「ふざけんな!金返せ!」古代メソポタミアの粘土板に刻まれた文字の解読を行ったところ、顧客のクレームであることが判明★

MESOPOTAMIAN ECONOMICS

★★

http://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub363/item1514.html

メソポタミア経済

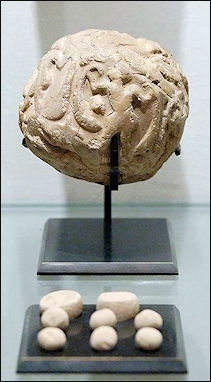

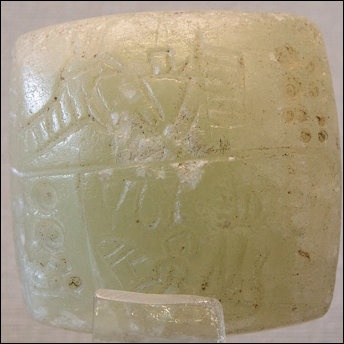

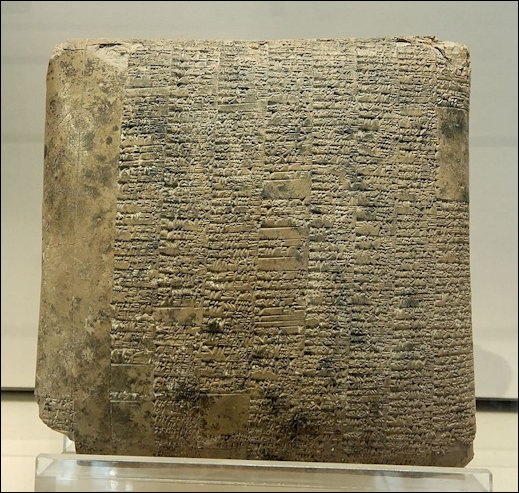

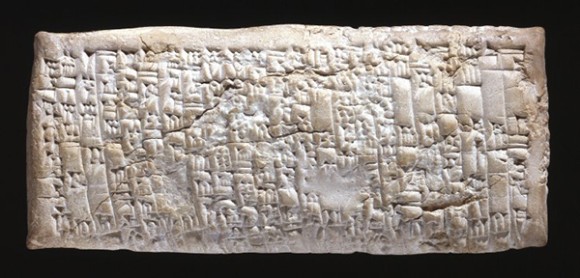

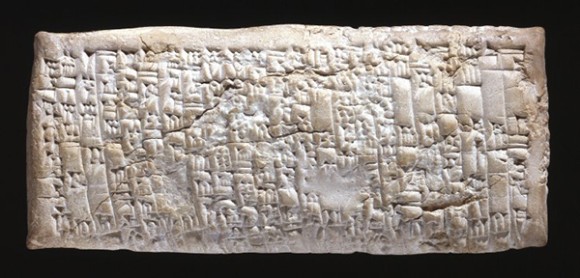

20120208-Accountancy_clay_envelope_Louvre.jpg

会計粘土封筒(経理粘土封筒)

メソポタミアは、都市や記念碑の建設、芸術品や工芸品の生産、商人、寺院、君主の支援に活用できるほどの労働力が解放されるほど、余剰作物が生産された最初の場所でした。

シュメール人は、世界初の文章を使用して経済取引を記録し、数千マイルに及ぶ貿易ネットワークに参加しました。バビロニア人は、商業を拡大し、初期の銀行システムを開発したと信じられています。

初期の執筆のほとんどは、商品のリストを作成するために使用されました。書記体系は、社会の円滑な運営を維持するために、税、配給、農産物、および貢物に記録を保存する必要がある、ますます複雑化する社会に対応して発展したと考えられています。

シュメール語の記述の最も古い例は、買い手と売り手の間の取引を記録した売上手形でした。トレーダーが10頭の牛を売ったとき、彼は10番のシンボルと絵文字の牛のシンボルを持つ粘土板を入れました。

メソポタミア人は、世界初の偉大な会計士としても説明できます。神殿で消費されたすべてのものを粘土板に記録し、神殿の保管庫に置きました。回収されたタブレットの多くは、このようなアイテムのリストでした。製品にはロイヤルシールが貼られています。

貿易を見る

本:スネル、ダニエルC.、元帳および価格:初期メソポタミア商人のアカウント。ニューヘブン:エール大学出版局、1982年。

このウェブサイトに関連記事があるカテゴリ:メソポタミアの歴史と宗教(35件の記事)factsanddetails.com;メソポタミアの文化と生活(38記事)factsanddetails.com;最初の村、初期の農業と青銅、銅と後期石器時代の人間(50記事)factsanddetails.com古代ペルシャ、アラビア、フェニキア、近東文化(26記事)factsanddetails.com

メソポタミアに関するウェブサイトとリソース:古代史百科事典ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia;メソポタミアシカゴ大学サイトmesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu;大英博物館mesopotamia.co.uk;インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミアsourcebooks.fordham.edu;ルーヴル美術館

louvre.fr/llv/oeuvres/detail_periode.jsp;メトロポリタン美術館metmuseum.org/toah;ペンシルバニア大学考古学人類学博物館penn.museum/sites/iraq;シカゴ大学東洋研究所

uchicago.edu/museum/highlights/meso;イラク博物館データベースoi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/dbfiles/Iraqdatabasehome;ウィキペディアの記事ウィキペディア。 ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Oriental Institute Virtual Museum oi.uchicago.edu/virtualtour;王の墓からの宝oi.uchicago.edu/museum-exhibits;古代近東美術メトロポリタン美術館www.metmuseum.org

考古学のニュースとリソース:Anthropology.net anthropology.net:人類学と考古学に興味のあるオンラインコミュニティにサービスを提供しています。 archaeologica.org

archaeologica.orgは、考古学のニュースと情報の良い情報源です。ヨーロッパの考古学archeurope.comは、教育リソース、多くの考古学主題に関するオリジナル資料を特色とし、考古学イベント、スタディツアー、フィールドトリップ、考古学コース、ウェブサイトおよび記事へのリンクに関する情報を持っています。考古学雑誌archaeology.orgには、考古学のニュースと記事があり、

Archaeological Institute of Americaの出版物です。 Archaeology News Network archaeologynewsnetworkは、考古学に関する非営利のオンラインオープンアクセスのコミュニティ向けニュースWebサイトです。英国考古学雑誌british-archaeology-magazineは、英国考古学評議会が発行する優れた情報源です。現在の考古学雑誌archaeology.co.ukは、英国の主要な考古学雑誌によって作成されています。 HeritageDaily heritagedaily.comは、オンラインの遺産と考古学の雑誌で、最新のニュースと新しい発見を強調しています。 Livescience livescience.com/:考古学的なコンテンツとニュースが豊富な一般的な科学ウェブサイト。過去の地平線:考古学や遺産のニュース、その他の科学分野のニュースを網羅したオンラインマガジンサイト。 Archaeology Channel

archaeologychannel.orgは、ストリーミングメディアを通じて考古学と文化遺産を調査しています。 Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu:非営利組織によって公開され、先史時代の記事が含まれています。 Best of History Webサイトbesthistorysites.netは、他のサイトへのリンクの優れた情報源です。 Essential Humanities essential-humanities.net:セクションPrehistoryを含む、歴史と美術史に関する情報を提供します

メソポタミアの産業、資源、ビジネス

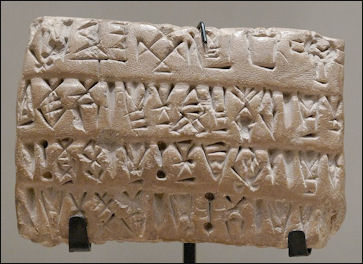

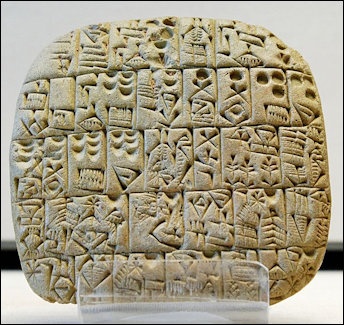

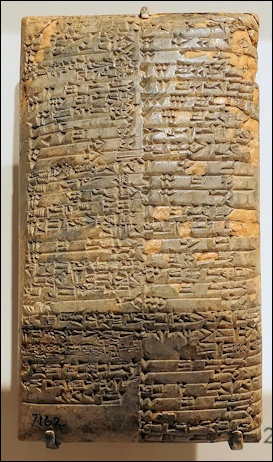

20120208-Economic_tablet_Susa_Louvre_.jpgスーサの経済タブレット

手作り品の組織的な生産は、メソポタミアで最初に開発されました。シュメール人は製品を製造しました。何千人もの労働者による羊毛の製織は、大規模産業向けとみなされています。

シュメールo上流に戻ります。そのため、木材ではなく皮のボートを作ります。アルメニアに戻ると、彼らは次の航海のために新鮮なボートを作ります。 I.195:

メソポタミアのお金

シュメール人の経済的測定単位には、1)gur(26ブッシェルにほぼ等しい量の単位)がありました。 2)マグカップまたはクー、シルバーまたはマネー。および3)ジンまたはギグ、シェケルにほぼ等しいお金として使用される小さなaの頭。 John Alan Halloranはsumerian.orgに次のように書いています。「Ur III時代から、さまざまな商品の異なる量の銀相当量を与えるさまざまな場所や時代のタブレットがあります。UrIII期間中、州は主要債権者でした。州は個人に非常に多くの土地または非常に多くの動物を供給し、個人はその後州に返済しなければなりませんでした。 [出典:John Alan Halloran、sumerian.org]

シルバーリングは、最初のコインが打たれる約2000年前の通貨としてメソポタミアとエジプトで使用されていました。考古学者の中には、メソポタミアの裕福な市民が紀元前2,500年頃、またはおそらく数百年前にお金を使ったと示唆している人もいます。デ・カルブにあるイリノイ州北部の歴史家マービン・パウエルはディスカバーに、「メソポタミアの銀は今日の私たちのお金のように機能します。交換の手段です。 、発見、1998年10月]

メソポタミアで使用されたシルバーリングと、紀元前7世紀にアナトリアのリディアで最初に生産された最初のコインの違いリディアのコインにはリディアの王のスタンプがあり、したがって、信頼できるソースによって固定値を持つことが保証されていました。王の切手がなければ、人々は見知らぬ人から額面どおりにお金を受け取ることに消極的でした。

考古学者は、古代のお金に関する情報を整理するのに苦労しました。なぜなら、陶器や調理器具とは異なり、考古学的な場所で豊富に供給されていて、それらを捨てなかったからです。

プロトマネーの開発

20120208-Clay_accounting_tokens_Susa_Louvre_n1.jpg粘土会計トークン

最も初期の貿易形態は物々交換でした。最も初期の知られているプロトマネーは、近東の村の家や市の寺院の床から発掘された粘土トークンです。トークンはカウンターとして機能し、おそらく執筆前に使用された約束のメモとして機能しました。トークンのサイズと形状はさまざまです。

最初の都市が台頭する前に肥沃な三日月に住んでいた初期メソポタミア人は、穀物、人間の労働、ヤギや羊などの家畜の3つの主要な貿易財の異なる量を表す5つのトークンタイプを使用していました。

イランのスーサで発見された世界初のお金と一部の学者によって説明された粘土トークンは、紀元前3300年の日付が付けられています。 1頭は羊1頭に相当します。他のものは、油の瓶、金属の量、蜂蜜の量、および異なる衣服を表しています。

メソポタミアの都市には、蜂蜜、カモ、ヒツジのミルク、ロープ、衣服、パン、織物、家具、マット、ベッド、香水、金属など、16種類のトークンとサブカテゴリがありました。

お金のアイデアとその背後にあるアイデアの開発

南西ミズーリ州立大学のエコノミスト、トーマス・ウィリックは、ディスカバーに次のように語っています。つまり、1足のサンダルは10日付、1クォートの小麦、2クォートのビチューメンなどになります。」

「最高の価格はどれですか?それは非常に複雑なため、人々が良い取引をしているかどうかわかりません。歴史上初めて、私たちは大量の商品を手に入れました。そして、初めて、それが人間の心を圧倒する多くの価格。人々は価値を述べる何らかの標準的な方法を必要としていました。」

メソポタミアでは、紀元前3100年からの間に銀が価値の標準になりました。紀元前2500年大麦と一緒に。銀が使用されたのは、それが貴重な装飾材料であり、携帯可能であり、その供給が年ごとに比較的一定で予測可能であったためです。

