簡易目次

この本は、大学レベルのマクロ経済学における構造化された2学期(おそらくそれ以上)のシーケンスを提供します。

物語はすべての背景の学生にアクセス可能であり、すべての数学的および高度な教材は必要に応じて避けることができます。

パートA:はじめに

1はじめに

2マクロ経済学の考え方とやり方

3経済史と資本主義の台頭の概要

4国民所得と製品会計のシステム

5労働市場の概念と測定

6部門別会計と資金の流れ

7方法、ツールおよびテクニック

8マクロ経済学におけるフレーミングと言語

パートB:通貨、通貨、および銀行取引

9主権通貨論:政府とそのお金

10お金と銀行

パートC:国民所得、出力および雇用の決定

11古典的システム

12ケインズ氏と「古典」

13実効需要の理論

14労働に対するマクロ経済的需要

15総支出モデル

16総計の供給

パートDの雇用とインフレーション:理論と政策

17失業率とインフレ

18フィリップス曲線とその先

19完全雇用ポリシー

開かれた経済学における第E部経済政策

20金融政策および財政政策の概要

21主権国における財政政策

22財政空間と財政の持続可能性

23主権国における金融政策

24開放経済における政策:為替レート、国際収支および競争力

パートF

経済的不安定性

25利益創出における投資の役割

26不安定経済の安定化

マクロ経済思想の第G部歴史

27経済思想史の概観

IS-LMフレームワーク。

29現代経済学派

30マクロ経済学における新たな金銭的合意

パートH

現在のデート

31最近のポリシーディベート

32世界金融危機を踏まえたマクロ経済学

33将来のためのマクロ経済学

ラーナー『雇用の経済学』162頁

基本的な諸関係は第十五図に要約される。Mは貨幣を、iは利子率を、Iは投資を、Cは消費を、Yは所得

を、Eは雇用を、i(M, Y)は流動性選好(数々の所得水準において与えられる貨幣額を、公衆に保有させよう

とするに必要な利子率で測定される現金保有の意思)を、I(i)は投資機会(投資決意が利子率に依存するところの方法)

図の最上部には、所得水準に依存する(あるいは、所得水準によって決定される)雇用量がある。所得水準は

消費性向と投資とに依存する。投資は投資機会と利子率とに依存する。最後に、利子率は流動性選好と貨幣額と

に依存する。

地面に接する四つの煉瓦の部分があるこの家で、唯一つのものが単一の文字で表わされていることが、注意さ

れるべきである。その一つのものとは、ここでは、外部から幣当局によって決定されると考えられる貨幣額M

である。地面に接する他の三つの支柱~i(M, Y) I(i)およびC(Y)~は、何か外部当局によって与えられる

独立した額ではなくて、その構築物内のその他の要素の間の関数あるいは諸関係を表わしている。そして、その

すべてはお互いに密接に依存しあうのである。

______

| |

| 政策 |[E]20~24

|______|

___|________

/ \

/ \

/ E非雇用 \[D]17~19

/ /雇用 \

/____________________\

| Y所得 |[C]11~16

|____________________|

| | | I投資 |

|C(Y) |______________|

|消費 | |I(i) | i利子率 |

|性向 | |投資 | |_______|

| | |機会 | |i | |M |

|___| |___| (M,Y) |貨幣|

([A]) [F] 流動性選好 [B] 25~26 / 9~10

/

歴史[A]1~8,[G]27~30,[H]31~33現状,未来

#4:59 CPI:消費者物価指数、#5:69雇用非雇用分類、#12:190流動性選好、#17:262交換方程式、#19:31 JG:雇用保証、#25:403 複利、#28:445,454 IS-LM

《図の最上部には、所得水準Yに依存する(あるいは、所得水準Yによって決定される)雇用量Eがある。

所得水準Yは消費性向C(Y)と投資Iとに依存する。

投資Iは投資機会I(i)と利子率iとに依存する。

最後に、利子率iは流動性選好i(M,Y)と貨幣額Mとに依存する。》ラーナー

パートC:国民所得、出力および雇用の決定#11〜16 パートD:非雇用とインフレーション:理論と方針#17〜19

PART A: INTRODUCTION & MEASUREMENT #1~8

PART B: CURRENCY, MONEY & BANKING #9~10

PART C: NATIONAL INCOME, OUTPUT AND EMPLOYMENT DETERMINATION #11~16

PART D: UNEMPLOYMENT AND INFLATION: THEORY AND POLICY #17~19

PART E: ECONOMIC POLICY IN AN OPEN ECONOMY #20~24

PART F: ECONOMIC INSTABILITY #26~26

PART G: HISTORY OF MACROECONOMIC THOUGHT #27~30

PART H: CONTEMPORARY DEBATES #31~33

___

以下詳細目次:

CONTENTS

List of Figures xvii

List of Tables xix

List of Boxes xx

About the Authors xxi

About the Book xxii

Tour of the book xxiv

Preface xxvi

Acknowledgements xxviii

Website Materials xxix

^

内容

図のリストxvii

テーブル一覧xix

ボックス一覧xx

著者についてxxi

本についてxxii

本のツアーxxiv

はじめにxxvi

謝辞xxviii

ウェブサイト資料xxix

PART A: INTRODUCTION AND MEASUREMENT 1 [#1~8]

(1 Introduction/2 How to Think and Do Macroeconomics/3 A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism/4 The System of National Income and Product Accounts/5 Labour Market Concepts and Measurement/6 Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds/7 Methods, Tools and Techniques/8 Framing and Language in Macroeconomics)

^

パートA:導入と測定1 [#1〜8]

(1序論/ 2マクロ経済学の考え方と行動/ 3経済史と資本主義の台頭の概要/ 4国民所得と製品勘定の体系/ 5労働市場の概念と測定/ 6部門別会計とその流れ資金/ 7方法、ツール、テクニック/ 8マクロ経済におけるフレーミングと言語)

about the book

Macroeconomics has eight parts.

In Part A Introduction and Measurement, we introduce students to the subject matter of macroeconomics, and how it diff ers from microeconomics (Chapter 1). We note that it is a highly con-tested discipline, and that macroeconomic reasoning can be blighted by the fallacy of composition. Th e impor-tance of developing skills of critical thinking is emphasised (Chapter 2). In Chapter 3, we place capitalism in context by a brief overview of economic history in which its rise to prominence is explored. Every discipline has its own language in the form of concepts and theories that provide the basis for understanding, and not merely describing, the relevant phenomena. To this end, we develop some initial conceptual understanding of national accounts, the labour market and sectoral balances (Chapters 4–6). Concepts and theories can also be depicted and understood through the development of formal mathematical models. Some introductory mathematical material is provided in Chapter 7. Students need to recognise the importance of framing and language in learning macroeconomics (Chapter 8).

パートA「導入と測定」では、マクロ経済学の主題、およびミクロ経済学との違いについて学生に紹介します(第1章)。これは非常に矛盾した分野であり、マクロ経済的推論は構成の誤りによって軽視される可能性があることに注意してください。批判的思考のスキルを伸ばすことの重要性が強調されています(第2章)。第3章では、著名主義へのその上昇が探求されている経済史の簡単な概観によって資本主義を文脈に置いている。すべての分野には、関連する現象を説明するだけではなく、理解の基礎を提供する概念と理論の形で独自の言語があります。そのために、国民経済計算、労働市場、部門別収支についての最初の概念的理解を深めます(第4章〜第6章)。概念と理論は、形式的数学モデルの開発を通して描写され理解されることもできます。第7章では、いくつかの入門用数学教材が提供されています。生徒は、マクロ経済学の学習におけるフレーミングと言語の重要性を認識する必要があります。

1 Introduction 2

1.1 What is Economics? Two Views 2

Orthodox, neoclassical approach 3

Heterodox approach – Keynesian/Institutionalist/Marxist 5

What do economists do? 8

Implications for research and policy 8

1.2 Economics and the Public Purpose 9

1.3 What is Macroeconomics? 12

The macro model 12

The MMT approach to macroeconomics 13

Fiscal and monetary policy 15

Policy implications of MMT for sovereign nations 16

Conclusion 17

References 17

^

1 はじめに2

1.1経済学とは2つの眺め2

正統派、新古典派のアプローチ3

ヘテロドックスアプローチ - ケインジアン/制度主義者/マルクス主義者5

経済学者は何をしますか? 8

研究および政策への影響8

1.2経済学と公的目的9

1.3マクロ経済学とは12年

マクロモデル12

マクロ経済学へのMMTアプローチ13

財政金融政策15

主権国に対するMMTの政策的意義16

まとめ17

参考文献17

#1 Functional finance and modern monetary theory – Bill Mitchell – 2009/11/1

#1:9,17

世界人権宣言

Now, Therefore THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY proclaims THIS UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

世界人権宣言(せかいじんけんせんげん、Universal Declaration of Human Rights、略称:UDHR)は、1948年12月10日の第3回国際連合総会で採択された、すべての人民とすべての国が達成すべき基本的人権についての宣言である(国際連合総会決議217(III))。正式名称は、人権に関する世界宣言。

2 How to Think and Do Macroeconomics 18

2.1 Introduction 18

2.2 Thinking in a Macroeconomic Way 19

2.3 What Should a Macroeconomic Theory be Able to Explain? 22

Real GDP growth 22

Unemployment 23

Real wages and productivity 25

Private sector indebtedness 26

Central bank balance sheets 26

Japan’s persistent fiscal deficits: the glaring counterfactual case 27

2.4 Why is it so Difficult to Come to an Agreement on Policy? The Minimum Wage Debate 31

2.5 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions 32

Conclusion 34

References 35

Chapter 2 Appendix: The Buckaroos model 36

Implications of the Buckaroos model 37

^

2マクロ経済学の考え方とやり方18

2.1はじめに18

2.2マクロ経済的な考え方19

2.3マクロ経済理論は何を説明できなければならないのか22

実質GDP成長率22

失業者23

実質賃金と生産性25

民間部門の債務26

中央銀行バランスシート26

日本の持続的な財政赤字:明白な反事実的なケース27

2.4なぜ政策協定にたどり着くのが難しいのか?最低賃金ディベート31

2.5科学革命の構造32

結論34

参考文献35

第2章付録:バッカルーモデル36

バッカルーモデルの意味 37

#2:25,35 Kaldor "A Model of Economic Growth", 1957, EJ

① 生産の総量と労働生産性は趨勢的に一定の率で持続的に成長すること,

② ①と関連して労働者一人当たりの資本量は持続的に増加すること,

③ 発展した資本主義社会では資本利潤率は安定し,優良債券の利回りで示される純長期利子率よりこの利潤率は高いこと,

④ 長期的に資本・産出比率は安定していること,

⑤ 所得中の利潤の分け前と産出高中の投資の割合に強い相関関係があること,

⑥ ④と⑤は成長率の異なる国々にも当てはまること」(Kaldor 1958e, pp.2-3:訳pp.32-33)。これらの①~⑥は,国民所得における“利潤の分け前”と“資本・産出高の比率の一定性”を見るならば,“利潤率が一定である”という意味を持つ。カルドアは,この「定型化された事実」を説明するために,「技術進歩関数(Technical Progress Function)」という新たな分析装置を用いて,技術こそ経済成長の最大の要因である,と述べた。

カルドア(Nicholas Kaldor, 1908 - 1986):メモ

http://nam-students.blogspot.jp/2015/08/blog-post_23.html

『経済安定と成長』、中村至朗訳、大同書院、1964年 カルダー は入手困難

#2:27,28

ビル・ミッチェル教授 MMTに被害妄想な日本の財務大臣(&メモ)

われわれの新しいMMT教科書 - マクロ経済学 - (Macmillan発行、2019年3月)のタイトルは「マクロ経済学をどのように考え、実行するか」、だが、その第2章は、「マクロ経済学理論が説明すべきものは何か」とした。その中で我々は「日本の持続的財政赤字:明らかに事実に反するケース」を議論している。

われわれはこう書いた。[#2:27~8]

他のほとんどのマクロ経済学の教科書では、何らかの形で以下の命題が否定できない事実として記載されていることがわかる。

1.持続的な財政赤字は短期金利を押し上げる。高まる財政赤字をファイナンスするニーズから、供給に対して乏しくなる貯蓄の需要が高まるからだ

2. この金利の上昇が民間投資支出を弱める(いわゆる「クラウドアウト」仮説)。

3. 持続的な財政赤字は債券市場に国債利回りの上昇圧力をもたらす

4. 持続的な財政赤字に伴う公的債務対GDP比の上昇により、いつか債券市場は政府への貸付を減らし、政府の資金繰りを苦しくする

5. 持続的な財政赤字はインフレを加速し、潜在的にハイパーインフレの可能性を高める。これはマクロ経済にとって非常に有害なものだ。

「(MMTの主張は)全部知っていた」という連中、「MMTはクレイジー」という連中は、これら五つの主流命題がすべて日本が提供する現実によって反証されているという事実に向き合わねばならないだろう。

