市場の失敗(Wikipedia、八田達夫、ゲーリー・ベッカー)

ナイト他

産業組織論

(1968). The Organization of Industry. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin

邦訳1975年

目次

序言

日本語版への序

第1章

産業組織論とは何か

第1部 競争とは何か,独占とは何か

第2章競争

第3章 価格競争と非価格競争

第4章集中度の測定

第5章寡占の理論

第Ⅱ部 集中度の決定要因

第6章参入障壁および規模の経済と企業規模

第7章規模の経済

第8章合併による独占および寡占

第9章優位企業の仮説と温床の仮説…

第10章資本市場の不完全性

第11章特許権に関する覚え書

第Ⅲ部 市場行動の諸問題

第12章 分業は市場の広さによって制約される

第13章収益性,競争および集中に関する覚え書

第14章受渡し価格の理論

第15章抱合せ契約に関する覚え書

第16章情報の経済学

第17章労働市場における情報

第18章屈折需要曲線の理論と価格の硬直性

第19章管理価格と寡占インフレーション

第Ⅳ部 独占禁止政策

第20章不成文法に基づく取引の制限

第21章 独占禁止法の経済的効果

第22章 合併と予防的独占禁止政策

付録 独占的競争理論の回顧

訳者あとがき

索引

スウィージー(Sweezy)のモデル:

[アメリカの経済学者スウィージー(1910-2004)は論文「需要と寡占の状態」(1939年)において、たとえカルテルによる価格協定が存在しなくとも価格が硬直的になりうることを説明した。スウィージーもチェンバリン同様に2組の需要曲線を用いた。しかし、別々の2本の曲線としてではなく、途中で折れ曲がる1本の需要曲線にまとめ上げた。この曲線はその形状から「屈折需要曲線」と名づけられた。

Paul M. Sweezy, “Demand Under Conditions of Oligopoly,” Journal of Political Economy (1939)

R. L.ホール(R. L.Hall)とC. J. ヒッチ(C. J. Hitch)のモデル:

[ホールとヒッチは、企業は需要曲線を認識できないためにフル・コスト原則をとらざるをえないと考えた。 ]

___

ジョージ・J.スティグラー 著, 余語将尊, 宇佐美泰生 訳

東洋経済新報社, 1981.9

冊子体 ; 333, 3p ; 20cm

タイトル 小さな政府の経済学 : 規制と競争

著者 ジョージ・J.スティグラー 著

余語将尊, 宇佐美泰生 訳

出版事項 東京 : 東洋経済新報社

出版年月日等 1981.9

大きさ、容量等 333, 3p ; 20cm

別タイトル The citizen and the state:essays on regulation

注記 原タイトル: The citizen and the state:essays on regulation

価格 2800円 (税込)

著者標目 Stigler, George Joseph, 1911-1991

目次

日本語版序文

序言

第1部 自由に関する論争

第一章 噛みあわない論争

第二章自由に関する所見

第2部 伝統的規制ーー証拠不十分

第三章 経済改革の戦略

第四章 経済学者と国家

第3部 伝統的規制ーーいくつかの証拠

第五章 規制当局者は何を規制できるかーー電力の場合

第六章 証券市場の公的規制

第4部 規制の新旧経済理論

第七章 国家の経済的機能に対する経済学者の伝統的理論

第八章 経済規制の理論

第5部 拡張と応用

第九章 経済規制の過程

第一〇章 規制ーー手段と目的の混同

第一一章 規制当局は消費者を規制できるか

第一二章 教育における真実の歴史的点描

付録 説教師としての経済学者

訳者後記

索引(巻末)

The Theory of Economic Regulation Author(s): George J. Stigler Reviewed work(s): Source: The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 1971), pp. 3-21

1971 (邦訳「経済規制の理論」『小さな政府の経済学』#8)

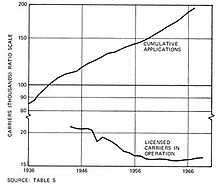

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) as Barrier-to-Competition: Applications-to-Operate vs In-Operation

The interstate motor carrier history is in some respects even more striking, because no even ostensibly respectable case for restriction on entry can be developed on grounds of scale economies (which are in turn adduced to limit entry for safety or economy of operation). The number of federally licensed common carriers is shown in Figure 1: the immense growth of the freight hauled by trucking common carriers has been associated with a steady secular decline of numbers of such carriers. The number of applications for new certificates has been in excess of 5000 annually in recent years: a rigorous proof that hope springs eternal in an aspiring trucker's breast. We propose the general hypothesis: every industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to con- trol entry. In addition, the regulatory policy will often be so fashioned as to retard the rate of growth of new firms. For example, no new savings and loan company may pay a dividend rate higher than that prevailing in the community in its endeavors to attract deposits.

Figure1:CERTIFICATES FOR INTERSTATE MOTOR CARRIERS

縦軸

運送会社(千単位)比指数

累積申請件数

就業中の認可業者数

…州際自動車運輸の認可の歴史は、ある点でもっと目を見張るものがある。というのも、これは、どのようにうわべを取り繕った議論も、規模の経済性を理由にして参入制限を擁護することはできないからである(規模の経済性は、操業の安全性や経済性とならんで、参入を制限する根拠として指摘される)。連邦の認可を受けた運輸会社の数が、図8-1に示されている。トラック運輸会社の運行便数の急激な増加と、そのような運輸会社の数の持続的な減少とが並行している。新しい認可証の申請件数は、近年、年五000件を超えている。認可を待ち望むトラック運送業者が、決して望みを失わないことを、はっきりと示すものであろう。

一般的仮説を提起しよう。国家を利用するだけの政治力をもつあらゆる産業、あるいはあらゆる職

業は、参入規制を求めるとしよう。また、規制政策は、往々、新規企業の成長率を引き下げるような

かたちをとるとしよう。たとえば、新規の貯蓄貸付会社は、預金獲得のために、その地域で支配的な

配当率以上のものを支払うことは許されないかもしれない。オープン·エンド型投資会社の販売費用

を規制する権限が、間もなく証券取引委員会に与えられ、中小のオープン·エンド型投資会社の成長

を制約し,結果として大きなオープン·エンド型投資会社の販売費用を引き下げる働きをするであろう。

邦訳小さな政府184~5頁

1971

...原則として、規制は業界によって獲得され、主にその利益のために設計され運営されています...私たちは一般的な仮説を提案します。 加えて、規制方針はしばしば新会社の成長率を遅らせるように作られています。

- 経済規制論、ジョージ・スティグラー、1971年[3]google翻訳

193:

消費投票説もスティグラー:

たとえば、消費者が鉄道と空の旅のどちらかを選択する場合には、財布と相談して投票しているのである。つまり、旅行当日には、彼の好む輸送手段を支援していることになる。どこで働いたらよいか、資本を何に投資したらよいか、という決定の際にも、同じようなかたちの経済的投票が行なわれている。市場は、このような経済的投票を累積し、その将来の投票動向を予測し、それにもとづいて投資する。

_______

スティグラー

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2019/02/httpsja.html@

業績

- スティグラーは産業組織論や経済学史を主領域として研究を行っていた。スティグラーは産業組織論において、20世紀前半の主流派であったハーバード学派に対抗して、市場構造の集中度の高さが必ずしも市場の非効率性につながらないことなどを示した。また従来は価格と経済という現象にのみ適用されていた新古典派経済学をゲーリー・ベッカーとともに拡張し、あらゆる行動は合理的に選択されているという点を示したことでも有名である。

- また本来は消費者保護のためであったはずの規制が、いつの間にか生産者保護のための規制に転換してしまうという現象(規制の虜)のメカニズムを明らかにした。スティグラーはこの見地から、規制よりも市場構造に重点を置いた政策を支持する主張を行った。

日本語訳著書編集

- 『価格の理論(上・下)』(有斐閣, 1963年)

- 『生産と分配の理論――限界生産力理論の形成期』(東洋経済新報社, 1967年)

- 『産業組織論』(東洋経済新報社, 1975年)

- 『効用理論の発展』(日本経済新聞社, 1979年)

- 『小さな政府の経済学――規制と競争』(東洋経済新報社, 1981年)

- 『現代経済学の回想――アメリカ・アカデミズムの盛衰』(日本経済新聞社, 1990年)

外部リンク編集

ーーー

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Stigler

- ([1941] 1994). Production and Distribution Theories: The Formative Period. New York: Macmillan. Preview.