紀元前2500年頃銀のシェケルが標準通貨になりました。錠剤には、木材と穀物の価格が銀のシェケルで記載されていました。シェケルは、重量で約3分の1オンス、つまりわずか3ペニーに相当しました。 1か月の労働には1シェケルの価値がありました。 100分の3シェケルで販売されている1リットル。 10から20シェケルで売られた奴隷。

シェケルが交換手段として登場してから間もなく、王は罰としてシェケルに罰金を課し始めました。紀元前2000年頃、エシュヌナ市で、別の男の鼻を噛んだ男が60シェケルの罰金を科されました。別の男の顔を平手打ちした男は、20シェケルを払わなければなりませんでした。

メソポタミアのリングマネー

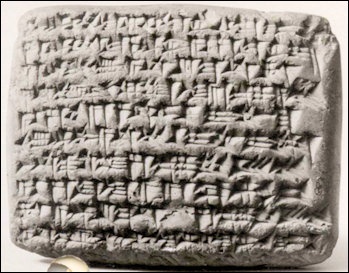

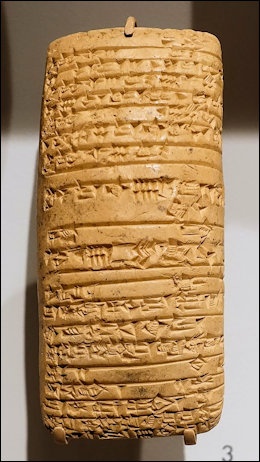

20120208-Reciept_for_clothes_IMG_0076.jpg衣服の領収書

シェケルのearly明期には、人々は金属片を袋に入れて持ち運び、反対側の対策として石を使ったスケールで量を測定しました。紀元前2800年から紀元前2500年銀の破片は標準重量で鋳造され、通常はタブレットにハーと呼ばれるリングまたはコイルの形をしていました。 1から60シェケルの価値があるこれらの指輪は、主に金持ちが大きな購入をするために使用しました。それらはいくつかの異なる形で来ました:三角形の尾根を持つ大きなもの、細いコイル。

ユーフラテス川の町シッパルの3,700歳のタブレットは、両親から受け取った普通の労働者の60ヶ月分の賃金に相当する銀の指輪のある土地を買った女性の売り上げを記録しました。

彼らの手形を支払うために、普通の人々はスズ、銅または青銅で作られたあまり価値のないお金を使いました。大麦は通貨としても使用されました。それの利点は、小さな計量エラーがほとんど違いをもたらさず、誰かをだましにくいことでした。

お金の使用は、都市国家と王国の間、そしてメソポタミア、エジプトとパレスチナの間の貿易を容易にしました。

お金の問題

シルバーの主な問題は、それが非常に価値があり、計量誤差や不純なシルバーが大量の価値を失うことにつながることです。一部の人々は、他の金属を金や銀に追加したり、そっくりの金属を置き換えたりすることで、意図的に他人をだまそうとしました。

詐欺と不正行為は古代世界で非常に一般的であったため、旧約聖書には8つの聖句があり、うろこを改ざんしたり、重い石をライターに置き換えることを禁じています。

多くの場合、人々は借金に陥りました---借金に陥ったためにさまざまなトラブルに直面している人々を説明する多数のタブレットレターに基づく結論多くの債務者が奴隷になりました。バビロンでは状況があまりにも手に負えなくなったため、ハンムラビ王は借金のために3年以上奴隷にされることはできないと命じました。他の都市では、住民は借金で苦しんでおり、すべての未払いの法案に対して一時停止を発行しました。

20120208-zavazi_hematit_Irak.JPGザバジヘマタイト

古代バビロニアの寺院で始まった現代の銀行業

古代エジプトとメソポタミアでは、金、銀、その他の貴重品が保管のために寺院に預けられました。銀行の歴史は、紀元前2千年紀前半の古代バビロニア神殿にまで遡ることができます。ハンムラビの時代のバビロンには、神殿の司祭による融資の記録があります。神殿は寄付と税収を受け取り、大きな富を蓄積しました。次に、これらの商品を未亡人、孤児、貧しい人々などの困inしている人々に再配布しました。 [出典:MessageTo Eagle 2016年3月7日、古代史の事実]

千年後、寺院を経営した司祭たちはお金をたくさん持っていたので、銀行業の概念がアイデアとして浮上しました。紀元前18世紀のハンムラビの頃、聖職者は人々が融資を受けることを許可しました。古いバビロニアの神殿は、困poorしている貧しい人々や起業家に多くの融資を行いました。とりわけ、ハンムラビ法典は利付ローンを記録しました。」

銀の貸付金を詳述する楔形のタブレット上のテキストc。紀元前1800年、「3 1/3シルバーシグロイ、1/6シグロイ、シグロイあたり6粒の利子で、Ikun-pi-Istarの召使であるAmurritumがIlum-nasirから貸し出しを受けました。 3か月目に彼女は銀を支払わなければならない。」1 sigloi = 8.3グラム。

ローンは、個人よりも低いローンよりも低い市場金利で引き下げられ、債権者が利息を返済する代わりに寺院に食料を寄付するよう手配されることもありました。バビロニアのエギビの家の楔形文字の記録には、紀元前1000年以降に発生したとされる家族の財務活動が記載されています。ダリウス1世の治世中に終わると、「貸し家」に「プロフェッショナルバンキング」に携わる家族が現れます。

メソポタミアの物件

クロード・ヘルマンとウォルター・ジョンズはブリタニカ百科事典に次のように書いています。「都市の神はもともとその土地の所有者であり、灌漑可能な耕地の内側の輪と牧草地の外側の縁に囲まれ、市民は彼の入居者でした。神と彼の副王である王は、長い間借家人の邪魔をやめ、ナチュラリア、株、金銭、奉仕の会費に満足していた。最も初期のモニュメントの1つは、大規模な地所の王が息子のために購入したことを記録し、公正な市場価格を支払い、高価な衣服、プレート、貴重な家具の所有者にハンサムな謝礼金を追加します。 [出典:Claude Hermann Walter Johns、バビロニア法— The Hammurabiのコード。ブリタニカ百科事典第11版、1910〜1911年<^>]

Hammurbai Codeは「土地の完全な個人所有権を認めているが、どうやら土地を投票者、商人(および居住外国人?)に保持する権利を拡張しているようだ。しかし、すべての土地はその固定料金の対象として売却されました。しかし、王はチャーターによってこれらの告発から土地を解放することができました。これは、国家にふさわしい人々に報いるための頻繁な方法でした。これらの憲章から、土地に課せられる義務について私たちが知っているほぼすべてを学ぶことができます。国家は、軍隊とコルベ、および現物の会費を男性に要求しました。 <^>

「明確なエリアは、ボウマンと一緒に見つけるためにバインドされていました彼のリンクされたパイクマン(両方のシールドを持っている)とキャンペーンの供給をそれらに提供します。この地域は、紀元前8世紀には早くも「弓」と呼ばれていましたが、その使用法はずっと以前のものでした。後に、特定の地域から出馬する予定でした。男は非常に多く(6回?)奉仕するしかありませんでしたが、土地は毎年男を見つけなければなりませんでした。奉仕は通常奴隷と農奴によって解雇されたが、アメル(そしておそらくムスケヌ)は戦争に出た。 「弓」は数十と数百にグループ化されました。コルベはあまり規則的ではありませんでした。ハンムラビの手紙はしばしば免除の主張を扱っています。群れを管理する宗教当局者と羊飼いは免除されました。運河、橋、岸壁などを修理するために、川岸の所有者に特別な責任があります。

ハンムラビコードの所有権

畑のプレスメリアセール

クロード・ヘルマンとウォルター・ジョンズは、ブリタニカ百科事典に次のように書いています。売却とは、購入金と引き換えに購入品を配達することでした(スタッフ、キー、または運送証書に象徴される不動産の場合)。クレジットが与えられた場合、借金として扱われ、売り手がローンとして担保し、買い手が返済するために彼が債券を与えた。 [出典:Claude Hermann Walter Johns、バビロニア法— The Hammurabiのコード。ブリタニカ百科事典第11版、1910〜1911年<^>]

「規範は、文書または証人の宣誓によって立証されない主張を認めません。買い手は売り手の称号を納得しなければなりませんでした。弁護士の権限のない未成年者または奴隷から購入した(または預け入れで受け取った)場合、彼は泥棒として処刑されます。品物が盗まれ、正当な所有者がそれらを回収した場合、売り手とその販売証書または証人を作成して、購入を証明しなければなりませんでした。さもなければ、彼は泥棒と判断されて死にます。彼が購入を証明した場合、彼は財産を放棄しなければならなかったが、売り手に対する救済措置をとるか、または彼が死んだ場合、彼の財産から5倍を取り戻すことができた。海外で奴隷を買った男は、彼がバビロニアから盗まれたり捕らえられたりしたことを発見するかもしれません。彼が封建的所有物、または公然の区に属する財産を購入した場合、彼はそれを返還し、彼がそれのために与えたものも没収しなければなりませんでした。彼は1か月(後、100日)以内にベンヌ病に襲われた奴隷の購入を拒否し、3日間の女性奴隷の承認を得ました。所有権の不備または開示されていない責任は、いつでも販売を無効にします。 <^>

「土地所有者は自分たちの土地を頻繁に耕作しましたが、夫を雇うか、そのままにしておくかもしれません。夫は適切な耕作を行い、平均的な作物を育て、畑をうまく耕さなければなりませんでした。収穫に失敗した場合、コードは法定利益を修正しました。規範がテナントに偶発的な損失が発生したことを制定したとき、土地は固定賃料で貸されるかもしれません。利益を分配する場合、家主と入居者は、規定の利益分配に比例して損失を分配しました。借家人が家賃を払って土地を十分に傾けたままにしておくと、家主はサブレッティングを妨害したり禁止したりすることはできませんでした。荒地は埋め立てられ、テナントは3年間家賃が無料で、4年目には規定の家賃を支払いました。借地人が土地の返還を怠った場合、コードは、土地を適切に引き渡さなければならないと制定し、法定賃料を修正しました。庭やプランテーションは同じ方法で同じ条件の下で放置されました。しかし、デートグローブの場合、4年間の無料在職期間が許可されました。メタヤーシステムは、特に寺院の土地で流行していました。家主は、散水機を耕し、作業するための土地、労働者、牛、カート、脱穀または他の道具、種子トウモロコシ、労働者のための配給、および牛のための飼料を見つけました。テナント、またはスチュワードは、通常、彼自身の別の土地を持っていました。彼が種、配給または飼料を盗んだ場合、コードは彼の指を切り落とすことを制定しました。彼が道具を割り当てたり販売したり、牛を貧しくしたり、貸したりした場合、彼は重度の罰金を科され、支払いのデフォルトでは、

畑の牛によって破片に引き裂かれたと非難されるかもしれません。家賃は契約どおりでした。 <^>

ハンムラビコードの支払いと負債

クロード・ヘルマンとウォルター・ジョンズは、ブリタニカ百科事典に次のように書いています。ただし、債務者は法定規模に応じて農産物の支払いを許可する必要があると制定されました。債務者がお金も作物も持っていない場合、債権者は商品を拒否してはなりません。 [出典:Claude Hermann Walter Johns、バビロニア法— The Hammurabiのコード。ブリタニカ百科事典第11版、1910〜1911年<^>]

売渡証

「銀行からの支払い、または預金に対する草案による支払いが頻繁に行われました。債券支払うことは交渉可能として扱われました。利息aは、差し迫ったニーズのために神殿や裕福な土地所有者による前進に対してめったに請求されませんでしたが、これはメタイヤーシステムの一部であったかもしれません。借り手はテナントだったかもしれません。この種の延滞ローンについては、非常に高い金利で利息が請求されました。商人(場合によっては寺院も)は通常のビジネスローンを作り、20から30パーセントを請求しました。 <^>

「債務は債務者の人に確保されました。債務者のとうもろこしへの拘束はコードによって禁止されていました。債権者はそれを返還しなければならないだけでなく、彼の違法行為は彼の主張を完全に没収した。働く雄牛の抑制と同様に、債務に対する不当な押収が科された。借金のために押収された債務者は、借金、彼の妻、子供、または奴隷を取り払うための手腕または人質として指名される可能性があります。債権者は、妻または子供を3年間だけ仮死状態にすることができました。債権者の所持中にマンシピウムが自然死した場合、債権者に反対する主張はない。しかし、もし彼が残虐行為による死の原因であったなら、彼は息子に息子を与えるか、奴隷にお金を払わなければなりませんでした。彼女が主人公の子供を産んだ奴隷の少女でない限り、彼は奴隷の人質を売ることができた。彼女は彼女の所有者によって償還されなければなりませんでした。 <^>

