ライプニッツ 1663年

「個体化の原理についての形而上学的討論」(

ラテン語/英語)

(

Disputatio metaphysica de principio individui/

Metaphysical Disputation on the Principle of Individuation)

Leibniz(1646-1716) 1663

参照:

Leibniz on Individuals and Individuation: The Persistence of Premodern Ideas in Modern Philosophy

(

http://www.amazon.com/dp/0792338642)

ラテン語原典は Gerhard版の著作集第4巻に所収、

ドイツ語の解説付きの版(1837年)がPDFで公開されている。

http://books.google.com/books?id=rXj2C8L9gMAC&hl=jaなお、J. Quillet によるフランス語訳と註解が雑誌 "Les etudes Philosophiques" 1979年、1号年、1号、79-105頁

に掲載されている。

(

http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=12642830)

以下、『ライプニッツ哲学研究 』(山本信 著)133〜5頁より、ライプニッツ論考の要約。

第二節 個体性

ライプニッツの最初の作品は、『個体の原理についての形而上学的討論』(Disputatio metaphysica de principio indi‐

vidui.1663)(GIv15-26)であった。この論文の中で彼は中世スコラ以来の問題、個体化の原理(principium individua‐

tionis)を取扱い、四つの代表的な意見をあげて、博識と技巧とを示しつつ、一つを弁護し三つを論駁してゐる。その

論ずるところによれば、個体化の原理は一般者或いは普遍者の否定的限定(negatio)でもなく、本質或いは形相に結

合されてそれを固定するところの外的なものとしての存在或は質料(existentia, materia)でもなく、haecceitas 即

ち、種の類に対する如く種に対して付加されるところの、それ自身形相たる個体差或いは質料(differentia individuifi‐

ca, numerica)でもない。個体はそれ自身において積極的肯定的なもの(ens positivum)であり、

「すべての個体はそれ

の存在性全体によって個体化される」(omne indiviiduum sua tola entitate individuatur)、云々。唯名論的立場からする

個体そのものの積極性の主張が、明らかに看取される。尤も、ここでライプニッツが弁護し主張しようとしている提

説は、他の諸説に対する論駁の鮮かさに比して甚だ曖昧である。しかしながらこれは、唯名論的立場にとってはむし

ろ当然のことである。個体化の原理が本来的に問題とされるのは、普遍者に何らかの意味で優先性と実在性とを帰す

る立場からである。従って、現実に存在するものは既に個体であるとする立場においては、個体化ということが、少

くとも昔ながらの形では、問題になり得ない。即ちそこで問題なのは、「個体化の」ではなくて、まさに題名の示す

通り「個体」の原理であり、個体そのものの内容的分析解明である。そしてこれが展開され仕上げられて後期の個体

論に至った、と見ることができるであろう。

さてライプニッツによれば、実体は究極的主語として、その実体について言われ得るあらゆる述語を含むところの

概念を有するのであった(一一三〜四頁参照)。かかる「完全な概念」によって、実体は常に一個の個体に決定されてい

るのである(determine a un individu, Glv435b)。この完全概念即ち個体的概念が含む述語の数は絶対的に無限でなけ

ればならない。その数が無限でない場合には、それらの述語が内在する主語は充分個体に決定されていない。「有限

数の述語を幾ら取ったところで、残りのすべてを決定することができないから同じことである。一定の一人のアダム

を決定するものは、そのすべての述語を絶対的に含んでいなければならない。一般性を決定して個体となすのは、こ

の完全概念である」(Gll54b)。種や偶有性の概念においては事物の一般的抽象的本質が考へられるだけであるのに対

し、個体の概念の中にはそのもののあらゆる個別的具体的状態が含まれており、その連鎖を辿ってゆけば宇宙の全系

列が含まれるに至る(Gll39b,277c‐8a,lv433b,vll311b)。「個体性は無限を含む」(G v268b)のである。

宇宙全体との関係におけるこれらの無数の述語は、その実体にとって単に外的な規定なのではない。ライプニッツ

によれば、外的規定には必ず内的規定が対応している(Gv211a,vll311b)。従って、各実体が無数の述語によって個

回に決定されているといふことは、それぞれ内容的に他から区別されていることにほかならない。二つの実体が全く

相等しくて、ただ数においてのみ異なる、ということはあり得ず、そこには必す内的規定に基づく差異が存するので

ある(Glv433c,v100a,213b,vl608b, vll395a)。この点に関しライプニッツは、好んでトマス・アクィナスの天使論を

引合いに出している。周知のやうに、トマスによれば、質料と形相とからなる合成実体の個体化の原理は、いわゆる

「指示された質料」(materia signata)であるが、単純実体即ち質料をもたぬ叡智体である天使については、これは妥

当しない。天使はその各々が最低種なのであって、合成実体における如く種においては同一で数において異なる、と

いふことはなく、個体があるだけ種が存するのである。ところがライプニッツは、この天使について言はれたことが

すべての実体に当て嵌まると主張する。即ち、その概念の中にそれ自身で説明され得る差異を有するものは、種におい

て異なると言われるが、まさにすべての個体的実体はその概念自身において、従って「種において」、異なっている

のである(Gll42b,54c,131c-2a, vll433c)。そこで今度は逆に、もし全く相等しい規定をもち、如何なる点でも相互

に識別され得ぬ二つのものを考へるならば、この二つは実際には一にして同じものであって、ただ同一のものを二つ

の名で呼んでいるにすぎない、といふことになる。幾何学において対象を先づ二つと仮定しておき、次に実はそれが

一つであることを示すやり方、これと同じ事情がここにも存するのである(GMI372b,395c)。かくしてライプニッツの

実体論は、かの処女論文における個体の積極性の主張と結びつく。各々の実体は、それ自身の内容の充実と具体性と

において、他のすべてのものから区別された個体性を有する、即ち、「それの存在性全体によって個体化される」の

である。このこと以外に「個体化の原理」は存しない(Gv214a)。

〜〜〜〜〜〜以下本文〜〜〜〜〜〜

CUM DEO

1.

Quanto latius argumentum nostrum diffusum est, verba vero pauciora esse debent, tanto magis abstinendum nobis a praefatione esset, nisi admoneret Divino Numini debita invocatio. Deum igitur ptimum Actum Fontemque secundorum oramus obtestamurque,ut cujus in re ipsa causa est, ejus quoque in nostra cognitione suscitator esse velit, ne quicquam cuiquam,nisi ipsi bonitatis debeamus.

WITH GOD

1.

We should be brief,as the more extended is our argument,the more we should refrain from a preface,except for an invocation owed to the Divine Spirit.Therefore,we pray and supplicate God, the first act and origin of secondary acts,that of which he is the cause in reality,of the same also will he be the source in our thought so that we will owe him whatever of worth our endeavor produces.

2.

Ante omnia autem statum quaestionis excutiemus.

Acturi igitur sumus de principio individui, ubi et principium et individnum varie accipitur. Et quod ad Individuum attinet, quemadmodum universale, sie ipsum quoque vel logicum est in ordine ad praedicationem, vel metaphysicum in ordine ad retn. Atque sic rursum aut prout in re est, aut, prout in concepto, seu, ut alii exprimunt, formaliter aut fundamentaliter.

Et formaliter vel de individuo omni, vel creato tantum, vel substantia tantum, vel substantia materiali.

Principü quoque vox notat tum cognoscendi principium,

tum essendi. Essendi internum et externum.

Quare, ut haec colligam: agemus de aliquo reali et, ut loquuntur, principio physico, quod rationis individui fonnalis, seu individuationis, seu differentiae numericae in intellectu sit fundamentum, idque in individuis praecipue creatis,substantialibus.

2.

To begin with,we will examine the state of the question.We are,then,to treat of the principle of the individual.Now both ‘principle' and ‘individual ’are understood in various ways. Speaking of ‘individual',we note,on the one hand,that,like‘universal',it has either a logical sense−with regard to predication−or it has a metaphysical sense−with regard to the thing.On the other hand,we note that ‘individual' may mean "according to the thing”(in re),or "according to the concept"(in conceptu),or as some say,respectively,"fundamentally"or"formally." Formally,'individual' is understood in terms of every individual,or in terms of only created substances,or in terms of substance,or in terms of just material substance.Too,‘principle’is used to mean the principle of knowing and of being.There are internal and external senses of the principle of being. Wherefore,to summarize the foregoing,we treat of some thing real and what is called a “physical principle,” which would serve as the foundation for the formal notion in the mind of ‘individual’,understood either as individuation or numerical difference.We shall address individuals,especially created and substantial individuals [ i.e.,both material and non−material finite substance.See Section 3.]

