Functional Finance and the Debt Ratio—Part IV

This five part series will explore at length (warning!) and in detail (another warning—wonk alert!) the MMT perspective on the debt ratio and fiscal sustainability. While the approach suggests a macroeconomic policy mix and strategies for both fiscal and monetary policies that most neoclassical economists currently believe are unsustainable, ultimately the MMT preference for a significant role for fiscal policy in macroeconomic stabilization is shown to be consistent with traditional neoclassical views on fiscal sustainability.

This fourth part integrates the content of the first three parts with the functional finance strategy for fiscal policy. Warning again—this part is the longest and most detailed of the four.Functional Finance and Fiscal Sustainability

We reach the point now where we can integrate the concept of fiscal sustainability—i.e., convergence or at least bounded growth of debt service—with functional finance. In order to do that, though, we first need a brief digression on the concept of Ricardian fiscal policy (see Pavlina Tcherneva’s paper for more on the MMT view of this). The New Consensus view that came to dominate neoclassical economics in the 2000s argued for a macroeconomic policy mix in which monetary policy managed the economy and targeted inflation through a Taylor Rule-like strategy for adjusting the interest rate and fiscal policy largely got out the way by simply adhering to its intertemporal budget constraint by setting current and future taxes and spending such that the debt ratio does not rise without bound (a bit more on the policy mix here). Fiscal policy that achieves this is called Ricardian by neoclassicals. A Ricardian fiscal policy does not interfere with the central bank’s management of the macroeconomy—in most cases it preferably passive and responds endogenously to its intertemporal budget constraint only.

On the other hand, when fiscal policy is set exogenously to run permanent surpluses inconsistent with keeping the debt ratio from rising without bound, this is called non-Ricardian fiscal policy. This obviously does interfere with the central bank’s attempts to manage the macroeconomy. This is because raising the interest rate to slow inflation in the non-Ricardian scenario results in more aggregate demand through government debt service, or the government “printing money” to avoid defaulting, and thus more inflation.