「債務者は自分の財産を誓約することもでき、契約ではしばしば畑や作物を誓約しました。しかし、コードは、債務者が常に自分で作物を取り、それから債権者に支払うべきであると制定しました。収穫が失敗した場合、支払いは延期され、その年の利子は請求されません。債務者が自分で畑を耕さなかった場合、耕作の費用を支払わなければなりませんでしたが、耕作がすでに終了した場合、自分でそれを収穫し、作物から借金を支払わなければなりません。耕作者が作物を得なかった場合、これは彼の契約をキャンセルしません。誓約は、記事の本質的な価値が負債の額に等しい場合にしばしば行われました。しかし、誓約の利益が借金の利息に対する相殺である場合、解毒防止の誓約がより一般的でした。債務者の財産全体が、債務者が享受できるようになることなく、債務の支払いの保証として誓約される可能性があります。債務者が返済するか、保証人が自ら責任を負うという個人的な保証がしばしば与えられました。 "<^>

紀元前2000年のメソポタミアからの売買契約

不動産の売買契約、シュメール、c。 2000 BC」「これは、シュメールの歴史の最後の時代からの取引です。それは、それについての現代のビジネス方法の風味を持つ転送とタイトルの形式を示します。「Sil-Ishtar、Ilu-eribuの息子、およびApil-彼の兄弟であるイリは、Sini-Ishtarの家、そして次にMinaniの家の隣に、Sini-Ishtarの家の隣に、Sini-Ishtarの家の隣にある耕地の3分の1のSharを建設しました。通り; Migrat-Sinの息子であるMinaniからのMinaniの財産、Migrat-Sinの息子。彼らは銀の4半シェケルを支払いました、価格は同意しました。ミナニの家。彼らは王によって誓った。(14人の証人と書記官の名前が続く。)月テベ、カラシャマシュの万里の長城の年。 [出典:ジョージアーロンバートン、「契約」、アッシリアおよびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、ロバートフランシスハーパー(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904年)による重要な紹介、pp。256-276、インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミア]

販売契約

立っている作物の販売契約、サイラスの7年、紀元前532年。この契約は、レンタルと土地の販売の中間クラスに属します。どちらかではなく、立った作物が販売されます。」リウ・ベルの路地にある耕作地から、エギビの息子であるナブ・アキ・イディンの息子であるイッティ・マルドゥク・バラトゥは、シュズブの娘タシミトゥム・ダムカットから購入しました。 、シグアの息子、ナディン・アプル、エピシュ・イルの息子、リムットの息子。 Itti-Marduk-balatuは、国の王であるバビロンの王であるキュロスの7年目のその畑の作物の価格を、タシミトゥムダムカットとナディンアプルの手に数えました。 (その後、2人の証人と書記官の名前が続きます)キュロスの7年目、ウルルの13番目のバビロン。

ダリウスの32年、紀元前490年の日付の売買契約は、この取引の場所であるシブツはバビロンの郊外でした。これは、女性、特に下層階級の女性がどのようにビジネスを続けたかを示しています。 Aqubatumの名前であるAradya [「私の奴隷」]が示すように、奴隷でした。「Tanishaの娘Nukaibuの娘と_______の娘Khamazaから女性Aqubatumへのデートの1つの才能、アラディアの娘、シマン月に1才1才の才能を発揮しますシャマシュ・ジル・エピッシュ、シャマシュ・マルクの息子、シブトゥ、バダルの王ダリウスの6年、32年、そして国々 」

小麦の販売契約、ダリウスの30年、紀元前487年。」このタブレットは良い

、、、

食料品の単純な取引の図解。これには多くのものがあり、そのうちの1つまたは2つの追加例を以下に示します。農民は通常、この文書のように、収穫のはるか前に農産物の販売を請け負いました。この例では、穀物が熟して配達される6ヶ月前に販売が行われました。 Nabu-napshat-su-zizの息子Shamash-malkuからRimutの息子Shamash-iddinまでの6つの才能の小麦。月に、小麦のシマン、全6タレント、彼はシャブマシ・イディンの家で、シブツで配達します。目撃者:ナブ・ウスル・ナピシュティの息子、シャマシュ・イディン。シン・アキ・イディンの息子、アブ・ヌ・エムク。シン・イディンの息子シャルル・ベル。マルラの息子、アバン・ニミク・ルクス。スクライブ、アラディヤ、エピッシュ・ジルの息子。シブツ、キリムの11日、ダリウスの国王の35年。

紀元前2000年のメソポタミアからの賃貸契約

賃貸住宅の契約、1年の期間、c。 2000 B.C. "これは最もシンプルなレンタル形態であり、バビロニア時代の初期からのものです。" Akhibteは、所有者のMashquからMashquの家を1年間リースしました。彼は銀の1シェケル、1年分の家賃を支払います。タムズの5日目に彼は占領します。 (その後、4人の証人の名前に従います。)Kar-Shamashの壁の年であるTammuzの5番目の日付。 "[出典:ジョージアーロンバートン、「契約」、アッシリアおよびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、批判的ロバートフランシスハーパーによる紹介(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904)、pp。256-276、インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミア]

財産契約の分割

家の賃借と修理の契約、1年間、ダリウスの35年、紀元前487年」この契約は最も興味深いものです。イシュフヤは明らかにシャマシュ・イディンの入居者であり、彼が住んでいる家の修理を請け負っています。彼はその年の家賃に加えて、仕事の開始時と完了時に2回の支払いで15シェケルのお金を受け取ることになっています。最後の支払いはBelの日に行われます。契約が行われた1週間後のテベットの最初のもので、その後修理が完了しなかった場合、イスキュヤは4シェケルを失うことになりました。

「今年は、リムットの息子であるシャマシュ・イディンの家の家賃に加えて、現金で15シェケル(現金)、アシシュの司祭の息子であるシャカ・ベルの息子であるイスカに行きます。支払いのため、彼は(家の)弱点を修復し、壁のひびを閉じます。彼は最初にお金の一部を、完了時にお金の一部を支払うものとします。彼はそれを嘆き悲しむ日、ベルの日に支払わなければならない。テベトの最初の日の後、イスキュヤによって家が完成しなかった場合、シャマシュ・イディンは現金で4シェケルのお金を彼の手で受け取る。イスキュヤ。 (その後、3人の証人と書記官の名前が続きます。)日付は、ダリウスの35年目であるキスリムの21番目のシブツにあります。

不動産の賃貸借契約、60年、Artaxerxesの36年、紀元前428年」この複雑な契約は、リースが非常に長い期間にわたるため、異常な関心事です。家賃は前払いされ、借手は「ミトラダトゥの息子バガミリは、ムラシュの息子であるベルシュム・イディンに自分の自由意志について語り、「私は自分の耕作地と未開拓地を賃貸し、シンの運河の土手とシリクティ運河の土手にある父の亡き兄弟ルシュンダティの耕作地と未耕作地、および北部のガリヤの町の住居Ninib-iddinの息子であるNabu-akhi-iddinの出身で、Nippurの市民であるBanani-erishの畑に隣接している。南では、バラトゥの息子、ミヌ・ベル・ダナの畑に隣接しています。東の罪の運河の土手。西には、シリクティの運河のほとり、そしてアルタレムの監督であるルシュンダティの畑に隣接しています。耕作地の家賃は、20タラントの日付になります。その後、ムラシュの息子であるベル・シュム・イディンは、耕作地と未耕作地、彼の叔父であるルシュンダーティの一部、および故人を参照して、彼の申し出を受け入れました。 ;彼は、年間20タレントのレンタルのために、その栽培部分を60年間保持し、植えるために未栽培部分を保持するものとします。毎年、バガミリのベルシュムイディンティシュリは、20才を与えます。ミトラダトゥの息子であるバガミリは、ムラシュの息子であるベル・シュム・イディンの手から60年間にわたって彼の畑の全家賃を受け取っていました。バガミリはその分野をベルシャムイディンから奪い、バガミリは銀のタレントをベルシャムイディンに1回支払う

es。買い手と売り手または任意の2つの契約当事者に対する保護として、証人の立ち会いのもとで書面による契約が必要であることが規定されています。契約が見つからない限り、請求を行うことはできません。また、請求があった場合に証人を提出できなかったことが、不正行為の試みの証拠であると仮定しています。興味深い事例は一連のパラグラフで言及されており、彼が自分に属する記事を失ったと主張する人が別の所持品で見つけたが、後者は彼が購入したと主張している。 [出典:Morris Jastrow、彼の著書「バビロニアとアッシリアにおける宗教的信仰と実践の側面」を出版してから10年以上後の講義1911 <>]

「ポイントは、有罪者を見つけることです。購入者はベンダーと販売の証人を法廷に持ち込まなければならず、財産を主張する者は主張を証明するために証人を連れて来なければなりません。両方の目撃者が現れ、彼らの証言が真実であることが示された場合、失われたと判断された財産の売り手は泥棒として明らかにされ、殺害されます。詐欺の悪化要因が盗難に加えられるため、このより厳しい罰が与えられます。記事は合法的な所有者に復元され、罪のない購入者は泥棒や詐欺業者の財産から補償されます。購入者がベンダーと販売証人の生産に失敗し、請求者が自分の財産を証明する証人を連れてくる場合、購入者は本物の泥棒として死に至り、盗まれた物品は合法的な所有者に戻されます。一方、申立人が自分の財産を証明する証人を連れて来ることができない場合、彼は不正請求をしたとみなされ、死刑に処せられます。その間にベンダーがそのようになったことが判明した場合でも、その金額はベンダーの不動産から購入者に復元されます。最後に、法律は、証人が一度にアクセスできない場合に、証人を作成するために6か月の期間を許可しています。 <>

「規範を規定する倫理原則に従って、銀行の取締役は、銀行の業務取引を通じて生じた損失について預金者に責任を負います。債権者の専制に対するビジネス取引における債務者の保護は、ほとんど極端に行われます。債権者は、裁判所の権限を取得せずに彼の債務者の財産を添付することはできないようです。で、もし。 e。 g。、彼は債務者の許可なしに債務者の穀倉地帯から自分自身を助けました、彼は借金の額を超えて取っていないかもしれませんが、彼は取ったものを返さなければならず、彼の意図的な行為によって元の主張を失います。裁判所は、耕作やその他の目的での牛のレンタル、整備士と労働者の賃金、貨物用の船のレンタル、畑の耕作のための返還額、さらには手術のための外科医の手数料さえも規制しました。強要と支払い不足の両方に対する保護を提供する見方。

ハンムラビ法典:100-112:商人と居酒屋と宿屋

バビロニア王ハンムラビ(紀元前1792-1750年)は、現存する最古の一連の法律であるハンムラビ法典を作成したとされています。目の正義のための目を文書化することで認められており、その深さと慎重さのために注目に値する、それは法的手続きと罰則を持つ282の判例法で構成されています。法律の多くは、それらを支える8フィートの高さの黒い閃緑岩にコードがエッチングされる前に存在していました。ハンムラビは、それらを一定の標準化された一連の法律に成文化しました。 [出典:L. W.キング訳]

100。 。 。お金の利子は、彼が受け取った限り、彼はそのためにメモをし、彼らが落ち着いた日に商人に支払います。

101.彼が行った場所に商業的な取り決めがない場合、彼はブローカーで受け取った全額を残して商人に与えるものとする。

102.商人が投資のためにエージェント(ブローカー)にお金を預け、ブローカーが行った場所で損失を被った場合、商人に資本を提供します。

103.旅中に敵が彼が持っていたものを彼から奪った場合、ブローカーは神に誓い義務を負わないものとする。

104.商人がトウモロコシ、羊毛、油、または輸送する他の商品を代理人に渡す場合、代理人はその金額の領収書を発行し、商人に補償するものとします。それから彼は、彼が商人に与えたお金のために商人から領収書を取得しなければならない。

105.エージェントが不注意であり、商人に与えたお金の領収書を受け取らない場合、彼は未収金を自分のものと見なすことはできません。

106.代理店が商人からお金を受け取るが、商人と口論をしている場合(領収書を拒否)、商人は神の前で誓い、このお金を代理人に渡したことを目撃し、代理人は彼に3合計。