3.

Quia vero, ut attritu silicis scintillae emicant, ita commissione sententiarum veritas detegitur, age primum eas digeremus. Sunt autem duo genera opinionum: alii hypotheses habuere ad omnia individua applicabiles, ut Scotus, aUi secus, ut Thomas, qui in corpotibus materiam signatam, in Angelis eorum entitatem principium posait. Nos quoniam hic abstrahe-

mus a substantia materiali et immateriali, speciales opiniones alio tempore consideraturi, nunc generales tantum excutiemus. Quas praecipue quatuor numerare licet. Aut enim principium individuationis ponitur Entitas tota (1) aut non tota. Non totam aut negatio exprimit (2), aut aliquid positivum; hoc aut pars physica est, essentiam terminans, existentia (3), aut metaphysica, speciem terminans, haecceitas (4).

3.

However,let us first set the various kinds of views in order,since truth is discovered by setting opinions off against each other,Just as sparks fly when the flint is struck.There are,then,two kinds of opinions.Some, like Scotus,have held hypotheses that were applicable to all individuals. Other, like Thomas,held a different view.He maintained that the principle in bodies was signate matter and in angels their entity.Since we shall here abstract from material and non−material substance−with special opinions to be taken up at another time, we shall examine only the general opinions. We may list four main views.The principle of individuation is taken to be either the whole entity(1),or not the whole entity.Less−than−whole entity is expressed either by negation(2),or by something positive. Concerning the positive sense of less−than−whole entity,One may take one of two views:(3)there is a physical part of the individual that terminates its essence,existence;Or(4)a metaphysical part that terminates species, haecceity.

4.

Prima opinio, quoniam et a gravissimis viris defenditur et difficultates omnes tollit, a nobis quoque recipietur, cuius confirmatio velut generale argumentum contra reliquas suppeditabit.

Pono igitur: omne individuum sua tota entílate individuatur. Et tenet Petrus Aureolus apud Johannem Capreolum, qui eum n'ondum editum diligenter confutavit, 2. sent. d. 3. q. 2. Hervaeus, quodlib. 3.q. 9. Dicitque Soncinas, quod haec opinio sit Terministarum ministarum seu Nominalium, 7. Met. q. 31. Et tenent sane Gregor. Ariminensis 1. sent d. 17. q. 4.Gabriel Biel in 2. sent. d. 3. q. 1. Quos adducit

recentior Nominalis Schautheet 1. 2. Contr.5.artic. 1. Tenet idem Durandus 2. d. 3. q. 2., citantibus sic plerisque, quamvis, ut notat Murcia, disp. 7.in 1. l.i Physic. Ar. q. 1., citari soleat pro sola forma, quum tamen n. 15. expresse hanc materiam et hanc for- mam afferat. Male autem Ramon e da eos, qui dicunt, individuum se ipsum individuare, et qui dicunt, materiam et formam id praestare, divellit, ut sibi contradistin- ctos, quum sint potius subordinad, ut speciales genera- libus. Quid enim est materia et forma unitae, nisi tota entitas compositi? Adde quod nos hic abstrahi- mus a corporibus et Angelis; potius igitur termino to- tius entitatis, quam materiae et formae utimur. Idem igitur tenet Fr. Murcia, 1. с. Fr. Suarez, disp. Met. 5. Zimara apud Mercenar. disp. de. P. I. P. 1. c. 9. Perer. 1. 6. c. 12. Ac nuperrime PI. Reverend. Calov. Met. Part. Spec. tr. 1. art. 1. c. 3. n. 2. et B. Stahl. Сотр. Met. c. 35.

4.

The first opinion,because it is held by the most distinguished men and

removes all difficulties [that pertain to the rejected candidates],will be adopted by us,the confirmation of which furnishes,as it were,a general argument against the remaining views.Therefore,I maintain:every individual is individuated by its whole entity. And this is held by Petrus Aureolus,according to Johannes Capreolus,Who carefully refutes Capreous before he was even publisbed(in 2 Sent.,d.3,q.2).See also Hervaeus(quodlibet 3,q.9). And Socinas says that this would be the position of the terminists or nominalists(in 7 Meta.,q.31).And Gregorius Admenensis(in 1Sent.,d.17,q.4)and Gabdel Biel(in 2 Sent.,d.3,q.1)hold the same view and the nominalist Schauteet has just recently(in L.2.,Contr.5,art.1)presented their views. The same position is held by Durandus(2 Sent.,d.3,q.2)and is so referred to by many,although,

as Murcia notes(Disp.7,in 1 Physic.Ar.q.1), Durandus is usually cited as holding this view with respect to form alone,When he clearly states it to be this matter and this form. However,Ramoneda erroneously attacks those who claim that the individual individuates itself and those who say that matter and form supply it [ the principle of individuation], as contradicting each other,since they could instead be understood to be subordinate views,as special instances under the general view. For what is matter and form united except the whole entity of the composit? Add we here abstract from bodily substances and angels,so that we preferably employ the term, 'whole entity',rather than‘matter and form'. The same position is maintained by Murcia (loc.cit.), Suarez(Dis.m.5), Zimare, according to Mercenarius(in Dis. de P.I.,Pars 1,c.9), and Pererius(L.6,c.12). And just recently PL.Rev.Calov(Met. Divina,Pars Spec.,tr.1,c.3,n.2)and D.Stahl(Com.Met.,c.35)have advocated this view.

5.

Argumenta pro hac sententia haec fere sunt. 1) Per quod quid est, per id unum numero est. Sed res quae- libet per suam entitatem est: E. Maior probatur, quia unum supra ens nihil addit reale. Usi sunt hoc argumento omnes hujus sententiae defensores. Res- pondet Bassolius Scotista negando majorem: ac dicit, naturam seu entitatem rei differre formaliter,

non realiter. Et sic limitat: per quod quid est, per idem realiter ntmm numero est. Et sic conceditur; si per idem formatter, negutur. Et ad probationem dicere potest, quod unum aliquid supra ens addat tonuuliter diversum. Sed haec protligabuntur inf'ra in reiutatione Scoti.

5.

The arguments for this position are usually the following:

1.That by means of which something is,by means of it that some thing is one in number. But any thing is by means of its entity.Therefore,[any thing is one in number by reason of its entity]. The major is proved in that one adds nothing real beyond being. All who defend this position use this argument. Bassolis,the Scotist, replies by denying the major. He says that nature or entity of the differ fotmally, but not really.And so he qualifies[the major premise]: That by means of which something is, by means of it that something is really one in number,he allows.[That by means of which something is,]by means of it that something is formally one in number,he denies. And,in proof of this he can say that one adds something beyond being formally distinct from it it. But this position will be utterly refuted below in the refutation of Scotus.

6.

Mercenarius negat majorem, et ad probationem dicit, non quidem unum specie, sed tamen unum

numero addere aliquid supra ens. Sed contra: id quod addit, quum sit aliquid reale, erit ipsum quoque ens. E. addet aliquid supra se ipsum. Si vero dicat, non loqui se de omni ente, quod etiam modos includat, urgeo: id, supra quod unitas numerica aliquid addit, est ens. Si igitur est unum

numero, praecisum ab addito, nihil addit unitas numerica;

sin minus, dabitur quoddam ens reale, quod non sit singulare, de quo infra. Taceo, quod Mercenarius more Scotistico respondit, quum faveat Thomae.

6.

Mercenadus denies the major and in his proof says that,indeed,not the one inspecies but,instead,the one in number adds something beyond being. But,to the contrary: that which adds,since it is something real, will itself also be being.Therefore,it will add something beyond itself. But,if he were to say that he was not speaking of all being,which would also include modes,I argue:that beyond which numerical unity adds something is being.Therefore,if the one in number is separate from what is added,numerical unity adds nothing;if, to the contrary,it is not separate,there would be some real being,Which would not be singular,concerning which see below. I say nothing about what Mercenadus responds along Scotistic lines,since he favors Thomas.

7. (1)

Ramoneda respondet: ntmm et ens formaliter diflerre, quamvis materialiter sint idem. Pro тш formaliter intelligit: diflerre ratione. E. etiam principia ntdus numero et entis, ratione differant. Soncinas ait, Arist. IV. Met. 2, unde hoc argumentum sumat, пол loqui de unitate numerali, sed transcendentali.