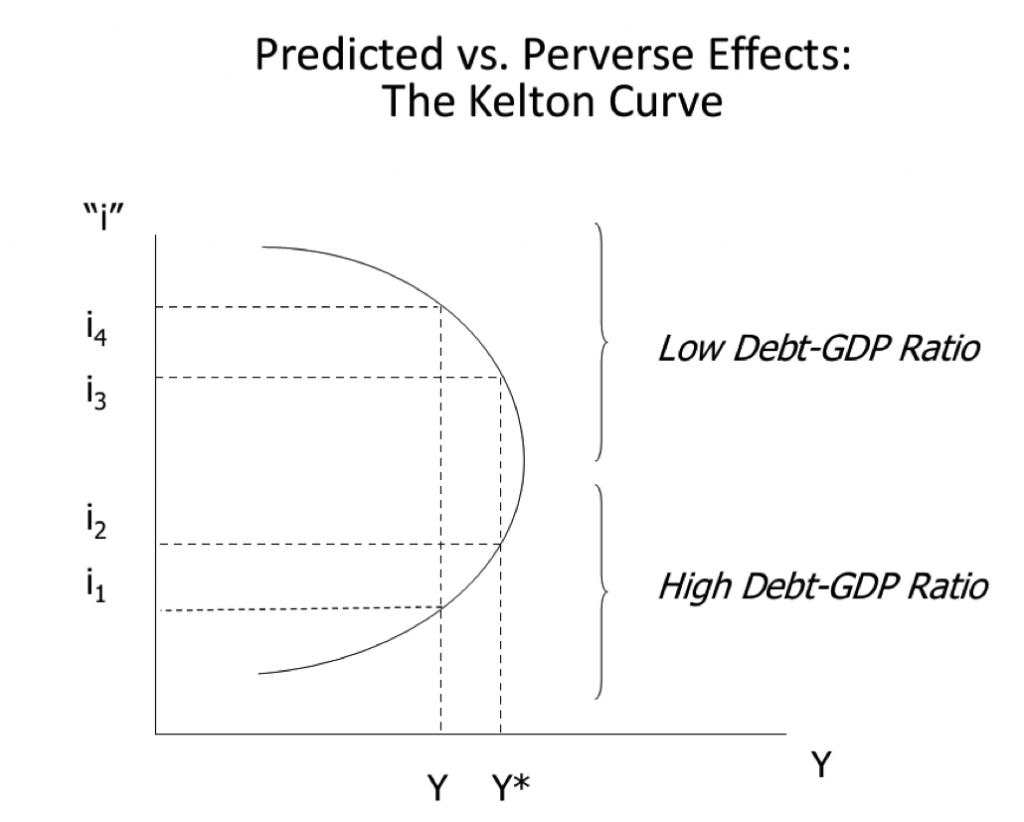

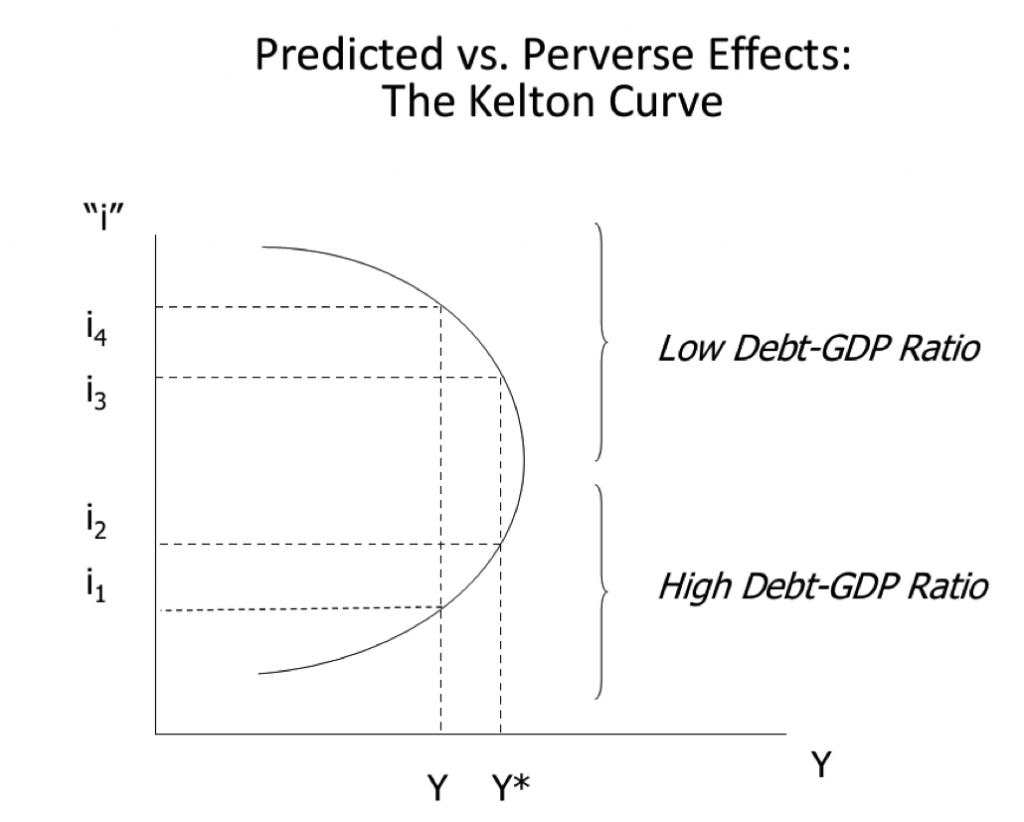

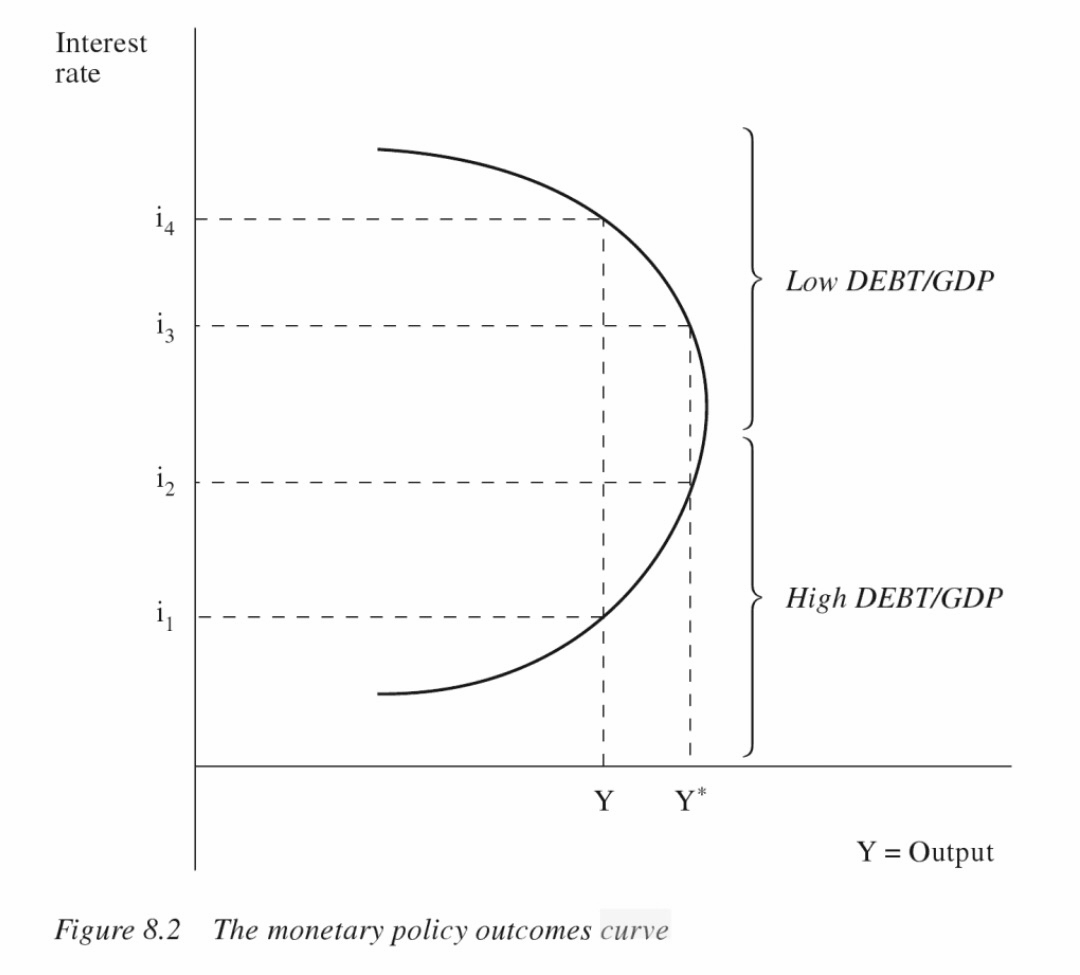

While this understanding of the monetary/fiscal policy mix is recognized in literature on fiscal sustainability, it’s puzzling how often this is neglected in more standard neoclassical analysis of macroeconomic policy effects. Indeed, most any neoclassical analysis of monetary policy shows suggests that interest rates and spending are always negatively related. As explained in 2005 by Stephanie Kelton and Rex Ballinger, often forgotten is the fact that interest payments to the non-government sector are always private sector income, and thus analysis should always incorporate it as such and not save it for special circumstances. Kelton and Ballinger present what we’ve come to call “The Kelton Curve,” (Figure 6) which shows how the relationship between interest rates and aggregate demand can be “perverse” compared to the more traditional view if rising interest rates raise spending and GDP (as in the move from i1 to i2 that raises Y to Y* in the “High Debt-GDP Ratio scenario).

Figure 6

Note that the Kelton Curve isn’t just about rising rates—it works in reverse (i.e., a move from i2to i1), which is happening right now with record low rates exacerbated by QE operations that reduce the term structure of interest rates by replacing longer-term Treasuries with overnight reserve balances. As Randy Wray explained a few months ago, the negative income effect of low interest rates has been significant in offsetting any fiscal stimulus:

But there’s a darker side. The low deposit rates and the high fees are wiping out savers. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know. You cannot even get half a percentage point on your savings at banks. Sure, your mortgage rate has also fallen, but the net effect has drained consumer’s income. Here’s a quote from a Credit Suisse report:The side-effect of the Fed’s near-zero interest medicine – the collapse in personal interest income over the last few years. The decline in interest income actually dwarfs estimates of debt service savings. Exhibit 2 compares the evolution of household debt service costs and personal interest income. Both aggregates peaked around $1.4 trillion at roughly the same time – the middle of 2008. According to our analysis of Federal Reserve figures, total debt service – which includes mortgage and consumer servicing costs – is down $206bn from the peak. The contraction in interest income amounts to roughly $407bn from its peak, more than double the windfall from lower debt service.Let’s put that in perspective. Remember the Obama fiscal stimulus? About $400 billion a year for two years—let’s say almost 3% of GDP. There’s been a big debate about whether it “worked”. Only the truly crazy believe it did not save us from an even worse recession than what we actually went through.Well, QE is removing an amount of aggregate demand from the economy equal to half of the Obama stimulus. And that is not just for two years—it goes on and on and on, year after year after year, as long as the Fed pursues ZIRP.So QE is supposed to stimulate the economy by taking 1.5% of GDP away every year?Just as we learned in the case of Japan—which experimented with ZIRP over the past two decades—extremely low rates take more demand out of the economy than they put in. So the Fed has mistaken the brake for the gas pedal: QE slams on the brakes but the Fed thinks it is sending more gas to the economy. The only thing we can be thankful for is that the Fed is driving a rickshaw, not a Buick. The damage it can do is not lethal.Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against ZIRP—I’d have ZIRP all the time—but we need to understand that it does not stimulate the economy.

And we just found out last week that QE completely removed again almost $90 billion of income from the private sector in 2012.

Contrary to neoclassicals that believe there is some rate of interest that will always bring macroeconomic stabilization, MMTers and others (like Horizontalists) think things are much more complex as there are multiple interest rates (which rate(s) should be negative? the New Consensus model has only 1 rate in it), unclear relations between them all (QE3 and its effects on mortgage rates is just one example of the uncertainties), and ultimately multiple, offsetting transmission mechanisms that must be considered (two more are that short-term rates are a cost of production via working capital finance and are perversely related to housing prices as measured by the CPI). In short, a Taylor Rule strategy grossly oversimplifies the real-world context of monetary policy and its applicability has always been seen by MMTers as highly questionable even as there is obviously some truth to the notion that some spending is negatively related to changes in interest rates.

In a world in which the Taylor Rule is a gross oversimplification, a macroeconomic policy mix based solely on monetary policy while fiscal policy makers passively balance the budget intertemporally is also overly simplistic and even destructive. From our perspective, fiscal policy should instead follow a functional finance strategy (see here and here for more) in which it is the outcomes of the fiscal policy stance in terms of unemployment, productivity (living standards), and inflation that matter, not the size of the debt ratio, per se. An appropriately designed functional finance strategy would incorporate both strong automatic stabilizers as well as a “tool kit” of options for dealing with condition in which larger stimulus or restraint are necessary.