ビル・ミッチェル教授 MMTに被害妄想な日本の財務大臣

さりげなく国債廃止もちゃんと言っているミッチェル先生

[クライテリオン2019/9に別訳]

#2:29,30 The government is the last borrower left standing billThursday, August 5, 2010

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2019/07/httpbilbo_18.html

The government is the last borrower left standing

#2:29,30関連

【日本政府の長期債務残高(左軸)[青]と長期金利(右軸)[赤]】

#2:32,35

McCloskey, D.(1985) The Rhetoric of Economics,

ケルトン教授2 (レトリックについて)

参考:

ミッチェルのレンズの比喩 Mitchell-lens

(レンズの比喩は本書では使われていない。#8:128も参照。)

#2:32~33トーマス・クーン Thomas Kuhnの1962年の本 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions(邦題:科学革命の構造)

3 A Brief Overview of Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism 38

3.1 Introduction 39

3.2 An Introduction to Monetary Capitalism 39

3.3 Tribal Society 40

3.4 Slavery 41

3.5 Feudalism 42

3.6 Revolts and the Transition to Capitalism 43

3.7 Capitalism 44

3.8 Monetary Capitalism 45

3.9 Global Capitalism 46

3.10 Economic Systems of the Future? 47

Conclusion 49

References 49

^

3経済史と資本主義の台頭の概要38

3.1はじめに39

3.2貨幣資本主義の紹介39

3.3部族社会40

3.4奴隷制41

3.5封建主義42

3.6反乱と資本主義への移行43

3.7資本主義44

3.8貨幣資本主義45

3.9グローバル資本主義46

3.10将来の経済システムは? 47

結論49

参考文献49

#3:45 Why the financial markets are seeking an MMT understanding – Part 2 billTuesday, July 2, 2019

共産党宣言

#3:46

M→C→M'

(→#11:177、

#26:422、

Mitchell2019#26:422 Marx

NAMs出版プロジェクト: AIMN Interview: Bill Mitchell – an unreasonable man EdwardEastwoodAugust 8, 2015

ゴータ綱領批判

4 The System of National Income and Product Accounts 50

4.1 Measuring National Output 50

4.2 Components of GDP 53

Consumption (C ) 53

Investment (I) 53

Government spending (G) 54

Exports (X) minus imports (M) or net exports (NX) 54

4.3 Equivalence of Three Measures of GDP 54

Expenditure approach 55Production approach 55

Income approach 55

4.4 GDP versus GNP 55

4.5 Measuring Gross and Net National Income 56

Measuring net national income 56

4.6 GDP Growth and the Price Deflator 57

4.7 Measuring Chain Weighted Real GDP 58

4.8 Measuring CPI Inflation 59

The CPI Index 59

Rate of growth of the CPI index 61

Difficulties in using the CPI to accurately measure inflation 62

4.9 Measuring National Inequality 63

Conclusion 65

References 65

^

4国民所得と製品勘定のシステム50

4.1国家生産高の測定50

4.2 GDPの構成要素53

消費量(C)53

投資(I)53

政府支出(G)54

輸出(X)マイナス輸入(M)または純輸出(NX)54

4.3 GDPの3つの尺度の等価性54

支出アプローチ55生産アプローチ55

所得への取り組み55

4.4 GDP対GNP 55

4.5国民総所得および純国民所得の測定56

純国民所得の測定56

4.6 GDP成長率と価格デフレーター57

4.7チェーン加重実質GDPの測定58

4.8 CPIインフレの測定59

CPI指数59

CPI指数の成長率61

正確にインフレを測定するためにCPIを使用することの困難

4.9国民格差の測定63

結論65

参考文献65

#4:51~2,65 Sex, drugs and GDP - National accounts

5 Labour Market Concepts and Measurement 66

5.1 Introduction 66

5.2 Measurement 67

Labour force framework 67

Impact of the business cycle on the labour force participation rate 71

5.3 Categories of Unemployment 72

5.4 Broader Measures of Labour Underutilisation 73

5.5 Flow Measures of Unemployment 75

Labour market stocks and flows 77

5.6 Duration of Unemployment 78

5.7 Hysteresis 80

Conclusion 81

References 82

^

5労働市場の概念と測定66

5.1はじめに66

5.2測定67

労働力の枠組み67

景気循環が労働力参加率に与える影響71

5.3失業のカテゴリ72

5.4労働の十分に活用されていないためのより広範な措置73

5.5失業者のための流動対策75

労働市場の株式およびフロー77

5.6失業期間78

5.7ヒステリシス80

結論81

参考文献82

#5 ILO

#5:69

Saturday Quiz – March 13, 2010 – answers and discussion

2013/3/13

6 Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds 83

6.1 Introduction 83

6.2 The Sectoral Balances View of the National Accounts 84

Introduction 84

How can we use the sectoral balances framework? 86

A graphical framework for understanding the sectoral balances 87

6.3 Revisiting Stocks and Flows 91

Flows 91

Stocks 92

Inside wealth versus outside wealth 93

Non-financial wealth (real assets) 94

6.4 Integrating NIPA, Stocks, Flows and the Flow of Funds Accounts 94

Causal relationships 96

Deficits create financial wealth 96

6.5 Balance Sheets 97

6.6 The Flow of Funds Matrix 101

Flow of funds accounts and the national accounts 102

Conclusion 103

References 103

^

6部門別会計と資金の流れ83

6.1はじめに83

6.2国民経済計算のセクター別収支ビュー84

はじめに84

セクター別バランスの枠組みをどのように使用できますか。 86

部門別収支を理解するための図式的枠組み87

6.3株式とフローの見直し91

フロー91

在庫92

内側の富と外側の富93

非金融資産(実資産)94

6.4 NIPA、株式、フローおよび資金勘定のフローの統合94

因果関係96

赤字は経済的富を生み出す96

6.5バランスシート97

6.6資金マトリックスの流れ101

資金勘定と国民経済計算の流れ102

結論103

参考文献103

#6 Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

#6:87

6.2グラフィカルな部門別収支フレームワーク

88:

6.3民間の国内黒字と赤字

89:

6.4主権政府のための持続可能な空間

90:

6.5財政規則によって制約された政府のための持続可能な空間

財政赤字より少ない

GDPの3%

6.2 グラフィカルな部門別収支フレームワーク

#6:87:

6.2 A graphical sectoral balances framework

Fiscal surplus /

(G-T)<0 /Private

| / domestic

| / balance

| / (S=I)

| /

| /

| /

| /

External | / External

deficit |/ surplus

ーーーーーーーーーーーーXーーーーーーーーーーーーー

CAB<0 /| CAB>0

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ Fiscal deficit

/ (G-T)>0

したがって、我々はこの知識を一般化し、縦軸の両側の45 0線より上のすべての点が民間の国内部門の赤字に対応し、縦軸の両側の45 0線より下のすべての点が民間の国内部門の黒字に対応すると結論づけることができる。 。

図6.7bはこの結論をグラフィカルに表現しています。

6.3民間の国内黒字と赤字

88:

6.3 Private domestic surpluses and deficit

_______________________

| Fiscal surplus /|

| (G-T)<0 /Private

| | / domestic

| Private | / balance

| domestic | / (S=I)

| deficit | / |

| (S-I)<0 | / |

| | / |

| | / |

External | / External

deficit |/ surplus

|ーーーーーーーーーーーXーーーーーーーーーーー|

CAB<0 /| CAB>0

| / | |

| / | |

| / | Private |

| / | domestic |

| / | surplus |

| / | (S-I)>0 |

| / | |

| / Fiscal deficit |

| / (G-T)>0 |

|/__________|___________|

改変:

_______________________

|赤字 Fiscal surplus /|

| (G-T)<0 /Private

| | / domestic

| Private / balance

| domestic / (S=I)

| deficit / |

| (S-I)<0 / |

| | / |

| | / |

External | / External

deficit |/ surplus

|ーーーーーーーーーーーXーーーーーーーーーーー|

(X-M)<0 /| (X-M)>0

| / | |

| / | |

| / Private |

| / domestic |

| / surplus |

| / (S-I)>0 |

| / | |

| / Fiscal deficit |

| / (G-T)>0 黒字|

|/__________|___________|

自国通貨発行政府にとっては、4象限のどの点でも許容されます。 民間部門の支出と貯蓄の決定が、国民所得を牽引する対外部門との貿易から生じる収入の流れと相まって、完全な雇用と物価の安定を維持するために必要な規模に政府部門のバランスを調整させることができます。

図6.8Δは、自国通貨を発行する政府が利用可能な持続可能な空間として定義できるものを示しています。

89:

6.4 Sustainable space for sovereign governments

Fiscal surplus /|

(G-T)<0 / |Private

| / |domestic

| / |balance

| / | (S=I)

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

External | / | External

deficit |/ | surplus

ーーーーーーーーーーーーXーーーーーーーーーーー+ーー

(X-M+FNI)<0/| |(X-M+FNI)>0

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ | |

/ーーーーーーーーーー+ーーーーーーーーーーー┛

Fiscal deficit

(G-T)>0

the net external income flows (FNI)

純外部所得フロー(FNI)

#6:94

L. S. Ritter, “An Exposition of the Structure of the Flow-of-Funds Accounts,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 18, May 1963.

Chapter 6 Sectoral Accounting

In Chapter 5 the national accounting framework was outlined out in some detail. The framework provides a means for measuring the economic activity in an economy over a period of time and allows us to consider the sources of expenditure that drive national income and output. In this chapter we consider economic activity from a different perspective.

To start the discussion, recall the distinction between stocks and flows. In a monetary economy, flows of expenditures measured in terms of dollars spent over a period involve transactions between sectors in the economy, which also have logical stock counterparts. There are two related frameworks that economists use to account for these transactions.

The national accounting framework and the so-called flow-of-funds accounts are two different, but related ways of considering national economic activity.

[NOTE: SOME MORE BACKGROUND HERE TO COME – DETAILING HOW JOINING THESE FRAMEWORKS ALLOWS US TO EXPLICITLY UNDERSTAND THE MONETARY SIDE OF THE ECONOMY]An early exponent of the flow-of-funds approach, Lawrence Ritter wrote in 1963 that:

The flow of funds is a system of social accounting in which (a) the economy is divided into a number of sectors and (b) a “sources- and-uses-of-funds statement” is constructed for each sector. When all these sector sources-and-uses-of-funds statements are placed side by side, we obtain (c) the flow-of-funds matrix for the economy as a whole. That is the sum and substance of the matter.

[Full reference: Ritter, L.W. (1963) ‘An Exposition of the Structure of the Flow-of-Funds Accounts’, The Journal of Finance, 18(2), May, 219-230]The flow-of-funds accounts allow us to link a sector’s balance sheet (statements about stocks of financial and real net wealth) to income statements (statements about flows) in a consistent fashion. That is flows feed stocks and the flow-of-funds accounts ensure that all of the monetary transactions are correctly accounted for.

第6章セクター別会計

[ブログの]第5章では、国内会計の枠組みがある程度詳細に概説された。この枠組みは、ある期間にわたる経済の経済活動を測定するための手段を提供し、国民の収入と産出を推進する支出の原因を検討することを可能にします。この章では、経済活動を異なる観点から考察します。

議論を始めるために、株式とフローの違いを思い出してください。通貨経済では、ある期間に費やされたドルの観点から測定された支出の流れは、経済のセクター間の取引を含みます。経済学者がこれらの取引を説明するために使用する2つの関連フレームワークがあります。

国内会計の枠組みといわゆる資金の流れの会計は、2つの異なる、しかし全国経済活動を考慮する関連した方法です。

[注:今後のいくつかの背景 - これらのフレームワークをどのように結合するかを詳細に説明することで、米国が経済の正当な側面を明確に理解できるようにする]

資金の流れのアプローチの初期の解説者であるLawrence Ritterは、1963年に次のように書いています。

資金の流れは、(a)経済がいくつかの部門に分割され、(b)各部門について「資金の源泉と使用の声明」が作成される社会会計のシステムです。これらの部門別の出資元および使用方法の声明を並べて表示すると、(c)経済全体の資金の流れの行列が得られます。それが問題の合計と内容です。

[全参考文献:Ritter、L。 (1963)「資金の流れの口座の構造の博覧会」、財政のジャーナル、18(2)、5月、219-230]

資金の流れの勘定科目は、私たちがセクターの貸借対照表(財務および実質純資産の株式に関する声明)を損益計算書(フローに関する声明)に一貫した方法でリンクすることを可能にします。つまり、フローは在庫をフィードし、資金のフロー勘定はすべての金銭取引が正しく会計処理されるようにします。

以下の方がまとまっている

2015/11/24

#6:94 Sectoral balances – Part 1

6.5 財政規則によって制約された政府のための持続可能な空間

90:

6.5 Sustainable space for governments constrained by fiscal rules

Fiscal surplus /|

(G-T)<0 /Private

| / domestic

| / balance

| / (S=I)

| / |

| / |

| / |

| / |

External | / External|

deficit |/ surplus |

ーーーーーーーーーーーーXーーーーーーーーーーー+ーー

(X-M+FNI)<0/|(X-M+FNI)>0|

//| |

///| |

////| |

ーーーーーーー/ーーーー|ーーーーーーーーーーー┻ーー

/ -3% | Fiscal Rule:

/ | Fiscal deficit LESS THAN

/ | 3% of GDP

/ Fiscal deficit

/ (G-T)>0

/

#6:94 Sectoral balances – Part 1,2,3(書籍Mitchell2019#6では3が先。3,1,2の順。)

#6:94

L. S. Ritter, “An Exposition of the Structure of the Flow-of-Funds Accounts,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 18, May 1963.