- (1961). "The Economics of Information," Journal of Political Economy, 69(3), pp. 213–25

- (1962a). "Information in the Labor Market." Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), Part 2, pp. 94–105

- (1962b). The Intellectual and the Marketplace. Selected Papers, no. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. Reprinted in Sigler (1986), pp. 79–88

- (1963). (With Paul Samuelson) "A Dialogue on the Proper Economic Role of the State." Selected Papers, no. 7. pp. 3–20. Chicago: University of Chicago Graduate School of Business

- (1963). Capital and Rates of Return in Manufacturing Industries. National Bureau of Economic Research, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press

- (1965). Essays in the History of Economics. University of Chicago Press. 1965.

- (1968). The Organization of Industry. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin

- (1970). (With J.K. Kindahl) The Behavior of Industrial Prices. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York: Columbia University Press

- (1971). "The Theory of Economic Regulation." Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, no. 3, pp. 3–18

- (1975). Citizen and the State: Essays on Regulation

- (1982). "The Process and Progress of Economics," Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December (with bibliography)

- (1982). The Economist as Preacher, and Other Essays. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- (1983). The Organization of Industry

- (1985). Memoirs of an Unregulated Economist. University of Chicago Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-226-77440-4. autobiography

- (1986). The Essence of Stigler, K.R. Leube and T.G. Moore, ed. Scroll or page-arrow to respective essays. ISBN 0-8179-8462-3

- (1987). The Theory of Price, Fourth Edition. New York: Macmillan

- (1988). ed. Chicago Studies in Political Economy

《…規制する側が規制される側に取り込まれて、規制が規制される側に都合よく歪曲されるメカニズムを「規制の虜」という。ノーベル賞経済学者ジョージ・スティグラーが唱えた理論だ。もっとも日本では「官民の癒着」というのはよく見られる構図だ。規制者側に専門知識がないと、簡単に取り込まれる。ちなみに霞が関では、役人が電力会社から接待を受けてヘナヘナになることを「感電」すると言っていた。相手がガス会社の場合は「ガス中毒」だ。「規制の虜」のキモである「天下り」という言葉は、野村修也委員(弁護士)のメッセージに見られるだけだが、脱官僚で政権交代したはずの民主党が政権を担っても、形を変えて「天下り」は継続された。天下りによる「規制の皮はどの官庁でも見られることであり、事の軽重は異なるが, どの役所にも「東電問題」はあると思うべきだ。》

著者: 高橋洋一、 ザイ編集部

めちゃくちゃうれてるマネー誌ZAiが作った世界で一番わかりやすいニッポンの論点10 2013

___

規制の虜(きせいのとりこ、英:Regulatory Captureとは、規制機関が被規制側の勢力に実質的に支配されてしまうような状況であり、この状況下では、被規制産業が規制当局をコントロールできてしまう余地がありうる。政府の失敗の1つである。その場合には、負の外部性が発生しており、そのような規制当局は、「虜にされた規制当局(captured agencies)」と呼ばれる。

- Stigler, George (1915). "The Theory of Economic Regulation" (PDF). Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, (Spring, 1971). pp. 3–21.

Regulatory capture is a form of government failure which occurs when a regulatory agency, created to act in the public interest, instead advances the commercial or political concerns of special interest groups that dominate the industry or sector it is charged with regulating.[1] When regulatory capture occurs, the interests of firms or political groups are prioritized over the interests of the public, leading to a net loss for society. Government agencies suffering regulatory capture are called "captured agencies".

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) as Barrier-to-Competition: Applications-to-Operate vs In-Operation

For public choice theorists, regulatory capture occurs because groups or individuals with a high-stakes interest in the outcome of policy or regulatory decisions can be expected to focus their resources and energies in attempting to gain the policy outcomes they prefer, while members of the public, each with only a tiny individual stake in the outcome, will ignore it altogether.[2] Regulatory capture refers to the actions by interest groups when this imbalance of focused resources devoted to a particular policy outcome is successful at "capturing" influence with the staff or commission members of the regulatory agency, so that the preferred policy outcomes of the special interest groups are implemented.

... as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit... We propose the general hypothesis: every industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to control entry. In addition, the regulatory policy will often be so fashioned as to retard the rate of growth of new firms.

-- The Theory of Economic Regulation, George Stigler, 1971[3]

Regulatory capture theory is a core focus of the branch of public choice referred to as the economics of regulation; economists in this specialty are critical of conceptualizations of governmental regulatory intervention as being motivated to protect public good. Often cited articles include Bernstein (1955), Huntington (1952), Laffont & Tirole (1991), and Levine & Forrence (1990). The theory of regulatory capture is associated with Nobel laureate economist George Stigler,[4] one of its main developers.[5]

Likelihood of regulatory capture is a risk to which an agency is exposed by its very nature.[6] This suggests that a regulatory agency should be protected from outside influence as much as possible. Alternatively, it may be better to not create a given agency at all lest the agency become victim, in which case it may serve its regulated subjects rather than those whom the agency was designed to protect. A captured regulatory agency is often worse than no regulation, because it wields the authority of government. However, increased transparency of the agency may mitigate the effects of capture. Recent evidence suggests that, even in mature democracies with high levels of transparency and media freedom, more extensive and complex regulatory environments are associated with higher levels of corruption (including regulatory capture).[7]

Relationship with federalismEdit

There is substantial academic literature suggesting that smaller government units are easier for small, concentrated industries to capture than large ones. For example, a group of states or provinces with a large timber industry might have their legislature and/or their delegation to the national legislature captured by lumber companies. These states or provinces then becomes the voice of the industry, even to the point of blocking national policies that would be preferred by the majority across the whole federation. Moore and Giovinazzo (2012) call this "distortion gap".[8]

The opposite scenario is possible with very large industries, however. Very large and powerful industries (e.g. energy, banking, weapon system construction) can capture national governments, and then use that power to block policies at the federal, state or provincial level that the voters may want,[9] although even local interests can thwart national priorities.[10]

Economic rationaleEdit

The idea of regulatory capture has an obvious economic basis, in that vested interests in an industry have the greatest financial stake in regulatory activity and are more likely to be motivated to influence the regulatory body than dispersed individual consumers,[2] each of whom has little particular incentive to try to influence regulators. When regulators form expert bodies to examine policy, this invariably features current or former industry members, or at the very least, individuals with contacts in the industry. Capture is also facilitated in situations where consumers or taxpayers have a poor understanding of underlying issues and businesses enjoy a knowledge advantage.[11]

Some economists, such as Jon Hanson and his co-authors, argue that the phenomenon extends beyond just political agencies and organizations. Businesses have an incentive to control anything that has power over them, including institutions from the media, academia and popular culture, thus they will try to capture them as well. This phenomenon is called "deep capture".[12]

Regulatory public interest is based on market failure and welfare economics. It holds that regulation is the response of the government to public needs. Its purpose is to make up for market failures, improve the efficiency of resource allocation, and maximize social welfare. Posner pointed out that the public interest theory contains the assumption that the market is fragile, and that if left unchecked, it will tend to be unfair and inefficient, and government regulation is a costless and effective way to meet the needs of social justice and efficiency. Mimik believes that government regulation is a public administration policy that focuses on private behavior. It is a rule drawn from the public interest. Irving and Brouhingan saw regulation as a way of obeying public needs and weakening the risk of market operations. It also expressed the view that regulation reflects the public interest.