By necessity, those details are beyond the scope here—though note that a Taylor Rule is actually just as lacking in detail, if not more so; contrary to the elevated position it has been given by neoclassicals, like functional finance, it is simply a set of principles or criteria to guide policymakers in making real-world strategic decisions based on a particular perspective of how the world works (e.g., raise interest rates when inflation rises or the GDP gap falls, and vice versa; raise interest rates more than the anticipated increase in inflation).

For functional finance, the perspective is that (a) a currency issuing government under flexible exchange rates is not constrained by the more traditional rules of “sound finance” and (b) interest on the national debt is a monetary policy variable, not a rate set by “market forces” or bond vigilantes. As such, in the context of a high debt ratio—and let’s assume the US is a high-debt ratio nation at least for the sake of argument—there are different approaches one can consider. Here are two of them, though these are not mutually exclusive, in fact:

First, Godley and Lavoie design a functional finance fiscal policy “rule” that raises spending when GDP is below potential and cuts it when GDP is above it and also adjusts government spending for the difference between actual and targeted inflation. They show that any rate of interest in this case is consistent with a stable debt ratio and this functional finance “rule.” The key is to recognize that the functional finance rule will always reduce spending whenever the deficit would otherwise be too large for potential GDP or the inflation target to be achieved and that this rule also coincidentally generates a stable debt ratio. If interest rates are high and debt service is rising, as potential GDP comes within site other government spending will fall according to the rule, stabilizing both GDP and for the context here stabilizing the primary deficit at whatever level is consistent with a stable debt ratio. If interest rates are low, the rule enables other spending to rise until potential GDP is reached, but no further. In other words, setting the functional finance strategy as a simple rule like a fiscal policy version of a Taylor rule illustrates that a true functional finance fiscal policy strategy is always Ricardian.

Godley and Lavoie then note that an effective functional finance rule—by carrying out the task of macroeconomic stabilization by itself—would enable monetary policy to focus on the distribution effects of monetary policy. They cite others that have proposed the “fair” rate of interest target, which is the growth rate of productivity plus inflation, that would enable rentiers to earn the same as wage earners (at least in theory). For our purposes here, note how a negative rate of interest—as many neoclassicals suggest is appropriate now—affects distribution; beyond the offsetting effects to fiscal stimulus reported by Wray, the distribution between savers and debtors in the private sector could make a negative nominal rate of interest deflationary, since while neoclassicals believe that negative returns lead savers to spend, in fact most retirees just receive less income in that case on their Treasuries, time deposits, and so forth, and then spend less as a result.