Verum et ilia est transcendens, et non datur unitas realis speciei, praeter numeralem. Posset quoque aliquis pro omnibus sententiis adVersis, ex eo fundamento,

quo a nobis differunt, respondere, fieri tmum numero per snam entitatem, sed цод totam. Yerum obstat,

quod altera quoque pars intrinsece est una riumero, et sequeretur, si principia interna unius et entas differunt, ut totum et pars, unum et ens quoque, ut totum et partem differre, immo ens aliquid addere supra unum. Atque haec de hoc argumento fusius, ut melius videatur, quae quisque effugia quaerat.

7. (2)

Quae sunt principia entis in universali universalia, ea sunt ejus principia in singular! singularia. Sed tota entitas est principium entis universale in universali :

E. Major probatur probabiliter ab analogía.

2.Quia principia universalia nullo alio differant a singulari, nisi quod a multis singularibus similibus abstrahuntur. Est hoc argumentum Stahlii.

3. Durandus: universale et singulare non differant realiter. E. habent eadem principia. E. entitas tota, quae est principium universalitatis, est singularitatis.

7.

Ramoneda answers:one and being differ formally, although materially they are the same. By 'formally', he understands them to differ mentally.

Therefore,the principle of one in number and of being differ mentally.

Socinas says that Aristotle(in lV Meta.2,whence this argument is taken)means not numerical unity,but transcendental unity.But the former is transcendent and there is no real unity of a species except numerical unity.

One could also respond on behalf of all who oppose this position on the basis of the grounds by reason of which they differ from us:something becomes one in number by means of its entity, but not its whole entity. But there is opposed to this[claim] the fact that the other part [ viz.,nature] is also intrinsically one in number and it would follow that, if the internal principles of one and of being differ as whole and part. One and being also differ as whole and part. Therefore being adds something beyond one.

And we have dealt with this argument at some length,in order to see more clearly the escape routes[from attack ] that each variation seeks.

2.Those which are universal principles of being in the universal are the singular principles of being in the singular. But,whole entity is the universal principle of being in the universal. Therefore.[ whole entity is the singular principle of being in the singular].The major is proved probably by analogy 2, in that the universal principles do not differ from the singular except in that the universal principles are abstracted from many similar singulars. This is the argument of Stahlius.

3.Durandus argues:the universal and the singular do not differ really. Therefore,they have the same principles. Therefore, whole entity,which is the principle of universality,will be the principle of singularity.

8.

4) Datur v. g. in Socrate natura intrinsece ad ipsum determinate, quod concedit Soncinas, extra. intellectum, et si negaret, daretur contra Thomistas universale completum in rebus. Immo etiam dicit Bassolius Scotista, quod detur solum in re universale in potentia, nempe natura singularis in respecta ad intellectum, qui cum similibus comparari potest. Ulterius daturne etiam natura indifferons in Socrate?

Si nulla, jam patet, quod se ipsum individuet natura Socratis; sin aliqua dabitur, simal differens et indifferons natura humana in Socrate. Nec effugit Soncinas dicens, quod differens et indifferens differat rat ratione. Nam sic patet, quod natura sit determinata in re per se ipsam, non per aliquid additum.

8.

4.There is a nature, for example, in Socrates, which is intrinsically determined outside the mind to him, which Socinas grants. If he were to deny this,there would be−contra the Thomists−a complete universal in things. Indeed, the Scotist, Bassolis, also says that there would be in the thing only a potential universal, namely a nature slngular in respect to the intellect which can compare it with similar natures. Is there not, in addition, in Socrates a nature indiffrent [to detemination]? If there is none, then it is now plain that the nature of Socrates individuates itself;if, to the contrary, there is some such nature, there will be at the same time in Socrates a different[i.e.,determinate] and indifferent[i.e.,deteminate] human nature. Socinas does not escape[this objection]in] in saying that different and indifferent differ mentally. For it is then plain that nature would be detemined in itself and by means of itself and not by something added.

9.

5. Essentía aliqua, humanitas v. g. Socratis, aut diifert numero ab humanitate Platonis intrinsece, si nempe praescindam id, quod naturae extra ipsam superadditum est, aut non. Si differt numero intrinsece,individuat se ipsam. Sin minus, sequitur, quod in se humanitas Platonis et Socratis sint idem numero, et uti natura cum alia natura, ita posset quoque cum addito comparan. Sed nunc mitto.

9.

5.An essence, the humanity of Socrates for example, either intrinsically differs in number from the humanity of Plato - if, that is, we put aside that which is added to nature beyond nature, or it does not [ so differ].

If it intrinsically differs in number, the nature individuates itself. But if

it does not【intrinsically differ in number], then it follows that in themselves the humanity of Socrates and that of Plato would be the same ln number. And, just as a nature could be compared with another nature, so also could the added be compared with the added. But, for now, I leave this view.

10.

Argumenta in contrarium pauca sunt et parvi momcnli. I. Quicquid constítuit individuum materialiter, non constituit formaliter. Sed entítas individuum constítuit ipsum materialiter. E.Resp. negando maiorem, quia materiale et formale individui, seu species et individuum non differunt realiter. II. Si essentía in se caret existentía, nec eam implicat, sequitur , quod sit in se indifferens. Sed verum prius; quia quod sub opposito alicuius esse et concipi potest, id istud non includit. Sed sine existentía .essentía esse ac concipi potest. E. Resp.essentía vel sumitur, ut est in intellectu, et pro concepta quidditativo ; sic non est existentía de

ratione essentiae; vel prout est in re. Sic nego, esse posse sine existentia. III. Essentiae propria unitas, nimiram formalis, seu specifica, est minor unitate numerali. E. Ista non competit ei per se, quum ipsi ejus oppositum per se competat Resp. neg. antecedens de unitate extra intellectum. Sunt haec argumenta pleraque Soncinatis L 7. Met q. 31. Qui et objicit de accidentíbus, quae solo numero differentia non possint esse in eodem subjecto simul, quod tarnen falsum; item de partibus continui divulsis. Verum nos accidentia et entia incompleta removemus a nostra tractatione.

10.

The arguments opposing this view are few and of little moment.

I.Whatever is a material constituent element of the individual is not a formal constituent element. But entity of an individual is a material constituent element.Therefore,[the entity of an individual is not a formal constituent element of it] .I respond by denying the major in that material element and the formal element of the individual, or species and individual, do not differ really.

II. If essence in itself lacks existence, neither does it imply it. It follows

that essence is indifferent in itself [ to existence]. But the first is true

in that what can be and can be conceived as opposite to something else does not include that something else. But essence can be and can be conceived without existence. Therefore, [ essence does not include existence]. I respond : essence is either taken as it is in the intellect and for the quiditative concept and on this view existence is not in the idea of essence;or it is taken according as it is in the thing and on this view I deny that it can be without existence.

III.The proper unity of essence,namely,the formal or specific unity, is less than numerical unity. Therefore,numerical unity is not per se appropriate to formal unity,since the opposite of formal unity agrees per se with numerical unity. I respond by denying the antecedent concerning unity outside the intellect.

These are the many arguments of Socinas(1.7.Meta.q.31).He also

objects, concerning accidents that are different only in number, that they

could not be in the same subject at the same time,Which is nevertheless false.He likewise objects concerning the separated parts of the continuum.But we have left accidents and incomplete beings out of the scope of the present undertaking.

11.

Secunda opinio est, quae negationes ponit principium individuationis. An vero quemquam habuerit,

qui defendent, valde dubito, nisi fortasse aliquem Noininalium obscuriorem. Tanto magis autem suspectum est, quod Bassoli u s refert quosdam, quiprincipium individui dixissent existentiam cum duplici ne- gatione, quod satis improbabile, nec ullam convenien- tiam habet. 'Praeterea alii, qui meminere, non ad- junxere existentiam. Bassolius quoque ipse, ac si duae sententiae essent, separatím existentiam et negationes refutat. Vix tamen potuit esse ex toto Nomi- nalis, qui hoc defendit; nam illi praesupponunt, universale magis esse ens, quam singulare. Quicquid autem sit de autore sententiae, ita concipi potest, ut a summo genere per differentias determinatо ad subalterna, inde infimam speciem descendas, ibi vero ulterius nequeas, et negatio ulterioris descensus sit intrinsecum formale individui. Et esset haec de individuo sententia, quemadmodum Occami de puncto, qui in Logic. praedic. quant. et tr. de euсha- rietia dixit, referente Pererio 1. 10. c. 5, superficiem esse nihil aliud, quam corpus cum ne gatione exten sionis in profund itate ulterioris, line am in altitudine, punctum in longitudine. Porro prior negatio divi- sionis, est quasi generalis individui, altera vero negatio identitatis cum alio, faciet hoc Individuum ab alio vere distinctum.

