Money and Banking – Part 1: Balance Sheet

By Eric Tymoigne

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2016/01/money-banking-part-1.html

お金と銀行業務 - パート1:バランスシート

投稿日:2016年1月9日、Eric Tymoigne

Eric Tymoigne著

私はM&Bコースを一緒にするために数年間苦労しました。それは一貫性に欠けていたし、学生はコースのさまざまな部分をリンクすることが困難でした。問題の大部分は、M&Bの教科書から来ています。これは、古くなったプレゼンテーションの他に、一貫したコアのない、さまざまな章の集まりです。それで私は教科書をあきらめて私自身のやり方で進み、そして私の学生の間で理解は劇的に増加しました。

金融システムの中核は財務書類で構成され、その中には貸借対照表があります。バランスシートはM&Bコースの大部分を教えることができる基礎を提供します:銀行と中央銀行による貨幣創造、お金の性質、金融危機、証券化、金融相互依存、あなたがそれを言う、それは1つまたはいくつかのバランスと関係がありますシート)。 Hyman P. Minskyが以前に注意したように、あなたがバランスシートに関してあなたの推論を置くことができないならば、あなたの論理に問題があります。

だから私のM&Bの「教科書」の第1章はバランスシートの仕組みについてです。はい、会計は面倒ですが、金融の仕組みを理解するためには、主要な会計の概念をよく理解しておく必要があります。通常、M&Bのテキストの最初にある「お金」の章は、バランスシートの仕組みと現在価値などの財務の概念がよく理解されてから初めて登場します。これは私がM&Bですることすべてを網羅するものではありません。私は、銀行、中央銀行、金融システムに関連するマクロ経済の話題、そしてお金に焦点を当てます。

貸借対照表とは何ですか?

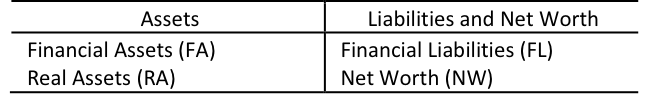

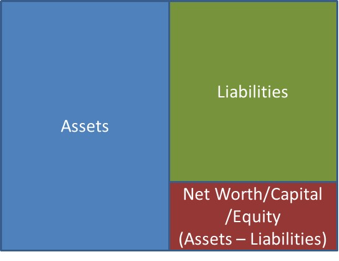

それは、経済単位が所有しているもの(「資産」)および所有しているもの(「負債」)を記録する会計文書です。資産と負債の違いは、純資産、資本、または資本と呼ばれます。

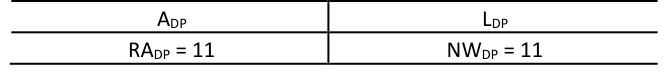

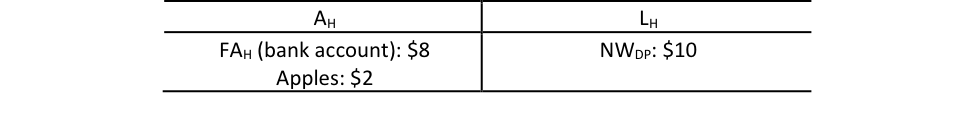

図0a貸借対照表

図0a貸借対照表

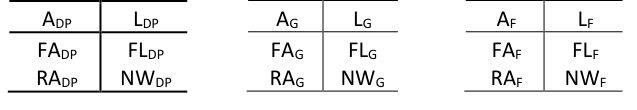

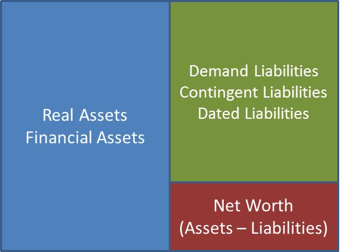

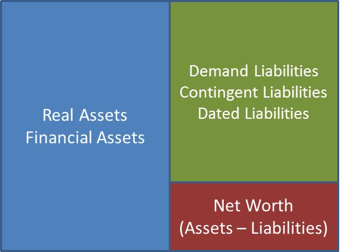

資産と負債を分類するにはさまざまな方法があります。私たちの目的のために、貸借対照表は以下のようにもう少し詳細にすることができます。

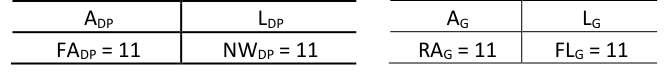

図0b簡単な貸借対照表

図0b簡単な貸借対照表

金融資産は他の経済単位に対する債権であり、実物資産は物理的なもの(自動車、建物、機械、ペン、机、在庫など)に減らすことができますが、無形のもの(例えば、営業権)も含むことができます。デマンド負債は、債権者の要求により支払われるべき負債(例、口座保有者が現金を銀行口座から自由に引き出すことができる)であり、偶発債務は、特定の事由が発生した時(例、未亡人への生命保険支払い)負債は特定の期間に支払われる(例えば、利息および元本抵当支払は毎月支払期日が到来する)。