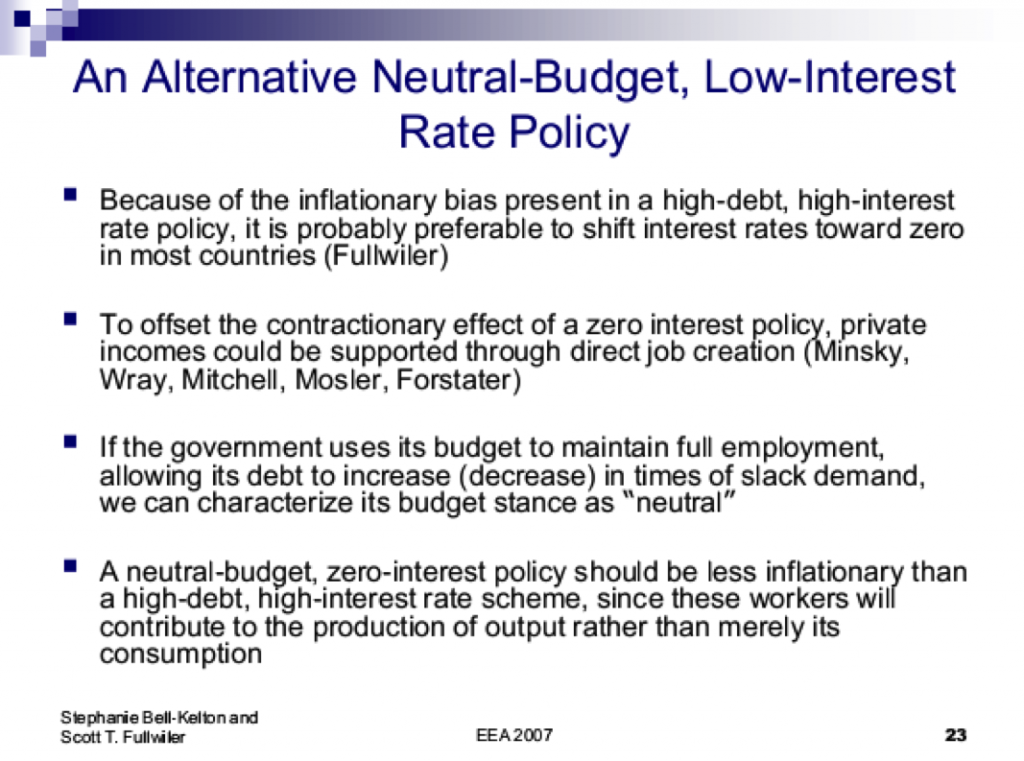

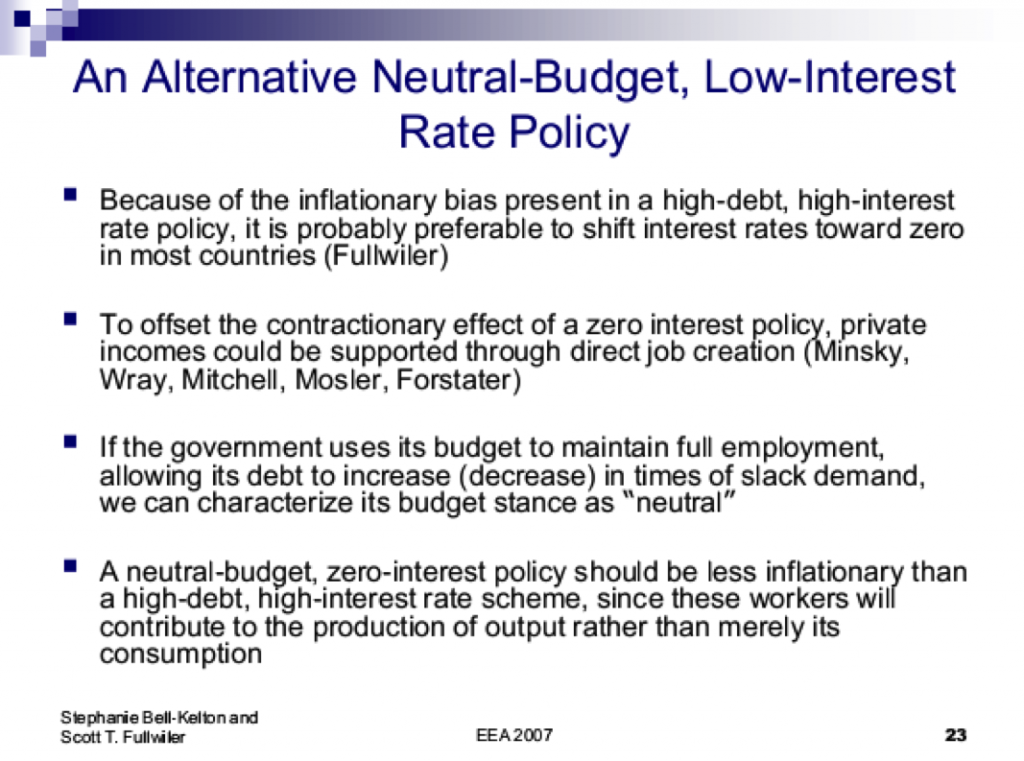

A second view—again, not necessarily mutually exclusive from Godley/Lavoie—is a more purely MMT-inspired one Stephanie Kelton and I presented in 2007, in which a permanently low short-term rate of interest is coupled with a functional finance strategy. The low rate of interest ensures debt service does not rise without bound regardless of the debt ratio or deficit, while the functional finance strategy (as it does in Godley/Lavoie) will offset whatever mix of inflationary or deflationary effects of the low short-term interest rate ultimately prevails (and for retirees, lower portfolio returns—which may or may not occur—there are ways to augment that through fiscal policy, such as Warren Mosler’s recent proposal). Consistent with the Godley/Lavoie rule, we referred to a true functional finance strategy as a “neutral” budget stance, as one could easily extend it to Godley/Lavoie’s functional finance rule to show that there would be a “neutral” functional finance budget stance for any rate of interest on the national debt and thus any debt ratio. A lower interest rate, as we propose here, might be consistent with a political climate in which it might be less politically feasible to reduce a primary deficit quickly in the face of rising debt service. And in that case, a functional finance proponent would refer to unsustainable monetary policy, not unsustainable fiscal policy, since it is far easier to simply reduce the targeted interest rate than to require fiscal action to counter monetary policy in a high debt ratio environment.

Figure 7

(The preference for a low interest rate rather than a “fair” one as they’ve defined it is a technical point that I must leave out here, though I will say that in my discussions with some Horizontalists that favor the latter the two rules aren’t necessarily contradictory since the “fair” rate is not necessarily an overnight rate (it could be a longer-term rate) whereas the MMT proposal does refer to the overnight rate.)

Another reason why the Taylor Rule for monetary policy and balanced intertemporal budget for fiscal policy mix of neoclassicals is problematic is the sector financial balances and stock-flow consistency across sectors of the economy. Anyone reading MMT literature already knows the accounting identity private sector surplus or net saving = government deficit + current account balance.

To briefly summarize, the key point is that absent a current account surplus or government deficit, the domestic private sector cannot net save, which it generally tries to do, at least on average. Thankfully, a currency-issuing government under flexible exchange rates can accommodate this desire by running a budget deficit even if there is no current account surplus, and it can run an even larger deficit if there is a current account deficit to enable the private sector to net save. Not to be confused with saving or private sector investment spending (though many do this, unfortunately), net saving is simply an indicator of how much spending the entire sector is doing relative to the sector’s income; falling net saving tends to be a signal of a move away from Minskyan hedge financing, and vice versa.

An important distinction between monetary and fiscal policy that is often unrecognized is that monetary stimulus “works” through a reduction in private sector net saving whereas fiscal stimulus works through an increase in private sector net saving (see more on this here). That is, cutting interest rates via a Taylor Rule strategy to simulate the economy can only “work” if it results in, for instance, increased business capital spending or increased household spending in both cases relative to income. This ultimately raises tax revenues to the federal government, thereby improving the government’s budget balance and reducing the private sector’s net saving (note—again, just as a technical aside—that private sector saving overall increases with the business capital spending—by accounting definition—but private sector net saving has fallen). For fiscal policy, there is a transfer of income or a tax cut that raises private sector income first—subsequent spending as a result will result in additional tax revenues that somewhat offset the initial increase in net saving for the private sector, but the overall effect is an increase aside from cases of extremely large multiplier effects (which probably only happen in theory).

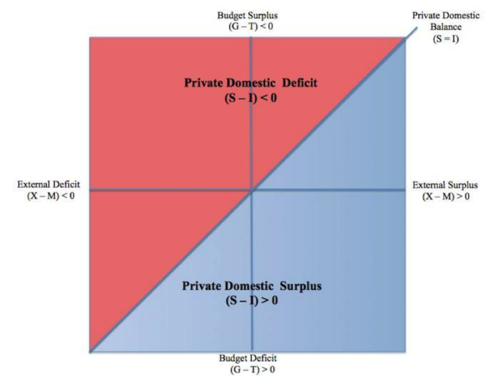

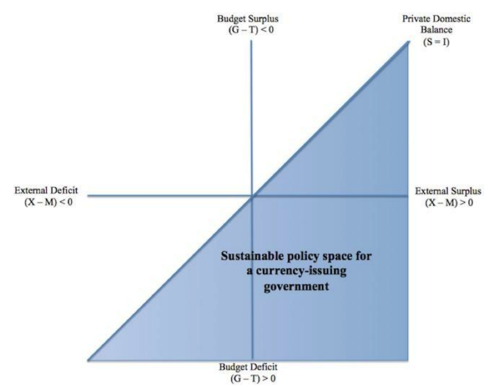

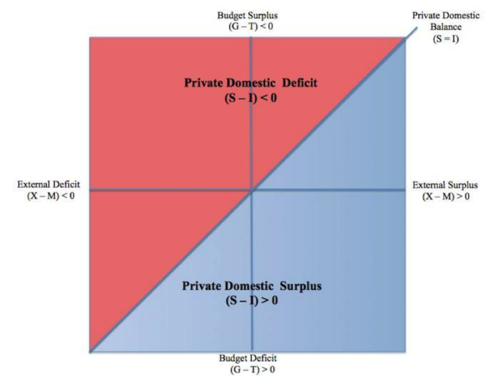

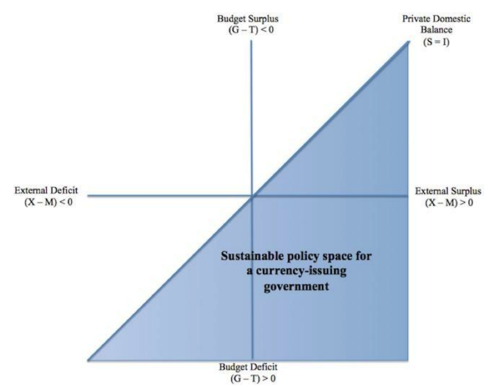

To see how these differing effects on private net saving matter, consider Figures 8 and 9 from Bill Mitchell that present a map of the sector financial balances equation. Figure 8 shows a graph (originally designed by Rob Parenteau here and here) in which the current account is on the horizontal axis, the government’s budget balance is on the vertical, and a diagonal line at the 45-degree point between the two balances is where the private domestic balance is zero. The blue portion below the diagonal is where the private domestic balance is positive, and the red above the diagonal is where the balance is negative. Figure 9 shows that for sustainability of the private sector—from a Minskyan perspective, which analyzes in detail the likelihood of financial distress resulting from the financial positions of private sector agents—on balance the private sector should be in the blue region. If we assume the private sector surplus is to be about 2% of GDP on average—the historical average in the US—then the government’s budget position should be negative unless the current account balance is at least 2% of GDP.