DevelopmentEdit

The review of the United States' history of regulation at the end of the 19th century,[clarification needed]especially the regulation of railway tariffs by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887, revealed that regulations and market failures are not co-relevant. At least until the 1960s, in terms of regulatory experience, regulation was developed in the direction of favoring producers, and regulation increased the profits of manufacturers within the industry. In potentially competitive industries such as the trucking industry and the taxi industry, regulations allow pricing to be higher than cost and prevent entrants. In the natural monopoly industries such as the electric power industry, there are facts that regulation has little effect on prices, so the industry can earn profits above normal profits. Empirical evidence proves that regulation is beneficial to producers.[citation needed]

These empirical observations have led to the emergence and development of regulatory capture theory. Contrary to regulatory public interest theory, regulation capture theory holds that the provision of regulation is adapting to the industry's need for regulation, that is, the legislator is controlled and captured by the industry in regulation, and the regulation institution is gradually controlled by the industry. That is, the regulator is captured by the industry. The basic view of the regulatory capture theory is that no matter how the regulatory scheme is designed, the regulation of an industry by a regulatory agency is actually "captured" by the industry. The implication is that regulation increases the profits of the industry rather than social welfare.[citation needed]

The above-mentioned regulatory capture theory is essentially a purely capture theory in the early days, that is, the regulators and legislators were captured and controlled by the industry. The later regulatory models such as Stiegler (Stigler Model)-Pelzmann (Pelzmann Model)-Becker (Becker Model) belong to the regulatory capture theory in the eyes of Posner (1974) and others. Because these models all reflect that regulators and legislators are not pursuing the maximization of public interests, but the maximization of private interests, that is, using "private interest" theory to explain the origin and purpose of regulation. Aton (1986) argues that Stigler's theoretical logic is clear and more central than the previous "capture theory" hypothesis, but it is difficult to distinguish between the two.[citation needed]

Regulatory capture theory has a specific meaning, that is, an experience statement that regulations are beneficial for producers in real life. In fact, it is essentially not a true regulatory theory. Although the analysis results are similar to the Stigler model provide interpretation and support for the regulatory capture theory is beneficial for producers, however the analysis methods of the latter are completely different. Stigler used standard economic analysis methods to analyze the regulation behavior, then created a new regulatory theory - regulatory economic theory. Of course, different divisions depend on the criteria for division, and they essentially depend on the researchers' different understanding of specific concepts.[citation needed]

There are two basic types of regulatory capture:[13][14]

- Materialist capture, also called financial capture, in which the captured regulator's motive is based on its material self-interest. This can result from bribery, revolving doors, political donations, or the regulator's desire to maintain its government funding. These forms of capture often amount to political corruption.

- Non-materialist capture, also called cognitive capture or cultural capture, in which the regulator begins to think like the regulated industry. This can result from interest-group lobbying by the industry.

Another distinction can be made between capture retained by big firms and by small firms.[15] While Stigler mainly referred, in his work,[16] to large firms capturing regulators by bartering their vast resources (materialist capture) – small firms are more prone to retain non-materialist capture via a special underdog rhetoric.[15]

United States examplesEdit

Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and EnforcementEdit

In the aftermath of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the Minerals Management Service (MMS), which had regulatory responsibility for offshore oil drilling, was widely cited as an example of regulatory capture.[17][18] The MMS then became the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEMRE) and on October 1, 2010, the collection of mineral leases was split off from the agency and placed under the Department of the Interior as the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR). On October 1, 2011, BOEMRE was then split into two bureaus, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).[19]

The three-stage reorganization, including the name change to BOEMRE, was part of a re-organization by Ken Salazar,[19] who was sworn into office as the new Secretary of the Interior on the same day the name change was announced.[20] Salazar's appointment was controversial because of his ties to the energy industry.[21] As a senator, Salazar voted against an amendment to repeal tax breaks for ExxonMobil and other major petroleum companies[22] and in 2006, he voted to end protections that limit offshore oil drillingin Florida's Gulf Coast.[23] One of Salazar's immediate tasks was to "[end] the department's coziness with the industries it regulates"[21] but Daniel R. Patterson, a member of the Arizona House of Representatives, said "Salazar has a disturbingly weak conservation record, particularly on energy development, global warming, endangered wildlife and protecting scientific integrity. It's no surprise oil and gas, mining, agribusiness and other polluting industries that have dominated Interior are supporting rancher Salazar – he's their friend."[21] Indeed, a spokesman for the National Mining Association, which lobbies for the mining industry, praised Salazar, saying that he was not doctrinaire about the use of public lands.[21]

MMS had allowed BP and dozens of other companies to drill in the Gulf of Mexico without first attaining permits to assess threats to endangered species, as required by law.[24] BP and other companies were also given a blanket exemption (categorical exclusion)[25] from having to provide environmental impact statements.[24] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued strong warnings about the risks posed by such drilling and in a 2009 letter, accused MMS of understating the likelihood and potential consequences of a major spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[24] The letter further accused MMS of highlighting the safety of offshore drilling while understating the risks and impact of spills and playing down the fact that spills had been increasing.[24] Both current and former MMS staff scientists said their reports were overruled and altered if they found high risk of accident or environmental impact.[24] Kieran Suckling, director of the Center for Biological Diversity, said, "MMS has given up any pretense of regulating the offshore oil industry. The agency seems to think its mission is to help the oil industry evade environmental laws."[24]

After the Deepwater accident occurred, Salazar said he would delay granting any further drilling permits. Three weeks later, at least five more permits had been issued by the minerals agency.[24] In March 2011, BOEMRE began issuing more offshore drilling permits in the Gulf of Mexico.[26] Michael Bromwich, head of BOEMRE, said he was disturbed by the speed at which some oil and gas companies were shrugging off Deepwater Horizon as "a complete aberration, a perfect storm, one in a million," but would nonetheless soon be granting more permits to drill for oil and gas in the gulf.[26]

Commodity Futures Trading CommissionEdit

In October 2010, George H. Painter, one of the two Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) administrative law judges, retired, and in the process requested that his cases not be assigned to the other judge, Bruce C. Levine.[27] Painter wrote, "On Judge Levine's first week on the job, nearly twenty years ago, he came into my office and stated that he had promised Wendy Gramm, then Chairwoman of the Commission, that we would never rule in a complainant's favor," Painter wrote.[27] "A review of his rulings will confirm that he fulfilled his vow." In further explaining his request, he wrote, "Judge Levine, in the cynical guise of enforcing the rules, forces pro se complainants to run a hostile procedural gauntlet until they lose hope, and either withdraw their complaint or settle for a pittance, regardless of the merits of the case."[27] Gramm, wife of former Senator Phil Gramm, was accused of helping Goldman Sachs, Enron and other large firms gain influence over the commodity markets. After leaving the CFTC, Wendy Gramm joined the board of Enron.[27]

Environmental Protection AgencyEdit

Natural gas drilling increased in the United States after the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said in 2004 that hydraulic fracturing "posed little or no threat" to drinking water.[28] Also known as "fracking", the process was invented by Halliburton in the 1940s.[29] Whistleblower Weston Wilson says that the EPA's conclusions were "unsupportable" and that five of the seven-member review panel that made the decision had conflicts of interest.[28] A New York Times editorial said the 2004 study "whitewashed the industry and was dismissed by experts as superficial and politically motivated."[29] The EPA is currently prohibited by law from regulating fracking, the result of the "Halliburton Loophole," a clause added to the 2005 energy bill at the request of then-vice president Dick Cheney, who was CEO of Halliburton before becoming vice president.[28][29] Legislation to close the loophole and restore the EPA's authority to regulate hydraulic fracturing has been referred to committee in both the House and the Senate.[30][31]