The flow of funds is a system of social accounting in which (a) the economy is divided into a number of sectors and (b) a “sources- and-uses-of-funds statement” is constructed for each sector. When all these sector sources-and-uses-of-funds statements are placed side by side, we obtain (c) the flow-of-funds matrix for the economy as a whole. That is the sum and substance of the matter.

資金の流れは、(a)経済がいくつかの部門に分割され、(b)各部門について「資金の源泉と使用の声明」が作成される社会会計のシステムです。これらの部門別の出資元および使用方法の声明を並べて表示すると、(c)経済全体の資金の流れの行列が得られます。それが問題の合計と内容です。

#6:95

Understanding what the T in MMT involves – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

2018/9/20

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=40383

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2019/06/understanding-what-t-in-mmt-involves.html

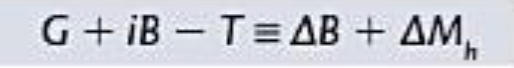

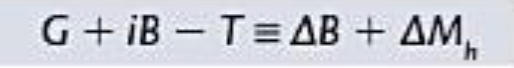

部門別均衡の式を次のように書き出すと、

[(S - I) - CAD] =(G - T) [#6:95]

左側の([S - I] - CAD)という用語は非政府部門の財政収支であり、政府の財政収支と同じで反対の符号であることを私たちは知っています。

したがって、(G - T)> 0(財政赤字)の場合、[(S - I) - CAD]> 0(非政府余剰)である必要があります。

さらに、(G - T)が増加すれば(つまり財政赤字が大きければ)、非政府余剰は増加しなければならない。

これらの命題は定義上正しい。

さらに、経常収支赤字があり(CAD <0)、国内の民間部門が全体的に節約し始めた場合(S - I> 0)、政府の赤字が大きくならなければならない。政府支出、それから国民の収入は落ち、財政赤字はさらにもっと大きくなるでしょう。

この記述は、固有の部門別収支会計を超えています。

#6:98~100

part1

Figure 6.1 A stylised sectoral balance sheet

The balance sheet depicts stocks but we can easily see how they might provide us with information about flows, in the way the national accounts does. A stock is measured at point in time (say, the end of the year) whereas flows measure monetary transactions over a period (say, a year).

If we examine the difference between a balance sheet compiled at, say December 31, 2011, and a balance sheet compiled at December 31, 2012, we will be able to represent the information in the balance sheet about assets, liabilities and net worth as flow data.

Consider Figure 6.2 (where the Δ symbol refers to changes over the period concerned). Now the entries in the T-account denote uses and sources of funds (that is, flows) over the period of interest. There are two components. One relates to financial assets and the other real assets and net worth.

A given sector (for example, household, firm, government) can obtain funds by increasing their liabilities by borrowing and incurring debt (ΔL). They can apply those funds to accumulating more financial assets (ΔFA) or building cash balances (ΔM)

If we wanted to complicate matters we could decompose – ΔFA, ΔM) and ΔL – further, by recognising that a given sector can also sell existing financial assets or run down cash balances to obtain new funds. Similarly, it might use funds to reduce liabilities (run down debts). So the entries in Figure 6.2 are to be considered net transactions.

Figure 6.2 A uses-and-sources-of-funds statement

The second source and use of funds for a sector relates to changes in Real assets (ΔRA) and the change in Net worth (ΔNW) over a given period.

In the National Accounts framework we considered the division between the Capital Account and the Current Account, where the former related to investment in productive capacity and the latter refered to recurrent spending and income. The Capital Account measured transactions, which change the real assets held and the net worth of the economy.

What do we mean by a change in real assets? In the National Accounts, we considered gross capital formation or investment, which is defined as expenditure on productive capital goods (for example, plant and equipment, factories etc). This is a use of funds by firms in the current period. In Chapter 12, we consider the difference between gross and net investment when we discuss the concept of depreciation. For now though we abstract from that real world complexity.

Finally, we consider the change in net worth for a sector in a given period is the residual after all the uses and sources of funds have been accounted for. From an accounting perspective, net worth is equal to the difference between total assets and total liabilities.

It follows that a change in net worth over the period of interest is equal to the difference between the change in total assets and the change in total liabilities.

If total assets increase by more (decrease by less) than total liabilities increase (decrease) then the net worth of the sector has risen.

Another way of thinking about the change in net worth, which is a flow of funds, is to link it to the National Accounts concept of saving.

In the National Accounts framework, we consider household saving, for example, to be the difference between consumption (a use) and disposable income (a source). This concept generalises (with caution) to the statement that the surplus of a sector is the difference between its current revenue and its current expenditure.

What happens to the flow of surplus funds? If the current flow of income is greater than the current expenditure, then at the end of the period, the sector would have accumulated an increased stock of total net assets – either by increasing the actual assets held and/or reducing liabilities owed.

The surplus between current income and current expenditure has to be matched $-for-$ by an increase in the stock of total net assets. We have already discussed total net assets above but in different terms.

We defined the change in net worth over a period as the difference between the change in total assets and the change in total liabilities. That difference is exactly equal to the surplus between current income and current expenditure.

Thus, from an accounting perspective, we can consider saving to be the change in net worth over a period.

Figure 6.2, however, only implicitly includes the the current account transactions – the flow of current income and expenditure – inasmuch as we have defined the change in net worth (ΔNW) to be the difference between the two current flows.

The simplicity of Figure 6.2, however, makes clear an essential insight – if a sector is running a deficit (that is, it is spending more than it is earning or in the parlance used above, it is investing more than it is saving) then it must obtain the deficit funds from its available sources:

- Increased borrowing

- Running down cash balances

- Selling existing financial assets

Conversely, a sector that it running a surplus (that is, it is spending less than it is earning or in the parlance used above, it is investing less than it is saving) must be using the surplus funds to:

- Repay debt

- Build up cash balances

- Increase its financial assets (increasing lending)

We also have to be cautious in our terminology when considering the different sectors. If we are considering the household sector, then it is clear that if they spend less than their income and thus save they are deferring current consumption in the hope that they will be able to command greater consumption in a future period.

The increase in their net worth provides for increased future consumption for the household.

Similarly, for a business firm, if they are spending less than they are earning, we consider them to be retaining earnings which is a source of funds to the firm in the future.

We consider the private domestic sector as a whole (the sum of the households and firms) to be saving overall, if total investment by firms is less than total saving by households. From the National Accounts, we consider that households save and firms invest.

However, in the case of the government sector such terminology would be misleading. If the government spends less than they take out of the non-government sector in the form of taxation we say they are running a budget surplus. A budget deficit occurs when their spending is greater than their taxation revenue.

But a budget surplus does not increase the capacity of the government to spend in the future, in the same way that a surplus (saving) increases the capacity of a household to spend in the future.

As we saw in Chapter 3, a sovereign, currency-issuing government faces no intrinsic financial constraints, and can, at any time, purchase whatever is for sale in the currency it issues. It capacity to do so is not influenced by its past spending and revenue patterns.

Figure 6.3 provides the most comprehensive framework for analysing the flow-of-funds because it brings together the current transactions (income and expenditure), the financial transactions, and the capital transactions that we have dealt with earlier. The capital and financial transactions are captured in changes to the balance sheet (Figure 6.1)

Figure 6.3 A complete sector uses-and-sources-of-funds statement

The transactions above the dotted line comprise the income statement and record current expenditure (uses) and current revenue (sources). The balancing item above the dotted line is the change in net worth (ΔNW) or “saving”.

The changes in the balance sheet are shown below the dotted line and the balancing item is once again, the change in net worth (ΔNW).

The changes in the balance sheet are shown below the dotted line and the balancing item is once again, the change in net worth (ΔNW).

You can see that we could cancel out the change in net worth (ΔNW), which is the balancing item in both the income statement and the change in the balance sheet. This would leave is with the accounting statement that that sources of funds to a sector through current income and borrowing must as a matter of accounting be used – for current expenditures, investment, lending, and/or building up cash balances.

図6.1様式化された部門別バランスシート

貸借対照表には株式が表示されますが、国民経済計算と同様に、それらがどのようにフローに関する情報を提供してくれるのかが簡単にわかります。在庫は特定の時点(年末など)で測定されますが、フローは一定期間(1年など)にわたる通貨取引を測定します。

2011年12月31日に作成された貸借対照表と、2012年12月31日に作成された貸借対照表との差異を調べると、資産、負債および純資産に関する貸借対照表の情報をフローとして表すことができます。データ。

図6.2を検討してください(ここで、Δ記号は関係する期間にわたる変化を表します)。 これで、Tアカウントのエントリは、関心のある期間にわたる資金の使用と供給元(つまりフロー)を表します。 2つの要素があります。 一つは金融資産に関するもので、もう一つは実物資産と純資産に関するものです。

特定のセクター(家計、企業、政府など)は、借金をして借金をすることで負債を増やすことで資金を調達できます(ΔL)。 彼らはより多くの金融資産の蓄積(ΔFA)または現金残高の構築(ΔM)にそれらの資金を適用することができます

さらに、特定のセクターが既存の金融資産を売却したり、新しい残高を得るために現金残高を減らしたりできることを認識することで、分解可能な事項(ΔFA、ΔM)およびΔLを複雑にしたい場合。 同様に、それは負債を減らすために資金を使うかもしれません(借金を減らす)。 そのため、図6.2のエントリは純取引と見なされます。

新しい資産を得るために、金融資産または現金残高を減らします。同様に、それは負債を減らすために資金を使うかもしれません(借金を減らす)。そのため、図6.2のエントリは純取引と見なされます。

図6.2資金使途声明書

セクターのための資金の第2の源と使用は、与えられた期間にわたる実物資産の変化(ΔRA)と純資産の変化(ΔNW)に関連しています。

国民経済計算の枠組みでは、資本勘定と当座預金の間の分割を考慮しました。前者は生産能力への投資に関連し、後者は経常支出と所得に関連していました。資本勘定は取引を測定し、それが保有する実物資産と経済の純資産を変えます。

実物資産の変化とはどういう意味ですか?国民経済計算では、総資本形成または投資を考慮しました。これは、生産的資本財に対する支出と定義されています(たとえば、プラントと設備、工場など)。これは当期の企業による資金の使用です。第12章では、減価償却の概念について説明するときに、総投資と純投資の違いを検討します。今のところ私たちはその現実世界の複雑さから抜粋します。

最後に、ある期間におけるあるセクターの純資産の変動は、すべての用途と資金の源泉が計上された後の残余であると考えます。会計の観点からは、純資産は総資産と総負債の差に等しい。

つまり、利息期間における純資産の変動は、資産合計の変動と負債合計の変動との差に等しいということになります。

総資産が負債総額の増加(減少)よりも増加(減少)する場合、そのセクターの純資産は上昇しています。

資金の流れである純資産の変化について考えるもう一つの方法は、それを国民経済計算の貯蓄という概念に結び付けることです。

国民経済計算の枠組みでは、たとえば家計貯蓄は、消費(用途)と可処分所得(出所)の差と考えています。この概念は、セクターの余剰が現在の収入と現在の支出の差であるというステートメントに(注意して)一般化します。

余剰資金の流れはどうなりますか?現在の収入の流れが現在の支出を上回っている場合、期間の終わりに、セクターは、保有する実際の資産を増やすことおよび/または負う負債を減らすことによって、純資産合計の増加した在庫を累積していたでしょう。

当期利益と当期支出との間の剰余金は、純資産総額のストックの増加により、対ドルで一致させる必要があります。純資産合計については上記で説明しましたが、異なる用語で説明しました。

一定期間にわたる純資産の変動を、資産合計の変動と負債合計の変動の差と定義した。その差は、現在の所得と現在の支出との間の剰余に正確に等しい。

したがって、会計の観点からは、貯蓄はある期間にわたる純資産の変化であると考えることができます。

ただし、純資産の変動(ΔNW)を2つの経常収支の差と定義しているため、図6.2には経常収支の取引 - 当期の収支の流れ - が暗黙のうちに含まれています。

しかし、図6.2の単純さは本質的な洞察を明らかにします - セクターが赤字を走っているならば(すなわち、それが収入を上回っているか上の用語で使われているのなら)それは利用可能な情報源から赤字資金を得なければならない:

借入金の増加

現金残高の減少

既存の金融資産の売却

逆に、それが黒字を実行している(つまり、それが稼いでいるよりも少ない支出である、または上で使用されている用語では、節約しているよりも少ない投資である)セクターは、余剰資金を使用しなければなりません。

借金を返済する

現金残高を増やす

金融資産を増やします(貸付を増やします)。

また、さまざまな分野を検討する際には、専門用語に注意する必要があります。私たちが家計部門を考えているのであれば、彼らが彼らの収入よりも少なく費やして節約すれば、彼らが将来のより大きな消費を命じることができることを期待して現在の消費を延期していることは明らかです。

彼らの純資産の増加は世帯のための増加した将来の消費に備える。

同様に、事業会社にとって、彼らが稼いでいるよりも少ない支出であるならば、私たちは彼らが将来会社への資金の源である収益を保持していると考えます。

企業による総投資が世帯による総貯蓄よりも少ない場合、国内の民間部門全体(家計と企業の合計)が全体的に貯蓄していると考える。国民経済計算から、家計は貯蓄し、企業は投資すると考えています。

しかし、政府部門の場合、そのような用語は誤解を招くでしょう。政府が支出よりも支出が少ない場合

課税の形での非政府部門のうち、我々は彼らが予算黒字を実行していると言う。彼らの支出が彼らの課税収入よりも大きいときに予算の赤字が発生します。

しかし、余剰(貯蓄)が将来の世帯の支出能力を増加させるのと同じように、予算の黒字が将来の政府の支出能力を増加させることはない。

第3章で見たように、主権の通貨発行政府は本質的な財政上の制約に直面せず、いつでも、発行する通貨で売られるものは何でも購入することができます。その能力は、過去の支出や収益のパターンに左右されません。

図6.3は、資金の流れを分析するための最も包括的な枠組みを示しています。これは、現在の取引(収支)、金融取引、および以前に処理した資本取引をまとめるためです。資本取引と金融取引は、貸借対照表への変更として記録されます(図6.1)。

図6.3完全な部門の使用および資金源の声明

[#6:100に対応]

点線より上の取引は、損益計算書を構成し、現在の支出(用途)と現在の収益(出所)を記録します。点線より上のバランス項目は、純資産の変化(ΔNW)または「節約」です。

貸借対照表の変動は点線の下に表示され、貸借対照表の項目はまたもや純資産の変動(ΔNW)です。

損益計算書と貸借対照表の両方の変動項目である純資産の変動(ΔNW)を相殺することができることがわかります。これは、経常収支、投資、貸付、および/または現金残高の積み上げのために、経常利益および借入を通じた部門への資金の出所を会計の問題として使用しなければならないという会計報告と一緒に残されるでしょう。

…

part2

Figure 6.4 (taken from Ritter, 1963) shows three sectors and the total economy. At the most aggregate level, the three sectors could be the private domestic sector, the government sector and the external sector.

Figure 6.4 A stylised three-sector Flow-of-Funds Matrix

For each period being accounted for, the statistician would record the flows on funds that related to each of the row categories in the matrix. Most importantly, we have learned that for every deficit sector, which saves less than it invests, there has to be offsetting surpluses in at least one other sector.

Lawrence S. Ritter (1963) called the Economy-wide Flow-of-Funds Matrix.

図6.4(1963年、Ritterより)は3つのセクターと総経済を示しています。最も集約的なレベルでは、3つのセクターは、国内の民間セクター、政府のセクターおよび外部のセクターになります。

図6.4様式化された3セクターの資金の流れのマトリックス

[#6:101]

会計処理されている期間ごとに、統計学者は、マトリックス内の各行カテゴリに関連する資金にフローを記録します。最も重要なことは、投資額よりも節約できるすべての赤字部門について、少なくとも1つの他の部門の黒字を相殺する必要があるということです。

Lawrence S. Ritter(1963)は、経済全体の資金の流れのマトリックスを呼んだ。

7 Methods, Tools and Techniques 104

7.1 Overview 104

7.2 Basic Rules of Algebra 106

Model solutions 106

7.3 A Simple Macroeconomic Model 107

7.4 Graphical Depiction of a Macroeconomic Model 109

7.5 Power Series Algebra and the Expenditure Multiplier 111

7.6 Index Numbers 112

7.7 Annual Average Growth Rates 115

7.8 Textbook Policy Regarding Formalism 115

Conclusion 117

^

7方法、ツール、およびテクニック104

7.1概要104

7.2代数の基本規則106

モデルソリューション106

7.3単純なマクロ経済モデル107

7.4マクロ経済モデルの図表による描写109

7.5べき級数代数と支出乗数111

7.6インデックス番号112

7.7年間平均成長率115

7.8形式主義に関する教科書の方針115

結論117

#7:107

#7.3,#15? Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output – Bill Mitchell – MMT 2010/10/22

https://nam-students.blogspot.com/2019/06/back-to-basics-aggregate-demand-drives.html

Y = C + I + G + X - M [#7:107]

Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output

もし私たちが外国のセクターを導入したらどうなるでしょうか?同じ論理が適用されます。次の図は、定型化された例を示しています。世帯(単純さのために輸入の唯一の購入者であると仮定される)は今輸入(M)の10ドルまでになります、そしてそれは総需要からの漏れまたは流出を表します。総需要の対応する注入がなければ、経済は縮小するでしょう。この場合、私はインジェクションをインポートと一致するようにエクスポート(X)の形式にすることを許可しました。このようにして、企業は彼らが計画しているすべてのものを世帯(C)、政府(G)、または外国人(X)に売ることができます。

総需要(太い緑色の線)は次のようになります。

Y = C + I + G + X - M [#7:107]

(上の図はブログにあるが本書にはない)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┏━━━━━━━━┓ ┃Government ┃

┃Taxes(T)┃ ┃spending(G)┃

┗━━━━━━━━┛ ┗━━━⬆︎━┳━━━━━┛

⬆︎ ┏━━━━━━━━━━┫ ⬇︎☆

┏┻━⬇︎━━┓ ┏━┻━━┓

┏━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃House┣━━━━➡︎┃ ┃ ┏━━━━━━━━━┓

┃Import(M)┃⬅︎┫hold ┃ ┃Firm┃⬅︎┫Export(X)┃

┗━━━━━━━━━┛ ┃ ┃⬅︎━━━━┫ ┃☆┗━━━━━━━━━┛

┗┳━┳━━┛ ┗⬆︎━━━┛

┃ ┗━━━━━━━━━┛☆ ⬆︎☆

⬇︎Consumption(C)┃

┏━━━━━━┓ ┏━━━━━━━┻━━━━━┓

┃Saving┃ ┃Investment(I)┃

┗━━━━━━┛ ┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━┛

☆=総需要

Y = C + I + G + X - M [#7:107]

┏━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┏━━━━━━━━┓ ┃Government ┃

┃Taxes(T)┃ ┃spending(G)┃

┗━━━━━⬆︎━━┛ ┗━━━━━⬆︎━┳━━━┛

┃ Supply of goods ┃

┃ and services┃ ┃

┃ ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━┫ ┃

┃ ┃ Supply ┃ ┃

┃ ┃ of pro- ┃ ┃☆

┏┻━⬇︎━━┓ ductive┏━┻━⬇︎┓

┏━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃House┣━inputs━➡︎ ┃ ┏━━━━━━━━━┓

┃Import(M)⬅︎━┫hold ┃ ┃Firm⬅︎━┫Export(X)┃

┗━━━━━━━━━┛ ┃ ⬅︎━Payment┫ ┃☆┗━━━━━━━━━┛

┗┳━┳━━┛ of ┗⬆︎━━⬆︎┛

┃ ┃ income ┃ ┃☆

┃ ┗━━━━━━━━━━━━┛☆ ┃

┃ Consumption(C)┃

┏━━━⬇︎━━┓ ┏━━━━━━━┻━━━━━┓

┃Saving┃ ┃Investment(I)┃

┗━━━━━━┛ ┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━┛

☆=総需要

Y = C + I + G + X - M [#7:107]

8 The Use of Framing and Language in Macroeconomics 118

8.1 Introduction 118

8.2 MMT and Public Discourse 119

8.3 Two Visions of the Economy 121

8.4 Cognitive Frames and Economic Commentary 123

8.5 Dominant Metaphors in Economic Commentary 123

8.6 Face to Face: Mainstream Macro and MMT 123

Mainstream Fallacy 1: The government faces the same ‘budget’ constraint as a household 124

Mainstream Fallacy 2: Fiscal deficits(surpluses) are bad(good) 124

Mainstream Fallacy 3: Fiscal surpluses contribute to national saving 125

Mainstream Fallacy 4: The fiscal outcome should be balanced over the economic cycle 125

Mainstream Fallacy 5: Fiscal deficits drive up interest rates and crowd out private investment because they compete for scarce private saving 126

Mainstream Fallacy 6: Fiscal deficits mean higher taxes in the future 126

Mainstream Fallacy 7: The government will run out of fiscal space (or money) if it overspends 127

Mainstream Fallacy 8: Government spending is inflationary 127

Mainstream Fallacy 9: Fiscal deficits lead to big government 128

8.7 Framing a Macroeconomics Narrative 128

Language and metaphor examples 128

Fiscal space 130

Costs of a public programme 130

The MMT alternative framing 131

Conclusion 131

References 132

^

8マクロ経済学におけるフレーミングと言語の使用118

8.1はじめに118

8.2 MMTとパブリックディスコース119

8.3経済の2つのビジョン121

8.4認知的枠組みと経済的コメンタリー123

8.5経済解説における主な比喩123

8.6対面:主流のマクロとMMT 123

主流の誤謬1:政府は世帯と同じ「予算」の制約に直面している124

主流の誤謬2:財政赤字(黒字)は悪い(良い)124

主流の誤謬3:財政黒字は国民の貯蓄に貢献する125

主流の誤謬4:財政結果は経済サイクルにわたってバランスが取れているべきです125

主流の誤謬5:財政赤字は、個人の貯蓄が乏しいことをめぐって競合するため、金利を押し上げ、民間投資を締め出す126

主流の誤謬6:財政

赤字は将来の増税を意味する126

主流の誤謬7:政府は、それが超過した場合、財政の余地(またはお金)を使い果たすだろう127

主流の誤謬8:政府の支出はインフレである127

主流の誤謬9:財政赤字が大きな政府につながる128

8.7マクロ経済学の物語を組み立てる128

言語と比喩の例128

財政スペース130

公共プログラムの費用130

MMT代替フレーミング131

まとめ131

参考情報132

#8

#8:118

#8:121

Don’t Buy It, Anat Shankar-Osorio 2012:

We must reorient our language and with it our thinking from this way of perceiving and interacting with the world to a much more accurate and just one. Earlier, I depicted this tired old economy as overlord model like this:

私たちは自分たちの言語を向き直し、それによって私たちの考えをこの世界からの認識と相互作用からもっと正確でただ一つのものへと変えなければなりません。 以前、私はこの疲れた古い経済をこのような君主モデルとして描いた。

With the help of our new models, we emerge with a new schematic. Here is our relation to the economy when we realign our perception in accordance with what’s true and right in the world.

私たちの新しいモデルの助けを借りて、私たちは新しい回路図で登場します。 世界の真実で正しいことに従って私たちの認識を再調整したときの経済との関係は、次のとおりです。

This image depicts the notion that we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, not how much it will increase the size of the economy.

このイメージは、私たちが、私たちの自然環境と密接に関連しており、それに依存しているという考えを表しています。 経済は私たちのために働いているはずです。 提案された政策が前向きであるかどうかについての判断は、それがどの程度経済の規模を拡大するかではなく、どのように私たちの幸福を促進するかを考慮して検討されるべきです。

私たちの主張の基礎を築く:構築物としての経済

Laying the Foundation for Our Case: The Economy as a Constructed Object

別図が#8:121~2に掲載

MMT補足

ビル・ミッチェル「MMT(現代金融理論)の論じ方」(2013年11月5日) — 経済学101

2018/1/4

ビル・ミッチェル「MMT(現代金融理論)の論じ方」(2013年11月5日) — 経済学101

2018/1/4

ビル・ミッチェル「MMT(現代金融理論)の論じ方」(2013年11月5日)

2013/11/5

Anat Shankar-Osorioは、彼女の本 Don’t Buy Itで、二つの経済モデルを提示した。一つ目のモデルは、以下に示す図で描写されており、彼女はこのモデルが保守的な見方を示すと考えている(実際には進歩的な見方もこのカテゴリーの範疇だが)。

それによれば、現在のイメージは「人と自然は、一義的には経済に貢献するために存在している」(Location 439)。経済は我々から分離され、我々の努力を認識し、その努力に応じて報酬を与える道義的裁定者ということになっている。働かない者や、”経済”の犠牲になった者からは、報酬は奪われることになる。

さらに、もし”政府”がこうした競争的プロセスに介入し、報酬を受けるに値しない態度(怠惰etc)でも報酬を受け取れるような抜け道をもたらしたなら、そのときシステムは機能停止し、”不健康”(経済を生き物と見做すメタファー)に陥るだろう。その解決方法は、経済の自然なプロセスを修復することになるだろう(つまり、最低賃金、雇用保護、所得補償etcといった政府介入を取り除くということ)。

したがって、”自治的かつ自然的”というのが我々の受け取るメッセージということになり、このメッセージに従えば、”政府の’でしゃばり’は良いどころかむしろ有害で、現在の経済的苦難はただただ受容しなければならない”という結論が明確に導かれる。(Location 386)

[#8:121,122]

[People]━━━━━━━━┓

⬇︎

[ECONOMY]

⬆︎

[Nature]━━━━━━━━┛

…

┏━━━━━━━━┓

┃ NATURE ┃

[ECONOMY]━━━➡︎┃[People]┃

┗━━━━━━━━┛

このため、我々の成功は、経済の成功とはある意味独立したものになる。実質GDP成長が強いことが成功している国の品質証明だ。 ”それが大気環境、休暇、平均余命、あるいは幸せといったものを犠牲にして成り立っているかどうか” は無関係だ――”…そうしたものすべては二次的なものになる”。

もし貧困率が上昇しているとしても、それは経済の失敗というより、その人が経済のための活動を十分に行っていないからであって、現在の経済運営で我々にとって十分なことがなされているということになる。

我々が、我々自身の失敗を責められるのだ。貧困率上昇が生じるのは、我々が十分に貢献していないからだということになる。成功している経済に対して標準以下の成功しかしていないなら、どうして報酬を期待することができよう?