Figure 8

Sector Financial Balances Map

Figure 9

Sustainable Policy Space and the Sector Financial Balances Map

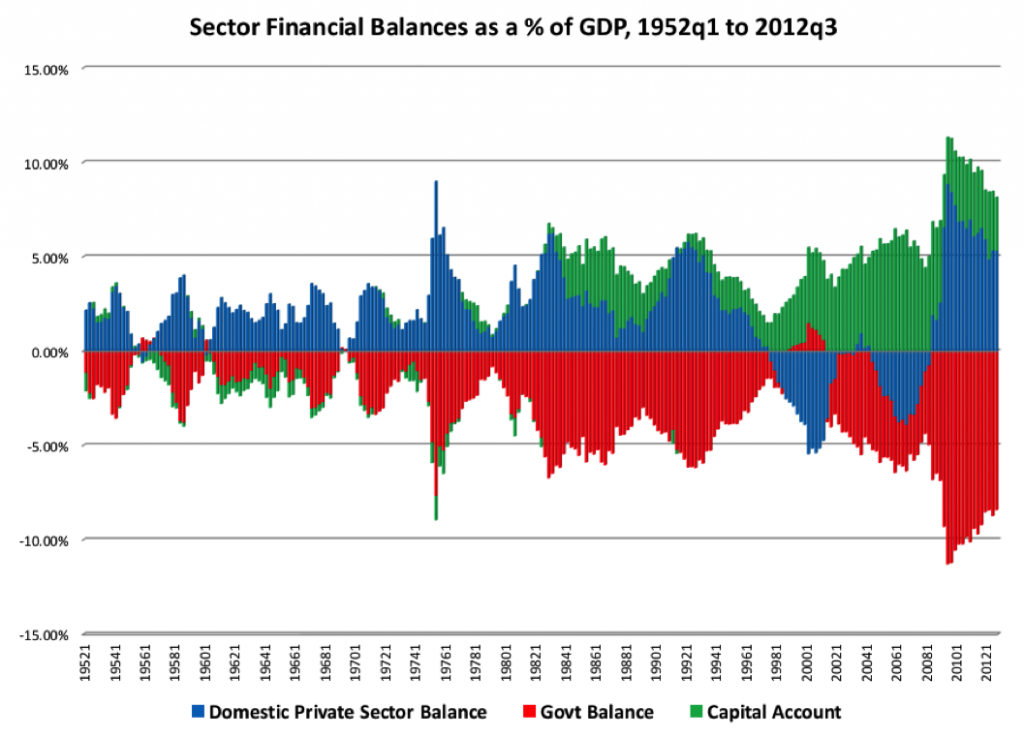

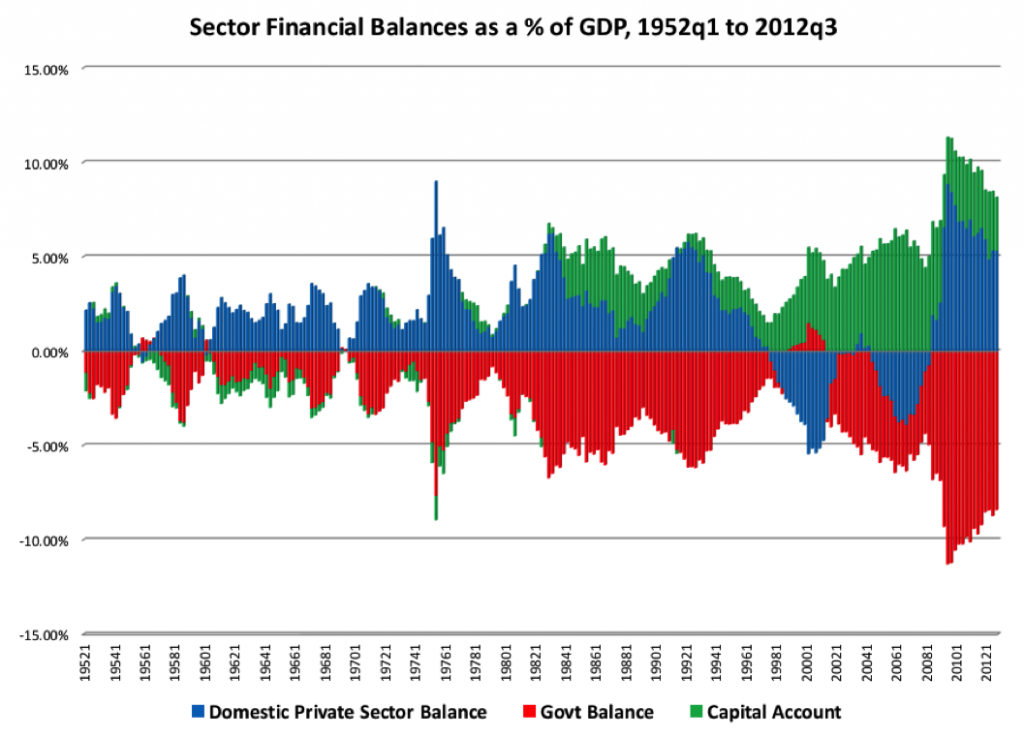

Furthermore, while the private sector might desire a 2% balance on average (for example), in reality this will fluctuate significantly from year to year or even quarter to quarter, as shown in Figure 10 (where the capital account is the opposite of the current account, so all three balances can be shown to generate mirror images around the origin). In other words, because desired private sector net saving at full employment will fluctuate significantly—rising a lot during recessions and falling considerably during expansions—fiscal policy should respond in kind in the opposite direction as a functional finance strategy would suggest. Relying instead on monetary policy only to end a recession requires the private sector to be willing to reduce its balance at the exact time that it typically desires to increase it (and this is not even to mention the acceleration of Minskyan fragility that can result from raising short-term interest rates and thus both the price of refinancing and cost of liabilities to financial institutions in order to halt an expansion that itself might have been the result of monetary policy’s encouragement of greater leverage earlier in the expansion).

Figure 10

In short, again the neoclassical policy mix of a dominant monetary policy driven by a Taylor Rule strategy and a passive fiscal policy balancing its budget intertemporally is found to be inadequate since it is based upon a highly simplified view of the macroeconomy that abstracts from multiple interest rates (the model has only 1), multiple and offsetting transmission mechanisms (again, the model has 1 only), Minskyan fragility (the model assumes no default risk in the private sector, as many have shown), how banks create money endogenously as a matter of accounting (the model assumes loanable funds), and stock-flow consistency across sectors of the economy (the model assumes financial crowding out results from fiscal deficits).

In the real world, fiscal policy must be able to respond to the private sector’s net saving desires at full capacity utilization; a monetary policy strategy based on the Taylor Rule actually does the opposite. This does not necessarily mean that there is no role for monetary policy if one is able to untangle the multiple and offsetting transmission mechanisms (and MMTers see a significant role for monetary policy in dealing with systemic risk and avoiding Minskyan fragility—and thus asset price bubbles—in the financial system, though this is also beyond the scope of this post), but it does mean that even in that case monetary policy should accommodate a functional finance strategy for fiscal policy somewhere in its reaction function used to set its strategy. To do otherwise is to implement a potentially unsustainable monetary policy that threatens the financial stability of the private sector (particularly when the private sector is heavily indebted) or results in direct and potentially perverse effects on public sector debt service relative to macroeconomic policy goals.

In part V, we will consider the implications of functional finance for CBO’s projections of the long-term government budget outlook.