Federal Aviation AdministrationEdit

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has a dual-mandate both to promote aviation and to regulate its safety. A report by the Department of Transportation that found FAA managers had allowed Southwest Airlines to fly 46 airplanes in 2006 and 2007 that were overdue for safety inspections, ignoring concerns raised by inspectors. Audits of other airlines resulted in two airlines grounding hundreds of planes, causing thousands of flight cancellations.[32] The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee investigated the matter after two FAA whistleblowers, inspectors Charalambe "Bobby" Boutris and Douglas E. Peters, contacted them. Boutris said he attempted to ground Southwest after finding cracks in the fuselage, but was prevented by supervisors he said were friendly with the airline.[33] The committee subsequently held hearings in April 2008. James Oberstar, former chairman of the committee said its investigation uncovered a pattern of regulatory abuse and widespread regulatory lapses, allowing 117 aircraft to be operated commercially although not in compliance with FAA safety rules.[33] Oberstar said there was a "culture of coziness" between senior FAA officials and the airlines and "a systematic breakdown" in the FAA's culture that resulted in "malfeasance, bordering on corruption."[33]

On July 22, 2008, a bill was unanimously approved in the House to tighten regulations concerning airplane maintenance procedures, including the establishment of a whistleblower office and a two-year "cooling off" period that FAA inspectors or supervisors of inspectors must wait before they can work for those they regulated.[32][34] The bill also required rotation of principal maintenance inspectors and stipulated that the word "customer" properly applies to the flying public, not those entities regulated by the FAA.[32] The bill died in a Senate committee that year.[35] In 2008 the FAA proposed to fine Southwest $10.2 million for failing to inspect older planes for cracks,[36] and in 2009 Southwest and the FAA agreed that Southwest would pay a $7.5 million penalty and would adapt new safety procedures, with the fine doubling if Southwest failed to follow through.[37] In September 2009, the FAA administrator issued a directive mandating that the agency use the term "customers" only to refer to the flying public.[38]

In a June 2010 article on regulatory capture, the FAA was cited as an example of "old-style" regulatory capture, "in which the airline industry openly dictates to its regulators its governing rules, arranging for not only beneficial regulation but placing key people to head these regulators."[41]

Federal Communications CommissionEdit

Legal scholars have pointed to the possibility that federal agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had been captured by media conglomerates. Peter Schuck of Yale Law School has argued that the FCC is subject to capture by the media industries' leaders and therefore reinforce the operation of corporate cartels in a form of "corporate socialism" that serves to "regressively tax consumers, impoverish small firms, inhibit new entry, stifle innovation, and diminish consumer choice".[42] The FCC selectively granted communications licenses to some radio and television stations in a process that excludes other citizens and little stations from having access to the public.[43]

Meredith Attwell Baker was one of the FCC commissioners who approved a controversial merger between NBC Universal and Comcast. Four months later, she announced her resignation from the FCC to join Comcast's Washington, D.C. lobbying office.[45] Legally, she is prevented from lobbying anyone at the FCC for two years and an agreement made by Comcast with the FCC as a condition of approving the merger will ban her from lobbying any executive branch agency for life.[45] Nonetheless, Craig Aaron, of Free Press, who opposed the merger, complained that "the complete capture of government by industry barely raises any eyebrows" and said public policy would continue to suffer from the "continuously revolving door at the FCC".[45]

Federal Reserve Bank of New YorkEdit

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (New York Fed) is the most influential of the Federal Reserve Banking System. Part of the New York Fed's responsibilities is the regulation of Wall Street, but its president is selected by and reports to a board dominated by the chief executives of some of the banks it oversees.[47] While the New York Fed has always had a closer relationship with Wall Street, during the years that Timothy Geithner was president, he became unusually close with the scions of Wall Street banks,[47] a time when banks and hedge funds were pursuing investment strategies that caused the 2008 financial crisis, which the Fed failed to stop.

During the financial crisis, several major banks that were on the verge of collapse were rescued with government emergency funding.[47] Geithner engineered the New York Fed's purchase of $30 billion of credit default swaps from American International Group (AIG), which it had sold to Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, Deutsche Bank and Société Générale. By purchasing these contracts, the banks received a "back-door bailout" of 100 cents on the dollar for the contracts.[48] Had the New York Fed allowed AIG to fail, the contracts would have been worth much less, resulting in much lower costs for any taxpayer-funded bailout.[48] Geithner defended his use[48] of unprecedented amounts of taxpayer funds to save the banks from their own mistakes,[47] saying the financial system would have been threatened. At the January 2010 congressional hearing into the AIG bailout, the New York Fed initially refused to identify the counterpartiesthat benefited from AIG's bailout, claiming the information would harm AIG.[48] When it became apparent this information would become public, a legal staffer at the New York Fed e-mailed colleagues to warn them, lamenting the difficulty of continuing to keep Congress in the dark.[48] Jim Rickards calls the bailout a crime and says "the regulatory system has become captive to the banks and the non-banks".[49]

Interstate Commerce CommissionEdit

Historians, political scientists, and economists have often used the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), a now-defunct federal regulatory body in the United States, as a classic example of regulatory capture. The creation of the ICC was the result of widespread and longstanding anti-railroad agitation. Richard Olneyjoined the Grover Cleveland administration as attorney general not long after the ICC was established. Olney, formerly a prominent railroad lawyer, was asked if he could do something to get rid of the ICC.[17] He replied,

The Commission… is, or can be made, of great use to the railroads. It satisfies the popular clamor for a government supervision of the railroads, at the same time that supervision is almost entirely nominal. Further, the older such a commission gets to be, the more inclined it will be found to take the business and railroad view of things.… The part of wisdom is not to destroy the Commission, but to utilize it.[17]

Nuclear Regulatory CommissionEdit

Nuclear power is a textbook example of the problem of "regulatory capture"—in which an industry gains control of an agency meant to regulate it. Regulatory capture can be countered only by vigorous public scrutiny and Congressional oversight, but in the 32 years since Three Mile Island, interest in nuclear regulation has declined precipitously.[52]

Then-candidate Barack Obama said in 2007 that the five-member NRC had become "captive of the industries that it regulates" and Joe Biden indicated he had absolutely no confidence in the agency.[53]

The NRC has given a license to "every single reactor requesting one", according to Greenpeace USAnuclear policy analyst Jim Riccio to refer to the agency approval process as a "rubber stamp".[54] In Vermont, ten days after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that damaged Japan's Daiichi plant in Fukushima, the NRC approved a 20-year extension for the license of Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant, although the Vermont state legislature had voted overwhelmingly to deny such an extension.[54][55] The Vermont plant uses the same GE Mark 1 reactor design as the Fukushima Daiichi plant.[54] The plant had been found to be leaking radioactive materials through a network of underground pipes, which Entergy, the company running the plant, had denied under oath even existed. Representative Tony Klein, who chaired the Vermont House Natural Resources and Energy Committee, said that when he asked the NRC about the pipes at a hearing in 2009, the NRC didn't know about their existence, much less that they were leaking.[54]On March 17, 2011, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) released a study critical of the NRC's 2010 performance as a regulator. The UCS said that through the years, it had found the NRC's enforcement of safety rules has not been "timely, consistent, or effective" and it cited 14 "near-misses" at U.S. plants in 2010 alone.[56] Tyson Slocum, an energy expert at Public Citizen said the nuclear industry has "embedded itself in the political establishment" through "reliable friends from George Bush to Barack Obama", that the government "has really just become cheerleaders for the industry."[57]

Although the exception, there have been instances of a revolving door. Jeffrey Merrifield, who was on the NRC from 1997 to 2008 and was appointed by presidents Clinton and Bush, left the NRC to take an executive position at The Shaw Group,[54] which has a nuclear division regulated by the NRC.[note 1]However, most former commissioners return to academia or public service in other agencies.