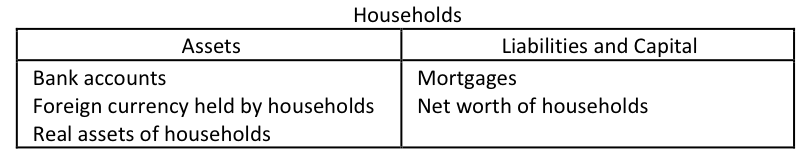

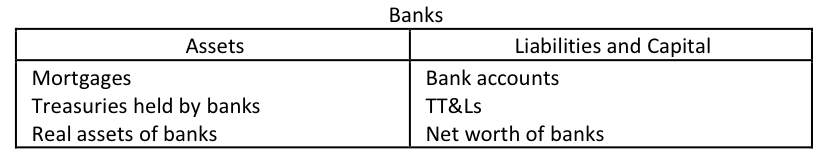

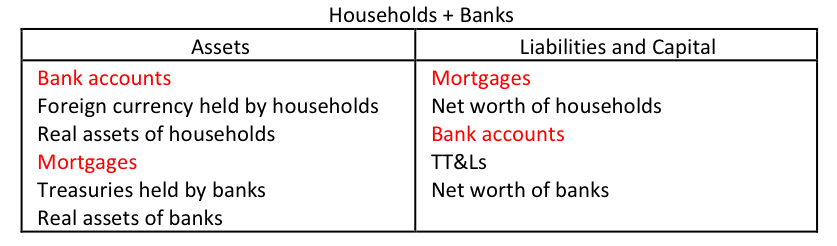

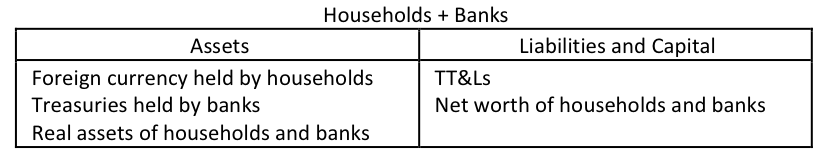

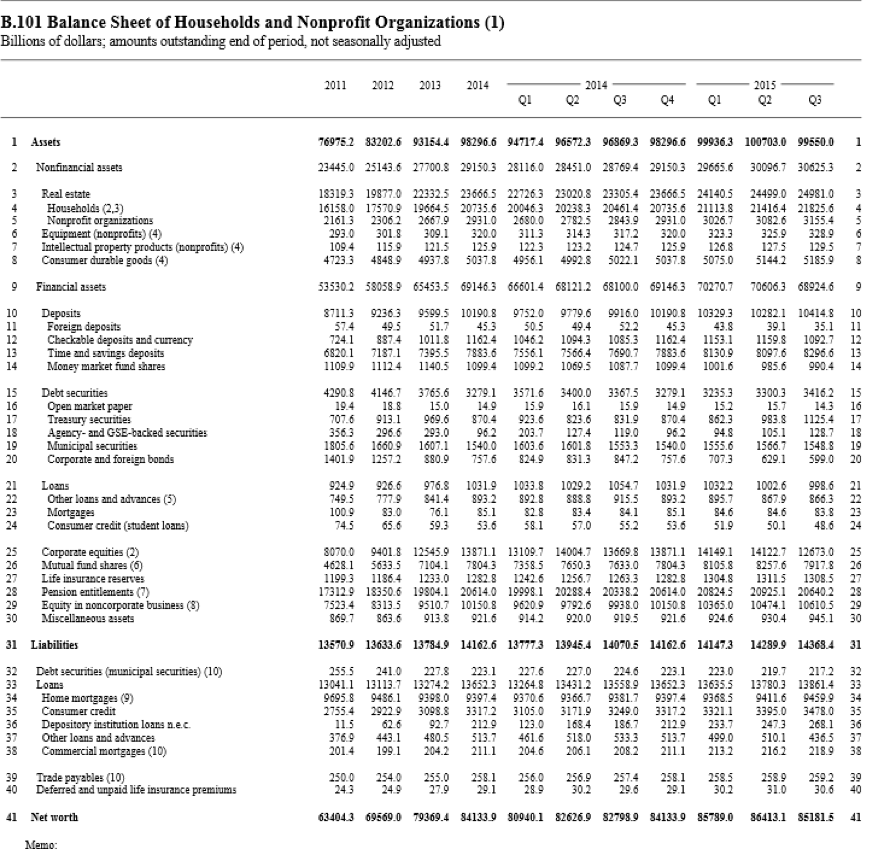

貸借対照表は、あらゆる経済単位に対して構成することができます。その単位は、人、会社、経済部門、国、誰でも、あるいは資産と負債を持つものでもよい。表1は、米国内の米国の世帯(および非営利団体)の貸借対照表です。 2015年第3四半期、米国の世帯は99.6兆ドル相当の資産を所有し、14.4兆ドル相当の負債を負っており、純資産は85.2兆ドル(99.6 - 14.4)に相当します。世帯は30.6兆ドルの実資産、68.9兆ドルの金融資産を保有していました。彼らの2つの主な負債は、住宅ローン(9.5兆ドル)と消費者信用、すなわちクレジットカード、学生の借金など(3.5兆ドル)でした。

fig0-c

表1世帯とNPOのバランスシート

出典:米国の金融口座

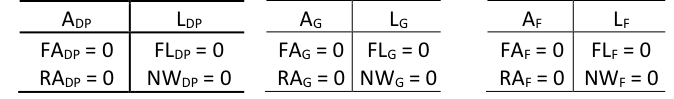

貸借対照表のルール

貸借対照表は複式会計規則に従っているので、貸借対照表は常に貸借対照表でなければなりません。つまり、次のことが常に当てはまる必要があります。

資産=負債+純資産

実用的かつ中心的な意味は、貸借対照表上の1つの項目の変更は、貸借対照表が均衡を保つように他の場所で少なくとも1つの変更によって相殺されなければならないということです。

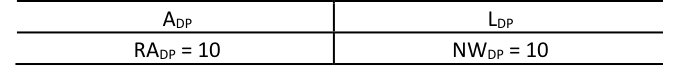

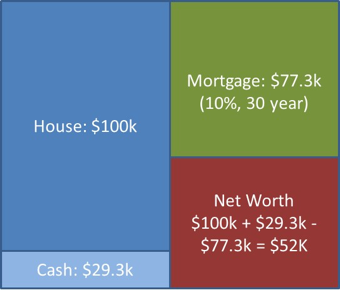

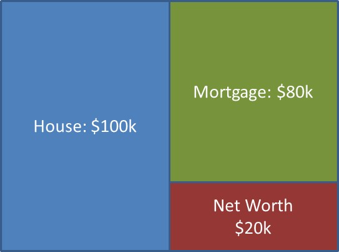

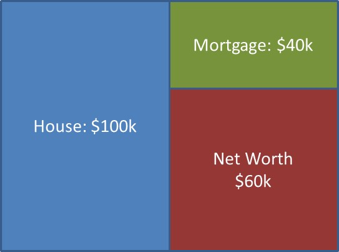

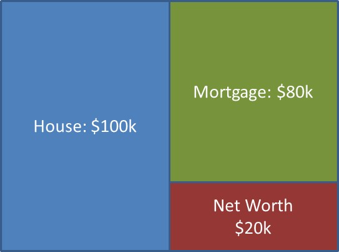

非常に単純なバランスシートから始めましょう。唯一の資産は、20,000ドルを預けて銀行から8万ドルを要求することによって購入された1万ドル相当の家です。

図1.単純なバランスシート

図1.単純なバランスシート

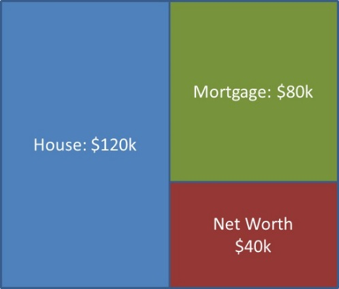

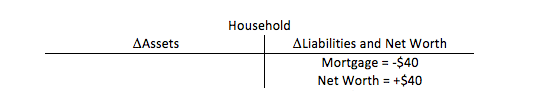

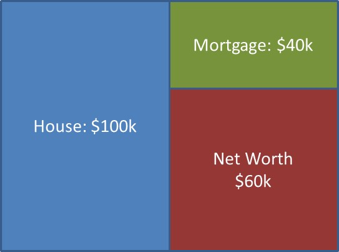

銀行が4万ドルの元本(すなわち、未払残高)を許すことが住宅ローンに与える影響は何ですか?

図2住宅ローン元本返済の影響

図2住宅ローン元本返済の影響

住宅ローンの価値は40k減少し、自己資本の価値は40k増加したため、会計上の平等性は維持されます。

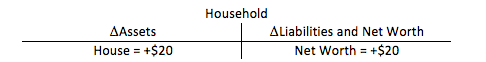

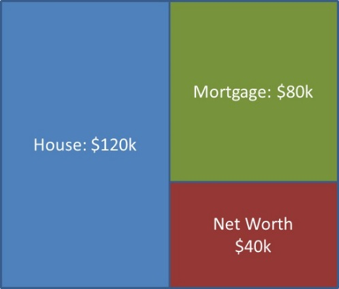

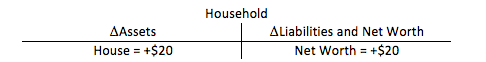

最初の貸借対照表に戻って、家の価値が2万ドル上昇したことによる影響は何ですか?