進歩的見解もこうした論説に取り込まれており、例えば、緊縮財政論議などにおいても、”より公平な”代替案を提示しようとする。先進国で現在行われている議論を見てみるといい。

どの主要な(進歩的)政党も、緊縮財政ドグマには挑戦しようとしない。あなたは進歩的評論家が以下のようなことを書いているのをたびたび読むことになるだろう… ”我々は、財政赤字が問題で、政府債務は減らさなければならないということは知っているが、もう少し漸進的に行うべきだと思う”。

この点において、両陣営ともに事実上似たり寄ったりの主張をしており、公共的思慮が煙と消えている。その基礎的にある命題が根から枝まで間違っているにもかかわらず、解決策は明瞭だと思われており、価値観体系(保守側にせよ進歩側にせよ)は維持したままに程度問題の議論となっている。

代替理論を目指して

1990年代前半、新自由主義下の信用が高まり始めていた頃、今では現代金融理論(MMT)として広く知られる理論の初期の提唱者たち――それは小さいグループ(Bell/Kelton, Fullwiler, Mitchell, Mosler, Wray)だった――は、過去の異端理論(機能的財政論etc)を利用しつつ、それらに金融システムに特有の運営上の知見を付加し――金融資本主義の運営法についての代替的な論説を発展させようとした。

彼らはそうした論説を通じ、当時目の前にあった「自己制御的市場が万人に対して最大限の富を齎す」という主流派の信条が助長した経済動態が、実は持続不可能であることを明らかにした。

民間負債が積み上がる初期の段階においてさえ、無思慮な金融慣行が生じており、重大な危機が近づいているのは明らかだった。

しかし、他の進歩的経済学者たちは、そうした問題に関心を抱いていなかった。彼らは概してジェンダーやセクシュアリティ、方法論といった問題に注力しており、主流派経済学の論説に対しては、断片的で、容易に退けられるような批判しかしていなかった。

MMTの提唱者によって生み出された言説が進歩的な陣営での地位を上げていくことについての敵意すらあった。

大いなる安定は世界金融危機によって完全な停滞に陥った。世界金融危機は、最初に2007年8月にフランスの銀行であるBNPパリバが、サブプライムローン証券の履行可能性に対する不安の増加による3つの投資銀行からの撤退を凍結したときに始まった。(訳注:要するに、サブプライム証券不安を受けて、投資銀行からの資金引き上げの動きが生じ始めていたときに、BNPパリバが(自行傘下の)投資銀行からの資金引き上げを一方的に凍結した、ということです。)同月の後半に、イギリスのノーザンロック銀行で取り付け騒ぎが発生した。

住宅価格と株価の急落に伴い、大いなる安定の中で積み上げられた富が幻であることが証明され始めた頃に、危機はエスカレートした。2008年9月、リーマンが破綻した。

このとき、自己制御的市場という考えが神話であることが暴かれ、主流派経済学理論の体系全体が信用性を失うことになった――大学で教えられ、研究論文で学術的に用いられる支配的なニューケインジアンモデルは、どれもこの危機を予測できるようにはできていなかったし、危機に対する実行可能な解決法を提示できるものでもなかった。

最終的に、王様は裸だということが明らかになったのだ。

主流派経済学者は当初、とんでもない想定外事象がいくつも生じたにも拘わらず危機に対して沈黙を守った。

危機がエスカレートしてきていた2008年10月23日、前FRB議長(訳注:アラン・グリーンスパンのこと)が米下院の監視・政府改革委員会に姿を現した。当委員会は”金融危機と連邦監督機関の役割”について調査していた。

下院議長のHenry Waxmanはグリーンスパンに対し、後で後悔することになったいくつもの決断を後押ししていたのは自由市場イデオロギーだったのではないかと尋ねた。彼は以下のように答えた:(US House of Representatives, 2008, page 36-37)[#32:527,#8と関連]

グリーンスパン: あー、思い出していただきたいのですが、何にせよ、イデオロギーというのは、人間が現実を扱うための概念上の枠組みなのです。すべての人が持っている。あなたも必ず持っている。生きる上で、あなたがたはイデオロギーを必要としている。問題なのは、持っているイデオロギーが適切か、そうでないかです。私が言いたいのは、そうですね、私の考えに欠陥を見つけたという事です。それがどれくらい重大で、永続的なのかわかりませんが、その事実に私は大変苦悩しておりまして…

Waxman議長:欠陥を見つけたと?

グリーンスパン:どのように世界が機能しているかを定義づける決定的に重要な機能構造だと認識していたモデルに、欠陥を見つけたという事です。言うなれば。

Waxman議長:言い換えれば、あなたの世界観、イデオロギーが、正しくなかったということ、機能しなかったということに気付いたと。

グリーンスパン:その通りです。それがまさに私がショックを受けた理由です。なぜなら、私は40年以上、そのモデルが非常に良く機能しているという相当な根拠を目にしてきたのですから。

しかし、「今回の危機が主流派経済学の役割に対する大いなる試練となった」という認識や、教育カリキュラムや望ましい研究事項を変更する動きも、短命に終わってしまった。

主流派の専門家は、民間の債務危機だったものを国家の債務危機に再構築し始めた。彼らの反政府・自由市場バイアスに適合するように。

危機を醸成させた動態(規制緩和や監督縮小)が解決策であると提唱された。公的な議論は「緊縮財政が唯一の道だ」という主張に溢れ、IMFやOECDのような主導的な国際組織も「大幅な財政緊縮は経済成長を毀損する」という考えを否定する熱烈な予測を立てた。

その後、IMFは自身の計算が間違っていることを認めざるを得なくなった(IMF apology ARTICLE)。

このように、MMTの論説は高度な予測上の価値を持っていたのだが、公共的議論への影響力はゼロに限りなく近かった。

Shenker-Osorio(2012)は経済について以下のような代替的概念を提案している。この概念は、経済が我々の構築物であり、我々から切り離せるものではないという考え方と整合的だ。彼女は以下のように書いている。(Location 1037)

このイメージは、本当に大事なのは、自然環境と密接に関係し依存している我々である概念を描写しています。経済は我々とともに機能するべきなのです。いま政策の是非判断は、それがどれだけ経済のサイズを大きくするかで考えられていますが、これからはその政策がどれだけ我々の幸福に資するかで考えられるべきです。

さらに我々としては「その政策がどれだけ財政赤字や政府債務を増やすか」をも政策の是非の判断材料に加えたい。

彼女の提案は機能的財政論の原則に正しく即している――そこでは経済は”構築物”と見做される――、政策介入は、それらが我々の広範な目標に対してどれだけ機能するかという尺度においてのみ評価されるべきだ、とされている。

だから私たちは、自分たちが何を目標として何を成し遂げたいのかをもっと幅広く正確に定める必要がある。ある一時点の財政赤字というのは無意味な目標だ。

財政バランスは――我々の目標や、政府純支出と目標の間の機能的関係に従って――いかようにもなり得るものだ。

政府は道徳を強化する存在ではないし、経済は道徳活動ではない。

メタファーと価値観

進歩的な文献(例えば、The Common Values Handbook)(訳注:The Common Cause Handbookの間違い? とりあえずそれらしきもの発見できず)では、”我々の態度や行動”に影響を与える”我々の基本規範”となる価値観を明示しようとしている。広範な研究によって、”一貫して生ずる人間的価値観が大量に特定された”。(Common Values Handbook, 2012:8)

この研究を大まかにまとめると、Schwartzの研究と彼の価値観を中心に展開するものだといえる。彼は我々の思考の枠組みとなっている基本で普遍的な10個の人間的価値観を特定した。

我々のビュー―このペーパーで詳説するもの―においては、こうした議論はある種付加的なものだ。そうした価値観は一般的であるため、どんな考えとも整合的なのである。

我々としては、それにいくつかの原則を付け加えることに集中し、その原則を支持する語法を確立していきたい。

…

[課題]

1. 財政バランス

2. 財政赤字

3. 財政黒字

4. 国債

5. 政府支出

6. 政府租税

7. 国民所得

8. 所得保障支出

9. 完全雇用

…

[まず経済学を神の座から引きずり下ろし、自然という神の中に人類を位置づける。スピノザ的]

補記:レンズの比喩は(Mitchell2019)xxiiiに出てくるが本文では展開されない

#8:123,132

ジョージ・P・レイコフ(George P. Lakoff, 1941~ )

1999 with Mark Johnson). Philosophy In The Flesh: the Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books.

マーク・ジョンソン共著、計見一雄訳『肉中の哲学――肉体を具有したマインドが西洋の思考に挑戦する』哲学書房、2004年

心は、そもそも身体的に形成されたものである。

思考は、そのほとんどが無意識的なものである。

抽象概念は、概してメタファーにより構成されている。

The mind is inherently embodied.

Thought is mostly unconcsious.

Abstract concepts are largely metaphorical. (p. 3)

#8:124~8

MMT Primer発売記念! L・ランダル・レイ:「日本はMMTをやっているか?」 – 道草

2019/7/2

…

大きな赤字(負債)比率を生成するためには、醜い方法と良い方法の両方がある。彼らが理解していないのはこのことだ。MMTは長い間これを主張してきたが、理解がほとんど進んでいない。その主な理由は、私たちが平易な英語を使ってきたからだろうか。経済学者は読解が苦手なのだ。彼らにとっては、図と数学は必須だ。ならば以下、彼らの役に立つ書き方をしてみよう。

http://file.erickqchan.blog.shinobi.jp/WrayCurve.PNG

[この図はMitchell2019にはない]

で、名前を付けてみた。ラッファー曲線(Laffer Curve) 、フィリップス曲線 (Phillips Curve) ではないが、名付けてレイ曲線 (Wray Curve) だ。バーでナプキンに描いたのではなく、昨夜寝る前にメモ帳に書いたのだ。

経済が初期状態として点Aにあると仮定する。日本の場合、赤字比率が5%の、成長率が1%というところだ。現在、安倍首相が消費税を課したり米国が景気低迷に陥ったりで日本の成長率は低下するとする。すると経済成長が鈍化し、赤字比率は上昇するにつれ、経済は図の点Bに向かって左に移動する。

成長の鈍化は、家計や企業を脅かし、貯蓄しようと支出を減らし税収を減少させる。成長率の鈍化はまた輸入の減少にもつながり、経常収支はいくぶん「向上」する。部門間収支を見ると、政府収支は赤字(例えば7%の財政赤字)、経常収支は黒字(例えば4から5%)とすると民間部門の黒字は12%(他の二部門の合計)となる。

以上は財政赤字を増やす「醜い」方法。日本式だ。それは、まるで出血させれば病気を治すだろうといつまでも出血させているようなものだ。

MMTの対案とは何か? 企業と家計の自信を回復させることにターゲットを絞った、計測を伴う刺激策だ。老後の生活を保障する社会保障のセーフティーネットの充実。雇用と適正な賃金を確保するためコミットメントを作り直す。労働力の減少に対応するために出生を促進するか、移民を奨励するかする。グリーン・ニューディール政策を実施し、カーボンレスな未来へ移行する。

この場合、点Aから点Cに向かう曲線に沿うことになり、「良い」方法で財政赤字が増加し、成長率は改善する。

但し、赤字の増加は一時的なものであろうことに注意せよ。家計や企業が支出を始めるので、民間黒字が減少する。輸入が増えれば、経常収支の黒字も減る。だから税収が増えるだろう。税率を上げるからではなく、所得が増えるからだ。財政赤字は、国内民間部門の黒字が減少するにつれ減少するだろう。赤字の減少が正確にどの程度になるかは、民間部門の黒字と経常収支の黒字の動向にかかっていて、単にそれらの合計と等しくなる。