A year-long Associated Press (AP) investigation showed that the NRC, working with the industry, has relaxed regulations so that aging reactors can remain in operation.[58] The AP found that wear and tear of plants, such as clogged lines, cracked parts, leaky seals, rust and other deterioration resulted in 26 alerts about emerging safety problems and may have been a factor in 113 of the 226 alerts issued by the NRC between 2005 and June 2011.[58] The NRC repeatedly granted the industry permission to delay repairs and problems often grew worse before they were fixed.[58][note 2]

However, a paper by Stanford University economics professors John B. Taylor and Frank A. Wolak compared the financial services and nuclear industries. While acknowledging both are susceptible in principle to regulatory capture, they concluded regulatory failure – including through regulatory capture – has been much more of a problem in the financial industry and even suggested the financial industry create an analog to the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations to reduce regulatory risk.[59]

Office of the Comptroller of the CurrencyEdit

Securities and Exchange CommissionEdit

Similarly in the case of the Allen Stanford Ponzi scheme, there were repeated warnings of fraud from both inside and outside the SEC for more than a decade.[63] But the agency did not stop the fraud until 2009, after the Madoff scandal became public in 2008.

Reporter Matt Taibbi calls the SEC a classic case of regulatory capture[76] and the SEC has been described as an agency that was set up to protect the public from Wall Street, but now protects Wall Street from the public.[77] On August 17, 2011, Taibbi reported that in July 2001, a preliminary fraud investigation against Deutsche Bank was stymied by Richard H. Walker, then SEC enforcement director, who began working as general counsel for Deutsche Bank in October 2001. Darcy Flynn, an SEC lawyer, the whistleblower who exposed this case also revealed that for 20 years, the SEC had been routinely destroying all documents related to thousands of preliminary inquiries that were closed rather than proceeding to formal investigation. The SEC is legally required to keep files for 25 years and destruction is supposed to be done by the National Archives and Records Administration. The lack of files deprives investigators of possible background when investigating cases involving those firms. Documents were destroyed for inquiries into Bernard Madoff, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Citigroup, Bank of America and other major Wall Street firms that played key roles in the 2008 financial crisis. The SEC has since changed its policy on destroying those documents and the SEC investigator general is investigating the matter.[78][79]

Federal Trade CommissionEdit

The decision known as In re Amway Corp., and popularly called Amway '79, made the FTC a captive regulator of the nascent Multi-Level Marketing industry. The situation came to a head in December 2012 when hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management announced an $1 billion short position against the company, and evidently expected the FTC to act, which to date it did not. From a forensic accounting standpoint, there is no difference between a Ponzi-scheme like the Madoff scandal, and a pyramid scheme, except that in the latter the money is laundered through product sales, not investment.[80] The press has widely reported on why the FTC won't act, e.g. Forbes[81] though legal opinion has been very supportive in some quarters, such as Prof. William K. Black, who was instrumental in bringing thousands of criminal prosecutions in the S&L scandal, which was also rife with problems of regulatory capture.[82]

District of Columbia Taxicab CommissionEdit

The District of Columbia Taxicab Commission has been criticized[83] for being beholden to taxi companies and drivers rather than ensuring that the District has access to a "safe, comfortable, efficient and affordable taxicab experience in well-equipped vehicles".[84] In particular, the sedan service Uber has faced impediments from the commission and the city council that have prevented it from competing with taxis.[85]Uber's plan to roll out a less expensive service called UberX was called off after the city council proposed an amendment that would force sedan services to charge at least five times the drop rate of taxis as well as higher time and distance charges, explicitly to prevent Uber from competing with taxis.[86]

Washington State Liquor Control Board and I-502Edit

Some commentators have acknowledged that while Washington State's Initiative I-502 "legalized" marijuana, it did so in a manner that led to a State run monopoly on legal marijuana stores with prices far above that of the existing medical dispensaries,[87] which the State is now trying to close down in favor of the recreational stores, where prices are 2 to 5 times higher than the product can be obtained elsewhere.[88]

Canadian examplesEdit

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications CommissionEdit

Japanese examplesEdit

In Japan, the line may be blurred between the goal of solving a problem and the somewhat different goal of making it look as if the problem is being addressed.[91]

Nuclear and Industrial Safety AgencyEdit

Nuclear opponent[94] Eisaku Sato, governor of Fukushima Prefecture from 1988–2006, said a conflict of interest is responsible for NISA's lack of effectiveness as a watchdog.[92] The agency is under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which encourages the development of Japan's nuclear industry. Inadequate inspections are reviewed by expert panels drawn primarily from academia and rarely challenge the agency.[92] Critics say the main weakness in Japan's nuclear industry is weak oversight.[95] SeismologistTakashi Nakata said, "The regulators just rubber-stamp the utilities' reports."[96]

Both the ministry and the agency have ties with nuclear plant operators, such as Tokyo Electric. Some former ministry officials have been offered lucrative jobs in a practice called amakudari, "descent from heaven".[92][95] A panel responsible for re-writing Japan's nuclear safety rules was dominated by experts and advisers from utility companies, said seismology professor Katsuhiko Ishibashi who quit the panel in protest, saying it was rigged and "unscientific".[95][96] The new guidelines, established in 2006, did not set stringent industry-wide earthquake standards, rather nuclear plant operators were left to do their own inspections to ensure their plants were compliant.[95] In 2008, the NISA found all of Japan's reactors to be in compliance with the new earthquake guidelines.[95]

Yoshihiro Kinugasa helped write Japan's nuclear safety rules, later conducted inspections and still in another position at another date, served on a licensing panel, signing off on inspections.[96]

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW)Edit

Although warned about HIV contamination of blood products imported from the U.S., the ministry abruptly changed its position on heated and unheated blood products from the U.S., protecting the Green Crossand the Japanese pharmaceutical industry, keeping the Japanese market from being inundated with heat-treated blood from the United States.[97] Because the unheated blood was not taken off the market, 400 people died and over 3,000 people were infected with HIV.[97]

No senior officials were indicted and only one lower-level manager was indicted and convicted.[98] Critics say the major task of the ministry is the protection of industry, rather than of the population.[97] In addition, bureaucrats get amakudari jobs at related industries in their field upon retirement, a system which serves to inhibit regulators.[97] Moriyo Kimura, a critic who works at MHLW, says the ministry does not look after the interests of the public.[98]

Philippine examplesEdit

Tobacco control in the Philippines is largely vested in the Inter-Agency Committee on Tobacco (IACT) under Republic Act No. 9211 (Tobacco Regulation Act of 2003).[99] The IACT's membership includes pro-tobacco groups in the Department of Agriculture and National Tobacco Administration,[100] as well as "a representative from the Tobacco Industry to be nominated by the legitimate and recognized associations of the industry," the Philippine Tobacco Institute (composed of the largest local cigarette producers and distributors).[99] In a 2015 Philippine Supreme Court case, the Court ruled that the IACT as the "exclusive authority" in regulating various aspects tobacco control including access restrictions and tobacco advertisement, promotion, and sponsorships. In this case, the Department of Health, which is the primary technical agency for disease control and prevention, was held to be without authority to create tobacco control regulations unless the IACT delegates this function.[101] The IACT's organization also limits the Philippines' enforcement of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.[102]

International examplesEdit

World Trade OrganizationEdit

- Literature

- Other American groups promoting transparency

- ^ Pete Domenici, a former U.S. senator now promotes nuclear energy. Over the course of his 20 years in government, he received $1.25 million in political contributions connected with the energy sector. From 2000 to 2010, the nuclear industry and people who work in it, contributed $4.6 million to members of Congress, in addition to the $54 million spent by electric utilities, trade groups and other supporters to hire lobbyists, including some former members of Congress. (See Eric Lichtblau, "Lobbyists' Long Effort to Revive Nuclear Industry Faces New Test" The New York Times (March 24, 2011)

- ^ According to the AP, of the United States' 104 operating nuclear power plants, 82 are over 25 years old, the NRC has re-licensed 66 for 20 additional years and another 16 renewal applications are under review.

