read the paper yourself if you are interested in this sort of econometric analysis.

The results of his study are fairly clear:

1. He writes “one cannot but be impressed by the prominent role of Takahashi’s fiscal expansion in ending the Great Depression in Japan”.

2. “In particular, his deficit spending was found to have been crucial in ending the depression quickly”.

3. “Devaluation did help during 1932, but its contribution to output growth was modest.”

4. “The depreciating yen provided some stimuli as well, but they were not sufficiently strong to outweigh the contractionary influences from the rest of the world.”

Another finding from Shizume Mazato’s work is that while inflationary expectations rose somewhat during the shift from liberal democracy to fascism, “the shift in expectation from deflation to inflation was chiefly the result of the currency depreciation, not the BOJ underwriting of government bonds”.

Some might argue that it was the increased military spending that provided the fiscal stimulus, which would be undesirable in today’s world.

But research suggests that the military part of the fiscal shift to stimulus was fairly insignificant (see for example, Metzler, M. (2006) Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan, Berkeley, University of California Press).

Conclusion

There is little doubt that Takahashi Korekiyo’s economic policy stance – which was very MMT in operation – saved Japan from the Great Depression.

The large fiscal stimulus that was mostly underwritten with central bank credit did not cause interest rates to sky-rocket nor inflation to accelerate.

Inflation rose for a time then fell again but this was mainly the result of the massive exchange rate depreciation. That is a result that would always occur in a small open-economy such as Japan (at the time – small that is).

While there were aspects that were unnecessary – for example, the military spending – it is clear that Takahashi Korekiyo’s ‘experiment’ has relevance for us today in discussions concerning Overt Monetary Financing.

I have argued in my current book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – that OMF could save the Eurozone (from itself).

But try to get the policy makers in Brussels and Frankfurt to display as much policy acumen and foresight as Takahashi Korekiyo did in 1931.

Politics in the Pub – Hamilton – November 17, 2015

Tonight, I will be the speaker at the Politics in the Pub, which is held at the Hamilton Station Hotel, Beaumont Street, Hamilton (a suburb of Newcastle, NSW).

The title of my talk will be ‘Why budget deficits are good for Australia’ and I will motivate the talk with the quote from US philospher Daniel Dennett who told the New York Times on April 29, 2013 that:

There’s simply no polite way to tell people they’ve dedicated their lives to an illusion …

We will have some fun with that!

The event starts at 18:30.

I hope to see local readers there.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home