107.商人がエージェントをだましている場合、後者が彼に戻ってきたので

ー

彼がそれと彼が植えた果樹園で行った仕事。その分野に対して請求が発生した場合、Baga'miriはそれを解決し、Bel-shum-iddinの代わりに支払います。アルタクセルクセスの第三十七年のニサンは、使用と植栽のための王であり、ムラシュの息子であるベル・シュム・イディンが六十年間所有する。 (30人の証人と書記官の名前が続き、そのうち11人はタブレットの端に印章の印象を残しました。L。34は、バガミリのサムネイルのプリントがタブレットに置かれたと述べています)彼のシールの。 (L. 37には、その情報が含まれています)このタブレットは、バガミリの母であるベルバラトゥイタンヌの娘であるエクルベリトの前で書かれました。 (日付は)Nippur、Tishri 2番目、Artaxerxesの36年目です。」

紀元前2000年のメソポタミアからの共同パートナーシップ契約

パートナーが収穫に対してお金を借りる契約c。紀元前2000年作物でお金を借りている2人の農民はパートナーです。ウラマシャの息子シン・カラマ・イディとカヤムディドゥの息子アピル・シュは、収穫の獲得のために16シェケルのお金をアラド・シンから借りています。 。 Abのお祭りでは、彼らは小麦を支払うでしょう。 (3人の証人と書記官の名前が続き、タブレットは特定の洪水の年に日付が付けられます。それが書かれた王の治世には記載されていませんが、それは明らかにウル3世の王朝または[出典:ジョージアーロンバートン、「契約」、アッシリアおよびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、ロバートフランシスハーパーによる重要な紹介(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904)、256-276ページ、インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミア]

奴隷購入の代理契約

パートナーシップの契約、ネブカデネザル2世の36年、紀元前568年」「ナブ・アキ・イディンは投資家だった。偉大なエギビ家の一員だった。彼はこの企業に4マナの資本を寄付した。 、彼は事業を遂行することになっていたが、彼が持っている財産や時間に関係なく、半分のマナと7シェケルを寄付した。シュラの息子、エギビの息子、ナブ・アヒ・イディンに属するお金と、シン・エムクの息子、ベル・アヒ・イディンの息子、ベル・シュヌに属する半分のマナ7シェケル、相互の協力関係。ベルシュヌが町や国に残っているものは何でも共通の財産となります。ベルシュヌが4シェケルを超える費用に費やすものは贅沢とみなされます。男性と筆記者であり、日付は36)のAbの最初のバビロンネブカドネザルの年。」

ネブカドネザル2世、紀元前564年、パートナーシップの契約」この文書から、イディン・マルドゥクとナブ・ウキンがネブカドネザルの40年目のテベットで協力関係を結んだことがわかります。その日から各パートナーが描きました翌年のウルル月には、さまざまな特定の目的のために多数の少量がIddin-Mardukに配達され、おそらく会社の義務の支払いとして、より多くの金額が他の2人の男性に支払われました。

「バディンの王ネブカドネザルの四十年目のテベトから、四十二年のマルケスワン月までの、イディン・マルドゥクとナブ・ウキンの株の覚書。 Iddin-Mardukの3分の1のマナは、41年目のテベットの月に彼の口座に引き出しました。お金の3分の1マナは、41年目のテベットの月に彼の口座に引き出しました。シェルから分割されたナブウキンのお金の15シェケルは、______から、42年目のウルルの15日にリムニヤの家のためにイディンマルドゥクに与えられました。貨幣の4番目のシェケルは、同じ手に渡されたヌートゥスキン用でした。パリピ・ナスカプに半シェケルのお金が与えられました。お金の1シェケルの3分の1が牛肉と同じ手に渡されました。肉に2ギリのお金が与えられました。 Lisi-nuriに1シェケルのお金が与えられました。カリアのための2シェケルのお金が同じ手に渡されました。 _____市、Markheswan ______。 1マナ50シェケルは、リシルとブニーニエピッシュの所有に数えられます。」

ビジネスを保護する法律

Morris Jastrowは次のように述べています。「商法の商業規則については、その根底にある基本原則は、それが属する責任の固定であり、取引の双方を詐欺からだけでなく不測の事態からも保護することです。 。法律の多くは一方の当事者の故意の詐欺または詐欺の場合を扱っていますが、一般的な仮定は、両方の当事者が正直な動機によって作動することであり、多くの場合、ビジネス活動の複雑さの増大

ーー

広告は彼に与えられましたが、商人は彼に返されたものの受け取りを拒否し、このエージェントは神と裁判官の前で商人に有罪判決を下し、エージェントが彼に与えたものの受け取りを拒否した場合は合計額の6倍を支払うものとしますエージェントに。

108.居酒屋の飼い主(女性)が飲み物の総重量に応じてトウモロコシを受け入れないが、お金がかかり、飲み物の価格がトウモロコシの価格よりも低い場合、彼女は有罪判決を受け、水に投げ込まれる。

109.共謀者が居酒屋の番人の家で会い、これらの共謀者が捕らえられて裁判所に引き渡されない場合、居酒屋の番人は殺害される。

110.「神の姉妹」が居酒屋を開くか、または酒場に入ろうとすると、この女性は焼死する。

111.旅館の管理人が60のkaにうさかにドリンクを提供する場合。 。 。彼女は収穫時に50 kaのトウモロコシを受け取る。

112.誰かが旅に出て、銀、金、宝石、または他の動産を他の人に委託し、彼からそれを取り戻したい場合。後者がすべての財産を指定された場所に運ばないが、自分の使用に適切な場合、財産を引き渡さなかったこの男性は有罪判決を受け、そのすべてに対して5倍を支払うものとします彼に託されていた。

シュメールのバランスシート

ハンムラビ法典:113-126:債権と債務

113.誰かがトウモロコシまたはお金の委託を受けており、所有者の知らないうちに穀倉または箱から持ち出した場合、所有者の知らないうちにトウモロコシを穀倉または箱から出した人は法的に有罪判決を受け、彼がとったトウモロコシを返済します。そして、彼は彼に支払われた手数料、または彼のために支払われたものを失います。 [出典:L. W.キング訳]

114.人がトウモロコシと金を他の人に要求せず、それを強制的に要求しようとする場合、すべての場合に銀の3分の1を支払う。

115.誰かが他の人にトウモロコシまたは金銭の請求をして、彼を投獄する場合;囚人が刑務所内で自然死した場合、訴訟はそれ以上進行しない。

116.囚人が一撃または虐待により刑務所で死亡した場合、囚人の主人は裁判官の前で商人に有罪判決を下すものとする。もし彼が自由に生まれた男であったなら、商人の息子は死刑に処される。それが奴隷であった場合、彼は金のミナの3分の1を支払い、囚人の主人が与えたすべては没収します。

117.誰かが借金の請求に応じず、自分自身、妻、息子、娘を金銭で売ったり、強制労働に渡したりしない場合、彼らはそれらを買った男の家で3年間働く、または所有者、および4年目には解放されます。

118.強制労働のために男性または女性の奴隷を渡し、商人が奴隷を転貸したり、お金で売ったりした場合、異議を唱えることはできません。

119.誰かが借金の請求に応じず、子供を産んだメイドの使用人を金で売った場合、商人が支払った金は奴隷の所有者から彼に返還され、彼女は解放されました。

120.誰かが他の人の家に安全に保管するためにトウモロコシを保管し、保管中のトウモロコシに害が発生した場合、家の所有者が穀倉を開けてトウモロコシの一部を摂取した場合、または特にトウモロコシを拒否した場合トウモロコシの所有者は彼のトウモロコシを神の前で(宣誓で)主張し、家の所有者は彼が取ったすべてのトウモロコシの所有者に支払います。

121.ある人が別の人の家にとうもろこしを保管する場合、彼は1年に5 KAコーンごとに1グルの割合で彼に保管を支払うものとします。

122.誰かが別の銀、金、または他のものを保管する場合、彼は証人にすべてを見せ、契約書を作成し、それを安全な保管のために引き渡します。

123.彼が証人または契約なしに安全に保管するために引き渡し、それを与えられた人がそれを拒否した場合、彼は正当な主張を持たない。

124.証人の前で、誰かが安全に保管するために他の人に銀、金、または他のものを配達するが、彼がそれを否定する場合、彼は裁判官の前に連れて行かれ、彼が拒否したすべてを全額支払うものとする。

125.誰かが自分の財産を安全に保管するために他の人と置き、そこで泥棒または強盗を通して、彼の財産と他の男性の財産が失われた場合、損失を無視した家の所有者は、担当者に与えられたすべてのことを所有者に補償します。しかし、家の所有者は、自分の財産を追跡して回収し、泥棒からそれを奪おうとします。

126.商品を紛失していない人が紛失したと述べ、虚偽の主張をした場合:もし彼が自分の商品と怪我の額を神の前で主張した場合、彼はそれらを紛失していなくても、完全に補償されます彼の損失は主張した。 (つまり、必要なのは誓いだけです。)

紀元前611年のメソポタミアからのローンと住宅ローンの契約

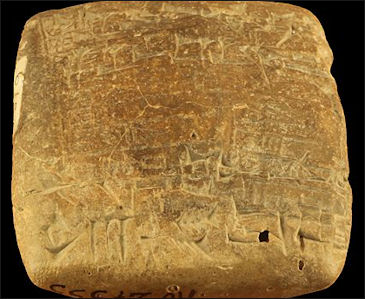

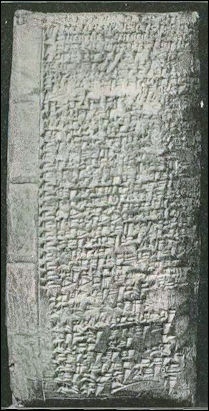

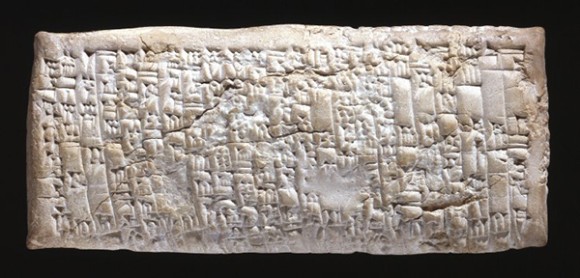

紀元前2000年頃のUrのアカウントを持つタブレット

マネーローンの契約、ナボポラッサルの14年、紀元前611年これはモールです

ローンのセキュリティで不動産のtgage。利子は11パーセントと3分の1の割合でした。「1マナのお金、Kalab-Sinの息子Iqisha-Mardukに属する金額、(貸与)は_____の息子、_____の息子、 _____。毎年、マナの量はその合計を7シェケルのお金で増加させます。ベルの門の近くにある彼の畑は、イキシャ・マルドゥクの誓約です。 (この文書は4人の証人の名前を持ち、日付が付けられています)ナボポラッサル(ネブカドネザルの父)の14年目に、タムズの27番目のバビロンで(ネブカドネザルの父)。[出典:アッシリアの「契約書」およびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、ロバートフランシスハーパーによる重要な紹介(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904)、pp。256-276、インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミア]

お金の貸付けの契約、ネブカドネザル2世の6年目、紀元前598年」この場合の利子率は13パーセントと3分の1パーセントでした。「1マナのお金、アプラの息子ダン・マルドゥクの息子ダガーを身に着けている者の(貸与)エギビの息子イクシャ・アプラの息子クドゥルに。毎年マナの量は、その合計額を8シェケルのお金で増やさなければならない。ダン・マルドゥックに誓約されているかもしれない。(日付は)ネダルカドネザルの6年目のアダル4世バビロン。

融資の契約、ナボニドスの5年目、紀元前550年この融資は、ナボニドゥスの5年目に、3番目に行われました。債権者には担保は与えられなかったが、彼は20パーセントの利子を受け取った。「イディン・アプルの息子、ヌル・シンの息子であるイディン・マルドゥクに属する1.5マナのお金、アディヤとブナニット、彼の妻の息子、ハダド・ナタン。毎月、マナの量は、その金額を1シェケル分増やします。彼らはバビロンの王ナボニドスの五年目の月の初めから、その金額を支払う。呼び出しは、Ibaに属する家で利息のために行われます。毎月、合計が支払われます。」

紀元前560年のメソポタミアからの破産契約

住宅ローンの購入契約、悪のメロダッハ2年、紀元前560年それは、破産の場合に、債権者の利益が抵当財産の売却でどのように保存されたかを示しています。また、バビロニアの法律では、財産の価値が債権者に犠牲にされたのではなく、債務者が実際に彼に属している財産の持分を取得できることを証明しています。 [出典:ジョージアーロンバートン、「契約」、アッシリアおよびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、ロバートフランシスハーパー(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904年)による重要な紹介、pp。256-276、インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミア]