図3住宅価格の上昇による影響

図3住宅価格の上昇による影響

資産価値は20,000ドル上昇し、純資産は20ドル上昇しました。ここでも、会計の平等性は維持されます。

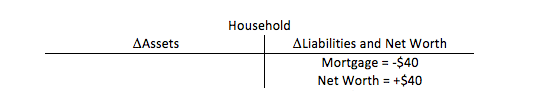

経済学者は、ポイントをもっと早く見つけて変更を強調するために、バランスシートの変更のみを記録する、いわゆる「T勘定」を使用することを好むことがあります(テーブルの形状はTのように見えるため)。

図4. thを記録するTアカウント

住宅ローン元本の返済

図4.住宅ローン元本の返済を記録するT勘定

図5.高い家の価値を記録するTアカウント

図5.高い家の価値を記録するTアカウント

オフセットがより明確に示されています。これは、貸借対照表の右側にある2つの項目の反対の変動(図4)と、資産と純資産の同額の変動(図5)から生じます。もちろん、会計上の平等を維持するために相殺が行われる2つの方法はこれらだけではありません。前進するにつれて、他の事件に遭遇するでしょう。重要なのは、平等A = L + NWが確実に維持されるように、バランスシートの少なくとも2つを変更しなければならないということです。常に尋ねなければなりません:相殺されるエントリーの変更は何ですか?これは、銀行と中央銀行がどのように機能するのかを研究する上で実際的な意味を持ちます。

バランスシートは何が変わりますか?

貸借対照表を変更する要因を3つのカテゴリに分類することができます。

キャッシュインフローとアウトフロー:純キャッシュフロー

収入および費用:純利益

キャピタルゲインおよびキャピタルロス:資産および負債の市場価値の純変動

これらのカテゴリは、貸借対照表よりも他の会計伝票に慎重に記録されていますが、このセクションでは、貸借対照表との関係に焦点を当てます。

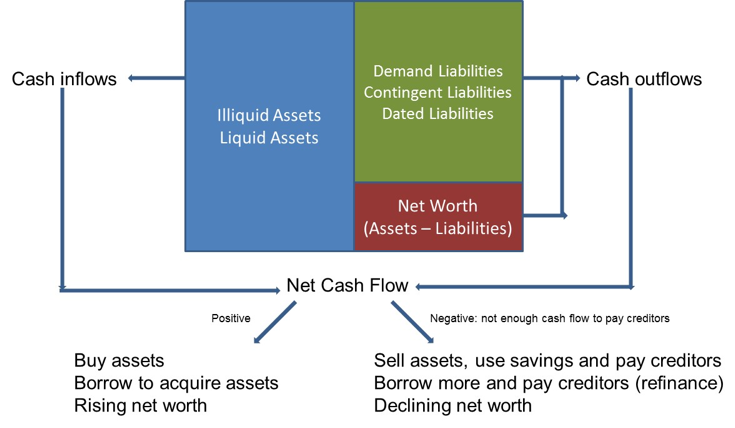

ネットキャッシュフロー

キャッシュインフローおよびキャッシュアウトフローは、経済的単位によって保有されている通貨残高の量の変化、すなわち資産側で保有されている銀行口座の物理通貨または資金の量の変化につながる。一部の資産は現金の流入につながり、一部の負債および資本(配当金の支払い)は現金の流出につながります。

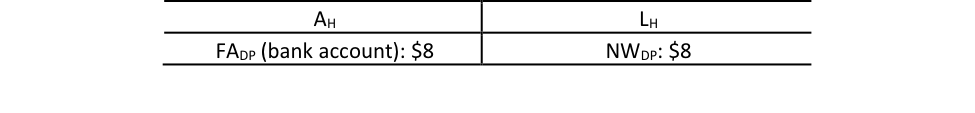

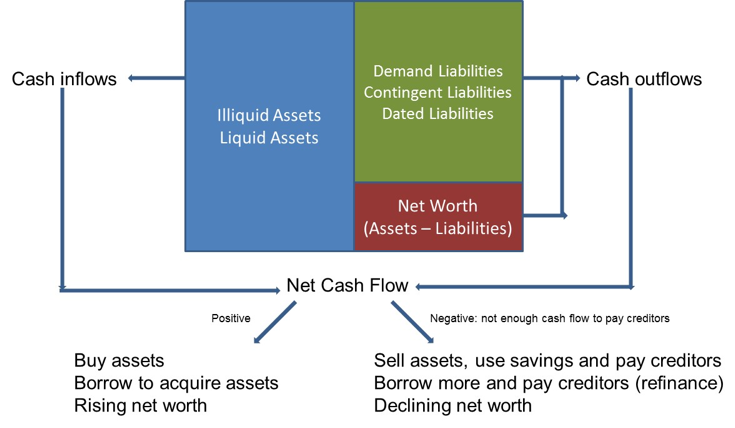

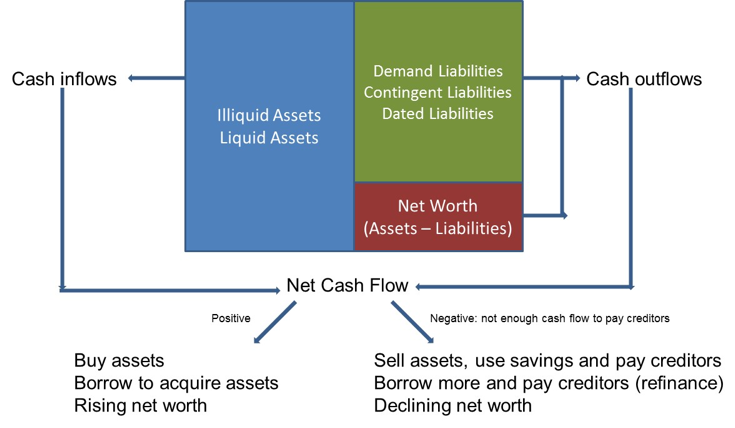

図6.貸借対照表とキャッシュフロー

図6.貸借対照表とキャッシュフロー

Figure 6. Balance sheet and cash flow

If the cash inflows are greater than the cash outflows, monetary assets held by an economic unit go up. The economic unit can use them to buy assets or pledge them to leverage its balance sheet (see Post 7). If net cash flow is negative, then monetary-asset holdings fall and the economic unit may have to go further into debt to pay some of its expenses.

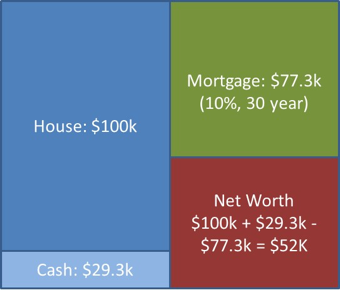

Going back to our very simple balance sheet, assume that a salary of $40k is earned and that part of the salary is used to service a 30-year fixed-rate 10 % mortgage. Assuming linear repayment of principal to simplify (actual mortgage servicing is calculated differently), the cash flow structure looks like this:

Figure 7. Balance sheet and cash flows, an example

The balance sheet at the beginning of the following year is (assuming all cash flows involve actual cash transfer instead of electronic payments):

キャッシュインフローがキャッシュアウトフローよりも大きい場合、経済単位によって保有されている貨幣資産は上がります。経済単位はそれらを使って資産を購入したり、バランスシートを活用することを約束したりすることができます(ポスト7参照)。正味キャッシュフローがマイナスであれば、貨幣性資産の保有量は減少し、経費の一部を支払うために経済単位がさらに借金をしなければならなくなる可能性があります。