機能ファイナンスと負債比率-パートIV

この5部構成のシリーズでは、負債比率と財政の持続可能性に関するMMTの視点を詳細に(警告!)、詳細に(別の警告-気がかりな警告!)探求します。 このアプローチは、マクロ経済政策のミックスと、ほとんどの新古典派経済学者が現在は持続可能でないと考えている財政政策と金融政策の両方の戦略を示唆しているが、最終的には、マクロ経済の安定化における財政政策の重要な役割に対するMMTの選好は、財政に関する伝統的な新古典主義の見解と一致することが示されている持続可能性。

この4番目の部分では、最初の3つの部分の内容を財政政策の機能的財務戦略と統合します。繰り返しますが、この部分は4つの中で最も長く詳細な部分です。 機能ファイナンスと財政の持続可能性

財政の持続可能性の概念、すなわち債務サービスの収orまたは少なくとも制限された成長を機能的金融と統合できるようになりました。 ただし、そのためには、まずリカードの財政政策の概念について簡単に説明する必要があります(MMTの見解については、Pavlina Tchernevaの論文を参照してください)。 2000年代に新古典派経済学を支配するようになった新しいコンセンサスの見解は、金利と財政政策を調整するためのテイラールールのような戦略を通じて金融政策が経済を管理し、インフレを目標としたマクロ経済政策ミックスを主張しました。現在および将来の税金を設定し、債務比率が際限なく上昇しないように支出することにより、その暫定的な予算の制約を遵守するだけです( ここでの政策ミックスについてもう少し)。 これを達成する財政政策は、新古典派によってリカード派と呼ばれています。 リカードの財政政策は、中央銀行のマクロ経済の管理を妨げません。ほとんどの場合、受動的であり、その時間的予算制約のみに内因的に反応します。

一方、財政政策が外生的に設定され、債務比率が際限なく上昇しないようにすることと矛盾する恒久的な黒字を実行する場合、これは非リカード的財政政策と呼ばれます。 これは明らかに、マクロ経済を管理しようとする中央銀行の試みを妨げます。 これは、リカード以外のシナリオで金利を上げてインフレを遅らせると、政府債務返済による総需要が増えるか、政府が債務不履行を避けるために「お金を印刷する」ため、インフレが増えるためです。

金融/財政政策のミックスに関するこの理解は、財政の持続可能性に関する文献で認められていますが、マクロ経済政策効果のより標準的な新古典派の分析ではこれがどれほど頻繁に無視されているかを戸惑っています。 実際、金融政策のショーのほとんどの新古典派の分析は、金利と支出が常に負の関係にあることを示唆しています。 2005年にステファニー・ケルトンとレックス・バリンジャーによって説明されたように★、しばしば忘れられているのは、非政府部門への利子の支払いは常に民間部門の収入であるという事実です。 ケルトンとバリンジャーは、「ケルトン曲線」と呼ばれるようになったものを提示します(図6)。これは、金利の上昇が支出を増やし、 GDP(「高債務GDP比率シナリオ」でYをY *に引き上げるi 1からi 2への動きのように)。

図6

ケルトン曲線は単に金利の上昇に関するものではなく、逆に作用します(つまり、i 2からi 1への移動)。これは、関心のある期間構造を削減するQE操作によって悪化した記録的な低金利で現在起こっています長期の財務省を翌日物準備残高に置き換えることによる金利。 ランディレイが数か月前に説明したように、低金利のマイナスの収入効果は財政刺激を相殺する上で重要です。

しかし、暗い側面があります。 低い預金率と高い手数料は、貯金を一掃しています。 知らないことは何も言っていません。 銀行での貯金の半分の割合を得ることができません。 確かに、住宅ローンの利率も下がりましたが、正味の効果は消費者の収入を流出させました。 以下はクレディ・スイスのレポートからの引用です。FRBのほぼゼロ金利の医療の副作用–過去数年間の個人の金利収入の崩壊。利息収入の減少は、実際には債務返済の節約の見積もりを小さくしています。 図表2では、家計の債務返済費用と個人の利子収入の推移を比較しています。 両方の総計は、ほぼ同時期(2008年中頃)に約1.4兆ドルに達しました。連邦準備制度の数字の分析によると、住宅ローンおよび消費者サービス費用を含む債務返済総額は、ピークから2,060億ドル減少しています。 利息収入の減少は、ピーク時から約4,700億ドルに達し、債務返済の低下による倍増の2倍以上になります。それを視点に入れましょう。 オバマの財政刺激策を覚えていますか? 2年間で年間約4,000億ドル。たとえば、GDPのほぼ3%です。 それが「機能した」かどうかについては大きな議論がありました。 本当にクレイジーな人だけが、それが私たちが実際に経験したよりもさらに悪い不況から私たちを救わなかったと信じています。QEは、オバマの刺激の半分に相当する総需要を経済から除去しています。 そして、それは2年間だけではありません。FRBがZIRPを追求している限り、年々継続しています。QEは毎年GDPの1.5%を奪うことで経済を刺激することになっていますか?過去20年間にZIRPを試した日本のケースで学んだように、非常に低い金利は、彼らが投入するよりも多くの需要を経済から奪い去っています。そのため、FRBはアクセルペダルのブレーキを誤解しています。ブレーキが、連邦機関はそれが経済により多くのガスを送っていると考える。 私たちが感謝できる唯一のことは、FRBがビュイックではなく人力車を運転しているということです。 それができる損害は致命的ではありません。誤解しないでください、私はZIRPに反対ではありません-私は常にZIRPを持っていますが、それは経済を刺激しないことを理解する必要があります。

また、先週、QEが2012年に民間企業からの収入のほぼ900億ドルを完全に削除したことを発見しました。

常にマクロ経済の安定化をもたらす利子率があると信じる新古典派とは異なり、MMTや他の人(水平主義者など)は、複数の利子率があるため、物事はもっと複雑だと考えます( どの利率がマイナスになるべきか?モデルには1つのレートしかありません)、それらすべての間の不明確な関係(QE3とその住宅ローン率への影響は不確実性の一例です)、そして最終的には考慮しなければならない複数のオフセット伝達メカニズム(さらに2つは短期的です)レートは、運転資金ファイナンスによる生産コストであり、CPIで測定される住宅価格に反比例します。 要するに、テイラールール戦略は金融政策の現実世界の状況を大幅に単純化しすぎており、その適用可能性は、一部の支出が金利の変化に負に関連しているという概念に明らかな真実があるにもかかわらず、非常に疑わしいと常に見られてきました。

テイラールールが過度に単純化されている世界では、金融政策のみが金融政策に基づいてマクロ経済政策をミックスしている一方で、財政政策の立案者が予算を時間的に受動的に均衡させることは過度に単純化され、破壊的ですらあります。 私たちの観点から見ると、財政政策は機能的財政戦略に従う必要があります。ここでは、失業、生産性(生活水準)、インフレに関する財政政策スタンスの結果であり、重要ではありません。負債比率の大きさ、それ自体。 適切に設計された機能的金融戦略には、強力な自動安定装置と、より大きな刺激または抑制が必要な状態に対処するためのオプションの「ツールキット」の両方が組み込まれます。

必然的に、これらの詳細はここでは範囲を超えています。ただし、実際には、Taylorルールは実際にはそれ以上ではないにしても、詳細に欠けていることに注意してください。 機能金融のように新古典派によって与えられた高い地位に反して、世界の仕組みの特定の観点に基づいて現実世界の戦略的決定を下す際に政策立案者を導くための一連の原則または基準ですインフレ率が上昇した場合、またはGDPギャップが低下した場合、およびその逆の場合、予想されるインフレ率の上昇よりも金利を引き上げます)。

機能的金融の観点は、(a)柔軟な為替レートの下で通貨発行政府が「健全な金融」のより伝統的な規則によって制約されず、(b)国家債務の利子はレートではなく金融政策変数であるということです。 「市場の力」または結束の自警団によって設定されます。 このように、高い負債比率の文脈で-そして、少なくとも議論のために米国が高負債比率の国であると仮定しましょう-考えられる異なるアプローチがあります。 これらは相互に排他的ではありませんが、実際には次の2つです。