上のグラフで言えば、レイ曲線が右にシフトする。点Aの赤字比率における成長率はより高いということになろう。点Aにおける「自然な」赤字比率は存在しない。それは他の二部門の収支次第に依存する。

米国で考えると点Aは、日本と比較すると成長率が高く赤字比率は同程度というところだ。今の米国の経常収支はもちろんマイナスなので、この点では日本より財政赤字率が大きくなる方向。また、どこの成長率をとっても、民間部門の黒字は日本のそれよりも小さく、この点では財政赤字率が小さくなる方向。米国の赤字比率はこの二つの効果が相殺し合い、日本と同程度ので約5%で、成長率は日本より高い。

ここで、「逆ラッファー曲線」のようなものを勧めているのではないことに注意されたい。ラッファー曲線とは、減税は「それ自体を賄う」以上の効果があり、トリクルダウンにより財政赤字を解消するのに十分な歳入増がもたらされるとするものだった。私は、財政支出を増やし経済を刺激すれば税収が増え、赤字比率が元の水準(以下)に戻ると主張しているのではない。実際にどうなるかは、他の二部門の収支に依存している。

財政赤字の大きさそのものは重要ではない。重要なのは、政府の財政政策が公益と民益の追求に役立つかどうかだ。財政赤字の数字は、常に他の二部門との「ぴったりバランス」に常に調整される。この等式は、低すぎる成長率(デフレの)状態でも高すぎる成長率(インフレの)状態でも、どんな成長率になる場合でも成立する。

また、部門間バランス式は、どんな財政赤字比率にも当てはまる。ゆえに、景気刺激策に首尾よく成功すればレイ曲線は右にシフトする可能性が高いのだが、成長率が上昇するにつれ財政赤字比率がどこに落ち着くかを正確に予測することはできない。

このグラフで最も重要なことは、赤字比率がある値だとしても、少なくとも二つの異なる成長率がありえるものとして存在するという理解だ。赤字比率が同じでも、成長率が「醜い」ことになる道もあれば、「良い」ことになる道もある。日本は財政拡大を恐れるあまり、「醜い」赤字を出すための経済を運営し続けている。

財政赤字に関するこの議論の詳細は、新しい教科書のここを参照。 Mitchell, Wray and Watts, Macroeconomics (Macmillan International, Red Globe Press), Chapter 8, 特に pp. 124-128.(訳注 この部分の日本語訳がこちらに)

主流の誤謬1 政府は家計と同じく 「財政」に 制約される

家計になぞらえるのは誤りだ。家計の場合は持っている通貨を使って支出を賄わなければならないが、政府は課税や借り入れに先立って通貨を発行し支出していなければならない。通貨を発行する政府は、収入に制約されることはなく、ソルベンシー・リスクなしに赤字を無制限に維持することができる。

まとめ

• 家計のたとえは通貨発行政府に当てはまらない。

• 政府の支出や収入を、自分の家計の経験から分析しても意味は全くない。

• 政府が通貨を独占しているという特殊性は強調されなければならない。

主流の誤謬2 財政赤字(黒字)は悪い(よい)ことだ…/主流の誤謬3 財政黒字が国民の貯蓄をもたらす…/主流の誤謬4 財政収支は景気循環に関係なく均衡させるべきだ…/主流の誤謬5 財政赤字は金利を上昇させ、民間投資を締め出す。なぜなら民間貯蓄と競合するから…/主流の誤謬6 財政赤字は将来の増税を意味する/主流の誤謬7 政府が支出をし過ぎると財政スペース(もしくは、お金)が枯渇する/…主流の誤謬8 政府支出はインフレ的だ…

主流の誤謬9 財政赤字は大きな政府につながる

財政赤字と政府の規模とは関係がない。たとえ規模の小さな政府であっても、非政府部門全体に貯蓄意欲があり、政府の政策目標が国民所得に対応した完全雇用水準の維持であるならば、継続的に財政赤字を計上する必要がある。

最適な政府の規模は経済理論では決まらない。小さな政府をめざすことは、純粋にイデオロギー上のスタンスであり経済理論に立脚するものではない。政府の規模とは、モノやサービス及びインフラの公的な供給に対する国民の選好を反映したものである。

まとめ

• 政府の規模は決めるのは経済的必要性でなく、政治的な選択であるで。

• いかに小さな政府であっても、完全雇用を維持するために継続的な財政赤字になるのが通常である。

List of Figures

^

図のリスト

図A:

2.1 Comparative unemployment rates, per cent, 1960 to 2017 24

2.2 Real wage and productivity indexes, Australia and USA, 1971 to 2015 (March 1982=100) 26

2.3 Household debt to disposable income ratio, OECD nations, 2000 to 2015 27

2.4 US Federal Reserve Bank monetary base, 1959 to 2015, $US billions 27

2.5 Government fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP, Japan, 1980–2015 28 2.6 Gross and net public debt as a percentage of GDP, Japan, 1980 to 2015 29

2.7 Japan overnight interest rate, per cent, July 1985 to December 2015 30

2.8 Japan government 10 year government bond yield, per cent, 1990 to 2015 30

2.9 Inflation and deflation in Japan, per cent, 1980 to 2015 312 A.1 University Reserve Roo Note 36

^

2.1失業率の比較、1960年から2017年までの割合 24

2.2実質賃金と生産性指数、オーストラリアと米国、1971年から2015年まで(1982年3月= 100)26

2.3家計の負債と可処分所得の比率、OECD諸国、2000年から2015年 27

2.4米国連邦準備銀行のマネタリーベース、1959年から2015年まで、10億米ドル

2.5 GDP比の政府財政収支、日本、1980 - 2015年 28

2.6 1980年から2015年までの日本のGDPに対する割合としての総公債および純公債 29

2.7日本の翌日物金利、1985年7月から2015年12月までの割合 30

2.8日本政府10年国債の利回り、パーセント、1990年から2015年 30

2.9日本のインフレとデフレ、1980年から2015年までの割合 312

A.1大学リザーブRoo Note 36

#2:29,30関連

【日本政府の長期債務残高(左軸)と長期金利(右軸)】

4.1 The Lorenz curve 64

^

5.1 The labour force framework 69

5.2 Labour force participation rate, Australia, 1980 to 2015, per cent 71

5.3 Unemployment rate and average duration of unemployment (weeks), US, February 2008 to October 2012 79

^

5.1労働力の枠組み69

5.2労働力参加率、オーストラリア、1980年から2015年まで、71パーセント

5.3失業率と平均失業期間(週)、米国、2008年2月から2012年10月79 6.1英国の部門別残高、1990年から2017年86

6.1 UK sectoral balances, 1990 to 2017 86

6.2 A graphical sectoral balances framework 87

6.3 Private domestic surpluses and deficits 88

6.4 Sustainable space for sovereign governments 89

6.5 Sustainable space for governments constrained by fi scal rules 90

6.6 A stylised sectoral balance sheet 98

6.7 A uses and sources of funds statement 98

6.8 A complete sector uses and sources of funds statement 100

6.9 A stylised three-sector fl ow of funds matrix 101

^

6.2グラフィカルな部門別収支フレームワーク87

6.3民間の国内黒字と赤字88

6.4主権政府のための持続可能な空間89

6.5財政ルールに制約された政府のための持続可能な空間90

6.6様式化された部門別貸借対照表98

6.7 A用途および財源の声明98

6.8部門別の完全な用途と資金源ステートメント100

6.9資金マトリックス101の様式化された3セクターの流れ

7.1 Consumption function 110

7.2 Slope of consumption function 110

7.3 Employment index numbers, Australia, 2000–15, January 2000=100 114

7.4 Real wages and productivity, 1978–2015, March quarter, 1982=100 115

^

7.1消費機能110

7.2消費関数の勾配110

7.3雇用指数、オーストラリア、2000 - 15年、2000年1月= 100 114

7.4実質賃金と生産性、1978年 - 2015年、1982年3月四半期= 100 115

8.1 The conservative economic construction 121

8.2 The economy is us 122

^

8.1保守的な経済構造121

8.2経済は私たちです122

list of tables

^

テーブルのリスト

表A:

2.1 Average annual real GDP growth by decades, per cent 23

2.2 Average unemployment rates by decade, per cent 23

4.1 Items in Australian CPI, March 2016 59

4.2 Hypothetical data for basket of goods and services 60

4.3 Gini coefficients for several OECD nations, 2004 and 2012 64

5.1 OECD underemployment, per cent of labour force, 1990 to 2015 75

5.2 Labour market flows matrix 76

5.3 Gross flows in the US labour market, December 2015 to January 2016, millions 76

5.4 Total infl ow and outfl ow from labour force states, US, December 2015 to January 2016, millions 77

5.5 Labour market state transition probabilities, US, December 2015 to January 2016 78

7.2 Employment indices for Australia, 2000–12 113 7.3 Compound growth rate calculations 116 8.1 Examples of neoclassical macroeconomic metaphors 124

8.2 Examples of MMT macroeconomic metaphors 131

^

2.1年間の実質GDP成長率の平均数十パーセント、23パーセント

2.2 10年間の平均失業率、23パーセント

4.1 2016年3月のオーストラリアCPIの項目59

4.2商品やサービスのバスケットに関する仮説データ60

4.3いくつかのOECD諸国、2004年および2012年のジニ係数64

5.1 OECDの失業率、労働力のパーセント、1990年から2015年75

5.2労働市場フローマトリックス76

5.3 2015年12月から2016年1月までの米国の労働市場における総フロー、数百万

5.4 2015年12月から2016年1月までの米国の労働力国からの総投資額および支出総額77百万ドル

5.5労働市場の状態遷移の確率、米国、2015年12月から2016年1月78

7.2オーストラリアの雇用指数、2000 - 12 113 7.3複利成長率の計算116

8.1新古典派マクロ経済的比喩の例124

8.2 MMTマクロ経済比喩の例131

箱A:

list of boxes

^

箱のリスト

A

2.1 Challenging neoclassical conventions 33

5.1 The collection and publication of labour market statistics 68

7.1 Rules of Algebra 106

^

2.1困難な新古典主義の慣習33

5.1労働市場統計の収集と公表68

7.1代数の規則106

PART B: CURRENCY, MONEY AND BANKING [#9~10]

(9 Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money/10 Money and Banking)

^

パートB:通貨、通貨、および銀行取引[#9〜10]

(9主権通貨入門:政府とそのお金/ 10お金と銀行業)

In Part B Currency and Banking, we explain why a fiat currency is valued and is acceptable in domestic transac-tions. The distinction between fixed and floating exchange rate regimes and their signifi cance for the conduct of macroeconomic policy is explained. Students are provided with an understanding of how IOUs are created and extinguished (Chapter 9). The focus is money and banking in Chapter 10. The definitions of the money supply and fi nancial assets are outlined. Th e important distinction between the MMT and orthodox representations of the process of credit creation by banks is highlighted. Also, students are introduced to simplifi ed balance sheets, which provide important insights as to the operation of the financial system.

[B]固定相場制と変動相場制との違い、およびマクロ経済政策の実施におけるそれらの意義について説明する。生徒はIOUがどのように作成され消滅するかについての理解を与えられます(第9章)。焦点は、第10章の「お金と銀行業務」です。マネーサプライと金融資産の定義について概説します。 MMTと銀行による信用創造のプロセスの正統的表現との間の重要な違いが強調されている。また、学生は金融システムの運用に関して重要な洞察を提供する単純化されたバランスシートを紹介されます。

9 Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money 134

9.1 Introduction 134

9.2 The National Currency (Unit of Account) 135

One nation, one currency 135Sovereignty and the currency 135

What ‘backs up’ the currency? 136

Legal tender laws 136

Fiat currency 136

Taxes drive the demand for money 137

Financial stocks and flows are denominated in the national money of account 140

The financial system as an electronic scoreboard 140

9.3 Floating versus Fixed Exchange Rate Regimes 140

The gold standard and fixed exchange rates 141

Floating exchange rates 141

9.4 IOUs Denominated in National Currency: Government and Non-Government 142

Leveraging 143

Clearing accounts extinguish IOUs 143

Pyramiding currency 144

9.5 Use of the Term ‘Money’: Confusion and Precision 145

Conclusion 146

References 146

^

9ソブリン通貨入門:政府とその資金134

9.1はじめに134

9.2国内通貨(会計単位)135

1つの国、1つの通貨135の主権および通貨135

通貨を「バックアップ」するものは何ですか。 136

法定入札に関する法律136

フィアット通貨136

税金はお金の需要を促進します137

金融株とフローは国民経済計算勘定で表示されます140

電子スコアボードとしての金融システム140

9.3変動相場制と固定相場制のレジメ140

ゴールドスタンダードと固定為替レート141

変動為替レート141

9.4国内通貨建てのIOU:政府および非政府142

レバレッジング143

清算口座がIOUを消滅させる143

ピラミッド通貨144

9.5「お金」という用語の用法:混乱と精密さ145

まとめ146

参考資料146

PART B: CURRENCY, MONEY & BANKING

9 Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

10 Money and Banking

(これらBは基礎となる考察だがいきなりインルドカーブが出ていて高度だ。本書全体を読み終わったあとまた読み返すべきだろう)

#9:138

#9:139

アダム・スミスの反マネタリスト的言説

関連:

新フィッシャー主義とFTPL - himaginaryの日記

http://d.hatena.ne.jp/himaginary/20170109/EconReporter_Cochrane_interview

インタビュアー

サージェントはこの理論を30年以上前に開発しましたが、主流派にこれまで採用されてこなかったのはなぜでしょうか? 何が最近変わったのでしょうか?