非常に単純なバランスシートに戻って、40,000ドルの給与が稼得され、その給与の一部が30年固定金利の10%住宅ローンの返済に使用されると仮定します。単純化する元本の線形返済を仮定すると(実際の住宅ローン返済は異なる方法で計算されます)、キャッシュフロー構造は次のようになります。

図7.貸借対照表とキャッシュフロー、一例

図7.貸借対照表とキャッシュフロー、一例

翌年の初めの貸借対照表は次のとおりです(すべてのキャッシュフローに電子決済の代わりに実際の現金振替が含まれると仮定して)。

図8.キャッシュフロー影響後の貸借対照表

図8.キャッシュフロー影響後の貸借対照表

バランスシートには、かなりの変化があります。現金の純流入額は29.3万ドルで、住宅ローンの元本は元本の返済額分減少し、純資産はこれら2つの変更を反映しています。

当期純利益

純利益は純資産の変化につながります。

当期純資産=以前の純資産+当期純利益

純利益(例えば、税引前利益が純利益の代用であること)は、正または負になることがあり、したがって純資産は増減することがある。前の例(図7と8)では、純キャッシュフローと純利益は同じものです。しかし、すべての収入が必ずしも現金の流入につながるわけではありません(ポスト4、10を参照)。

キャピタルゲインとキャピタルロス

最後に、資産および負債の価値は、それらの市場価値の変動により変動する可能性があります。会計処理が「時価評価」ベースで行われる場合、すなわち現在の市場価値に基づいて貸借対照表項目を評価することによって行われる場合、これらの変更は貸借対照表に計上され、それに応じて純資産が影響を受けます。

現在の純価値=前の純価値+当期純利益+当期純キャピタルゲイン

図3の例は、キャピタルゲインの影響を簡単に示しています。

資産および負債の時価の変動による影響は、それらが原価ベースで評価される場合には貸借対照表に計上されない可能性がある。金融資産については、その価値を記録するための3つの選択肢があります。レベル1の評価は利用可能な市場価格を使用します。活発な市場がない資産のレベル2評価では、参照市場として代理市場が使用されます。 Mark-to-Model(またはより皮肉な「Mark-to-Myth」)とも呼ばれるレベル3の評価では、資産にドルの値を与えるために社内モデルを使用します。 2008年の危機の間、主要な金融機関は一部の資産の市場価格は市場のパニックのためにそれらの真の価値を反映していないと主張しました。証券取引委員会は、資産の価値を維持するために、レベル2またはレベル3の評価に移行することを許可しました。多くのアナリストがこの決定に批判的であり、それが機関の大きな損失を隠すための便利な方法であると考えました。

それは今日のそれです!以下の投稿では、これらすべてを銀行および中央銀行に適用します。

[2016年7月21日改訂]

I struggled a few years to get an M&B course together. It lacked coherency and students had difficulty to link the different parts of the course. A good part of the problem comes from the M&B textbooks that, besides having outdated presentations, are a disparate collection of chapters without a coherent core. So I gave up with textbooks and went my own way, and comprehension dramatically increased among my students.

The core of the financial system consists of financial documents and among them are balance sheets. Balance sheets provide the foundation upon which most of an M&B course can be taught: monetary creation by banks and the central bank, nature of money, financial crises, securitization, financial interdependencies, you name it, it has to do with one or several balance sheet(s). As Hyman P. Minsky used to note, if you cannot put your reasoning in terms of a balance sheet there is a problem in your logic.

So chapter 1 in my M&B “textbook” is about balance-sheet mechanics. Yes accounting is tedious, but one must get a good grasp of key accounting concepts to understand financial mechanics. The “money” chapter, usually first in M&B texts, only comes much later once balance-sheet mechanics and financial concepts such as present value have been well understood. This will not cover everything I do in M&B. I will focus on banks, central bank, macroeconomic topics related to the financial system, and money.

What is a balance sheet?

It is an accounting document that records what an economic unit owns (its “assets”) and owes (its “liabilities”). The difference between its assets and liabilities is called net worth, or equity, or capital.

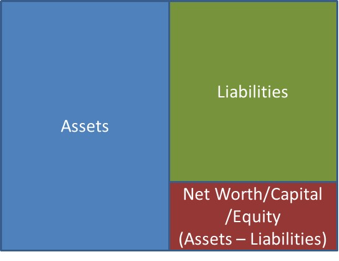

Figure 0a. A balance sheet

There are many different ways to classify assets and liabilities. For our purpose, a balance sheet can be detailed a bit more as follows:

Figure 0b. A simple balance sheet

Financial assets are claims on other economic units and real assets may be reduced to physical things (cars, buildings, machines, pens, desks, inventories, etc.) but may also include intangible things (e.g., goodwill). Demand liabilities are liabilities that are due at the request of creditors (e.g., cash can be withdrawn from bank accounts at will by account holders), contingent liabilities are due when a specific event occurs (e.g., life insurance payments to a widow), dated liabilities are due at specific periods of time (e.g., interest and principal mortgage payments are due every month).