11.

The second opinion is that which posits negations as the principle of individuation. But I doubt strongly whether it has anyone to defend it,

except, perhaps, some obscure nominalist.But so much the more is it suspect in that Bassolis refers to some who had said that the principle of individuation was existence with a double negation, which is improbable enough and does not have any consistency. Moreover some,Who have treated of it , do not mention existence. Too, Bassolis himself, as if there were two opinions, refutes existence and negations separately. Nevertheless, there could hardly on the whole be a nominalist who defended this, for such a thinker would have to suppose that the universal is more being than the singular. But whatever the case concernlng lts author, the position can be conceived in the following manner. From the summum genus through differences detemined by the subaltern, one should descend to the infima species.But there you can not【descend】further and

the negation of further descent would be the formal, intrinsic【principle】of the individual. And this opinion concerning the individual would be similar to Occam's about the point who(in Logic, praed, quant. and tr. de Eucharusta)says, according to Pererius(1:10,C.5), that surface is nothing other than body with negation of extension in further depth, the line in further breadth, and the point in further length.The first negation

that of division, is, as it were,the【principle】of a general individual. But the other negation, that of identity with another, would make this

individual truly distinct from another.

12.

De hac sententia Mercenar. Dilucid. de principio ind. Part. 1. c. 2. et fuse de Bassolis 1. 2. Sent. d. 12. q. 4 artic. I. Fundamentum eorum est, quod persuasi fuere, nullum positivum posse statui.

Sed non videre, quod natura possit individuare se ipsam. Oppugnari possunt facile: Individuum aut extra jnteliectum a negationibus constituitur, aut in intellectu.

Si hoc eorum responsio, nihil facit ad rem; si illud:

quomodo ens positivum constituí potest a negativo?

Praeterea negatio non potest producere accidentia individualia; deinde: omnis negatio est alicuius positivi,

itlioqtmt erit solum verbotenus negatio. Sint igitur duo individua Socrates et Plato: principium Socratis erit negatio Platonis, et principium Platonis negatio Socratis, erit igitur qeutrubi aliquid positivum, et in quo possis, pedem sistere. Acuta alia argumenta apud Bassolium vide.

12.

Concerning this position, See Mercenadus(Dilucid. de Prin. Ind., Par 1, c.2)and at length Bassolis(1:2, d. 12, q. 4, art. 1). The foundation of these is that they【those inclined to maintain the position】were persuaded that nothing positive could be established. But they did not see that nature could individuate itself. This【position】can be easily opposed the individual is constituted by negations,either outside the mind or in the mind. If the latter, their answer has nothing to do with the issue in question【since an intrinsic principle is sought】. If the former, how can positive being be constituted by negative being?Moreover negation cannot produce individual accidents. Then too, every negation is of something positive; otherwise, there would only be verbal negation. Therefore, let there be two individuals−Socrates and Plato. Then the principle of Socrates will be the negation of Plato and the principle of Plato will be the negation of Socrates. In either case there will be something positive on which you can stand. See other acute arguments in Bassolis.

13.

Tertia sententia est, existentiam esse principium individuationis. Hanc Pr. Murcia cuidam Carthusiano in 2. sent. d. 3., qui an sit Dionysius Rikelius (sane hunc in sententias scripsisse certum est), dicere non habeo; Fonseca Nicolao fioneto в.Met.c. 1. id defendenti tribuit, V. Met. c. 6. q. 2. §. 1.Dupliciter autem capi potest, partím ut existentía realis aliquis sit modus rem intrinsece individuans, ab ejus essentía a parte rei distmctus, quad si ita est,

defendí minime posest, ut mox patebit. Sin ab essentia solum ratione differret, nobiscum egregie coincidit et exprimit praeterea, quo respectu essentia sit principium individuationis. Atque ita intelligo Excell.

Scherzerum, Praeceptorem meum summo studio observandum. q. 42. Breviar. Metaph.

Eustachii de S. Paulo.

13.

The third position is that existence is the principle of individuation.

Murcia (in 2 sent., d. 3) attributes this to some Carthusian. I cannot say

whether this might be Diqnysius Yon Rickel - it is certainly the case that

he wrote on the sentences. Fonseca attributes it (in V Meta., c. 6, q. 2,

1) to Nicholas Bonetus.

But this [position] can be taken in two way's. In one way, existence might

be some real mode, intrinsically individuating the thing and distinct a

parte rei from its essence. If this is the case, it can by no means be

defended, as will become clear shortly. But, if [existence] differs only

I/mentally from essence, [this position] agrees uncommonly well with us.

Moreover, it expresses in what respect essence would be the principle

of individuation. And so I understand the excellent Schertzer, preceptor,

based on my careful reading of his q. 43, Breviarum Eustachii de S.

Paulo.

14.

Nobis igitur cum prioribus potissimum agendum est, quos refutat Scot. sent 2. d. 3. q. 3. et ejus

sectator Bass. ib. q. 4. art. 1. f. 179. Argumenter autem: I. si essentia et existentia sunt idem a parte rei,

sequitur, quod existentia sensu adversariorum non sit principium individuationis. Sed verum prius. E. et posterius. Minorem sic fundamentaliter probo : quaecumque realiter differant, possunt a se invicem separan.

Sed essentia et existentia non possunt separan. E.Quae ad majorem respondent Capreol. 1. d. 8. q.

1., et Cajetanus de ente et essentia, q. Ц. nullius sunt momenti. Minor probatur, partim quod essentia non possit auferri, partim existentia.

14.

Therefore, we shall deal especially with the first, whom Scotus (2 sent.,

d. 3, q. 3) and his follower, Bassolis, (Ibid., q. 4, art. 1, f. 179) refute.

Hence, I argue as follows. If essence and existence are the same a parte

rei, then it follows that existence - in the adversaries' sense - is not the

principle of individuation. But the first is true. Therefore, the second is

true. I prove the minor as follows. Whatever things really differ can, by

turns, be separated from each other. But essence and existence cannot

be separated. Therefore, etc. What Capreolus (I. d. 8, q. 1) and Cajetan

(de Ente et Essentia, q. ll) respond to the major is of no moment. The

minor is proved in that, on the one hand, essence, and, on the other hand,

existence could not be taken away [from each other].

15.

Illud probo: Oírme, quod aufertur, existit, praeciso eo, a quo aufertur; ablatio enim tamquam actio ad id, a quo aufertur, terminate. E. essentia existit,

praecisa existentia, quam implicat. Hoc, quod existen'

tia non possit auferri ab essentia, negant adversarii,

quorum longam seriein vide apud Petrum de Pomania Scotistam, 1. 1. sent. dis t. 36. q. unie. pag. 976.

Sed argumentor contra: esseatia, ablata existentia, aut

est ens reale aut nihil. Si nihil, . aut non fuit in

creaturis, quod absurdum, aut non distincta ab existentia fuit, quod.intendo. Sin ens reale fuit, aut pure postentiale, aut ens actu. Sine dubio illud; nam non

potest esse actu, nisi per existentiam, quam tamen separatam esse praesupponimus. Si igitur essentia est pure potentialis, omnes essentiae sunt nqateria prima.

Nam duo pure potentialia non differunt, ne relatione

ad actum quidem, quia haec relatio, quum ad ens in potentia sit, non est realis. Si igitur essentiae non differunt a materia, sequitur, quod sola materia

sit pars essentialis, et res non differant specie, v. g.

essentia bruti ab essentia hominis. Nam neutra

formant includit, quae est principium distinctionis specificae, et duo pure potentialia non differunt.

Et si dicas, differre per relationes ad Ideas: non est

relatio realis, esset enim accidens in DEO. De discrimine

essentiae et existentiae v. Posnaniensem 1. с.Soncin. 1. 4. Met. q. 12. et 1. 9. M. q. 3. Fonsec.

IV. Met. q. 4. Per. 1. 6. c. 14. Existentiam oppugnat Bassol. 1. c. Soncin. 7- Met. q. 32. Ramoned.in Thomam, de Ent. et. Essent. p. 399.

15.

I prove the first [that essence cannot be taken away from existence].