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Regulatory Capture Definition, Investopedia, retrieved October 2, 2015

- ^ a b Timothy B. Lee, "Entangling the Web" The New York Times (August 3, 2006). Retrieved April 1, 2011

- ^ Stigler, George (1915). "The Theory of Economic Regulation" (PDF). Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, (Spring, 1971). pp. 3–21.

- ^ Regulatory Capture 101: Impressionable journalists finally meet George Stigler, Wall Street Journal, October 6, 2014

- ^ Edmund Amann (Ed.), Regulating Development: Evidence from Africa and Latin America Google Books. Edward Elgar Publishing (2006), p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84542-499-2. Retrieved April 14, 2011

- ^ Gary Adams, Sharon Hayes, Stuart Weierter and John Boyd, "Regulatory Capture: Managing the Risk" Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine ICE Australia, International Conferences and Events (PDF) (October 24, 2007). Retrieved April 14, 2011

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander (2013), Small is beautiful, at least in high-income democracies: the distribution of policy-making responsibility, electoral accountability, and incentives for rent extraction [1], World Bank.

- ^ T. Moore, Ryan; T. Giovinazzo, Christopher (5 April 2011). "The Distortion Gap: Policymaking under Federalism and Interest Group Capture". Publius. 42. doi:10.2307/41441079. Retrieved 17 May 2018 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Richter, Wolf (February 21, 2013). "The Military Industrial Complex Is Too Strong Is Too Many States". Retrieved 2017-08-08.

Senate Budget Committee Chairwoman Patty Murray, an "anti-war Democratic senator from Washington State" who "voted against the Iraq war resolution and subsequent troop surges." She's spearheading the Senate's efforts to bring the budget in line. Until it gets to Boeing... "Champion for the Boeing Co.," is how Boeing spokesman Doug Kennett endorsed her during her reelection campaign in 2010.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (February 6, 2017). "As Trump Vows Building Splurge, Famed Traffic Choke Point Offers Warning". Retrieved 2017-08-14.

Millions of people who travel between the Mid-Atlantic and the Midwest each year fight through Breezewood, Pa., a strange gap in the Interstate System... no ramps join [I-70 and the Pennsylvania Turnpike] at their crossing. Instead, drivers travel... blocks with traffic lights and dense bazaar of gas stations, fast-food restaurants and motels... [In order] for a bypass to be considered, essentially Breezewood's own Bedford County must propose it... "It's just not an issue that really appears on the radar for us," said Donald Schwartz, the Bedford County planning director.

- ^ "Thin Political Markets: The Soft Underbelly of Capitalism". cmr.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 17 May2018.

- ^ Jon D. Hanson and David G. Yosifon, The Situation: An Introduction to the Situational Character, Critical Realism, Power Economics, and Deep Capture Abstract at Social Science Research Network. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 152, p. 129 (2003-2004); Santa Clara University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 06-17; Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 08-32. Retrieved April 12, 2011

- ^ Carpenter, Daniel; Moss, David A. (2004). "Preventing Regulatory Capture" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ Engstrom, David Freeman. "Corralling Capture" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Yadin, Sharon (2015). "Too Small to Fail: State Bailouts and Capture by Industry Underdogs". 43 Capital University Law Review 889.

- ^ Stigler, George (1971). "The Theory of Economic Regulation". 2 BELL J. ECON. & MGMT. SCI.

- ^ a b c Thomas Frank, "Obama and 'Regulatory Capture'" The Wall Street Journal (June 24, 2010). Retrieved April 5, 2011

- ^ O'Driscoll, Gerald (12 June 2010). "The Gulf Spill, the Financial Crisis and Government Failure". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Keith B. Hall, "BOEMRE splits -- becomes BSEE and BOEM" Archived 2011-12-11 at the Wayback Machine Oil & Gas Law Brief (October 4, 2011). Retrieved February 17, 2012

- ^ "Salazar Swears-In Michael R. Bromwich to Lead Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement" Archived June 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (June 21, 2010). Retrieved April 8, 2011

- ^ a b c d John M. Broder, "Environmentalists Wary of Obama's Interior Pick" The New York Times(December 17, 2008). Retrieved April 8, 2011

- ^ "2005 "National Environmental Scorecard" Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) League of Conservation Voters

- ^ "2006 National Environmental Scorecard" Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) League of Conservation Voters

- ^ a b c d e f g Ian Urbina, "U.S. Said to Allow Drilling Without Needed Permits" The New York Times(May 13, 2010). Retrieved April 8, 2011

- ^ Lopez, Jaclyn. "BP's Well Evaded Environmental Review: Categorical Exclusion Policy Remains Unchanged." Ecology L. Currents 37 (2010): 1.

- ^ a b Ryan Dezember, "U.S. to Issue More Gulf Drilling Permits" The Wall Street Journal (March 22, 2011). Retrieved April 8, 2011

- ^ a b c d David S. Hilzenrath, "Commodity Futures Trading Commission judge says colleague biased against complainants" The Washington Post (October 19, 2010). Retrieved May 4, 2011

- ^ a b c Barry Estabrook, "How gas drilling contaminates your food" Salon.com (May 18, 2011). Retrieved May 19, 2011

- ^ a b c NYT editorial: "The Halliburton Loophole" The New York Times (November 2, 2009). Retrieved May 19, 2011

- ^ "H.R. 1084: Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act of 2011" govtrack.us Retrieved May 19, 2011

- ^ "S. 1215: Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals (FRAC) Act" govtrack.us Retrieved May 19, 2011

- ^ a b c Paul Lowe, "Bill proposes distance between airlines and FAA regulators" AINonline.com (September 1, 2008). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ a b c Johanna Neuman, "FAA's 'culture of coziness' targeted in airline safety hearing" Los Angeles Times (April 3, 2008). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ Library of Congress, Thomas Official Website Bill Summary & Status 110th Congress (2007 - 2008) H.R.6493

- ^ Library of Congress, Thomas Official Website Bill Summary & Status 110th Congress (2007 - 2008) S.3440

- ^ David Koenig, "Southwest Airlines faces $10.2 million fine" Mail Tribune, Associated Press (March 6, 2008). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ John Hughes for Bloomberg News. March 2, 2009. Southwest Air Agrees to $7.5 Million Fine, FAA Says (Update2)

- ^ "FAA will stop calling airlines 'customers'" Reuters, USA Today (September 18, 2009). Retrieved October 17, 2009

- ^ Roger A. Arnold, Economics Google Books. Thomson South-Western, 8th edition (2008) p. 497. ISBN 978-0-324-53801-4. Retrieved April 12, 2011

- ^ Lori Alden, "Why are some firms more profitable than others?" econoclass.com (2007). Retrieved April 12, 2011

- ^ Steven M. Davidoff, "The Government's Elite and Regulatory Capture" The New York Times (June 11, 2010). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ Travis, Hannibal (2007). "Of Blogs, eBooks, and Broadband: Access to Digital Media as a First Amendment Right". Hofstra Law Review, Vol. 35, p. 148. President and Trustees of Hofstra University in Long Island, New York, quoting Peter H. Shuck, The Politics of Regulation, 90 YALE L.J. 702, 707-10 (1981) (book review). SSRN 1025474.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal (2007). "Of Blogs, eBooks, and Broadband: Access to Digital Media as a First Amendment Right". Hofstra Law Review, Vol. 35, p. 152. President and Trustees of Hofstra University in Long Island, New York, citing Red Lion Broad. Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367, 389, 396 (1969). SSRN 1025474.