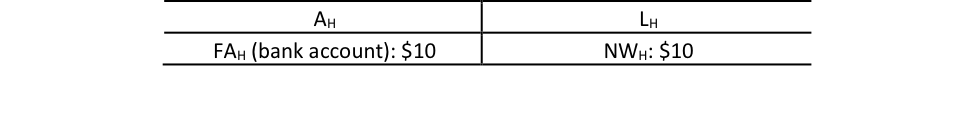

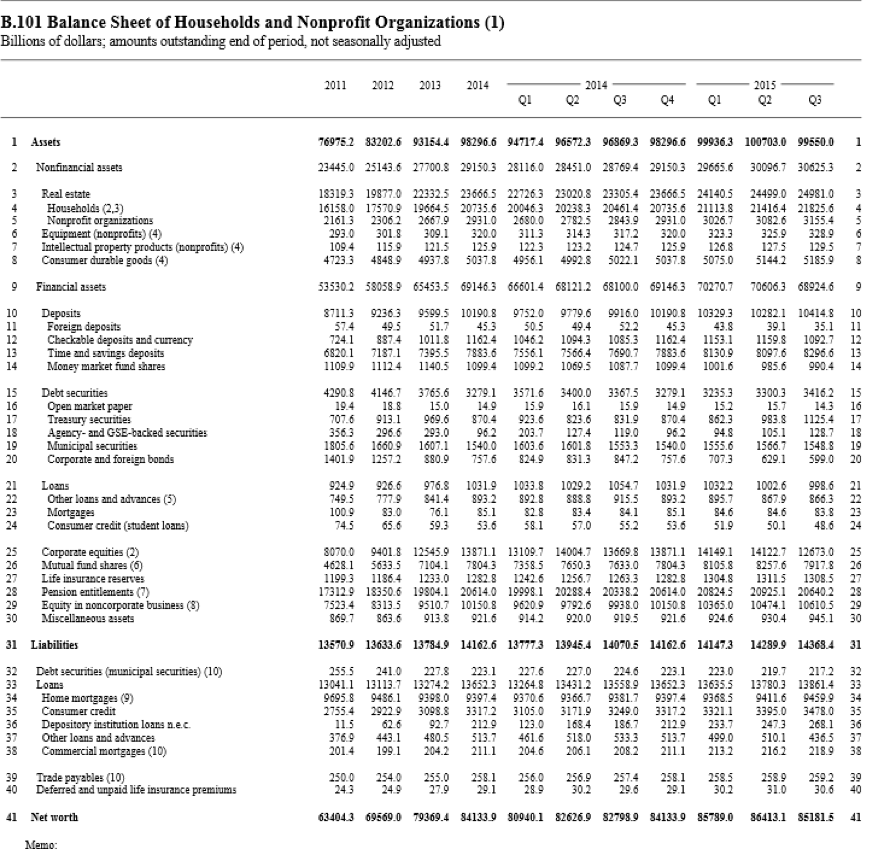

Balance sheets can be constructed for any economic unit. That unit can be a person, a firm, a sector of the economy, a country, anybody or anything with assets and liabilities. Table 1 is the balance sheet of U.S. households (and non-profit organizations) in the United States. In the third quarter of 2015, U.S. households owned $99.6 trillion worth of assets and owed $14.4 trillion worth of liabilities, making net worth equal to $85.2 trillion (99.6 – 14.4). Households held $30.6 trillion of real assets, $68.9 trillion of financial assets. Their two main liabilities were home mortgages ($9.5 trillion) and consumer credit, i.e. credit cards, student debts, etc. ($3.5 trillion).

Table 1. Balance sheet of households and NPOs.

Source: Financial Accounts of the United States

Balance sheet rules

A balance sheet follows double-entry accounting rules so A BALANCE SHEET MUST ALWAYS BALANCE, that is, the following must always be true:

Assets = Liabilities + Net Worth

The practical, and central, implication is that a change in one item on the balance sheet must be offset by at least one change somewhere else so that a balance sheet stays balanced.

Let’s start with a very simple balance sheet. The only asset is a house worth $100k that was purchased by putting down 20k and asking for $80k from a bank:

Figure 1. A simple balance sheet

What is the impact of a bank forgiving $40k of principal (i.e. outstanding amount owed) on the mortgage?

Figure 2. Effect of Repayment of Mortgage Principal

The value of mortgage went down by 40k and the value of net worth went up by 40k so that the accounting equality is preserved.

Going back to the first balance sheet, what is the impact of the value of the house going up by $20k?

Figure 3. Effect of higher house price

The asset value went up by $20k and the net worth went up by $20 and here again the accounting equality is preserved.

Sometimes, to get to the point more quickly and to highlight the changes, economists prefer to use so-called “T-accounts” (because the shape of the table looks like a T) that record only the changes in the balance sheet.

Figure 4. T-account that records the repayment of the mortgage principal

Figure 5. T-account that records the higher house value

The offsetting is shown more clearly. It comes from opposite changes in two items on the right side of the balance sheet (Figure 4), and a change in asset and net worth by the same amount (Figure 5). Of course these are not the only two ways the offsetting is done to preserve the accounting equality. We will encounter other cases as we move forward. The point is that one must change at least two things in a balance sheet to make sure that the equality A = L + NW is preserved. One must always ask: what is the offsetting entry change? This has practical implications when studying how banks and central bank operate.

What makes the balance sheet change?

One can classify factors that change a balance sheet in three categories:

- Cash inflows and outflows: net cash flow

- Incomes and expenses: net income

- Capital gains and capital losses: net change in the market value of assets and liabilities

These categories are recorded more carefully in other accounting documents than the balance sheet, but this section focuses on their relation to the balance sheet.

Net Cash Flow

Cash inflows and cash outflows lead to a change in the amount of monetary balances held by an economic unit, i.e. a change in the amount of physical currency or funds in a bank account held on the asset side. Some assets lead to cash inflows while some liabilities and capital (dividend payments) lead to cash outflows.

Figure 6. Balance sheet and cash flow

If the cash inflows are greater than the cash outflows, monetary assets held by an economic unit go up. The economic unit can use them to buy assets or pledge them to leverage its balance sheet (see Post 7). If net cash flow is negative, then monetary-asset holdings fall and the economic unit may have to go further into debt to pay some of its expenses.

Going back to our very simple balance sheet, assume that a salary of $40k is earned and that part of the salary is used to service a 30-year fixed-rate 10 % mortgage. Assuming linear repayment of principal to simplify (actual mortgage servicing is calculated differently), the cash flow structure looks like this:

Figure 7. Balance sheet and cash flows, an example

The balance sheet at the beginning of the following year is (assuming all cash flows involve actual cash transfer instead of electronic payments):

Figure 8. Balance sheet after the cash-flow impacts

Quite a few things have change in the balance sheet. There is a net inflow of cash of $29.3k, the principal of the mortgage fell by the amount of principal repaid, and net worth accounts for these two changes.

Net Income

Net income leads to a change in the net worth:

Current Net worth = Previous Net worth + Net income of the period

Net income (e.g., earnings before taxes is a proxy of net income) can be positive or negative so net worth may rise or fall. In the previous example (Figures 7 and 8), net cash flow and net income are the same thing; however, not all incomes necessarily lead to cash inflows (see Post 4, and 10).

Capital Gains and Capital Losses

Finally, the value of assets and liabilities may change because of changes in their market value. If accounting is done on a “mark-to-market” basis, i.e. by valuating balance-sheet items based on their current market value, these changes will be accounted in the balance sheet and net worth will be affected accordingly:

Current Net Worth = Previous Net Worth + Net income of the period + Net capital gains of the period

The example of Figure 3 is a simple illustration of the impact of capital gains.

The effect of a change in the market value of assets and liabilities may not be accounted in the balance sheet if they are valued on a cost basis. For financial assets, there are three options to record their value. Level 1 valuation uses the available market price. Level 2 valuation, for assets that do not have an active market, uses a proxy market as a point of reference. Level 3 valuation, also called mark-to-model (or more cynically “mark-to-myth”), uses an in-house model to give a dollar value to the asset. During the 2008 crisis, major financial institutions argued that the market prices of some assets did not reflect their true value because of a panic in markets. The Securities and Exchange Commission allowed them to move to level 2 or level 3 valuation to keep up the value of their assets. Many analysts have been critical of this decision and considered it to be a convenient way to hid major losses of institutions.

That is it for today! Following posts will apply all this to banks and central bank.

[Revised 7/21/2016]