お金のマナの3分の2、鍛冶屋の息子シャピクジルの息子であるベルジルエピッシュから、ジンへのローンである_____の息子であるバラツの息子であるナブアプライディンへの融資(土地の)債権者に届けられ、(上で)Nabu-apla-iddinの家、(その)Bel-shum-ishkunの息子、Nergal-sharra-usurはお金のために買った。支払いのための3分の1マナのお金。債権者に、スミスの息子であるBel-zir-epishの息子であるMarduk-apla-iddinがNabu-akhi-からNergal-sharra-usurの代理人として受け取った。エジンビの息子、シュラの息子、イドディン。 3分の2のマナ(これは、ベルジルエピッシュ(貸与))が、息子のNergal-Sharra-usurに贈ったNabu-apla-iddin、Marduk-apla-usurの領収書。王の書記官にマルドゥク・アプラ・ウスールが語り、所有の印章を受け取るまで、ベル・シュクタヌの息子、ナブ・シュム・イディンの息子、ナブ・アキ・イディンは領収書の証明書を保持する。お金の3分の2のマナ。 (この楽器の日付は)邪悪なメロダッハの二年目の二十六日、ニサンのバビロン。

住宅ローンの契約購入、ネリグリサールの初年度、紀元前559年、イッサーの加入年。場所はバビロンです。それを書いた筆記者、イキシャ・アプリの息子。邪悪なメロダッハの治世の時代に書かれたタブレットが2人によって保持されたNabu-apla-iddinの家の住宅ローンは、Iqisha-aplaの手に移されていました。現在の取引から、住宅ローンの半分が返済されたようです。どうやら残りの半分は支払えず、家は売却されたようです。この場合、購入者は王、ネリグリサールでしたが、彼は最近王位に就きました。他の多くのリーガル購入者と同様に、彼は資金不足であり、Egibi会社の長からお金を借りざるを得なかった。王は、26分の1シェケル(未払いのままのローンの半分)を家に持ち込み、住宅ローンの所有者に銀行への引き渡しを強要したようです。この場合、正しかった可能性があり、公平性は失われました。 [ソース:ジョージアーロンバートン、「契約」、アッシリアおよびバビロニア文学:選択されたトランザクション、ロバートフランシスハーパーによる重要な紹介(ニューヨーク:D.アップルトン&カンパニー、1904)、pp。256-

「金の52半シェケルは、ギルアの息子、シンシャドゥヌの息子であるイキシャアプラに属しており、______の息子であるバラトゥの息子であるナブアプライディンから受け取った。宮殿の現金のために購入したNabu-apla-iddinの家。残りの残高、26/4シェケルのお金、シン・シャドゥヌの息子、ギルアの息子、イクシャ・アプラは、エギビの息子、シュラの息子、ナブ・アキ・イディンの手から受け取りました。 Nabu-apla-iddinからNabu-akhi-iddinへの52シェケルの領収書が与えられました。」

継承と負債に関するアッシリアの法典(紀元前1075年頃)

紀元前2000年頃のウルの商人の商品のタブレット

I.26。女性が父親の家に住んでいて、夫が亡くなった場合、夫が彼女に決めた贈り物---もし夫の息子がいたら、それを受け取る。夫の息子がいない場合、彼女はそれを受け取ります。 [出典:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook]

I.32。女性が父親の家に住んでいるが、夫の家に連れて行かれたかどうかにかかわらず、夫に与えられた場合、夫のすべての借金、軽罪、犯罪それらをコミットしました。同様に、彼女が夫と一緒に住んでいる場合、彼のすべての犯罪も同様に負わなければならない。

I.35。未亡人である女性が男性の家に入れば、彼女が持参するものは何でも---すべては夫のものです。しかし、男性が女性に入る場合、彼がもたらすものは何でも---すべてが女性のものです。

I.37。男性が妻と離婚した場合、望むなら、彼は彼女に何かを与えるかもしれません。彼が望んでいなければ、彼は彼女に何も与える必要はありません。彼女は外に出なければならない。

I.46。夫の死により夫が亡くなった女性が家から出て行かない場合、夫が何も残さなかった場合、彼女は息子の一人の家に住まわなければならない。夫の息子たちは彼女を支えなければならない。彼女の食べ物と飲み物、彼らが求愛している婚約者については、彼女は彼女を提供することに同意しなければならない。彼女が二人目の妻であり、自分の息子がいない場合、夫の息子の一人と一緒に住み、グループは彼女を支援します。彼女が自分の息子を持っている場合、彼女自身の息子が彼女をサポートし、彼女は彼らの仕事をしなければならない。しかし、夫の息子の中に彼女と結婚する人がいる場合、他の息子は彼女を支持する必要はありません。

II.2。父方の財産をまだ分割していない兄弟の中で男が殺人を犯した場合、彼らは血の復to者に彼を与えなければならない。彼が選択した場合、彼はspareしまないかもしれません。彼がつかむかもしれない父方の財産の彼の部分。

II.6。彼が銀のために野原または家をとる前に、1日に1回3回、バイヤーはアシュール市で宣言を行い、3回彼は彼が野原と家を買う都市で宣言をしなければならない。したがって、「私が購入しているこの都市の耕作可能地域にある、まあまあの息子のフィールドと家。所有している、または異議がない、または所有権を主張しているようなもの、タブレットを持ってきて、治安判事の前に横たえさせて、主張を示し、称号を証明させ、自分のものを奪わせてください。 、判事の前に彼らを置き、彼に属するものを完全に受け取ります。」バイヤーが宣言をした場合、彼らはタブレットを書き、治安判事は彼に彼に与えます:「今月の日に、バイヤーは3回宣言をしました。私にとって、彼らを私の前に置いたのではなく、野原と家で分かち合うという彼の主張を没収しなければならない。宣言をする人、つまり買い手にとっては、無料です。」

II.8。男が隣人の野原に干渉した場合、彼らは彼を有罪とする。彼は三倍に回復しなければならない。彼の指の片方が切れ、百打撃で彼に与えられ、彼は王の働きをする一ヶ月の日を過ごす。

III.2。借金のために家に住んでいた人の息子または娘を売る人は、有罪判決を受け、金を失う。そして彼は未成年の息子を財産の所有者に渡すものとする。百のまつげは彼に与え、二十日は王の働きをする。

画像ソース:ウィキメディアコモンズ

テキストソース:インターネット古代史ソースブック:メソポタミアsourcebooks.fordham.edu、ナショナルジオグラフィック、スミソニアンマガジン、特にMerle Severy、ナショナルジオグラフィック、1991年5月、マリオンスタインマン、スミソニアン、1988年12月、ニューヨークタイムズ、ワシントンポスト、ロサンゼルスタイムズ、雑誌、タイムズオブロンドン、自然史誌、考古学雑誌、ニューヨーカー、BBC、百科事典ブリタニカ、メトロポリタン美術館、時間、ニューズウィーク、ウィキペディア、ロイター、AP通信、ガーディアン、AFP、ロンリープラネットガイド、世界宗教ジェフリー・パーリンダー編集(ファクト・オン・ファイル・パブリケーションズ、ニューヨーク);ジョン・キーガンによる戦争の歴史(ビンテージ・ブックス)。美術史

276、インターネット古代史のソースブック:メソポタミア]

H.W. ヤンソンプレンティスホール、イングルウッドクリフス、ニュージャージー州)、コンプトン百科事典、およびさまざまな書籍やその他の出版物。

最終更新日:2018年9月

★★

Accounting clay envelopeMesopotamia was the first place where crop surpluses were produced to such a degree that enough labor was freed that it could be harnessed to build cities and monuments, produce art and crafts and support merchants, temples and monarchs.

Accounting clay envelopeMesopotamia was the first place where crop surpluses were produced to such a degree that enough labor was freed that it could be harnessed to build cities and monuments, produce art and crafts and support merchants, temples and monarchs.

The Sumerian used the world's first writing to record economic transactions and participate in a trade network that extended over thousands of miles. The Babylonians are credited with expanding commerce and developing an early banking system.

Most of the early writing was used to make lists of commodities. The writing system is believed to have developed in response to an increasingly complex society in which records needed to be kept on taxes, rations, agricultural products and tributes to keep society running smoothly.

The oldest examples of Sumerian writing were bills of sales that recorded transactions between a buyer and seller. When a trader sold ten head of cattle he included a clay tablet that had a symbol for the number ten and a pictograph symbol of cattle.

The Mesopotamians could also be described as the worlds first great accountants. They recorded everything that was consumed in the temples on clay tablets and placed them in the temple archives. Many of the tablets recovered were lists of items like this. Royal seals were affixed to products.

See Trade

Book: Snell, Daniel C., Ledgers and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

Categories with related articles in this website: Mesopotamian History and Religion (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Mesopotamian Culture and Life (38 articles) factsanddetails.com; First Villages, Early Agriculture and Bronze, Copper and Late Stone Age Humans (50 articles) factsanddetails.com Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Mesopotamia: Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; Mesopotamia University of Chicago site mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu; British Museum mesopotamia.co.uk ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Louvre louvre.fr/llv/oeuvres/detail_periode.jsp ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology penn.museum/sites/iraq ; Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago uchicago.edu/museum/highlights/meso ; Iraq Museum Databaseoi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/dbfiles/Iraqdatabasehome ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Oriental Institute Virtual Museum oi.uchicago.edu/virtualtour ; Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur oi.uchicago.edu/museum-exhibits ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org

Archaeology News and Resources: Anthropology.net anthropology.net : serves the online community interested in anthropology and archaeology; archaeologica.org archaeologica.org is good source for archaeological news and information. Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com features educational resources, original material on many archaeological subjects and has information on archaeological events, study tours, field trips and archaeological courses, links to web sites and articles; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org has archaeology news and articles and is a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America; Archaeology News Network archaeologynewsnetwork is a non-profit, online open access, pro- community news website on archaeology; British Archaeology magazine british-archaeology-magazine is an excellent source published by the Council for British Archaeology; Current Archaeology magazine archaeology.co.uk is produced by the UK's leading archaeology magazine; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com is an online heritage and archaeology magazine, highlighting the latest news and new discoveries; Livescience livescience.com/ : general science website with plenty of archaeological content and news. Past Horizons : online magazine site covering archaeology and heritage news as well as news on other science fields; The Archaeology Channel archaeologychannel.org explores archaeology and cultural heritage through streaming media; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu : is put out by a non-profit organization and includes articles on pre-history; Best of History Websites besthistorysites.net is a good source for links to other sites; Essential Humanities essential-humanities.net: provides information on History and Art History, including sections Prehistory

Industry, Resources and Business in Mesopotamia

Economic tablet from SusaOrganized production of handcrafted good was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

Economic tablet from SusaOrganized production of handcrafted good was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

The Sumerians a developed sense of ownership and private property. It seems like many business transactions were recorded and the minutest amounts and smallest quantities were listed. Contracts were sealed with cylinder seals that were rolled over clay to produce a relief image.

There wasn't much in Ur and other cities in Mesopotamia except water from the Euphrates River and mud brick made from the dry earth. Prized materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian all were imported.