コクラン

実際のところ、FTPLはもっとずっと以前に遡ります。アダム・スミスは次のような素晴らしい言葉を残しています:

税のうち一定割合はある種の紙幣で支払わなければならない、と布告した王子は、それによってその紙幣に一定の価値を与えているのである。(国富論、第2冊)

“A prince who should enact that a certain proportion of his taxes should be paid in a paper money of a certain kind might thereby give a certain value to this paper money.” (Wealth of Nations, Book II)

ということで、基本的な考えはアダム・スミスにあったのです。

すべての貨幣経済学における謎は、「この紙切れのためになぜ我々はこれほど一生懸命に働くのか?」というものです。考えてみれば、それは本当に謎です。あなたも私も一日中額に汗して働き、家に何を持ち帰るのでしょうか? 死んだ大統領の絵が印刷された幾枚かの紙切れです。この小さな紙切れのためになぜ我々はこれほど一生懸命に働くのでしょうか? 誰かがそれを受け取ると知っているからです。しかしなぜその誰かはそれを受け取るのでしょうか? これが経済学の謎です。

FTPLはこの謎に根本的な回答を与えます。その理由というのは、米国では毎年4月15日に税金を払わなければならないからです。そして納税は、まさにその政府貨幣によって行わねばなりません。かつては羊や山羊で納税していた時代もありましたが、今は受け取ってもらえません。彼らは紙幣を取り戻したがっています。ということで、根本的には、貨幣の価値は、政府がそれを税金として受け取ることから生じているのです。

サージェントの研究はそのことを示す上で極めて素晴らしいものでした。しかしミルトン・フリードマンも、金融政策と財政政策の協調について有名な論文を書いています。ということで、ある意味においては、この理論は昔から存在していたのです。問題は、どの程度重きを置くか、ということに過ぎなかったわけです。

Cochrane, John H. (1998) “A Frictionless View of US Ination.” In Ben S. Bernanke and Julio J. Rotemberg. eds. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1998. Cambridge, MA US: MIT Press. pp. 323–334.

Sargent & Wallace (1981)

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent,Neil Wallace (1981)

https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/qr/qr531.pdf

《ある君主が、かれの税の一定部分は一定の種類の紙幣で支はらわれなければならないという、法令をだすとすれば、かれはそうすることによって、この紙幣に一定の価値をあたえうるであろう。》

アダム・スミス『国富論』2:2最終部

世界の大思想上 #9:144~5関連

#9MMT: economics for an economy focussed on meeting the needs of mostpeople

10

10 Money and Banking 147

10.1 Introduction 147

10.2 Some Definitions 147

Monetary aggregates 147

10.3 Financial Assets 148

Yield concepts in fixed income investments 150

10.4 What Do Banks Do? 153

The neoclassical view: the money multiplier 153

MMT representation of the credit creation process 154

Loans create deposits 155

Banks do not loan out reserves 156

Endogenous money 156 [Moore →23:371]

Summary 157

An example of a bank’s credit creation: a balance sheet analysis 157

Conclusion 160

References 161

^

10お金と銀行業務147

10.1はじめに147

10.2いくつかの定義147

通貨の総計147

10.3金融資産148

債券投資における利回り概念150

10.4銀行は何をするのか153

新古典派的見方:貨幣乗数153

クレジット作成プロセスのMMT表現154

ローンは預金を作成する155

銀行は外貨準備を貸し出していません。

まとめ157

銀行の信用創造の一例:バランスシート分析157

結論160

参考文献161

#10:153~

貨幣乗数 the money multiplier

参考:

ビル・ミッチェル「貨幣乗数、及びその他の神話」(2009年4月21日)

Basil J. Moore(1933-2018)

→#23:373

図B:

9.1 The Minsky–Foley pyramid 145

^

9.1ミンスキー - フォーリーピラミッド145

10.1 US Treasury yield curve (3 February 2016) 152

10.2 A typical bank balance sheet 157

10.3 Bank A initial balance sheet 158

10.4 Bank A balance sheet showing loan 158

10.5 Bank A balance sheet showing purchase of car 159

10.6 Bank B balance sheet showing purchase of car 159

10.7 Bank A balance sheet showing loan from central bank 159

10.8 Central bank balance sheet showing loan 159

10.9 Bank A balance sheet showing settlement of debt 160

10.10 Bank B balance sheet showing settlement of debt 160

10.11 Bank A fi nal balance sheet 160

10.12 Bank B final balance sheet 160

10.13 Central bank fi nal balance sheet 160

^

10.1米国財務省利回り曲線(2016年2月3日)152

10.2典型的な銀行の貸借対照表157

10.3銀行A初期貸借対照表158

10.4銀行ローン158を示す貸借対照表

10.5銀行自動車の購入を示す貸借対照表159

10.6自動車159の購入を示す銀行Bの貸借対照表

10.7銀行中央銀行からのローンを示す貸借対照表159

10.8中央銀行の貸借対照表、貸出金を表示しています159

10.9銀行借入金の決済を示すバランスシート160

10.10借入金の決済を示すB銀行の貸借対照表160

10.11銀行A最終貸借対照表160

10.12銀行B最終貸借対照表160

10.13中央銀行決算バランスシート160

9.1 An historical note: Paper notes and redemption taxes in colonial America 138

10.1 Worked Yield Example 150

10.2 The orthodox approach to nominal interest rate determination: the Fisher effect 152

^

9.1歴史的メモ:植民地時代のアメリカにおける紙幣と償還税138

10.1歩留まりの例150

10.2名目金利決定への正統的アプローチ:Fisher効果152

PART C: NATIONAL INCOME, OUTPUT AND EMPLOYMENT DETERMINATION [#11~16] (11 The Classical System

12 Mr Keynes and the ‘Classics’

13 The Theory of Effective Demand

14 The Macroeconomic Demand for Labour

15 The Aggregate Expenditure Model

16 Aggregate Supply)

^

パートC:国民所得、出力および雇用の決定[#11〜16]

(11古典システム

12ケインズ氏と「古典」

13実効需要の理論

14労働に対するマクロ経済的需要

15総支出モデル

16総供給)

In Part C National Income, Output and Employment Determination, a number of models are outlined, begin-ning with the Classical system which still infl uences macroeconomic theory and policy today (Chapter 11). Th is is followed by Keynes’ rebuttal of Classical theory due to major flaws in its analysis of both interest rate and employ-ment determination (Chapter 12) and his demonstration that employment and output depend on expected eff ective demand (Chapter 13). Th e macroeconomic demand for labour is argued to be a derived demand and it is shown that macroeconomic equilibrium can be characterised by unemployment (Chapter 14). Part C concludes with the presentation of the real expenditure model (Chapter 15) and a detailed analysis of mark-up pricing theory which provides a rationale for fi rms acting as quantity adjusters in the short run in the real expenditure model.In Part D Unemployment and Inflation: Theory and Policy, we fi rst defi ne inflation and go on to argue that it emanates from a confl ict over the distribution of income.

パートC国民所得、アウトプットおよび雇用の決定では、古典的なシステムから始まる多くのモデルが概説されていますそれは今日でもマクロ経済理論と政策に影響を及ぼしている(第11章)。ケインズによる古典理論の反論は、金利と雇用決定の両方の分析における大きな問題(第12章)と、雇用と生産が予想される実効需要に依存していることの証明(第13章)によるものである。労働に対するマクロ経済的需要は派生的需要であると主張されており、マクロ経済的均衡は失業によって特徴づけられることが示されている(第14章)。パートCでは、実質支出モデル(第15章)の提示と、実質支出モデルの短期的に数量調整者として機能する企業の理論的根拠を提供する値上げ価格理論の詳細な分析で締めくくっています。そしてインフレ:理論と政策、我々は最初にインフレを定義し、それが所得の分配をめぐる紛争から生じていると主張し続けている。

11 The Classical System 164

11.1 Introduction 164

11.2 The Classical Theory of Employment 165

Why is the labour demand function downward sloping? 167

Why is the labour supply function upward sloping? 167

Equilibrium in the labour market 168

11.3 Unemployment in the Classical Labour Market 169

11.4 What is the Equilibrium Output Level in the Classical Model? 170

11.5 The Loanable Funds Market, Classical Interest Rate Determination 172

11.6 Classical Price Level Determination 175

11.7 Summary of the Classical System 176

11.8 Pre-Keynesian Criticisms of the Classical Denial of Involuntary Unemployment 176

Conclusion 178

References 178

^

11古典的システム164

11.1はじめに164

11.2雇用の古典的な理論165

労働需要関数はなぜ下向きに傾斜しているのか? 167

労働供給機能が上方に傾斜しているのはなぜですか。 167

労働市場における均衡168

11.3古典的な労働市場の失業率169

11.4古典モデルの均衡産出水準は? 170

11.5ローンファンド市場、古典的金利決定172

11.6標準価格レベルの決定175

11.7古典システムの概要176

11.8非自発的失業の古典的否定に対するケインズ前の批判176

結論178

参考文献178

#11:177

(#3:46

M→C→M'、

#26:422、

Mitchell2019#26:422 Marx

#11:118

関連ブログ

同一箇所を幅広く引用

We need to read Karl Marx

《It is only concerned with demand that is backed by ability to pay. It is not a question of absolute over-production—over-production as such in relation to the absolute need or the desire to possess commodities. In this sense there is neither partial nor general over-production; and the one is not opposed to the other.》

ch.17

[9. Ricardo’s Wrong Conception of the Relation Between Production and Consumption under the Conditions of Capitalism]

tr:《…それは支払能力に支えられた需要にのみ関係しています。 絶対的な過剰生産、つまり絶対的な必要性や商品を所有したいという願望に関連した過剰生産の問題ではありません。 この意味で、部分的または一般的な過剰生産はありません。 そして一方は他方に反対していない。》

剰余価値学説史 Theorien über den Mehrwert 1963

[#11:178]

12 Mr. Keynes and the ‘Classics’ 180

12.1 Introduction 180

12.2 The Existence of Mass Unemployment as an Equilibrium Phenomenon 181

12.3 Keynes’ Critique of Classical Employment Theory 182

12.4 Involuntary Unemployment 186

12.5 Keynes’ Rejection of Say’s Law: The Possibility of General Overproduction 188

Refresher: the loanable funds market 188

Keynes’ critique of the loanable funds doctrine 188

Liquidity preference and Keynes’ theory of interest 190

Conclusion 192

References 192

^

12ケインズ氏と「古典」180

12.1はじめに180

12.2均衡現象としての大量失業の存在181

12.3ケインズの古典的雇用理論の批判182

12.4不本意失業186

12.5ケインズのセイの法則の拒絶:一般的な過剰生産の可能性188

更新者:ローンファンド市場188

ケインズのローン可能資金の教義に対する批判188

流動性の選好とケインズの利子理論190

結論192

参照192

参考:

The natural rate of interest is zero! billSunday, August 30, 2009

13 The Theory of Effective Demand 193

13.1 Introduction 193

13.2 The D-Z Approach to Effective Demand 194

13.3 Introducing Two Components of Aggregate Demand: D1 and D2 198

13.4 Advantages of the D-Z Framework 199

The macroeconomic demand for labour 199

13.5 The Role of Saving and Liquidity Preference 200

13.6 The Demand Gap Arguments and Policy Implications 201

Conclusion 202

Reference 203

^

13実効需要理論193

13.1はじめに193

13.2有効需要へのD-Zアプローチ194

13.3総需要の2つの要素の紹介:D1とD2 198

13.4 D-Zフレームワークの利点199

労働に対するマクロ経済的需要199

13.5貯蓄と流動性嗜好の役割200

13.6需要ギャップの議論と政策への影響201

結論202

参考資料203

14 The Macroeconomic Demand for Labour 204

14.1 Introduction 204

14.2 The Macroeconomic Demand for Labour Curve 205

The interdependency of aggregate supply and demand 205

Money wage changes and shifts in effective demand 206

14.3 The Determination of Employment and the Existence of Involuntary Unemployment 211

14.4 A Classical Resurgence Thwarted 213

Conclusion 214

References 215

^

14労働に対するマクロ経済的需要204

14.1はじめに204

14.2労働曲線205のためのマクロ経済的な要求

総需給の相互依存関係205

貨幣賃金の変化と実効需要の推移206

14.3雇用の決定および非自発的失業の存在211

14.4 213を阻止した古典的な復活

結論214

参考文献215

#14:209 Keynes and the Classics Part 8 – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

#14:215^211

[REFERENCE: Pigou, A. (1943) The Classical Stationary State, The Economic Journal, December, LIII, 343-51 – link is to JSTOR if your library has a subscription] NOTE:

The Keynes and Classics series so far is:

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 1 – explains how the Classical system conceived of labour supply and demand and how these come together to define the equilibrium level of the real wage and employment.[#11:166,167]

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 2 – explains how the labour market determines the level of employment and real wage, which in turn, via the production function set the real level of output.[#11169,171,173]

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 3 – tied the previous conceptual development into the denial that there could be aggregate demand failures (Say’s Law), introduced the loanable funds market and discussed the pre-Keynesian critique (Marx) of the Classical full employment model.[#11:173,174]

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 4 – which began Keynes’ critique of Classical employment theory.