ーーーー

☆☆

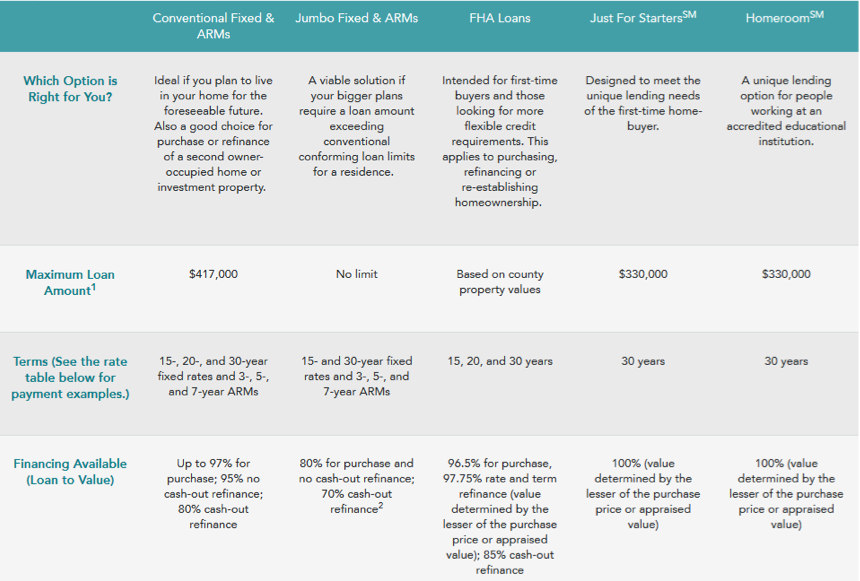

152

通貨、金銭および銀行業

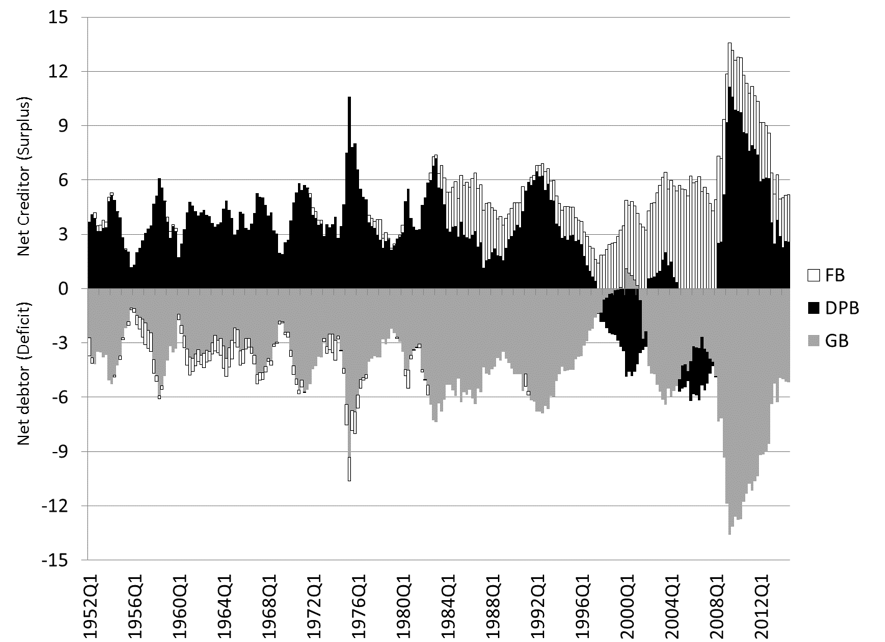

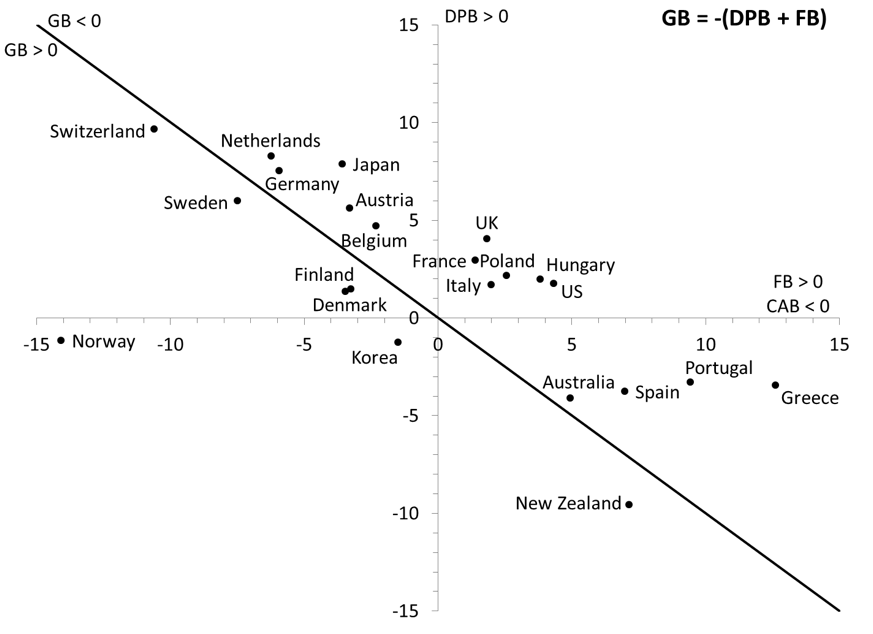

図10.1

米国財務省利回り曲線(2016年2月3日)

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0-

30歳

20歳

3 vr

5歳

10歳

7歳

1カ月

3カ月

6カ月

2歳

出典:著者自身。日次財務省利回り曲線率、リソースセンター、米国財務省からのデータ

(https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/interest-rates/Pages/default asnv)

満期中央銀行は短期金利を上げることによってビルのインフレ圧力に対応するかもしれない

急激に評価します。債券利回りは上がるかもしれませんが、金融政策の大幅な引き締めは短期的な

利子率はより早く上昇し、結果として利回り曲線は逆転する。それからより高い金利はそれから導くかもしれません

経済成長を遅らせるため。

平ら平らな利回り曲線は、正から逆へ、またその逆への移行で最も頻繁に見られます。として

利回り曲線が平らになると、利回りスプレッドはかなり低下します。イールドスプレッドは、例えば、

1年債と10年債の利回り。これは経済の将来の業績について何を示唆しているのでしょうか。

フラットな利回り曲線は、金融引き締め政策(短期金利の上昇)を反映している可能性があります。

景気後退後の金融緩和(短期金利の緩和)なので、逆利回り曲線は平坦化します。

イールドカーブの動きは、経済学者が伝える情報のおかげで、経済学者たちによってよく見守られています。

経済の全般的な健全性、中央銀行の金利調整の可能性、インフレ期待について

非政府部門での活動

公称利子率へのオーソドックスのアプローチ

決定:フィッシャー効果

BOX 10.2

固定された償還価値で固定されたクーポン債を保有することにおける1つのリスクは購買力リスクです。

金利にローンファンドのアプローチを採用している正統派のエコノミストは、

ほとんどの人は後でではなく今を消費することを好むでしょう。忘れられた消費を奨励する

今、貯蓄利回りは市場によって提供されなければなりません。利回りは人ができるようにすることを目的としています

現在犠牲にされているよりも将来的により多くを消費します。しかし、商品やサービスの価格が

その間、インフレは実質消費の増加を完全に一掃する可能性があります。

そのため、実質金利はゼロになります。

1年間で1,000ドルのクーポン国債に投資した人がいるとします。

100ドルの単一クーポン支払い。個人は償還日に1,100ドルを得ることを期待します。

保有期間中に価格が10%上昇すると仮定します。年末には、

以前は1,000ドルの費用がかかっていたが、今では1,100ドルの費用がかかるでしょう。言い換えれば、投資家はノーです

投資の結果として、年末になると好調です。名目利回りは相殺されています。

152

CURRENCY, MONEY AND BANKING

Figure 10.1

US Treasury yield curve (3 February 2016)

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0-

30 yr

20 yr

3 vr

5 yr

10 yr

7 yr

1 mo

3 mo

6 mo

2 yr

Source: Authors' own. Data from Daily Treasury Yield Curve Rates, Resource Center, US Department of the Treasury

(https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/interest-rates/Pages/default asnv)

maturities. The central bank might respond to the building inflationary pressures by raising short-term interest

rates sharply. Although bond yields might rise, the significant tightening of monetary policy causes short-term

interest rates to rise faster, resulting in an inversion of the yield curve. The higher interest rates may then lead

to slower economic growth.