See Naptu, Oil

Herodotus on Babylonian Economic Activity

Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C."“Among many proofs which I shall bring forward of the power and resources of the Babylonians, the following is of special account. The whole country under the dominion of the Persians, besides paying a fixed tribute, is parceled out into divisions, which have to supply food to the Great King and his army during different portions of the year. Now out of the twelve months which go to a year, the district of Babylon furnishes food during four, the other of Asia during eight; by the which it appears that Assyria, in respect of resources, is one-third of the whole of Asia. Of all the Persian governments, or satrapies as they are called by the natives, this is by far the best. When Tritantaechmes, son of Artabazus, held it of the king, it brought him in an artaba of silver every day. The artaba is a Persian measure, and holds three choenixes more than the medimnus of the Athenians. He also had, belonging to his own private stud, besides war horses, eight hundred stallions and sixteen thousand mares, twenty to each stallion. Besides which he kept so great a number of Indian hounds, that four large villages of the plain were exempted from all other charges on condition of finding them in food. I.193: But little rain falls in Assyria, enough, however, to make the corn begin to sprout, after which the plant is nourished and the ears formed by means of irrigation from the river. For the river does not, as in Egypt, overflow the corn-lands of its own accord, but is spread over them by the hand, or by the help of engines. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

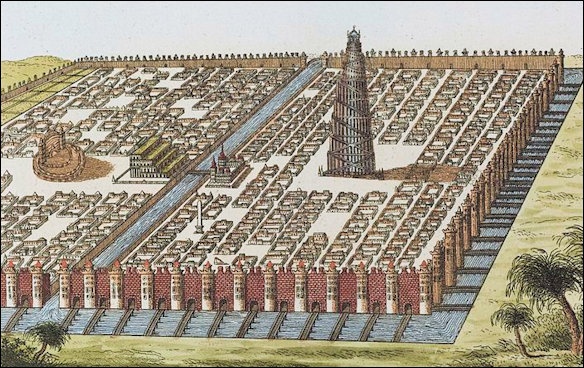

“The whole of Babylonia is, like Egypt, intersected with canals. The largest of them all, which runs towards the winter sun, and is impassable except in boats, is carried from the Euphrates into another stream, called the Tigris, the river upon which the town of Nineveh formerly stood. Of all the countries that we know there is none which is so fruitful in grain. It makes no pretension indeed of growing the fig, the olive, the vine, or any other tree of the kind; but in grain it is so fruitful as to yield commonly two-hundred-fold, and when the production is the greatest, even three-hundred-fold. The blade of the wheat-plant and barley-plant is often four fingers in breadth. As for the millet and the sesame, I shall not say to what height they grow, though within my own knowledge; for I am not ignorant that what I have already written concerning the fruitfulness of Babylonia must seem incredible to those who have never visited the country. The only oil they use is made from the sesame-plant. Palm-trees grow in great numbers over the whole of the flat country, mostly of the kind which bears fruit, and this fruit supplies them with bread, wine, and honey. They are cultivated like the fig-tree in all respects, among others in this. The natives tie the fruit of the male-palms, as they are called by the Hellenes, to the branches of the date-bearing palm, to let the gall-fly enter the dates and ripen them, and to prevent the fruit from falling off. The male-palms, like the wild fig-trees, have usually the gall-fly in their fruit. I.194:

Babylon

“But that which surprises me most in the land, after the city itself, I will now proceed to mention. The boats which come down the river to Babylon are circular, and made of skins. The frames, which are of willow, are cut in the country of the Armenians above Assyria, and on these, which serve for hulls, a covering of skins is stretched outside, and thus the boats are made, without either stem or stern, quite round like a shield. They are then entirely filled with straw, and their cargo is put on board, after which they are suffered to float down the stream. Their chief freight is wine, stored in casks made of the wood of the palm-tree. They are managed by two men who stand upright in them, each plying an oar, one pulling and the other pushing. The boats are of various sizes, some larger, some smaller; the biggest reach as high as five thousand talents' burthen. Each vessel has a live ass on board; those of larger size have more than one. When they reach Babylon, the cargo is landed and offered for sale; after which the men break up their boats, sell the straw and the frames, and loading their asses with the skins, set off on their way back to Armenia. The current is too strong to allow a boat to return upstream, for which reason they make their boats of skins rather than wood. On their return to Armenia they build fresh boats for the next voyage. I.195:

Money in Mesopotamia

Among the Sumerians economic units of measure were the 1) gur, a unit of volume roughly equal to 26 bushels; 2) kug or ku, silver or money; and 3) gin or gig, a small axe head used as money roughly equal to a shekel. John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: “From the Ur III period we have tablets from different places and times that give the silver equivalents of different quantities of different commodities.During the Ur III period, the state was the main creditor. The state supplied so much land or so many animals to the individual, who then had to pay the state back. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Silver rings were used in Mesopotamia and Egypt as currency about 2000 years before the first coins were struck. Some archaeologists suggest that money was used by wealthy citizens of Mesopotamia as early as 2,500 B.C., or perhaps a few hundred years earlier. Historian Marvin Powell of Northern Illinois in De Kalb told Discover, "Silver in Mesopotamia functions like our money today. It's a means of exchange. People use it for storage of wealth, and the use it for defining value."[Source: Heather Pringle, Discover, October 1998]

The difference between the silver rings used in Mesopotamia and earliest coins first produced in Lydia in Anatolia in the 7th century B.C. was that the Lydian coins had the stamp of the Lydian king and thus were guaranteed by an authoritative source to have a fixed value. Without the stamp of the king, people were reluctant to take the money at face value from a stranger.

Archaeologists have had a difficult time sorting out information on ancient money because, unlike pottery or utensils, found in abundant supply at archeological sites, they didn't thrown them out.

Development of Proto Money

Clay accounting tokensThe earliest form of trade was barter. The earliest known proto-money are clay token excavated from the floors of villages houses and city temples in the Near East. The tokens served as counters and perhaps as promissory notes used before writing was developed. The tokens came in different sizes and shapes.

Clay accounting tokensThe earliest form of trade was barter. The earliest known proto-money are clay token excavated from the floors of villages houses and city temples in the Near East. The tokens served as counters and perhaps as promissory notes used before writing was developed. The tokens came in different sizes and shapes.

Early Mesopotamians who lived in the Fertile Crescent before the rise of the first cities employed five token types that represented different amounts of the three main traded goods: grain, human labor and livestock such as goats and sheep.

Clay tokens, described by some scholars as the world's first money, found in Susa, Iran have been dated to 3300 B.C. One was equivalent to one sheep. Others represented a jar of oil, a measure of metal, a measure of honey, and different garments.

In the Mesopotamian cities, there were 16 main types of tokens and dozens of sub categories for things like honey, trussed duck, sheep's milk, rope, garments, bread, textiles, furniture, mats, beds, perfume and metals.

Development of Money Idea and the Idea Behind it

Thomas Wyrick, an economist at Southwestern Missouri State University told Discover, "If there were a thousand different goods being traded up and down the street, people could set the price in a thousand different ways because in a barter economy each good is priced in terms of other goods. So one pair of sandals equals ten dates, equals one quart of wheat, equals two quarts of bitumen, and so on."

"Which is the best price? It's so complex that people don't know if they are getting a good deal. For the first time in history, we've got a large number of goods. And for the first time, we have so many prices that it overwhelms the human mind. People needed some standard way of stating value."

In Mesopotamia, silver became the standard of value sometime between 3100 B.C. and 2500 B.C. along with barley. Silver was used because it was a prized decorative material, it was portable and the supply of it was relatively constant and predictable from year to year.

Sometime before 2500 B.C. a shekel of silver became the standard currency. Tablets listed the price of timber and grains in shekels of silver. A shekel was equal to about one third of an ounce, or little more than three pennies in terms of weight. One month of labor was worth 1 shekel. A liter of barely sold for 3/100ths of shekel. A slave sold for between 10 and 20 shekels.

No long after shekels appeared as a means of exchange, kings began levying fines in shekels as a punishment. Around 2000 B.C., in the city of Eshnunna, a man who bit another man's nose was fined 60 shekels. A man who slapped another man in the face had to pay up 20 shekels.

Ring Money in Mesopotamia

Receipt for clothesIn the early days of shekels, people carried pieces of metal in bags and amounts were measured out on scales with stones as countermeasures on the other side. Between 2800 B.C. and 2500 B.C., pieces of silver were caste a standard weight, usually in the form of rings or coils called har on tablets. These rings, worth between 1 and 60 shekels, were used primarily by the rich to make big purchases. They came in a number of different forms: large ones with triangular ridges, thin coils.

Receipt for clothesIn the early days of shekels, people carried pieces of metal in bags and amounts were measured out on scales with stones as countermeasures on the other side. Between 2800 B.C. and 2500 B.C., pieces of silver were caste a standard weight, usually in the form of rings or coils called har on tablets. These rings, worth between 1 and 60 shekels, were used primarily by the rich to make big purchases. They came in a number of different forms: large ones with triangular ridges, thin coils.

A 3,700-year-old tablet from the Euphrates River town of Sippar recorded a bill of sale of a woman who bought some land with a silver ring, worth the equivalent of 60 months wages for an ordinary worker, that she received from her parents.

To pay their bills ordinary people used less valuable money made of tin, copper or bronze. Barley was also used as currency. The advantage with it was that small weighing errors made little difference and it was difficult to cheat someone.

The use of money made trade easier between city-states and kingdoms and well as between Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine.

Problems with Money

The main problem with silver is that it was so valuable that weighing errors or impure silver should translate to a large amount of lost value. Some people tried to purposely cheat others by adding other metals into gold or silver or even substituting look-a-like metals.

Fraud and cheating were so prevalent in the ancient world that there are eight passages in the Old Testament that forbid tampering with scales or substituting lighter for heavier stones.

People often fell into debt---a conclusion based on numerous tablet letters describing people in various kinds of trouble for falling into debt. Many debtors became slaves. The situation got so out of hand in Babylon that King Hammurabi decreed that no one could be enslaved for more than three years for debt. Other cities, with residents racked by debt, issued moratoriums on all outstanding bills.

zavazi hematite

zavazi hematiteModern Banking Began in Ancient Babylonian Temples

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gold, silver and other valuables were deposited in temples for safe-keeping. The history of banks can be traced to ancient Babylonian temples in the early 2nd millennium B.C.. In Babylon at the time of Hammurabi, there are records of loans made by the priests of the temple. Temples took in donations and tax revenue and amassed great wealth. Then, they redistributed these goods to people in need such as widows, orphans, and the poor. [Source: MessageTo Eagle March 7, 2016 Ancient History Facts]

After a thousand years, the priests who ran the temples had so much money that the concept of banking came up as an idea. Around the time of Hammurabi, in the 18th century B.C., the priests allowed people to take loans. Old Babylonian temples made numerous loans to poor and entrepreneurs in need. Among many other things, the Code of Hammurabi recorded interest-bearing loans."

The text on a cuneiform tablet detailing a loan of silver, c. 1800 B.C., reads: “3 1/3 silver sigloi, at interest of 1/6 sigloi and 6 grains per sigloi, has Amurritum, servant of Ikun-pi-Istar, received on loan from Ilum-nasir. In the third month she shall pay the silver." 1 sigloi=8.3 grams.

The loans were made at reduced below-market interest rates, lower than those offered on loans given by private individuals, and sometimes arrangements were made for the creditor to make food donations to the temple instead of repaying interest. Cuneiform records of the house of Egibi of Babylonia describe the families financial activities dated as having occurred sometime after 1000 B.C. and ending sometime during the reign of Darius I, show a “lending house” a family engaging in “professional banking."

Property in Mesopotamia

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“The god of a city was originally owner of its land, which encircled it with an inner ring of irrigable arable land and an outer fringe of pasture, and the citizens were his tenants. The god and his viceregent, the king, had long ceased to disturb tenancy, and were content with fixed dues in naturalia, stock, money or service. One of the earliest monuments records the purchase by a king of a large estate for his son, paying a fair market price and adding a handsome honorarium to the many owners in costly garments, plate, and precious articles of furniture. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 <^>]

The Hammurbai Code “recognizes complete private ownership in land, but apparently extends the right to hold land to votaries, merchants (and resident aliens?). But all land was sold subject to its fixed charges. The king, however, could free land from these charges by charter, which was a frequent way of rewarding those who deserved well of the state. It is from these charters that we learn nearly all we know of the obligations that lay upon land. The state demanded men for the army and the corvee as well as dues in kind. <^>

“A definite area was bound to find a bowman together with his linked pikeman (who bore the shield for both) and to furnish them with supplies for the campaign. This area was termed "a bow" as early as the 8th century B.C., but the usage was much earlier. Later, a horseman was due from certain areas. A man was only bound to serve so many (six?) times, but the land had to find a man annually. The service was usually discharged by slaves and serfs, but the amelu (and perhaps the muskenu) went to war. The "bows" were grouped in tens and hundreds. The corvee was less regular. The letters of Hammurabi often deal with claims to exemption. Religious officials and shepherds in charge of flocks were exempt. Special liabilities lay upon riparian owners to repair canals, bridges, quays, etc.