- ^ "Regulatory Capture in Action" Robert Paterson, blog (March 15, 2011). Retrieved April 12, 2011

- ^ a b c Edward Wyatt, "F.C.C. Commissioner Leaving to Join Comcast" The New York Times (May 11, 2011). Retrieved May 12, 2011

- ^ Kushnick, Bruce (July 10, 2017). "Regulatory Capture of the FCC: Stacking the Deck with the New Proposed Republican Commissioner". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Jo Becker and Gretchen Morgenson, "Geithner, Member and Overseer of Finance Club" The New York Times (April 26, 2009). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ a b c d e David Reilly, "Secret Banking Cabal Emerges From AIG Shadows" Bloomberg (January 29, 2010). Retrieved April 11, 2011

- ^ Eric King, Part II, Interview with Jim Rickards Archived 2011-03-03 at the Wayback Machine King World News (December 7, 2010). Retrieved May 14, 2011

- ^ Katie McCabe (15 May 2011). "Making History in a Segregated Washington: By Dovey Johnson Roundtree and her 45 year Fight for Justice" (PDF). XLII (I). Journal of the Bar Association of the District of Columbia: 84. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2012.

- ^ http://www.thecapitalnews.com/building-the-beloved-community-the-roundtree-residences

- ^ Frank Von Hippel (March 23, 2011). "It Could Happen Here". New York Times.

- ^ Justin Elliott, "Ex-regulator flacking for pro-nuke lobby" Salon.com (March 17, 2011). Retrieved March 18, 2011

- ^ a b c d e Kate Sheppard, "Is the Government's Nuclear Regulator Up to the Job?" Mother Jones(March 17, 2011). Retrieved March 18, 2011

- ^ "Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Station-License Renewal" NRC, official website. Retrieved April 04, 2011

- ^ Jia Lynn Yang, "Democrats step up pressure on nuclear regulators over disaster preparedness" The Washington Post (March 18, 2011). Retrieved March 19, 2011

- ^ Eric Lichtblau, "Lobbyists' Long Effort to Revive Nuclear Industry Faces New Test" The New York Times (March 24, 2011). Retrieved March 25, 2011

- ^ a b c Jeff Donn, "U.S. nuclear regulators weaken safety rules" Salon.com (June 20, 2011). Retrieved June 20, 2011

- ^ http://web.stanford.edu/~johntayl/Drell-Shultz_NuclearEnterprise_ch13.pdf

- ^ Joe Nocera, "An Advocate Who Scares Republicans" The New York Times (March 18, 2011). Retrieved March 19, 2011

- ^ Matt Taibbi, "Why Isn't Wall Street in Jail?" Rolling Stone (February 16, 2011). Retrieved March 3, 2011

- ^ "Madoff Whistleblower Markopolos Blasts SEC" Bloomberg News (June 5, 2009). Retrieved March 29, 2011

- ^ Chidem Kurdas "Political Sticky Wicket: The Untouchable Ponzi Scheme of Allen Stanford"

- ^ "Gary J. Aguirre v. Securities and Exchange Commission, Civil Action No. 06-1260 (ESH)" United States District Court for the District of Columbia (April 28, 2008). Google Scholar. Retrieved March 1, 2011

- ^ a b "Pequot Capital and Its Chief Agree to Settle S.E.C. Suit for $28 Million" The New York Times(May 27, 2010). Retrieved March 4, 2011

- ^ a b "SEC Settles with Aguirre" Government Accountability Project (June 29, 2010) Retrieved February 21, 2011

- ^ "SEC Charges Pequot Capital Management and CEO Arthur Samberg With Insider Trading" U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission press release (May 27, 2010). Retrieved March 3, 2011

- ^ Gretchen Morgenson, "SEC Settles With a Former Lawyer" The New York Times (June 29, 2010). Retrieved February 21, 2011

- ^ "Robert Khuzami Named SEC Director of Enforcement" U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Press Release (February 19, 2009) Retrieved January 9, 2011

- ^ Kara Scannell, "Davis Polk Recruits Ex-SEC Aide" The Wall Street Journal (April 13, 2009) Retrieved February 26, 2011

- ^ "Deutsche Bank Hires Former S.E.C. Official" The New York Times (October 2, 2001). Retrieved March 4, 2011

- ^ Reed Abelson, "Gary Lynch, Defender of Companies, Has His Critics" The New York Times(September 3, 1996). Retrieved March 4, 2011

- ^ Walt Bogdanich and Gretchen Morgenson, "S.E.C. Inquiry on Hedge Fund Draws Scrutiny" The New York Times (October 22, 2006) Retrieved March 4, 2011

- ^ a b Suzanne Barlyn, "DJ Compliance Watch: SEC Plan To Catch Big Fish Questioned" Dow Jones Newswire (May 16, 2011). Retrieved May 23, 2011

- ^ a b "Revolving Regulators: SEC Faces Ethic Challenges with Revolving Door" Project on Government Oversight (May 13, 2011). Retrieved May 23, 2011

- ^ Matt Taibbi interviewed on his article, "Why isn't Wall Street in jail?" Democracy Now! Video and transcript. (February 22, 2011). Retrieved March 4, 2011

- ^ Don Bauder, "Gary Aguirre Major Source in Taibbi Blockbuster" San Diego Reader blog post (February 17, 2011). Retrieved February 19, 2011

- ^ Matt Taibbi, "Is the SEC Covering Up Wall Street Crimes?" Rolling Stone (August 17, 2011). Retrieved August 19, 2011

- ^ Edward Wyatt, "S.E.C. Files Were Illegally Destroyed, Lawyer Says" The New York Times (August 17, 2011). Retrieved August 19, 2011

- ^ "Pyramid Schemes & MLM – Fraud Files Forensic Accounting Blog". www.sequenceinc.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Stroud, Matt. "Why The FTC Won't Take Bill Ackman's Advice To Prosecute Herbalife (Even Though It Should)". Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "OPINION: Thinking outside the pyramid". Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Marc Fisher, "D.C. Taxis--No Zones, No Justice?" The Washington Post (April 23, 2008). Retrieved July 9, 2012

- ^ "About the DC Taxicab Commission" Archived 2012-06-17 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 9, 2012

- ^ Eric Eldon, "The DC Taxi Commissioner's Attacks On Uber Have Gotten Even More Ridiculous"Tech Crunch (January 14, 2012). Retrieved July 9, 2012

- ^ Eric Eldon, "DC City Council's "Uber Amendment" Would Force Sedans To Charge 5x Taxi Prices (And Kill UberX)" Tech Crunch (July 9, 2012). Retrieved July 9, 2012

- ^ http://www.thenewstribune.com/2014/11/21/3501411_unchecked-pot-dispensaries-are.html?sp=/99/447/&rh=1 Archived 2015-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Washington now has the worst recreational marijuana law". 5 November 2014. Retrieved 17 May2018.