Everything which is taken away exists, once having been separated,

apart from that which is taken away; for a taking away, as an action,

terminates in that which is taken away. Therefore, essence exists apart

from existence, which is perplexing.

The opponents deny the second, that existence could not be taken away

from essence - a long list of them may-be found in Posnaniensis, the

Scotist (I sent., d. 36, q. 1, p. 976). But I argue against this. Essence,

once existence is taken away, is either a real thing or nothing. If nothing:

either it was not in creatures, which is absurd; or it was not distinct from

existence, which is what I maintain. If, on the other hand, [essence] is

a real being, it is either purely potential or actual being. Without doubt

[it must be] the former, for it cannot be actual except through existence

which, however, we have supposed to be separated. If, therefore, essence

is purely potential, all essences are prime matter. For two purely potential

things do not differ, not even by relation to act, because this relation,

since it would be to a being in potency, is not real. If, therefore, essences

are not different from matter, it follows that matter alone would be the

essential part and things do not differ by species, for example, the essence

of a brute and the essence of a man. For neither includes form, which

is the principle of specific distinction and two purely potential things do

not differ. And, if you say that they differ through relations to the Ideas,

there is no real relation, for then there would be an accident in God.

On the difference between essence and existence, see Posnaniensis (1oc.

cit.), Socinas (4 Met., q. 12 and 9 Met., q. 3), Fonseca (4 Met., q. 4),

and Pererius (I, 6, c. l4). Bassolis (loc. cit.), Socinas (7 Met., q. 32), and

Ramoneda (i-n Thomam de Ente et Essentia, p. 399) oppose existence.

16.

IV to et ultimo loco Scoti haecceitas offert se certamini, quam is attulit 2. sent. d. 3. q. 6. et teste Z ab are lia lib. de Constitutione individui, c. 8. Quodlibet. q. 2. art. 3. et Comment. in V. Met. t.12, ac discipuli pro juramento suo (ut meminit Mercenar. in respunsionc ad cujusdam Scotistae impugnationem suae sententiae) certatim defendenmt : in quibus satis vetustas est, et unde audacter ejus sensum rimeris, Joh. de Bassolis, ipsius Scoti auditor, Оccamo tamen fortasse prior, quia ejus contra Scotum placita nullibi refutat.

16.

In the fourth and last place Scotus'haecceity offers itself for battle. He presents his case in 2 sent.d .3, q.6 and, as Zabarella testifies【in his book】On the Constitution of Individual, chapter 8,in his Quodlibeta,q.2, art. 2, and also in his Commentary of Metaphysics V,t.12. And Scotus' disciples on account of their oath(as Mercenarius relates in response to the attack of some Scotist on his Sentences)defend him earnestly. Of these, there is a well−established one, from whom you will boldly find out his meaning, Johannes de Bassolis【Bassolius】,a student of Scotus himself,but possibly before Ockham,because Bassolis nowhere refutes

his [i.e.,Ockham's] views against Scotus.

17.

Notura autem est, Sc o tum fuisse Realium extremum, quia universalia veram extra mentem realitatem habere statftit, quum Thomas formale eorum proficisci ab intellectu vellet. Ne tamen in sententiam, vergeret tributam ab Aristotele Platoni, distinctionem formalem commentus est palliando errori, quae esset quidem ante operationem intellectus, diceret tarnen , respectum ad eum. Нас credidit genus distinguí a differentia, et consequenter differentiam numericatn a specie: quoniam enim universalia realia esse praesupposuerat, vel contradicendi studio, vel quod Thomae sententiam inexplicabilem putaret, Nominalium incredibilem : necesse fuit, singularia ex universali et, aliquo superaddito oriri; ut autem est proportio inter genus et speciem, ita inter speciem et individuum, quare ut illic differentia specifica est,ita hic individuificam esse concludebat.

17.

Now,it is known that Scotus was an extreme realist,because he held that universals have true reality outside the mind, while Thomas would prefer their formal character to originate in the mind. But, so that he would not adopt the view attributed by Aristotle to Plato, he contrived the“formal distinction”to hide his error.Indeed, this distinction is supposed to obtain before the operation of the intellect and yet he says that it holds with respect to the intellect.Under this rebric he believed genus to be distlnguished from difference, and consequently, numerical difference fromo species: for, because he supposed universals to be something real(either out of zeal for argument or that he thought that Thomas' opinion was inexplicable or that of the nominalists incredible),it was necessary that singulars originate from a universal with something added. But, just as there is a proportion between genus and species,so too【there is a proportion】between species and individual. Therefore,just as there is a specific diffrence in the first case,so too,be concluded,there is an individual difference in the second case.

18.

Hanc, eludendae Aristotelis autoritati, appellabat materiam totius. Nam, inquiebat, est forma totius, v.g.humanitas, tanquam abstractum hominis, cui opponitur materia totius, nempe haecceitas, et forma partis, ánima rationalis, cui corpus, ut materia partis, opponitur. Sed id nihil eçt; natn haecceitas, si est materia totius, debet cum humanitate concretum constituere hominem. At ilia constituit hunc hominem, deberet igitur alia vera materia totius dari,quae hominem in universo constitueret. Taceo quod illa haecceitas esset potius forma, contrahit enim et distinguit; praeterea, si, ut yolunt plerique vetustiorum, v. Per e r. 1. 6. c. 6., quidditas rei secundam Aristotelem sola forma continetur, ut materia sit solum vehiculunt, forma totius et partis apud Aristotelem sunt idem; v. Mercen 1. c. c. 5. et per Apo- logiam totam, ac Za b. 1. c. c. 8 et 10.

18.

Making sport of the authonty of Aristotle,he called this individual difference "matter of the whole." For, he would say,there is a form of the whole, e.g. , humanity as abstracted from man,to which is opposed the matter of the whole,namely,haeccelty. And there is a form of the part, i. e. , rational soul, to which body, as matter of the part, is opposed. But this is nothing, for haecceity, if it is the matter of the whole, ought to constitute with humanity something concrete, man. But this[composite ]constitutes this man. Thus, some other true matter of the whole ought to be provided, which would constitute man in the universal.I do not mention that this haecceity would be more【like】form,for it contracts and distinguishes. Besides, if, as many of the more well-established【Scotists】would have it ーSee Peredus 1.6, c. 6・6ーthe quiddity of a thing according to Aristotle consists of the form alone, Such that matter would be only a vessel, then form of the whole and form of the part−according to Aristotle−are the same. See Mercenadus 1. c. , c. 5 and throughout Apology,as well as Zabarella, 1,c., c 8 and 10.

19.

Existentiam Scotus non admisit, quamvis eam formaliter distinguat ab essentia; nam apud eum species, praecisa haecceitate, existit. Defendit S cо tum ex recentioribus Petrus Föns e c a, quamvis a Murcia pro nostra sententia citetur, v. Met. c. 6. q. 5 et Eustachius a St. Paulo 1. c. Vice versa, quod mireris, sunt qui Suaresiunt ad Scotum trahant, quod asserat, D is p. Met. 5., sect. Ц. N. 16, indi- viduum addere aliquid supra communem naturam, ra-, tione distinctum. At ultima verba nubem hanc facile disjiciunt. Plerique enim concedunt, quod per opera- tionem mentis detur differentia individualis : an igitur -Fr. Oviedo et similes propterea Scotistae erunt? Primum autem Scoti fundamenta ponam et solvam, inde adductis machinis oppugnabo.

19.

Scotus did not admit existence, although he distinguishes it formally

from essence, for according to him species exists apart from haecceity.

More recently, Petrus Fonseca dtfends Scotus, although Murcia is cited

forouropinion. (See V Met. c. 6 q. 5 and Eustachius a S. Paulo 1.c.) Onthe

other hand, which might cause one to wonder, there are those who reduce

Suarez to Scotus, because of what he [Suarez] says in Disputationes Metaphysicae 5, s. II, n. 16. There he says that the individual adds something beyond common nature, which something is distinguished in reason. But these last words easily dispel the cloud. For many conclude that individual difference is provided by an operation of the mind. Are,

therefore, Fr. Oviedo and others of like persuasion, as a result, Scotists?

But I will Brst set out the basic principles of Scotus' view and refute

them. Then, I will attack them in more detailed arguments.

20.