Flat A flat yield curve is seen most frequently in the transition from positive to inverted and vice versa. As

the yield curve flattens, the yield spreads drop considerably. A yield spread is the difference between say, the

yield on a one year and a ten year bond. What does this signal about the future performance of the economy?

A flat yield curve can reflect a tightening monetary policy (short-term rates rise), Alternatively, it might depict

a monetary easing after a recession (easing short-term rates) so the inverted yield curve will flatten out.

Movements in the yield curve are thus closely watched by economists due to the information that they convey

about the general health of the economy, possible central bank interest rate adjustments, and inflationary expect-

ations in the non-government sector

THE ORTHODOX APPROACH TO NOMINAL INTEREST RATE

DETERMINATION: THE FISHER EFFECT

BOX 10.2

One risk in holding a fixed coupon bond with a fixed redemption value is purchasing power risk.

Orthodox economists who adopt the loanable funds approach to interest rates believe that

most people would prefer to consume now rather than later. To encourage forgone consumption

now, a yield on savings must be provided by markets. The yield is intended to allow a person to

consume more in the future than has been sacrificed now. But if the prices of goods and services

increase in the meantime, then inflation could completely wipe out any gain in real consumption,

so that the real interest rate is zero.

Consider a person who invests in a one year $1,000 coupon treasury bond with an expected

single coupon payment of $100. The individual will expect to get $1,100 on the redem ption date.

Assume that over the holding period, prices rise by ten per cent. At the end of the year, a bas-

ket of goods that previously cost $1,000 would now cost $1,100. In other words, the investor is no

better off at the end of the year as a result of the investment. The nominal yield has been offset by

10お金と銀行

153

価格インフレ正統派のエコノミストは、投資家は「本当の」リターンによって動機づけられていると信じています

名目収益率による。これは、彼らが投資するという決定を消費者からのものであると見なしているからです。

現在消費するのか将来消費するのかを選択します。

実際の商品やサービスの形態。そのような貯蓄者がインフレを考慮に入れなければ、彼らの将来の現実は

消費は彼らが望むよりも少なくなります。

正統派のエコノミストは、名目利子率は実質金利と等しくなければならないと提案する

プラス予想インフレ。実質金利は、市場で決定された実質金利であると考えられています。

これは、資金の貯蓄を資金の投資需要と同等にすることになります。それは

したがって、実質均衡金利です。しかし、契約は額面で書かれているので、

名目金利に関しては、名目利子率には期待値に対する補償が含まれていなければなりません。

インフレ率。インフレ期待が上がるにつれて実質金利がこのように増加することをフィッシャーと呼びます。

アメリカの経済学者アーヴィング・フィッシャーに因んで名付けられた。

1930年代多くの市場参加者はこれが債券市場に当てはまると考えており、強い信念があります

名目利回りは購買力を維持するために市場によって調整される

満期が長くなるにつれて購買力リスクが高まる。これが多くのエコノ

ミストは、より長い成熟率が一般的に高くなると信じています。市場の利回りは

実際の収益率と予想インフレ率の補償。インフレの場合

金利は上昇すると予想され、その後市場金利はそれを補うために上昇します。この場合、私たちは期待するでしょう

フィッシャー効果がより長い時間でより大きく影響することを考えると、利回り曲線は急勾配になります。

イールドカーブの最短期間よりも満期のある債券。

10.4銀行は何をするのか

新古典派的見方:貨幣乗数

ほとんどの教科書では、銀行は預金を取り込む小さな仲間を抱える金融仲介機関として提示されています。

準備金の形でこれらの資金を調達し、残りを貸し出す。因果関係は、預金から準備金までです。

ローン各銀行が融資を行う際にこれらの原則に従うと、総融資は「預金」を通じて拡大します。

またはお金乗数。今のところ、すべての銀行が準備金の比率を維持する必要があると仮定します。

10パーセントの預金。これは彼らがから生じる準備金の損失に容易に対応できるようにするためかもしれません。

売り手が他の銀行に預けている顧客または(たとえば、商品やサービスへの)支出、または保有しようとしている顧客。

追加の現金。

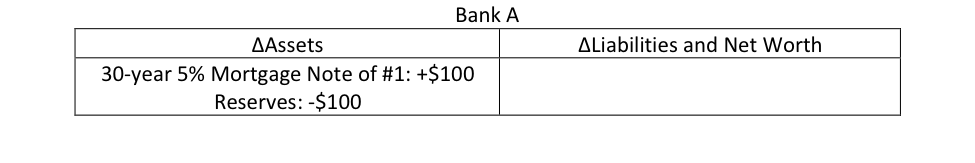

これが新古典派学派が貨幣乗数の運用を説明する方法です

i)顧客が銀行Aに100ドルを預けるとします。

i)銀行Aは、10パーセントの必要な準備金に対する預金の比率に合わせるために、10ドルの準備金を留保します。に

ローンポートフォリオを拡大して利益を増やすと、残りの90ドルは

90ドル上昇します。

ii顧客はこれらの預金を使い、資金の受取人(売り手)は銀行Bに90ドルを預ける。

iv)その後、銀行Bは、0.9 X $ 90 = 81 $(必要に応じて10%、つまり追加準備金として9 $を維持)を貸し出す。

彼らの支出などを融資する顧客。

預金がある顧客

各段階で、貸し出されてから費やされる額が減少します。

銀行システムが作動し、その後900ドルの追加ローンが作成されます。最初の新規入金では、これは

預金は合計で1,000ドル増加しており、100ドルの準備金で「後退」しているため、必要額に適合しています。

10パーセントの割合。

この例は、主流の教科書がフラクショナルリザーブ銀行システムを呼んでいるものです。それが目的とする

銀行がどのようにしてお金を生み出すのかを説明する。これは、現在の預金の増加により、M1のマネーサプライを増やす。

初回入金額100ドルに関して、乗数は10です。これは、必要な準備金の逆数です。

0.1の比率。次の場合に非政府部門がより多くの現金を保有することを選択した場合は、より小さな資金倍率が得られます。

貸方が作成されます。

10 Money and Banking

153

the price inflation. Orthodox economists believe that investors are motivated by 'real' returns, not

by nominal returns. This is because they view the decision to invest as coming from consumers

who choose whether to consume now or to consume in the future, with consumption taking the

form of real goods and services. If such savers do not take account of inflation, their future real

consumption will be less than they desired.

Orthodox economists propose that the nominal inte rest rate must equal a real interest rate

plus expected inflation. The real interest rate is supposed to be the market-determined real

return that will equate the saving supply of funds with the investment demand for funds. It is

thus a real equilibrium interest rate. However, as contracts are written in nominal terms, that is,

in terms of nominal interest rates, the nominal rate must include compensation for the expected

inflation rate. This addition to the real rate as inflation expectations rise is called the Fisher

effect, named after the American economist Irving Fisher, who identified this relationship in the

1930s. Many market participants believe this applies to bond markets, and there is a strong belief

that nominal yields are adjusted by markets to preserve purchasing power

Purchasing power risk increases as the maturity lengthens. This is one reason many econo-

mists believe that longer maturity rates will generally be higher. The market yield is equal to the

real rate of return required plus compensation for the expected rate of inflation. If the inflation

rate is expected to rise, then market rates will rise to compensate. In this case, we wou ld expect

the yield curve to steepen, given that the Fisher effect will impact more significantly on longer

maturity bonds than at the short end of the yield curve.