Ownership of Property the Hammurabi Code

pre-Sumerian sale of a field

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: “The Code recognizes many ways of disposing of property--sale, lease, barter, gift, dedication, deposit, loan, pledge, all of which were matters of contract. Sale was the delivery of the purchase (in the case of real estate symbolized by a staff, a key, or deed of conveyance) in return for the purchase money, receipts being given for both. Credit, if given, was treated as a debt, and secured as a loan by the seller to be repaid by the buyer, fr which he gave a bond. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 <^>]

“The Code admits no claim unsubstantiated by documents or the oath of witnesses. A buyer had to convince himself of the seller's title. If he bought (or received on deposit) from a minor or a slave without power of attorney, he would be executed as a thief. If the goods were stolen and the rightful owner reclaimed them, he had to prove his purchase by producing the seller and the deed of sale or witnesses to it. Otherwise he would be adjudged a thief and die. If he proved his purchase, he had to give up the property but had his remedy against the seller or, if he had died, could reclaim five-fold from his estate. A man who bought a slave abroad, might find that he had been stolen or captured from Babylonia, and he had to restore him to his former owner without profit. If he bought property belonging to a feudal holding, or to a ward in chancery, he had to return it and forfeit what he gave for it as well. He could repudiate the purchase of a slave attacked by the bennu sickness within the month (later, a hundred days), and had a female slave three days on approval. A defect of title or undisclosed liability would invalidate the sale at any time. <^>

“Landowners frequently cultivated their land themselves but might employ a husbandman or let it. The husbandman was bound to carry out the proper cultivation, raise an average crop and leave the field in good tilth. In case the crop failed the Code fixed a statutory return. Land might be let at a fixed rent when the Code enacted that accidental loss fell on the tenant. If let on share-profit, the landlord and tenant shared the loss proportionately to their stipulated share of profit. If the tenant paid his rent and left the land in good tilth, the landlord could not interfere nor forbid subletting. Waste land was let to reclaim, the tenant being rent-free for three years and paying a stipulated rent in the fourth year. If the tenant neglected to reclaim the land the Code enacted that he must hand it over in good tilth and fixed a statutory rent. Gardens or plantations were let in the same ways and under the same conditions; but for date-groves four years' free tenure was allowed. The metayer system was in vogue, especially on temple lands. The landlord found land, labour, oxen for ploughing and working the watering-machines, carting, threshing or other implements, seed corn, rations for the workmen and fodder for the cattle. The tenant, or steward, usually had other land of his own. If he stole the seed, rations or fodder, the Code enacted that his fingers should be cut off. If he appropriated or sold the implements, impoverished or sublet the cattle, he was heavily fined and in default of payment might be condemned to be torn to pieces by the cattle on the field. Rent was as contracted. <^>

Payment and Debt in the Hammurabi Code

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“In commercial matters, payment in kind was still common, though the contracts usually stipulate for cash, naming the standard expected, that of Babylon, Larsa, Assyria, Carchemish, etc. The Code enacted, however, that a debtor must be allowed to pay in produce according to statutory scale. If a debtor had neither money nor crop, the creditor-must not refuse goods. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 <^>]

Bill of sale

“Payment through a banker or by written draft against deposit was frequent. Bonds to pay were treated as negotiable. Interest a was rarely charged on advances by the temple or wealthy land-owners for pressing needs, but this may have been part of the metayer system. The borrowers may have been tenants. Interest was charged at very high rates for overdue loans of this kind. Merchants (and even temples in some cases) made ordinary business loans, charging from 20 to 30 percent. <^>

“Debt was secured on the person of the debtor. Distraint on a debtor's corn was forbidden by the Code; not only must the creditor give it back, but his illegal action forfeited his claim altogether. An unwarranted seizure for debt was fined, as was the distraint of a working ox. The debtor being seized for debt could nominate as mancipium or hostage to work off the debt, his wife, a child, or slave. The creditor could only hold a wife or child three years as mancipium. If the mancipium died a natural death while in the creditor's possession no claim could lie against the latter; but if he was the cause of death by cruelty, he had to give son for son, or pay for a slave. He could sell a slave-hostage, unless she were a slave-girl who had borne her master children. She had to be redeemed by her owner. <^>

“The debtor could also pledge his property, and in contracts often pledged a field house or crop. The Code enacted, however, that the debtor should always take the crop himself and pay the creditor from it. If the crop failed, payment was deferred and no interest could be charged for that year. If the debtor did not cultivate the field himself he had to pay for the cultivation, but if the cultivation was already finished he must harvest it himself and pay his debt from the crop. If the cultivator did not get a crop this would not cancel his contract. Pledges were often made where the intrinsic value of the article was equivalent to the amount of the debt; but antichretic pledge was more common, where the profit of the pledge was a set-off against the interest of the debt. The whole property of the debtor might be pledged as security for the payment of the debt, without any of it coming into the enjoyment of the creditor. Personal guarantees were often given that the debtor would repay or the guarantor become liable himself." <^>

Sales and Purchases Contracts from Mesopotamia in 2000 B.C.

Contract for the Sale of Real Estate, Sumer, c. 2000 B.C." “This is a transaction from the last days of Sumerian history. It exhibits a form of transfer and title which has a flavor of modern business method about it: “Sini-Ishtar, the son of Ilu-eribu, and Apil-Ili, his brother, have bought one third Shar of land with a house constructed, next the house of Sini-Ishtar, and next the house of Minani; one third Shar of arable land next the house of Sini-Ishtar, which fronts on the street; the property of Minani, the son of Migrat-Sin, from Minani, the son of Migrat-Sin. They have paid four and a half shekels of silver, the price agreed. Never shall further claim be made, on account of the house of Minani. By their king they swore. (The names of fourteen witnesses and a scribe then follow.) Month Tebet, year of the great wall of Karra-Shamash." [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

Sales contract

Contract for the Sale of a Standing Crop, Seventh year of Cyrus, 532 B.C." This contract belongs to a class intermediate between rental and the sale of land. Instead of either, the standing crop is sold." “From a cultivated field which is situated on the alley of Li'u-Bel, Itti-Marduk-balatu, the son of Nabu-akhi-iddin, the son of Egibi, has made a purchase from Tashmitum-damqat, daughter of Shuzubu, son of Shigua, and Nadin-aplu, the son of Rimut, son of Epish-Ilu. Itti-Marduk-balatu has counted the money, the price of the crop of that field for the seventh year of Cyrus, King of Babylon, king of countries, into the hands of Tashmitum-damqat and Nadin-aplu. (The names of two witnesess and a scribe then follow) Babylon, Ululu thirteenth, the seventh year of Cyrus.

Contract for the Sale of Dates, Thirty-second year of Darius, 490 B.C." Shibtu, the place of this transaction, was a suburb of Babylon. This shows how women, especially of the lower rank, carried on business for themselves. The father of Aqubatum, as his name, Aradya [ "my slave"] shows, had been a slave. “One talent one qa of dates from the woman Nukaibu daughter of Tabnisha, and the woman Khamaza, daughter of _______, to the woman Aqubatum, daughter of Aradya. In the month Siman they will deliver one talent one qa of dates. Scribe, Shamash-zir-epish, son of Shamash-malku. Shibtu, Adar the sixth, thirty-second year of Darius, King of Babylon and countries."

Contract for the Sale of Wheat, Thirty-fifth year of Darius, 487 B.C." This tablet is a good illustration of the simple transactions in food-stuffs, of which we have many, and of which one or two additional examples are given below. The farmers usually contracted as in this document the sale of their produce far in advance of the harvest. In this instance the sale was made six months before the grain would be ripe and could be delivered. Six talents of wheat from Shamash-malku, son of Nabu-napshat-su-ziz, to Shamash-iddin, son of Rimut. In the month Siman, wheat, six talents in full, he will deliver in Shibtu, at the house of Shamash-iddin. Witnesses: Shamash-iddin, son of Nabu-usur-napishti; Abu-nu-emuq, son of Sin-akhi-iddin; Sharru-Bel, son of Sin-iddin; Aban-nimiqu-rukus, son of Malula. Scribe, Aradya, son of Epish-zir. Shibtu, eleventh of Kislimu, thirty-fifth year of Darius king of countries.

Rental Contracts from Mesopotamia in 2000 B.C.

Contract for Rent a House, One Year Term, c. 2000 B.C." This is the simplest form of rental, and comes from the early Babylonian times."Akhibte has taken the house of Mashqu from Mashqu, the owner, on a lease for one year. He will pay one shekel of silver, the rent of one year. On the fifth of Tammuz he takes possession. (Then follow the names of four witnesses.) Dated the fifth of Tammuz, the year of the wall of Kar-Shamash." [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

division of property contract

Contract for Rent & Repair of a House, One Year Term, Thirty-fifth year of Darius, 487 B.C." This contract is most interesting. Iskhuya, apparently a tenant of Shamash-iddin, undertakes to repair the house in which he is living. In addition to the rent for the year he is to receive fifteen shekels in money, in two payments, at the beginning and the completion of the work. The last payment is to be made on the day of Bel, which seems to be identical with the first of Tebet, a week later than the contract was made. In case the repairs were not then completed, Iskhuya was to forfeit four shekels. Such business methods are not, therefore, altogether modern.

“In addition to the rent of the house of Shamash-iddin, son of Rimut, for this year, fifteen shekels of money in cash (shall go) to Iskhuya, son of Shaqa-Bel, son of the priest of Agish. Because of the payment he shall repair the weakness (of the house), he shall close up the crack of the wall. He shall pay a part of the money at the beginning, a part of the money at the completion. He shall pay it on the day of Bel, the day of wailing and weeping, In case the house is unfinished by Iskhuya after the first day of Tebet, Shamash-iddin shall receive four shekels of money in cash into his possession at tne hands of Iskhuya. (The names of three witnesses and a scribe then follow.) Dated at Shibtu, the twenty-first of Kislimu, the thirty-fifth year of Darius."

Contract for Lease of Real Estate, 60 Year Term, Thirty-sixth year of Artaxerxes, 428 B.C." This complicated contract is of unusual interest, since the lease is for so long a period; the rent is paid in advance, and the lessee is in the same instrunnent guaranteed against all future contingencies. “Baga'miri, son of Mitradatu, spoke of his own free-will to Belshum-iddin, son of Murashu, saying: "I will lease my cultivated field and uncultivated land, and the cultivated field and uncultivated land of Rushundati, my father's deceased brother, which is situated on the bank of the canal of Sin, and the bank of the canal Shilikhti, and the dwelling houses in the town of Galiya, on the north, adjoining the field of Nabu-akhi-iddin, son of Ninib-iddin, and adjoining the field of Banani-erish, a citizen of Nippur; on the south, adjoining the field of Minu-Bel-dana, son of Balatu; on the east, the bank of the canal of Sin; on the west, the bank of the canal of Shilikhti, and adjoining the field of Rushundati, the overseer of Artaremu---all to use and to plant for sixty years. The rent of the cultivated field will be twenty talents of dates; and the uncultivated field (I will lease) for planting." Afterward Bel-shum-iddin, son of Murashu, accepted his offer with reference to the cultivated field and the uncultivated field, his part and the part of Rushundati, his uncle, deceased; he shall hold for sixty years the cultivated portion of it for a rental of twenty talents of dates per year, and the uncultivated portion for planting. Each year in the month Tishri, Bel-shum-iddin unto Baga'miri will give twenty talents of dates for the use of that field. The whole rent of his field for sixty years Baga'miri, son of Mitradatu, has received from the hands of Bel-shum-iddin, son of Murashu. If, in the future, before sixty years are completed, Baga'miri shall take that field from Bel-shum-iddin, Baga'miri shall pay one talent of silver to Bel-shum-iddin for the work which he shall have done on it and the orchard which he shall have planted. In case any claim should arise against that field, Baga'miri shall settle it and pay instead of Bel-shum-iddin. From the month Nisan, of the thirty-seventh year of Artaxerxes, the king, that field, for use and for planting, shall be in the possession of Bel-shum-iddin, son of Murashu, for sixty years. (The names of thirty witnesses and a scribe follow, eleven of whom left the impressions of their seals on the edges of the tablet. L. 34 states that) the print of the thumb-nail of Baga'miri was placed on the tablet instead of his seal. (L. 37 contains the information that) the tablet was written in the presence of Ekur-belit, daughter of Bel-balatu-ittannu, mother of Baga'miri. (The date is) Nippur, Tishri second, thirty-sixth year of Artaxerxes."

Co-Partnerships Contracts from Mesopotamia in 2000 B.C.