Primum pro Scoto argumentum ab ipso allatum, re- censente Pererio 1. 6. c. 10., est: omnis unitas aliquam éntitatem sequitur. E. et numerica; illa autem entitas non est id, quod in specie includitur. E. aliquid ei superaddi tum, nempe differentia individualis. "Resp. unitas entitatem sequitur in conceptu, in re idem est. Neo entitas numerica differt a spedfica realiter. II. Species non per formam vel materiem vel accidentia etc. contrahitur. E. relinquitur haecceitas. Resp. per nihil contrahitur, quia extra mentem nulla est. III. Quae differunt, per aliqua primo diversa differunt. E. Socrates et Plato per ultimum differunt, nempe haecceitatem.

Resp. Qua6 differunt, limito: nisi sint ipsa primo diversa,et se ipsis differant, per aliqua etc. Sic nego Minorem.

20.

The first argument on Scotus' behalf, which he himself proposed, and

as it is given in Pererius (1. 6, c; lO), is as follows. Every unity follows

upon some entity. Therefore, numerical [unity follows upon numerical

entity]. But that entity is not that which is included in species. Therefore,

there is something super-added to species, namely individual difference.

I reply that unity follows entity in concept., it is the same in the thing.

Neither does numerical entity differ really from specific [entity].

II. Species is not contacted either through form or through matter, or

through accidents, etc. Therefore , there remains haecceity . I answer that it is contracted through nothing, because there is no [spacies] outside the mind.

III. Those things that differ do so through something already diverse.

Thus Socrates and Plato [differ] through some ultimate difference, namely

haecceity. I answer: "Those thing that differ... " must be qualified,

bylbdding: "unless they are themselves already diverse and differ from

themselves through something [already diverse]," etc. Hence, I deny the

minor.

21.

IV. Species per differentiam specificam contrahit genus.E. individuum per differentiam numericam speciem.

Resp. nego antecedens extra mentem. v. Fonseca 1. c.

Individua sub aliqua natura univoca sunt. E. quaedam

primo diversa includunt. Resp. ut prius. VI. item: per differentiam

individuum spëciem excedit. E. est talis differentia.

Re.sp. ut prius. VII. Bassolus: natura specifica

habet ex se unitatem minorera numerali, et aliant ab ea

realiter. E. Resp. Nego antecedens. De probatione infra.

Argumento HI. praecipue torsit Suessanus, Dilucid. 1. 5., Zimaram et Mercenarium, apud quem

vide 1. c. c. 5. Nullus tamen in hanc mentem respondit, quia aliis fundamentis nitebantur.

21.

IV. Species contracts genus through specific difference. Therefore, the

individual [contracts] species through numerical difference. I answer by

denying the antecedent as true outside the mind.

V. From Fonseca (1.c.): Individuals under some nature are univocal.

Therefore, they include something already diverse. I answer las before.

vI. Similarly: The individual exceeds the species through difference.

Therefore, there is such a difference. I respond as before.

VII. From Bassolis: Specific nature of itself has less than numerical

unity, and really has a unity other than numerical unity. Therefore, [there

is a nume,ical unity]. I respond by denying the antecedent. The proof

will be given later.

The third argument especially troubled Suessanus (Dilucidation, book

v), zimara, and Mercenarius (see 1.c., chapter 5). But no one has

answered this view, because they depended on other foundations.

22.

Argumenter contra Scotum. I. Si genus et differentia tantum ratione distinguuntur, non datur differentia individualis. Sed verum prius: E. Major patet; nam etiam species et differentia numerica solum ratiöne distinguetur. Minor probatur : 1. Quae ante operationen! mentis differunt, separabilia bilia sunt. Sed genus et differentiae non possunt

separari. Quamvis enim sint loca quaedam Scoti,

quibus asserat, posse fortasse Deum facere, ut universalia sint extra singularia, et similiter genus extra specient, tamen id absurdum probo, quia nulla daretur divisio

adaequata: daretur animal nee rationale, nec irrationale.

Et daretur motio neque recta, neque obliqua. 2. Differentiae superiores praedicantur de inferioribus. v. g. haec rationalitas est rationalitas. E. differentia specifica includit in se differentiam generis. E. a genere non differt. Nam genus ad differentiam suam additam habet differentiam generis sui, quae et ipsa includitur a sua. Et ita ad usque summum. Et quia aliquando sistendum est, dixit Aristoteles: Ens praedicari de differentiis. Vide quaedam apud Soncin. I. 7 q. 36 et 37.

22.

I argue against Scotus.

I. lf genus and difference are distinguished only mentally, there is no

individuamifference. But the first is true. Therefore, etc. The major is

plain, for species and numerical difference will also be distinguished

only mentally. The minor is proved [in the following two arguments].

1. Those things that differ before the operation of the mind are separable. But genus and differences cannot be separated. For, although there

might be some place in Scotus in which he asserts that God, perhaps,

can bring it about that universals might exist outside of singulars and

likewise genus [exist] outside of species, nevertheless I prove this to

be absurd, because, if there is no adequate division [of genus], the,e

would be an anlmal neither rational nor irrational. And there would be

motion neither straight nor oblique. 2. Superior differences are predicated of inferiors, e.g., "this rationality is rationality." Therefore, specific

difference includes in itself the difference of genus. Therefore, it does

not differ from genus. For, genus with its own added difference has the

difference of its genus [e.g., animal has the dilrerence, animate, from the

superior genus, animate substance], which difference is included in it

[ just as the species, say, man, includes the difference of its genus, rational]. And so continuously to the summum genus. And, because there

must somewhere be a stop, Aristotle said that being is predicated of

differences. See what Socinas says (in 1. 7, q. 36 and 37).

23.

II. Si non sunt universalia ante nrentis operationem, non datur compositio ante mentis operationen!, ex universal! et individuante. Non est enim realis compositio,cujus non omnia membra sint realia. Sed verum. prius, E. Minor probatur: omne quod ante mentis operationem realiter ab altero ita differt, ut neutrum sit pars alterius vel ex toto, vel ex parte, potest ab altero separari. Nam in adaequate differentibus neutrum altero ad suum esse indiget. E. potest separari per potentiam Dei absolutem, \et solum pars a toto ita, ut id permaneat, est simpliciter inseparabilis. Minor prosyllogismus probatur : daretur enim linea realiter neque recta, neque curva, quod absurdissimum.

v. Ruv. log. de univers. q. 4.

23.

II. If there are no universals before the operation of the mind, there is no

composition from the universal and the individuating [cause or principle]

before the operation of the mind. For there is no real composition, not

all of whose members are real. But the first is true. Therefore, etc. The

minor is proved as follows. Everything that before the ope,ration of the

mind really differs from another, such that neither is part of the other

either wholly or partly, can be separated from the other. For in those

things adequately different neither stands in need of the other for its

own esse. Therefore, it can be separated through the absolute power of

God and only a part is separable simpliciter from the whole such that

it remains. The minor of the pro-syllogism is proved, for there would

really be a line neither straight nor curved, which is absurd. See Ruvius

(Logic. de Univ., q. 4).

24.

III. Si non datur distinctio formalis, ruit haecceitas. Sed veruni prius. E. Antequam probemus, de hac distinctione aliqua disserenda sunt. Videri autem possunt Stahl. Сотр. Metaph. c. 23.Soncin. 1. 7. -q. 35. Posnaniensis 1. sent. d. 34.dubio 64. Tribuitur communiter Scoto, ut media inter realem et rationis, unde ejus sectatores.dicti Formalistae. Наc putat distingo! attributa in Divinis, et relationes personales ab essentia, quidditates rerum inter se et a Deo, in esse cognito, praedicata superiora ab inferioribus , genus a difl'erentia, essentiam ab existentia: explicat earn Rhada, quod sit inter duas realitates seu formalitates, ih subjecto identificatas, diversas vero in ordine ad intellectum; differre a rationis distinctione, quod haec requirat ante

se operationem mentis in actu. Sed mire perplexi sunt et inconstantes, ubi haec in actu exercito applicanda sunt. Nam si haecceitas a specie solum differr,

quod apta est distincte movere intellectum, quam male ad principium individui affertur, quod praeciso intellectu quaeri debet? Quare necesse est, majus quiddam sub eorum verbis latere; Sed id absurdum est, quodcumque sit, simulatque enim, praeciso intellectu, differunt, non sunt sibi identificata.

24.

III. If there is no formal distinction, haecceity falls. But the first is

true. Therefore, etc. Before we provide the proof, some things must be

discussed concerning this distinction. Moreover, Stahlius (Comp. Met.

c. 23), Socinas (1. 7, q. 35), and Posnamiensis (1 sent., d. 34, dubio 64)

can be seen.