まず、 GodleyとLavoieは、GDPが潜在能力を下回ると支出を引き上げ、GDPがそれを超えると支出を削減し、実際のインフレと目標インフレの差に応じて政府支出を調整する機能的財政財政政策「ルール」を設計します。 彼らは、この場合の利子率は安定した負債比率とこの機能的金融の「ルール」と一致することを示しています 。重要なのは、潜在的GDPに対して赤字が大きすぎる場合、機能的金融ルールは常に支出を削減することを認識することですまたは達成すべきインフレ目標と、このルールが偶然にも安定した負債比率を生み出すこと。 金利が高く、債務返済が増加している場合、潜在的なGDPがサイト内に収まるため、他の政府支出はルールに従って低下し、GDP を安定させ、ここでの文脈では、安定した債務比率と一致するあらゆるレベルで一次赤字を安定させます。 金利が低い場合、このルールにより、潜在的なGDPに達するまで他の支出を増やすことができますが、それ以上はできません。 つまり、機能的財務戦略を、テイラールールの財政政策バージョンのような単純なルールとして設定すると、真の機能的財政財政政策戦略は常にリカード的であることがわかります。

その後、GodleyとLavoieは、マクロ経済の安定化というタスクを単独で実行することにより、効果的な機能的金融ルールにより、金融政策が金融政策の分配効果に集中できるようになることを指摘しています。 彼らは、賃借人が(少なくとも理論的には)賃金労働者と同じ収入を得ることができる、生産性とインフレの成長率である「公正な」金利目標を提案した他の人々を引用している。 ここでの目的のために、多くの新古典派が示唆しているように、マイナスの利子率が分配にどのように影響するかに注意してください。 レイによって報告された財政刺激に対する相殺効果を超えて、民間部門の貯蓄者と債務者の間の分配は負の名目金利デフレを引き起こす可能性があります。その場合、国庫、定期預金などで収入が得られ、結果として支出が少なくなります。

もう一度、Godley / Lavoieと必ずしも排他的ではない第2の見解は、純粋にMMTに触発されたもので、Stephanie Keltonと私が2007年に提示したもので、永続的な低金利と機能的財務戦略が組み合わされています。 低金利は、債務比率や赤字に関係なく債務返済が際限なく上昇しないことを保証しますが、機能的金融戦略(Godley / Lavoieの場合と同様)は、低短期のインフレまたはデフレ効果のあらゆる組み合わせを相殺します最終的には金利が優勢になります(退職者の場合、ポートフォリオリターンの低下(発生する場合も発生しない場合もあります)には、ウォーレンモスラーの最近の提案など、財政政策を通じてそれを強化する方法があります)。 Godley / Lavoieのルールと一致して、真の機能的金融戦略を「中立」予算スタンスと呼びました。Godley/ Lavoieの機能的金融ルールに簡単に拡張して、「中立」機能的金融予算があることを示すことができるからです国債の利子率、したがって債務比率のスタンス。 ここで提案する低金利は、債務返済の増加に直面して一次赤字を迅速に削減することが政治的に実行可能でない政治情勢と一致している可能性があります。 そして、その場合、機能的財政の提案者は、高い負債比率の環境で金融政策に対抗するために財政措置を要求するよりも、単に目標金利を下げる方がはるかに簡単であるため、持続不可能な財政政策ではなく、持続不可能な金融政策に言及します。

図7

(彼らが定義したように「公正な」金利よりも低金利を好むのは、ここで省略しなければならない技術的なポイントですが、後者を支持する一部の水平主義者との議論では、 「公正な」レートは必ずしも翌日物レートではないため(必ずしも長期的なレートである可能性があります)、MMTの提案では翌日物レートが参照されます。

金融政策のテイラールールと新古典派の財政政策ミックスのバランスのとれた時間間予算が問題となるもう1つの理由は、セクターの財政バランスと経済のセクター全体のストックフローの一貫性です。 MMTの文献を読んでいる人なら誰でも、すでに民間部門の黒字または純貯蓄=政府の赤字+経常収支の会計上のアイデンティティを知っています 。

簡単に要約すると、重要な点は、経常収支の黒字や政府の赤字がなければ、国内民間部門はネットセーブができないということです。 ありがたいことに、柔軟な為替レートの下で通貨を発行する政府は、経常収支の黒字がなくても予算の赤字を実行することでこの要望に応えることができ、経常収支の赤字があれば民間セクターを可能にするためにさらに大きな赤字を実行することができますネットセーブ。 貯蓄または民間部門の投資支出と混同しないように(残念ながら多くの人がこれを行っていますが)、純貯蓄は、単に部門全体の収入が部門全体の収入に対してどれだけ支出しているかを示す指標です。 純貯蓄の減少は、ミンスキーヘッジヘッジから遠ざかる動きのシグナルである傾向があり、逆も同様です。

しばしば認識されない金融政策と財政政策の重要な違いは、金融刺激策は民間部門の純貯蓄の削減を通じて「機能」するのに対し、財政刺激策は民間部門の純貯蓄の増加を通じて機能するということです(詳細はこちら )。 つまり、経済をシミュレートするためにテイラールール戦略を介して金利を引き下げることは、たとえば、所得に比べて両方のケースで企業資本支出または家計支出の増加をもたらす場合にのみ「機能」します。 これにより、最終的に連邦政府への税収が増加し、それによって政府の予算バランスが改善され、民間部門の純貯蓄が削減されます(技術的な余地はありますが、民間部門の貯蓄は、会計上の定義により、事業資本支出とともに全体的に増加します)しかし、民間部門の純貯蓄は減少しました。 財政政策については、民間部門の所得を最初に引き上げる所得の移転または減税があります。その結果、その後の支出は追加の税収となり、民間部門の純貯蓄の初期増加をいくらか相殺しますが、全体的な効果は、非常に大きな乗数効果の場合を除いて増加します(おそらく理論上のみ発生します)。

プライベートネットの貯蓄問題に対するこれらの異なる影響を確認するには、セクターの財務収支方程式のマップを示すビルミッチェルの図8と9を検討してください。 図8は、グラフ(元はこことここでロブパレントーによって設計された )を示しています。このグラフでは、経常収支は水平軸にあり、政府の予算収支は垂直にあり、2つの収支間の45度の対角線は民間の国内残高はゼロです。 対角線の下の青い部分は個人の国内残高がプラスである部分であり、対角線の上の赤はバランスがマイナスである部分です。 図9は、民間部門の持続可能性のために、民間部門のエージェントの財政状態に起因する財政的苦痛の可能性を詳細に分析するミンスキーの観点から、民間部門はバランスのとれた青い地域にあるべきであることを示しています。 民間部門の黒字が平均でGDPの約2%(米国の過去の平均)であると仮定すると、経常収支がGDPの少なくとも2%でない限り、政府の予算ポジションはマイナスになります。

図8

セクターの財政収支マップ

図9

持続可能な政策空間とセクターの財政収支マップ

さらに、民間セクターは平均で2%のバランスを望んでいる場合がありますが(図10)(図10に示すように、実際にはこれは年ごとまたは四半期ごとに大きく変動します)経常収支であるため、3つの天びんすべてを表示して、原点周辺の鏡像を生成できます)。 言い換えれば、完全雇用時の望ましい民間部門の純貯蓄は大幅に変動するため(景気後退期には大幅に上昇し、景気拡大期には大幅に低下する)、財政政策は機能的金融戦略が示唆するように反対方向で現物で対応すべきである 景気後退を終わらせるためだけに金融政策に頼るのは、民間セクターが通常それを増やしたいと思っている正確な時期にバランスを減らそうとすることを必要とします(そしてこれは、ミンスカンの脆弱性が加速することで加速することは言うまでもありません)短期金利、したがって借り換えの価格と金融機関に対する負債のコストの両方は、それ自体が金融政策による拡大の初期段階でのレバレッジ拡大の促進の結果であったかもしれない拡大を止めるためです。