Contract for Partners to Borrow Money against Harvest, c. 2000 B.C. The two farmers who borrow the money on their crop are partners: Sin-Kalama-idi, son of Ulamasha, and Apil-ilu-shu, Son of Khayamdidu, have borrowed from Arad-Sin sixteen shekels of money for the garnering of the harvest. On the festival of Ab they will pay the wheat. (Names of three witnesses and a scribe follow, and the tablet is dated in the year of a certain flood. It is not stated in the reign of what king it was written, but it clearly is from either the dynasty of Ur III or that of Akkad." [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

proxy contract for the purchase of a slave

Contract for a Partnership, Thirty-sixth year of Nebuchadnezzar II, 568 B.C." “Nabu-akhi-iddin was an investor---a member of the great Egibi family. He contributed four manas of capital to this enterprise, while Bel-shunu, who was to carry on the business, contributed one half mana and seven shekels, whatever property he might have, and his time. His expenses in the conduct of the business up to four shekels may be paid from the common funds. Two manas of money belonging to Nabu-akhi-iddin, son of Shula, son of Egibi, and one half mana seven shekels of money belonging to Bel-shunu, son of Bel-akhi-iddin, Son of Sin-emuq, they have put into a copartnership with one another. Whatever remains to Bel-shunu in town or country over and above, becomes their common property. Whatever Bel-shunu spends for expenses in excess of four shekels of money shall be considered extravagant. (The contract is witnessed by three men and a scribe, and is dated at) Babylon, first of Ab, in the thirty-sixth year of Nebuchadnezzar."

Contract for a Partnership, Fortieth year of Nebuchadnezzar II, 564 B.C." From this document we learn that Iddin-Marduk and Nabu-ukin formed a copartnership in the month Tebet, of Nebuchadnezzar's fortieth year. A year from that date each of the partners drew out twenty shekels. In the month Ulul of the next year a number of small amounts were delivered to Iddin-Marduk for various specific purposes, and a larger amount, perhaps in payment of an obligation of the firm, was paid to two other men.

“Memorandum of the shares of Iddin-Marduk and Nabu-ukin, from the month Tebet, of the fortieth year of Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, unto the month Markheswan, of the forty-second year. One third mana of money Iddin-Marduk drew on his account in the month Tebet, of the forty-first year. One third mana of money Nabu-ukin drew on his account in the month Tebet, of the forty-first year. Fifteen shekels of Nabu-ukin's money, coined in shekel pieces, from ______ was given to Iddin-Marduk for the house of Limniya on the fifteenth of Ulul, of the forty-second year; a fourth shekel of coined money, which was for a nutu-skin, given into the same hands. One half shekel of money was given for palipi naskhapu; one third of a shekel of money was given into the same hands for beef; two giri of money was given for meat; one shekel of money was given for Lisi-nuri; two shekels of money, which was for Karia, was given into the same hands. City of _____, Markheswan ______. One mana fifty shekels are counted into the possession of Lishiru and Bunini-epish."

Laws Protecting Businesses

Morris Jastrow said: “Coming to the commercial regulations of the Code, the fundamental principle underlying them is the fixing of responsibility where it belongs, and the protecting of both parties to a transaction not only against fraud on either side, but also against unforeseen circumstances. It is somewhat significant that, although many of the laws deal with cases of wilful fraud or deceit in one party, the general assumption is that both parties are actuated by honest motives, and that difficulties often arise through no fault of either, being due to the growing complications of business activities. As a protection to buyer and seller or to any two contracting parties, it is stipulated that there must be a written contract in the presence of witnesses. No claim can be made unless a contract can be found, and the assumption is that failure to produce witnesses in case of a claim is proof of attempted fraud. An interesting case is mentioned in a series of paragraphs, of one who asserts that he has lost an article belonging to him, which he finds in the possession of another, which, however, the latter maintains that he has bought. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 <>]

“The point is to find the guilty party. The purchaser must bring into court the vendor and witnesses to the sale, and he who claims the property must bring witnesses to establish his claim. If both sets of witnesses appear and their testimony is shown to be true, the vendor of the property adjudged to be lost is revealed as the thief and is put to death, this severer punishment being inflicted because the aggravating factor of fraud is added to theft. The article is restored to the lawful owner, and the innocent purchaser is compensated out of the estate of the thief and fraudulent vendor. If the purchaser fail to produce the vendor and witnesses to the sale, and the claimant brings witnesses to prove his property, then the purchaser is put to death as the real thief, and the stolen article is restored to its lawful owner. If, on the other hand, the claimant cannot bring witnesses to prove his property, then he is considered to have made a fraudulent claim, and suffers the penalty of death. If the vendor—prove to be such—has meanwhile died, the amount is nevertheless to be restored to the purchaser out of the estate of the vendor. Finally, the law allows a term of six months within which to produce the witnesses in case they are not at once accessible. <>

“According to the ethical principles governing the Code, the directors of a bank would be responsible to the depositors for losses incurred through the business transactions of the bank. The protection of the debtor in business transactions against the tyranny of the creditor is carried almost to an extreme; it would appear that the creditor cannot attach the property of his debtor without obtaining the authority of the court; and if. e. g., he has helped himself from the granary of the debtor without the latter's permission, although he may not have taken more than the amount of the debt, he must return what he has taken, and by his wilful act forfeits his original claim. The courts regulated the hire of cattle for ploughing or other purposes, the wages of mechanics and labourers, the hire of ships for freight, the amount of the return for the farming of fields, and even the fee of surgeons for operations—all with a view to affording protection against both extortion and underpayment.

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 100-112: Merchants and Tavern and Inn-Keepers

The Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.) is credited with producing the Code of Hammurabi, the oldest surviving set of laws. Recognized for putting eye for an eye justice into writing and remarkable for its depth and judiciousness, it consists of 282 case laws with legal procedures and penalties. Many of the laws had been around before the code was etched in the eight-foot-highin black diorite stone that bears them. Hammurabi codified them into a fixed and standardized set of laws. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

100. . . . interest for the money, as much as he has received, he shall give a note therefor, and on the day, when they settle, pay to the merchant.

101. If there are no mercantile arrangements in the place whither he went, he shall leave the entire amount of money which he received with the broker to give to the merchant.

102. If a merchant entrust money to an agent (broker) for some investment, and the broker suffer a loss in the place to which he goes, he shall make good the capital to the merchant.

103. If, while on the journey, an enemy take away from him anything that he had, the broker shall swear by God and be free of obligation.

104. If a merchant give an agent corn, wool, oil, or any other goods to transport, the agent shall give a receipt for the amount, and compensate the merchant therefor. Then he shall obtain a receipt form the merchant for the money that he gives the merchant.

105. If the agent is careless, and does not take a receipt for the money which he gave the merchant, he can not consider the unreceipted money as his own.

106. If the agent accept money from the merchant, but have a quarrel with the merchant (denying the receipt), then shall the merchant swear before God and witnesses that he has given this money to the agent, and the agent shall pay him three times the sum.

107. If the merchant cheat the agent, in that as the latter has returned to him all that had been given him, but the merchant denies the receipt of what had been returned to him, then shall this agent convict the merchant before God and the judges, and if he still deny receiving what the agent had given him shall pay six times the sum to the agent.

108. If a tavern-keeper (feminine) does not accept corn according to gross weight in payment of drink, but takes money, and the price of the drink is less than that of the corn, she shall be convicted and thrown into the water.

109. If conspirators meet in the house of a tavern-keeper, and these conspirators are not captured and delivered to the court, the tavern-keeper shall be put to death.

110. If a "sister of a god" open a tavern, or enter a tavern to drink, then shall this woman be burned to death.

111. If an inn-keeper furnish sixty ka of usakani-drink to . . . she shall receive fifty ka of corn at the harvest.

112. If any one be on a journey and entrust silver, gold, precious stones, or any movable property to another, and wish to recover it from him; if the latter do not bring all of the property to the appointed place, but appropriate it to his own use, then shall this man, who did not bring the property to hand it over, be convicted, and he shall pay fivefold for all that had been entrusted to him.

Balance sheet from Sumer

Hammurabi's Code of Laws: 113-126: Claims and Debts

113. If any one have consignment of corn or money, and he take from the granary or box without the knowledge of the owner, then shall he who took corn without the knowledge of the owner out of the granary or money out of the box be legally convicted, and repay the corn he has taken. And he shall lose whatever commission was paid to him, or due him. [Source: Translated by L. W. King]

114. If a man have no claim on another for corn and money, and try to demand it by force, he shall pay one-third of a mina of silver in every case.

115. If any one have a claim for corn or money upon another and imprison him; if the prisoner die in prison a natural death, the case shall go no further.

116. If the prisoner die in prison from blows or maltreatment, the master of the prisoner shall convict the merchant before the judge. If he was a free-born man, the son of the merchant shall be put to death; if it was a slave, he shall pay one-third of a mina of gold, and all that the master of the prisoner gave he shall forfeit.

117. If any one fail to meet a claim for debt, and sell himself, his wife, his son, and daughter for money or give them away to forced labor: they shall work for three years in the house of the man who bought them, or the proprietor, and in the fourth year they shall be set free.

118. If he give a male or female slave away for forced labor, and the merchant sublease them, or sell them for money, no objection can be raised.

119. If any one fail to meet a claim for debt, and he sell the maid servant who has borne him children, for money, the money which the merchant has paid shall be repaid to him by the owner of the slave and she shall be freed.

120. If any one store corn for safe keeping in another person's house, and any harm happen to the corn in storage, or if the owner of the house open the granary and take some of the corn, or if especially he deny that the corn was stored in his house: then the owner of the corn shall claim his corn before God (on oath), and the owner of the house shall pay its owner for all of the corn that he took.

121. If any one store corn in another man's house he shall pay him storage at the rate of one gur for every five ka of corn per year.

122. If any one give another silver, gold, or anything else to keep, he shall show everything to some witness, draw up a contract, and then hand it over for safe keeping.

123. If he turn it over for safe keeping without witness or contract, and if he to whom it was given deny it, then he has no legitimate claim.

124. If any one deliver silver, gold, or anything else to another for safe keeping, before a witness, but he deny it, he shall be brought before a judge, and all that he has denied he shall pay in full.

125. If any one place his property with another for safe keeping, and there, either through thieves or robbers, his property and the property of the other man be lost, the owner of the house, through whose neglect the loss took place, shall compensate the owner for all that was given to him in charge. But the owner of the house shall try to follow up and recover his property, and take it away from the thief.

126. If any one who has not lost his goods state that they have been lost, and make false claims: if he claim his goods and amount of injury before God, even though he has not lost them, he shall be fully compensated for all his loss claimed. (I.e., the oath is all that is needed.)

Loans and Mortgages Contracts from Mesopotamia in 611 B.C.

tablet with accounts from Ur around 2000 BC

Contract for Loan of Money, Fourteenth year of Nabopolassar, 611 B.C. This is a mortgage on real estate in security for a loan. The interest was at the rate of eleven and one-third per cent: “One mana of money, a sum belonging to Iqisha-Marduk, son of Kalab-Sin, (is loaned) unto Nabu-etir, son of _____, son of _____. Yearly the amount of the mana shall increase its sum by seven shekels of money. His field near the gate of Bel is Iqisha-Marduk's pledge. (This document bears the name of four witnesses, and is dated) at Babylon, Tammuz twenty-seventh, in the fourteenth year of Nabopolassar, (the father of Nebuchadnezzar)." [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

Contract for Loan of Money, Sixth year of Nebuchadnezzar II, 598 B.C." The rate of interest in this case was thirteen and one-third per cent. “One mana of money, a sum belonging to Dan-Marduk, son of Apla, son of the Dagger-wearer, (is loaned) unto Kudurru, son of Iqisha-apla, son of Egibi. Yearly the amount of the mana shall increase its sum by eight shekels of money. Whatever he has in city or country, as much as it may be, is pledged to Dan-Marduk. (The date is) Babylon, Adar fourth, in Nebuchadnezzar's sixth year."

Contract for Loan of Money, Fifth year of Nabonidus, 550 B.C. This loan was made Aru third, in the fifth year of Nabonidus. No security was given the creditor, but he received an interest of twenty per cent: “One and a half manas of money belonging to Iddin-Marduk, son of Iqisha-apla, son of Nur-Sin, (is loaned) unto Ben-Hadad-natan, son of Addiya and Bunanit, his wife. Monthly the amount of a mana shall increase its sum by a shekel of money. From the first of the month Siman, of the fifth year of Nabonidus, King of Babylon, they shall pay the sum on the money. The call shall be made for the interest money at the house which belongs to Iba. Monthly shall the sum be paid."

Bankruptcy Contracts from Mesopotamia in 560 B.C.

Contract for Purchase of Mortgage, Second year of Evil-Merodach, 560 B.C. It exhibits how in a case of bankruptcy the interests of the creditor were conserved in the sale of the mortgaged property. It also proves that in Babylonian law the value of the estate was not in such cases sacrificed to the creditor, but that the debtor could obtain the equity in his property which actually belonged to him. [Source: George Aaron Barton, "Contracts," in Assyrian and Babylonian Literature: Selected Transactions, With a Critical Introduction by Robert Francis Harper (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1904), pp. 256-276, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]