This distinction is commonly attributed to Scotus as a middle between

the real [distinction] and [that] of reason, whence his adherents are

called "Formalists." By this he takes to be distinguished the attributes of

God and the personal relations from his essence; the quiddities of things

among themselves, as these are known, from God; superior predicamenta

from inferior predicamenta; genus from difference; and essence from

existence. Rhada explains this [distinction] as that which obtains between

two realities or formalities identical in a subject but diverse in their order

to the intellect and differs from a distinction of reason in that such a

distinction requires before itself the actual operation of the mind. But

[Scotists] are exceedingly ambiguous and inconsistent as to when these

distinctions are to be applied in actual practice. For, if haecceity differs

from species only in that it is apt to move the intellect distinctly, how

poorly is it brought forward as the principle of individuation, which [principle] ought to be sought apart from the intellect? Whence, it must

be the case that something more is hidden under their words. But, it is

absurd, whatever it might be, for as soon as they [the alleged formalities]

differ outside the intellect, they are not identiated with each other.

25.

Posnaniensis illas formalitates interpretatuv:

çonceptus objectivos, et rationes intèlligibiles, seu

rem cum relatione ad conceptus in mente formales.

Sed id nihil est, nam cönceptus potins formalis fundetur in objectivо , si igitur etiam objectivus in formali daretur circulas, аc dum utrumque, fundaretur neutrum, et eyaneseret utrumque. Deinde ratio ilia intelligibilatitis esset vel ad conceptum divinum sive Ideas, sed hic illa relatío non esset realis; non enim cadit in DEUM accidens. E. Nihil superesset

distinctíoni a parte reí; vel ad verbum mentis, ut тоcant creatum. Sed si otnnis intellectus creatus tolleretur, ilia relatio periret, et tamen re,s individuarentur, E. tunc se ipsis. Addo, quod relatio ilia, si esset realis, haberet suam haecceitatem, esset enim singularis, et ita in infinitum. Praeterea est ad ens in potentia seu conceptum formalem, qui esse potest, et

si dicas, illam relationem formaliter differre a termino,quaero similiter de relatione lut jus relationis in infinitum. Nam et ipsa relatione ad intellectum indigeret.

25.

Posnaniensis understands these formalities as objective concepts and

intelligible notes, or as a thing with a relation to formal concepts in the

mind. But this is nothing, for the formal concept is founded properly

in the objective concept. If, therefore, the objective concept [is also

founded] in the formal, there will be a circle and, while each [does

the founding], neither is founded and each would vanish. Hence, that

relation of intelligibility would be either to the concept in God, namely

Ideas tin God's intellect]. But then that relation would not be real, for an

accident does not occur in God. Therefbre, nothing could still exist for

the distinction a parte rei [i.e., the distinction would lack a real founda-

tion]. Or that relation would be to the word of the mind, or a creature

of mind, as some say. But, if every created intellect is taken away, than

that relation would perish. Nevertheless, things would be individuated.

Therefore, [they would be individuated] by themselves. Add that this

relation, if it were real, would have its own haecceity - for it would be singular - and so on to infinity. Moreover, the relation is to a being in potency, or the formal concept, which can exist. And, if you say that this relation differs formally from its term, I ask in the above manner,

conceming the relation of this relation and so on to infinity. For this

relation itself requires a relation to the intellect.

26.

IV. Inexplicabile est, quo modo accidentia individuah'a ab haecceitate oriantur; ex nostra autem facile explicari potest, quia dantur dispositiones materiae ad formam, nullae veré speciei ad haecceitatem. Vid.Hervaeum, quodlib. 3. q.9.contra Scotum, apud Perer. 1. c., et Scaliger Exerc. 307 ad Cardan.

N. 17. Atque ita, Divina ope adjuti, sentenüas generales absolvimos.

26.

IV. It is inexplicable how individual accidents originate from

haecceity, for on our own view this can easily be explained, because there are

dispositions of matter to form, but no [disposition] of species to haecceity. See Hervaeus (Quod, 3, q. 9, contra Scotus) in Perenus,(1.c.) and Scaliger (Exer. 307 ad Cardan., n. 17).

COROLLARIA.

I. Materia habet de se actum entitativuna.

II. Non omnino improbabile est, materiam et quantitatem esse realiter idem.

III. Essentiaë rerum sunt sicut numeri.

IV. Essentiaë rerum non sunt aeternae, nisi ut sunt in Deo.

V. Possibilis est penetratio dimensionum.

VI. Hominis solum una est anima, quae vegetativam et sensitivam virtualiter includat.

VII. Epístolas tyranno Phalaridi adscriptas supposititias crediderim. Nam Siculi Dores e rant, hic

genus dicendi Atticum. Adde quod Atticismus

illo tempore durior, ut Thucydidis, sed hae sapiunt aetatem Luciani. Certe ubi combustionem

Perilli dependit *), declamatorem se prodit autor.

---------------

*)Legendum fortasse: depingit.

COROLLARIES

I. A matter of course, act entities [that is to say an existing reality].

II. It is not at all implausible that matter and quantity are actually the same thing.

III. The essences of things are like numbers.

IV. The essences of things are not eternal, or as in God.

V. It is possible that the dimensions can be penetrated.

VI. The soul of man is that it has virtually vegetative soul and sensitive soul.

VII. I [will] believe that the letters attributed of the tyrant Phalaris are interpolated.

Because the Siciliens were home of dorienne, while those letters were composed by Attic dialect. This dialect at the time of Phalaris, was also tougher, as [the show's writings] Thucydides, while these letters feel like the time Lucien. The author describes or the burning of Perillus, it betrays a coup on as a declamation.

注:

COROLLARIA以下、特にVIIについてはいくつかの議論がある(調査中)。

Phalarisについては以下のサイト(英語)及び書籍参照。

http://www.nndb.com/people/837/000097546/http://books.google.co.jp/books?id=lxtSYBtShVsC&output=html(p.84)

http://books.google.co.jp/books?id=2vTmU6MtxcQC(p.158)

追記:

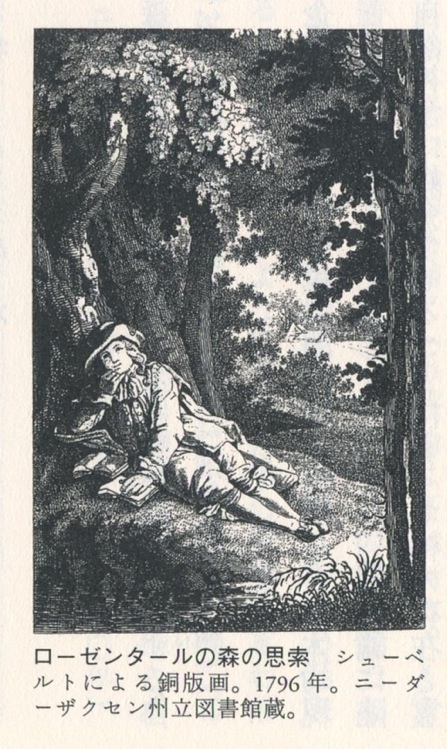

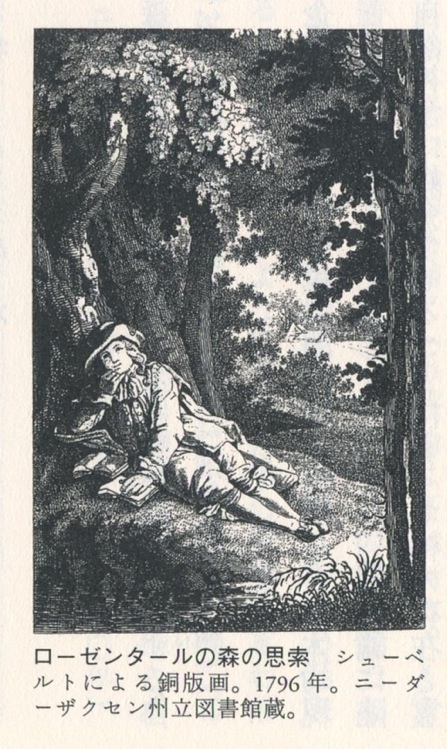

バッハが生まれる20年ほど前、ライプニッツ(1646-1716)はライプツィヒ、ローゼンタールの森で思索したという。

「私は自分が15才で、ライプツィヒのローゼンタールの森を独りで散歩していた時のことを思い出す。その時私は(スコラ哲学者たちの)実体的形相を固守し続けるべきかどうか思索していたのである。その結果、機械論が勝利を収め、私は数学研究に向かうことになった。」ニコラ=フランソワ・レモン宛書簡より

http://blog.livedoor.jp/yojisekimoto/archives/cat_50026615.html

http://homepage3.nifty.com/hiraosemi/li.htm

参考:岩波文庫『形而上学叙説』p10-11、シュプリンガー『ライプニッツ』p189 、『ライプニッツの普遍計画』p35

参考画像:

↓『哲学の歴史5』(中公新社、p523)より

Johann David Schubert ,1795

資料:

"Leibniz behauptet, daß nicht zwey

Blätter einander völlig ähnlich seyn."