図10

要するに、テイラールール戦略によって推進される支配的な金融政策と、その予算を一時的に均衡させる受動的な財政政策の新古典派の政策ミックスは、複数の利益から抽象化されるマクロ経済の非常に単純化されたビューに基づいているため、不適切であることがわかりましたレート(モデルには1のみ)、複数のオフセットトランスミッションメカニズム(再び、モデルには1のみ)、Minskyanの脆弱性(多くの人が示しているように、このモデルは民間部門でデフォルトリスクを想定していない)、銀行が内生的にお金を生み出す方法会計の問題(モデルは貸付可能な資金を想定)、および経済のセクター全体での在庫フローの一貫性(モデルは財政赤字からの財政的混雑の結果を想定)。

現実の世界では、財政政策は、全能力を活用した場合の民間部門の純貯蓄の要望に対応できなければなりません。 テイラールールに基づく金融政策戦略は、実際には逆のことを行います。 これは、複数の相殺メカニズムを解くことができる場合、必ずしも金融政策の役割がないことを意味するわけではありません(そして、MMTerは、システミックリスクに対処し、ミンスキーの脆弱性を回避するために金融政策の重要な役割を見るため、資産価格のバブル-金融システムでは、これもこの投稿の範囲外ですが)、その場合でも、金融政策は、その戦略を設定するために使用される反応関数のどこかで、財政政策の機能的金融戦略に対応する必要があることを意味します そうでなければ、民間部門の財政の安定性を脅かす可能性のある潜在的に持続不可能な金融政策を実施することです(特に民間部門が多大な負債を抱えている場合)、またはマクロ経済政策の目標に対して公共部門の債務返済に直接的かつ潜在的に悪影響を及ぼします。

パートVでは、CBOの長期的な政府予算の見通しの予測に対する機能的ファイナンスの影響を検討します。

★★

#8:124~8

MMT Primer発売記念! L・ランダル・レイ:「日本はMMTをやっているか?」 – 道草

2019/7/2

…

大きな赤字(負債)比率を生成するためには、醜い方法と良い方法の両方がある。彼らが理解していないのはこのことだ。MMTは長い間これを主張してきたが、理解がほとんど進んでいない。その主な理由は、私たちが平易な英語を使ってきたからだろうか。経済学者は読解が苦手なのだ。彼らにとっては、図と数学は必須だ。ならば以下、彼らの役に立つ書き方をしてみよう。

[この図はMitchell2019にはない]

で、名前を付けてみた。ラッファー曲線(Laffer Curve) 、フィリップス曲線 (Phillips Curve) ではないが、名付けてレイ曲線 (Wray Curve) だ。バーでナプキンに描いたのではなく、昨夜寝る前にメモ帳に書いたのだ。

経済が初期状態として点Aにあると仮定する。日本の場合、赤字比率が5%の、成長率が1%というところだ。現在、安倍首相が消費税を課したり米国が景気低迷に陥ったりで日本の成長率は低下するとする。すると経済成長が鈍化し、赤字比率は上昇するにつれ、経済は図の点Bに向かって左に移動する。

成長の鈍化は、家計や企業を脅かし、貯蓄しようと支出を減らし税収を減少させる。成長率の鈍化はまた輸入の減少にもつながり、経常収支はいくぶん「向上」する。部門間収支を見ると、政府収支は赤字(例えば7%の財政赤字)、経常収支は黒字(例えば4から5%)とすると民間部門の黒字は12%(他の二部門の合計)となる。

以上は財政赤字を増やす「醜い」方法。日本式だ。それは、まるで出血させれば病気を治すだろうといつまでも出血させているようなものだ。

MMTの対案とは何か? 企業と家計の自信を回復させることにターゲットを絞った、計測を伴う刺激策だ。老後の生活を保障する社会保障のセーフティーネットの充実。雇用と適正な賃金を確保するためコミットメントを作り直す。労働力の減少に対応するために出生を促進するか、移民を奨励するかする。グリーン・ニューディール政策を実施し、カーボンレスな未来へ移行する。

この場合、点Aから点Cに向かう曲線に沿うことになり、「良い」方法で財政赤字が増加し、成長率は改善する。

但し、赤字の増加は一時的なものであろうことに注意せよ。家計や企業が支出を始めるので、民間黒字が減少する。輸入が増えれば、経常収支の黒字も減る。だから税収が増えるだろう。税率を上げるからではなく、所得が増えるからだ。財政赤字は、国内民間部門の黒字が減少するにつれ減少するだろう。赤字の減少が正確にどの程度になるかは、民間部門の黒字と経常収支の黒字の動向にかかっていて、単にそれらの合計と等しくなる。

上のグラフで言えば、レイ曲線が右にシフトする。点Aの赤字比率における成長率はより高いということになろう。点Aにおける「自然な」赤字比率は存在しない。それは他の二部門の収支次第に依存する。

米国で考えると点Aは、日本と比較すると成長率が高く赤字比率は同程度というところだ。今の米国の経常収支はもちろんマイナスなので、この点では日本より財政赤字率が大きくなる方向。また、どこの成長率をとっても、民間部門の黒字は日本のそれよりも小さく、この点では財政赤字率が小さくなる方向。米国の赤字比率はこの二つの効果が相殺し合い、日本と同程度ので約5%で、成長率は日本より高い。

ここで、「逆ラッファー曲線」のようなものを勧めているのではないことに注意されたい。ラッファー曲線とは、減税は「それ自体を賄う」以上の効果があり、トリクルダウンにより財政赤字を解消するのに十分な歳入増がもたらされるとするものだった。私は、財政支出を増やし経済を刺激すれば税収が増え、赤字比率が元の水準(以下)に戻ると主張しているのではない。実際にどうなるかは、他の二部門の収支に依存している。

財政赤字の大きさそのものは重要ではない。重要なのは、政府の財政政策が公益と民益の追求に役立つかどうかだ。財政赤字の数字は、常に他の二部門との「ぴったりバランス」に常に調整される。この等式は、低すぎる成長率(デフレの)状態でも高すぎる成長率(インフレの)状態でも、どんな成長率になる場合でも成立する。

また、部門間バランス式は、どんな財政赤字比率にも当てはまる。ゆえに、景気刺激策に首尾よく成功すればレイ曲線は右にシフトする可能性が高いのだが、成長率が上昇するにつれ財政赤字比率がどこに落ち着くかを正確に予測することはできない。

このグラフで最も重要なことは、赤字比率がある値だとしても、少なくとも二つの異なる成長率がありえるものとして存在するという理解だ。赤字比率が同じでも、成長率が「醜い」ことになる道もあれば、「良い」ことになる道もある。日本は財政拡大を恐れるあまり、「醜い」赤字を出すための経済を運営し続けている。

財政赤字に関するこの議論の詳細は、新しい教科書のここを参照。 Mitchell, Wray and Watts, Macroeconomics (Macmillan International, Red Globe Press), Chapter 8, 特に pp. 124-128.(訳注 この部分の日本語訳がこちら)

#8:124~8

…

____

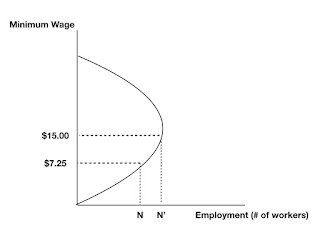

もう一つのケルトンカーブ

| Stephanie Kelton (@StephanieKelton) |

|

Republicans assert that we're on the wrong side of the Laffer Curve so lower tax rates will boost the economy. I assert that we're on wrong side of the Kelton Curve (self-named 😉) pic.twitter.com/TgR749lAIL

| |

https://twitter.com/stephaniekelton/status/932674258811187200?s=21

0 Comments:

コメントを投稿

<< Home