- ^ "CRTC wants internet pricing answers from Bell" CBC News (August 24, 2009). Retrieved April 5, 2011

- ^ "CRTC Chair Defends UBB Decision at Industry Committee Meeting amidst Backlash"OpenMedia.ca (February 3, 2011). Retrieved April 4, 2011

- ^ Nakamura, Karen. "Resistance and Co-optation: the Japanese Federation of the Deaf and its Relations with State Power," Social Science Japan Journal, Vol. 5, No. 1 (April 2002), p 19 (PDF 3 of 20).

- ^ a b c d Hiroko Tabuchi, Norimitsu Onishi and Ken Belson, "Japan Extended Reactor's Life, Despite Warning" The New York Times (March 21, 2011). Retrieved March 22, 2011

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-01-19. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ "Comments by Fukushima Prefecture Governor Eisaku Sato Concerning Japan's Pluthermal (MOX fuel utilization) Program and the Nuclear Fuel Cycle" Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback MachineGreen Action (June 4–5, 2002). Retrieved March 22, 2011

- ^ a b c d e Norimitsu Onishi and Martin Fackler, "Japanese Officials Ignored or Concealed Dangers"The New York Times (May 16, 2011). Retrieved May 17, 2011

- ^ a b c Jason Clenfield and Shigeru Sato, "Japan Nuclear Energy Drive Compromised by Conflicts of Interest" Bloomberg News (December 12, 2007). Retrieved March 22, 2011

- ^ a b c d e Masao Miyamoto, "Mental Castration, the HIV Scandal, and the Japanese Bureaucracy"Japan Policy Research Institute (August 1996). Retrieved April 1, 2011

- ^ a b Tomoko Otake, "Ministry insider speaks out" Japan Times (November 1, 2009). Retrieved April 1, 2011

- ^ a b "Tobacco Regulation Act of 2003".

- ^ "National Tobacco Administration".

- ^ Philippine Supreme Court. "Department of Health v. Philip Morris Manufacturing (2015)". Archived from the original on 2017-07-04.

- ^ Roque, Harry. "House Bill No. 917 (17th Congress)" (PDF).

- ^ Thomas A. Faunce, Warwick Neville and Anton Wasson, "Non Violation Nullification of Benefit Claims: Opportunities and Dilemmas in a Rule-Based WTO Dispute Settlement System" (PDF) Peace Palace Library. In M. Bray (Ed.), Ten Years of WTO Dispute Settlement: Australian Perspectives. Office of Trade Negotiations of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved April 17, 2011

BibliographyEdit

- Bernstein, M. 1955. Regulating Business by Independent Commission. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Glover, P. 2007. "A Crime Not a Crisis: Why Health Insurance Costs So Much"'.

- Huntington, S. 1952. The Marasmus of the ICC: The Commission, the Railroads, and the Public Interest. Yale Law Journal 614:467-509.

- Laffont, J. J., & Tirole, J. 1991. The politics of government decision making. A theory of regulatory capture. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106(4): 1089-1127

- Lee, Timothy B. (August 3, 2006). "Entangling the Web". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- Levine, M. E., & Forrence, J. L. 1990. Regulatory capture, public interest, and the public agenda. Toward a synthesis. Journal of Law Economics & Organization 6: 167-198

- Stigler, G. 1971. The theory of economic regulation. Bell J. Econ. Man. Sci. 2:3-21.

External linksEdit

ーーー

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

原発事故から5年。続々進む再稼働。日本人はフクシマから何を学んだのか? 国会事故調元委員長が、規制する側(監督官庁)が規制される側(東電)の論理に取り込まれて無 ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

このように、規制する側が規制される側に取り込まれて、規制が規制される側に都合よく歪曲されるメカニズムを「規制の虜」という。ノーベル賞経済学者ジョージ・スティグラーが唱えた理論だ。もっとも日本では「官民の癒着」というのはよく見られる構図だ。規制者 ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?isbn...

規制の英雄たちと規制の虜の問題釣りに対する政府保護は、なにかおかしくなったら訴訟できるような契約法だけではない。規制もある。アメリカ初の大きな規制機関は、 1887年に創設された州際通商委員会(1CC)で、地元の人々を鉄道による収奪的な値づけの ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

その時点で「認識の虜」になり、互いの視点で物事を見るようになります。これが「規制の 虜」につながり、規制当局が規制すべき相手寄りの考え方をするようになったり、相手に支配されるようになります。回転ドア人事により、さらに 的に考え、問題の部分を ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?isbn...

が情報の非対称性などを利用して、「規制する側」を取り込んでいくことを示す概念である。政府の規制官庁が業界に取り込まれ、規制を作っても骨抜きになったり、業界の利益誘導の片棒を担いだりするようになる。情報の非対称による、いわゆる「政府の失敗」で ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?isbn...

Barth et al.(2012)は,銀行業の“規制の虜”を議論するうえでこの類推を使っている.その参考文献も参照. ☆60.この洞察を最初に行ったのは Olson(1965), Stigler(1971), Peltzman(1976)である.Center for Responsive Politicsによると(情報は以下で入手可能.

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

の拡大を招いた事故後の対応状況を紐解く中で、これまで断片的には語られあるいは一般論としては批判されていた三・一一以前の長年にわたる規制の虜と言われる事業者と規制当局側の関係、緊急時に機能しない官僚制度上の問題、あるいは民間において ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

但し重要資材使用制限規則の違反は同規則の虜理方針によることとなつている。 ... 物資、獲掘物資及び資とは異り、物資の生産業者又は販資業者の所有する常該物資にういては、それぞれ常該物資の割常配給に闘する他の法令によつて規制せられて居り。

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

規制の虜状祝は日本における金馳規制と規制緩和の多くを特微づけてきた。規制緩和は、大抵は、最初に元の規制を求めたのと同一の利益(集団)の要望に対する反応であった。金馳機関が活動する経済的撮境の変化によって、これらの機関は大蔵省の手の ...

https://books.google.co.jp/books?id...

経済はむずかしい。簡単に理解できる本はないだろうか。 こんなことが言われるのは、日本だけではないのですね。アメリカでもしばしば聞かれる声だそうです。では、それに ...

ーーー

スティグラ ーは 、従来の産業組織論 (ハーヴァードに E ・ H ・チェンバリン 、 R ・ケイヴズ 、エドワ ード ・メイスンのような中心的な学者がいたので 、 「ハーヴァード学派 」と呼ばれることが多い )が 「独占 」 「寡占 」 「自然独占 」などの 「市場構造 」に注目して 、 「経済的厚生 」の改善のために規制を正当化してきたのに対して 、規制とは 、 「業界によって獲得され 、主としてその利益に適うように設計され運営される ( * 9 ) 」という新しい理論を提示した (規制によってその産業への新規参入が困難になれば 、既存の企業はその分超過利潤を獲得することが可能であることに注意 。このような考え方は 、いまでは周知のものになったが 、 「政治過程の経済分析 」と密接な関連性をもっている ) 。スティグラ ーは 、次のように述べている ( * 1 0 ) 。

「規制を求める産業は 、政党が必要とする二つのもの 、すなわち票と資金をもってその代価を支払う用意がなければならない 。資金は 、政治活動資金の寄付 、(実業家が 、選挙資金調達委員会の責任者となるといったような )奉仕活動や 、政党の職員を雇用するといったようなもっと間接的な方法などによって提供することが可能である 。当該産業や他の関連業界の構成員を教育したり (あるいは反教育したり )するような金のかかる企画によって 、規制に対する支持票は結集され 、反対票は駆逐される 。 」

* 9 … … G ・ J ・スティグラ ー 『小さな政府の経済学 ─ ─規制と競争 』余語将尊 、宇佐見泰生訳 (東洋経済新報社 、一九八一年 )一七九ペ ージ 。引用は 、 「経済規制の理論 」から 。

* 1 0 … …前同 、一九八ペ ージ 。