Stich nach Schubert, 1796

http://www.lehrer.uni-karlsruhe.de/~za146/barock/leibniz1.htm

「識別できない二つの個物はありません。 私の友人に才気煥発な一人の貴族がいて、ヘレンハウゼン(Herrenhausen)の庭の中、選帝侯婦人の御前で私と話をしていたときのことでありますが、そのとき彼は全く同じ二つの葉を見つけられると思っていました。 選帝侯婦人はそんなことは出来ないとおっしゃいました。 そこで彼は長い間駆けずり回って探したのですが無駄でした。 顕微鏡で見られれば二つの水滴とか乳滴も識別され得るでしょう。」

(1716年6月2日クラーク宛第4書簡)

「互いに完全に似ている二つの卵、完全に似ている二つの葉とか草は庭の中には見いだされない。従って、完全な類似性は非充足的な抽象的な概念においてしか生じないが、その場合事物は、あらゆる仕方においてではなく、ある一定の考察様式に従って考察されているのである。」

「第一真理」(生前未発表)

http://nam-students.blogspot.com/2009/01/primae-veritaes.html#%E5%A4%A9%E4%BD%BF

【不可識別者同一の原理 principium identitatis indiscerniblium,principle of the identity of indiscernibles 】

(『モナドロジー』9など)

[自然においては、2つの存在がたがいにまったく同一で、そこに内的規定に基づく違いが発見できないなどということはなく、それゆえ、たがいに識別できない2つのものは、実は、同一の1つののものである]とされる。

http://www.edp.eng.tamagawa.ac.jp/~sumioka/history/philosophy/kinsei/kinsei02g.html

http://blog.livedoor.jp/yojisekimoto/archives/cat_50026615.html

Leibniz mit Herzogin Sophie, Karl August von Alvensleben und zwei Hofdamen im Herrenhäuser Garten. Illustration aus einer 1795 erschienenen Leibniz-Biographie von Johann August Eberhard

# Leibniz-Biographien. (Enth.: Gottfried Wilhelm Freyherr von Leibnitz / Johann August Eberhard. - Lebensbeschreibung des Freyherrn von Leibnitz / Johann Georg von Eckhart). Hildesheim ; Zürich ; New York: Olms 1982. ISBN 3-487-07239-4

http://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Datei:Leibniz_und_Alvensleben.jpg&filetimestamp=20070325202518

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_August_I._von_Alvensleben

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Leibniz_und_Alvensleben.jpg

仏版『社会問題の解決』より、人民銀行流通券↓(『人間の経済』78号森野栄一「プルードンの夢」*に詳しい。

http://www.grsj.org/book/booklibrary/ningennokeizai_78.pdf )

仏版『社会問題の解決』より、人民銀行流通券↓(『人間の経済』78号森野栄一「プルードンの夢」*に詳しい。

http://www.grsj.org/book/booklibrary/ningennokeizai_78.pdf )

*以下、参考までに、『人間の経済』第78号p26より、流通券の記載事項の翻訳。

「人民銀行の「流通券」見本には、券面にこうあります。

5フランシリーズ 人民銀行 No.***

5フラン流通券

加入者各位

一覧後、支払指図に対して、人民銀行が受領した総額5フランの、

諸君の産業の商品や生産物、用益で持参人に支払う

署名 P.J.PROUDHON et Co.

経理人 ****(署名)

<上記の他に、左右に、人民銀行という協会の約款、18条、20条が記載されています>

18条(左端に記載)

通常の正貨で支払われる銀行手形と異なり人民銀行券は永遠の社会的性格をもつ引渡指図であり、あらゆる組合員ないし全加入者によって、その事業や職業の生産物あるいは用益によって支払われる。

20条(右端に記載)

流通券は協会の全加入者にあらゆる支払いで受領される。協会は正貨での払い戻しを行わない。協会ヘ任意のものでしかないが、加入者のところでの受領の義務を保証する。加入者の名称、職業、住所地の一覧は協会の事業所に掲示されるであろう。」

注:

上記銀行券は、担保のある人民銀行のもので、交換銀行のものとは違うが、その計画の原案として交換銀行があり、定款の検討としてはこちらでも十分参考になるので以下を引用する。

/////////////////////////////////////

交換銀行設立計画

国有交換銀行

基本定款

下記署名者の、卸売商人、職人、企業家、産業家、所有者、経済学者、法律家、教師、著述家、芸術家、あらゆる種類の、またすべての身分、職業の生産者たちの間で、下記事項の合意、決定をみた。

第一編

《一般条項》

第一条 署名者および本約款に同意するもの全員が、国有交換銀行の名称のもとに商業組合を構成する。

第二条 組合員の目的は下記の通り。

一、交換銀行を設立することで、組合の各成員に、貨幣の助けなしに、特にまた即刻に、あらゆる生産物や食料品、商品、サービス、労働を獲得させ、

二、その後、生産者の条件を変更して、農業および産業労働の再組織化をもたらす。

第三条 組合は万人のものである。

全市民は、例外なく、これに属するよう要請される。組合員であるためには、いかなる出資も必要ではなく、本定款に同意し、交換銀行の信用紙券でのあらゆる支払を受け入れるだけで十分である。

第四条 組合は資本を有しない。

第五条 その有効期間は無制限である。

第六条 その所在地はパリに置く。

*以下、参考までに、『人間の経済』第78号p26より、流通券の記載事項の翻訳。

「人民銀行の「流通券」見本には、券面にこうあります。

5フランシリーズ 人民銀行 No.***

5フラン流通券

加入者各位

一覧後、支払指図に対して、人民銀行が受領した総額5フランの、

諸君の産業の商品や生産物、用益で持参人に支払う

署名 P.J.PROUDHON et Co.

経理人 ****(署名)

<上記の他に、左右に、人民銀行という協会の約款、18条、20条が記載されています>

18条(左端に記載)

通常の正貨で支払われる銀行手形と異なり人民銀行券は永遠の社会的性格をもつ引渡指図であり、あらゆる組合員ないし全加入者によって、その事業や職業の生産物あるいは用益によって支払われる。

20条(右端に記載)

流通券は協会の全加入者にあらゆる支払いで受領される。協会は正貨での払い戻しを行わない。協会ヘ任意のものでしかないが、加入者のところでの受領の義務を保証する。加入者の名称、職業、住所地の一覧は協会の事業所に掲示されるであろう。」

注:

上記銀行券は、担保のある人民銀行のもので、交換銀行のものとは違うが、その計画の原案として交換銀行があり、定款の検討としてはこちらでも十分参考になるので以下を引用する。

/////////////////////////////////////

交換銀行設立計画

国有交換銀行

基本定款

下記署名者の、卸売商人、職人、企業家、産業家、所有者、経済学者、法律家、教師、著述家、芸術家、あらゆる種類の、またすべての身分、職業の生産者たちの間で、下記事項の合意、決定をみた。

第一編

《一般条項》

第一条 署名者および本約款に同意するもの全員が、国有交換銀行の名称のもとに商業組合を構成する。

第二条 組合員の目的は下記の通り。

一、交換銀行を設立することで、組合の各成員に、貨幣の助けなしに、特にまた即刻に、あらゆる生産物や食料品、商品、サービス、労働を獲得させ、

二、その後、生産者の条件を変更して、農業および産業労働の再組織化をもたらす。

第三条 組合は万人のものである。

全市民は、例外なく、これに属するよう要請される。組合員であるためには、いかなる出資も必要ではなく、本定款に同意し、交換銀行の信用紙券でのあらゆる支払を受け入れるだけで十分である。

第四条 組合は資本を有しない。

第五条 その有効期間は無制限である。

第六条 その所在地はパリに置く。