- Keynes and the Classics – Part 5 – continues the critique of Classical employment theory.[#15:187]

- Keynes and the Classics Part 6 – considers Keynes’ critique of the Classical Theory of Interest.[#12:189]

- Keynes and the Classics Part 7 – introduces the preliminary concepts in developing a macroeconomic theory of labour demand.

- Keynes and the Classics Part 8 – developed the three cases underpinning the possible shape of a macroeconomic theory of labour demand.[#13:197?,#14:207,208,209]

- Keynes and the Classics Part 9 - [#14:210,212] :頁数は図

#14:209~214 Keynes and the Classics Part 8,9 – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

(ピグー効果、後述の100匹の犬と骨の話213も)

#14:211 ピグー、ワイントローブ

ピグー効果

ピグー効果(ピグーこうか、英: Pigou effect)とは、特にデフレーションにおいて、資産(wealth)の実質価値の増加が生産高や雇用に刺激を与える効果のことである[1]。「資産効果」と呼ばれることもある[2][3]。 …

解説

物価と貨幣賃金が十分に下落すれば、消費者が保有している資産の実質的な価値が上がることにより、消費が増大(IS-LMモデルで言えば、IS曲線が右にシフト)し、雇用と生産が増え、完全雇用が達成される[4]とアーサー・セシル・ピグーは考えた。すなわち、ピグー効果を前提に考えると、仮に経済が不景気に陥り、失業(貨幣賃金の低下)が発生すると、デフレ状態になり、ピグー効果によって消費の増大(需要の増大)が起こり、そして雇用の増大がなされ、経済は自動的に(自己修正的に)景気回復へ向かうだろうということが言える。このピグー効果という用語は新古典派経済学者であるアーサー・セシル・ピグーの名前をとってドン・パティンキンが1948年に使いはじめた[5][6][7]。 しかしながら、G.バーバラーやT.シトフスキーはピグー以前にも同じ所得効果を指摘しており、現在では実質残高効果や資産効果と呼ぶことも多い[8]。ピグー効果が示された論文として有名なのは1943年のピグーの論文「The Classical Stationary State」である。なお、ピグーは新古典派の経済学者であることに留意する必要がある。 ここで、資産(wealth)とは、ピグーによって、マネーサプライと国債の和を物価で割ったものと定義されている[1]。ピグーは、賃金引下げによって物価(生産物の貨幣価格)が下がることによって、資産の実質価値が大きくなり、その実質購買力の増加が生ずるので、これが支出(特に消費支出)を刺激し、雇用が拡大すると論じた[9]。これがピグ―効果である。 彼は次の点が明記されていないジョン・メイナード・ケインズの『一般理論』は不十分であると論じた。すなわち、実質残高と現在の消費のつながりと、このような富効果が総需要の落ち込みに対して、ケインズが予測したよりも経済をより「自己修正的」にするだろうという点である[1]。 この「貨幣賃金を引き下げることによって雇用が増大する」というピグーのアイデアに対しては、「不況や失業を克服するためには政府が積極的に介入するべき」という立場を取るケインジアン達から批判がなされた。…

Major works of Sidney Weintraub ... "A Macroeconomic Approach to the Theory of Wages", 1956, AER.

シドニー・ワイントラウプ(Sidney Weintraub、1914~1983)

参考:

MMT predicts well – Groupthink in action 2017 bill

#14:214

アクセル・レイヨンフーヴッド (Axel Leijonhufvud), 1933-

#14:209 Keynes and the Classics Part 8 – Bill Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory

Clower,R(1965)

R・W・クラウアー

ケインジアンの反革命:理論的評価

邦訳『ケインズ経済学の再評価』1980所収

part9:tr:

Clower(1965)は、労働市場における過剰供給(失業)が経済の他の場所、特に製品市場において過剰需要を通常伴わないことを示した。過剰な要求は金銭的に表現されます。どのようにして失業者(概念的または潜在的な製品要求があったか)が雇用主(製品市場の売り手)に彼らの要求意図を知らせることができるでしょうか。

Leijonhufvud(1968)は、不均衡では、価格調整は数量調整に比べて遅いという考えを追加しました。 Leijonhufvudは、ケインズの均衡の概念を、実際には永続的な不均衡であるとよりよく考えられていると解釈しました。したがって、失業者は、雇用されればもっと多くの財やサービスを買うと合図することができないため、不本意な失業が起こります。

15 The Aggregate Expenditure Model 216

15.1 Introduction 216

15.2 A Simple Aggregate Supply Depiction 217

15.3 Aggregate Demand 218

15.4 Private Consumption Expenditure 219

15.5 Private Investment 222

15.6 Government Spending 224

15.7 Net Exports 224

15.8 Total Aggregate Expenditure 225

15.9 Equilibrium National Income 228

15.10 The Expenditure Multiplier 230

An algebraic treatment 231

A graphical treatment 232

Numerical example of the expenditure multiplier at work 234

Changes in the magnitude of the expenditure multiplier 235

A final point about the multiplier 236

Conclusion 238

References 238

^

15総支出モデル216

15.1はじめに216

15.2単純な総計供給図217

15.3総計要求218

15.4個人消費支出219

15.5民間投資222

15.6政府支出224

15.7純輸出224

15.8総計支出225

15.9均衡国民所得228

15.10経費乗数230

代数的取扱い231

グラフィカルな治療232

職場での支出倍率の数値例234

支出乗数235の大きさの変化

乗数236についての最後のポイント

結論238

参考文献238

#15:218

45度線分析

(15.7:231)

乗数プロセス:(後述)

┏━━━━━┓ ┏━━━━┓

支出変化➡︎┃総需要拡大┃➡︎実質GDP上昇➡︎┃雇用拡大┃

┗━━━━━┛ ┗━━━━┛

誘発的消費拡大 ↖︎ ┏━━━━━━┓ ↙︎賃金他支払い

┃国民所得拡大┃

┗━━━━━━┛

⬇︎

税収、貯蓄、輸入増加

#15

the Aggregate Demand Function

15.8 Impact of a change in government spending on equilibrium expenditure and income 233

15.8 Impact of a change in government spending on equilibrium expenditure and income 233

…

Figure 8.11 The multiplier flow map

:書籍版未採用

16 Aggregate Supply 239

16.1 Introduction 239

16.2 Some Important Concepts 240

Schedules and functions 240

The employment-output function 240

Money wages 242

16.3 Price Determination 244

16.4 The Aggregate Supply Function (AS) 245

The theory of production 247

Some properties of the aggregate supply function 248

16.5 What Determines the Level of Employment? 249

16.6 Factors Affecting Aggregate Output per Hour 249

The choice of production technology 250

Procyclical movements in labour productivity 251

Conclusion 252

Reference 252

^

16総計供給239

16.1はじめに239

16.2いくつかの重要な概念240

スケジュールと機能240

雇用産出機能240

マネー賃金242

16.3価格決定244

16.4集約供給機能(AS)245

生産論247

集合供給関数248のいくつかの特性

16.5何が雇用レベルを決定する? 249

16.6 1時間あたりの集計出力に影響を与える要因249

生産技術の選択250

労働生産性における巡回運動251

結論252

参考資料252

#16:242

#16:247

#16 When the MMT critics jump the shark – Bill Mitchell [General Aggregate Supply Function]

図C:

11.1 The Classical production function 166

11.2 The Classical labour market equilibrium 167

11.3 Unemployment in the Classical labour market 169

11.4 Classical equilibrium output determination 171

11.5 Classical interest rate determination 173

11.6 Increased desire for consumption 174

^

11.1クラシックプロダクション機能166

11.2古典的な労働市場の均衡167

11.3古典労働市場における失業率169

11.4古典的均衡生産量の決定171

11.5古典的な金利の決定173

11.6消費に対する欲求の増大174

12.1 Keynesian aggregate labour supply function 187

12.2 The interdependence of saving and investment 189

^

12.1ケインジアン総労働供給機能187

12.2貯蓄と投資の相互依存性189

13.1 Keynes’ D-Z aggregate framework 197

^

13.1ケインズのD-Z集約フレームワーク197

14.1 The ‘Classical’ case 207

14.2 The ‘Keynesian’ case 208

14.3 The ‘underconsumptionist’ case 209

14.4 A generalised macroeconomic demand curve for labour 210

14.5 Employment and unemployment 212

^

14.1「古典的」な場合207

14.2「ケインジアン」事件208

14.3「過少消費者」事件209

14.4労働の一般化されたマクロ経済需要曲線210

14.5雇用と失業212

15.1 Aggregate supply 218

15.2 The consumption function 222

15.3 The aggregate demand function 226

15.4 Increase in the intercept of the aggregate demand function with increased autonomous spending 227

15.5 Changing slope of the aggregate demand function with increased marginal propensity to consume 228

15.6 Planned expenditure and equilibrium income 229

15.7 The multiplier process 231

15.8 Impact of a change in government spending on equilibrium expenditure and income 233

15.9 Impact of a change in the marginal propensity to consume on equilibrium expenditure and income 236

^

15.1総計供給量218

15.2消費機能222

15.3総需要関数226

15.4自律支出の増加に伴う総需要関数の切片の増加227

15.5限界消費性向の増加に伴う総需要関数の傾きの変化228

15.6計画支出と均衡収入229

15.7乗数プロセス231

15.8政府支出の変動が均衡支出と所得に与える影響233

15.9限界消費性向の変化が均衡支出と所得に与える影響236

16.1 The employment-output function 242

16.2 Output, sales and national income 246

16.3 The general aggregate supply function (AS) 247

16.4 US manufacturing output per person employed 1987 to 2017 250 ^

16.1雇用産出機能242

16.2生産高、売上高および国民所得246

16.3一般的な総合供給機能(AS)247

16.4 1人当たりの米国の製造業生産高1987年から2017年250

表C:

15.1 Consumption ratios, OECD nations, 2010 and 2016, per cent 220

15.2 Expenditure chain volume measures in national accounts (seasonally adjusted), Australia, 2017 223 15.3 The expenditure multiplier process 234

15.4 Simulating changes in the multiplier components 237

^

15.1消費率、OECD諸国、2010年および2016年、220パーセント

15.2国民経済計算における支出連鎖量の指標(季節調整済み)、2017年、オーストラリア

15.3支出倍率プロセス234

15.4乗数コンポーネントの変化のシミュレーション237

箱C:

12.1 Is there an inverse relation between employment and real wages? A critique of the First Postulate 185

12.2 Graphical exposition showing saving and investment are not independent 189

14.1 The Tale of 100 Dogs and 95 Bones 213

15.1 Inventory movements and planned investment 230

16.1 The Perils of Neglecting Innovation 241

^

12.1雇用と実質賃金の間に逆の関係がありますか?第一仮説185に対する批判

12.2貯蓄と投資が独立していないことを示すグラフィカルな説明

14.1犬100匹と骨95匹の物語213

15.1在庫移動と計画投資230

16.1イノベーション無視の危険性241

PART D: UNEMPLOYMENT AND INFLATION: THEORY AND POLICY [#17~19] (17 Unemployment and Inflation

18 The Phillips Curve and Beyond

19 Full Employment Policy)

^

パートD:未採用とインフレーション:理論と政策[#17〜19]

(17失業率とインフレ

18フィリップス曲線とその先

19完全雇用政策)

We highlight the deficiencies of the Quantity Theory of Money (Chapter 17). In Chapter 18 the early Phillips Curve debate is outlined, and this is followed by a criti-cal analysis of the expectations augmented Phillips Curve which continues to have a profound infl uence on the conduct of macroeconomic policy in developed economies more than 40 years later. Students are also exposed to recent advances in the Phillips curve literature which include hysteresis and hence the importance of the duration of unemployment, and also the role of underemployment. Most policymakers continue to utilise a buffer stock of unemployment to counter inflationary pressure. Chapter 19 explores the merits of a Job Guarantee which is based on an employment buff er stock and is designed to achieve both full employment and price stability in concert with other macroeconomic policies.