10.4 What Do Banks Do?

The neoclassical view: the money multiplier

In most textbooks, banks are presented as financial intermediaries that take in deposits, hold a small frac

tion of these in the form of reserves, and lend out the remainder. The causality is from deposits to reserves to

loans. If each bank follows these principles in making loans, aggregate lending expands through the 'deposit

or money multiplier. For the moment assume that all banks are required to maintain a ratio of reserves to

deposits of ten per cent. This might be to enable them to readily respond to a loss of reserves resulting from

spending by customers (on goods and services, say) whose sellers bank elsewhere, or customers seeking to hold

additional cash.

This is how the neoclassical school of thought describes the operation of the money multiplier

i) Assume that a customer deposits $100 in Bank A;

i) Bank A retains $10 of reserves to conform to the required reserves-to-deposit ratio of ten per cent. To

expand its loan portfolio and increase profits, the remaining $90 is loaned to

rise by $90;

ii The customer spends these deposits and the recipient of the funds (seller) deposits $90 in Bank B;

iv) Bank B then lends 0.9 X $90 = $81 (keeping ten per cent, that is, $9 as additional reserves, as required) to a

customer to finance their expenditure and so on.

customer whose deposits

At each stage the amount lent and then spent diminishes, It can be readily shown that if this was the way the

banking system operated, then $900 of additional loans are created. With the initial new deposit, this means that

deposits have risen by a total of $1,000 and are 'backed' by $100 of reserves, thereby conforming to the required

ten per cent ratio.

This example is what the mainstream textbooks call a fractional reserve banking system. It purports to

explain how banks create money, which increases the M1 money supply due to the increase in current deposits.

In terms of the initial deposit of $100, the multiplier is 10, which is the inverse of the required reserves-to-deposit

ratio of 0.1. A smaller money multiplier results if the non-government sector chooses to hold more cash when

credit is created.

10お金と銀行

155

銀行の管理者は一般的に、銀行システムの積立金の総計レベルを知らず、気にすることもありません。

確かに、ローンを承認する前にローン担当者が個々の銀行の準備ポジションをチェックすることは決してありません。銀行貸出 -

意思決定は、準備金のポジションではなく、準備金の価格と予想収益の影響を受けます。スプレッドが

資産(証券またはローン)の収益率と準備金の借入コストの間の幅が十分に広い

すでに準備金が不足している銀行でさえ、資産を購入するかローンを作り、準備金をまかなうでしょう。

インターバンク市場で準備金を購入することによって必要とされる。銀行間市場は銀行を結ぶ

必要に応じて、お互いに準備金を貸したり借りたりします。

重要な点は、銀行が企業や世帯に融資をするとき、それは準備金を貸すことではないということです。

銀行の貸出は、準備金が増えればそれほど困難ではないのと同様に、準備金が増えれば簡単にはなりません。銀行の準備金はありません

お金の乗数と端数準備金の物語で主張されている方法でお金の創造に資金を提供する。

銀行は、融資する前に入金が来るのを待ちません。

銀行と他の種類の企業との主な違いは、負債の性質にあります。銀行が作る

「借り手」のIOUSを購入することによる「融資」。これは銀行の負債、通常要求払預金を、少なくとももたらす、

当初、それは借り手の資産として現れます。したがって、ローンを担保している銀行の顧客は同時に存在します。

EV

デマンドデポジットを保有しているため、銀行の「債権者」であるだけでなく、銀行への「債務者」でもあります。これらの債権者

交換媒体として新しく作成された要求払預金を使用する彼らの権利をほぼ即座に行使する

商品やサービス、または資産の購入用。銀行負債(銀行預金)は世帯によって使用され、

小切手または振替の形での取引のための銀行会社。顧客はまた、で要求払預金を引き換えることができます。

現金の使用を可能にするために、フィアットマネー(政府によって保証されています)に対する額面金額(ドル/ドル)

支払いまたは支払いをすること。政府はまた、いくつかの種類の銀行負債を

税金の支払い

一方、銀行の準備金は、銀行間の支払い(または銀行間決済)および支払いに使用されます。

中央銀行に行った。したがって、銀行の「債権者」が支出または

より多くの現金を保有することを選択すると、個々の銀行に対する準備金の対応する損失が生じる。銀行はそれから

資産の売却またはその負債の増加(追加の準備金の借入)により、準備金の損失を補填します。

銀行間市場(米国では連邦資金市場と呼ばれる)は、次のような準備金残高をシャッフルするように機能します。

加盟(民間)銀行は中央銀行と協力して、これらの各銀行がその準備金を満たすことができるようにする。

指定された期間の終わりには、単純にゼロの残高になる可能性があります。

日であると仮定することができます)。しかしながら、全体として、そのような活動は準備金をある銀行から別の銀行に移すだけです。もっとあれば

準備金は合計で必要とされ、それらは中央銀行によって供給されなければなりません。

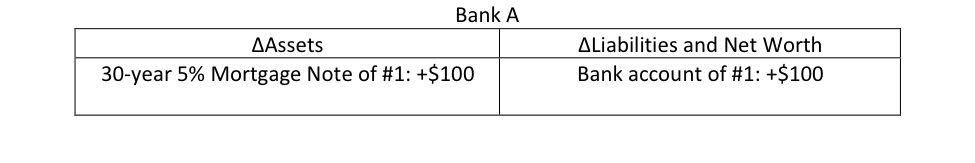

彼らがローンを作る前に預金を待つことからかけ離れて、現実の世界の銀行は彼らの貸借対照表を拡大する

下記のように貸し出し

ローンは預金を作成します

ローンは預金を生み出し、それは事後に積立金によって裏付けられます。ローン(クレジット)を拡大するプロセス

これは新しい銀行負債を生み出し、銀行の準備金ポジションとは無関係です。利益の追求では、

銀行は融資を求め、正当性に従ってそれらを評価する信用力のある顧客から申請書を受け取ります

2008年の世界金融危機へのリードアップではあるが、検証プロセスは

とてもゆるい

銀行の融資部門が信用を拡大することを禁じる唯一のことは、信用できる申請者がいないことです。

これは、悲観論の時代に銀行が適格基準を引き上げたことによるものか、または信用できる場合に発生する可能性があります。

顧客は将来の不確実性のためにローンを探すのが嫌です

主な洞察は、必要な準備金が銀行に残されているバランスシートの拡大は、

それがローンに期待できるリターンに影響を与えます。これは中央銀行が正当化するかもしれない「ペナルティ」率の結果です

割引窓口(引当金を必要とする銀行への貸付のための中央銀行の施設)を通して

それがそれに対する請求をカバーするためにそれが日の終わりに必要とする準備金に足りません。しかし、それは妨げることは決してないだろう

そもそも融資を行う銀行の能力。したがって、中央銀行が可能であると仮定することはまったく間違っています。

より多くの準備金をシステムに追加することによって、銀行が信用を拡大する能力に影響を与えます。これに対処します

第23章でより詳細な命題

10 Money and Banking

155

Bank managers generally neither know, nor care, about the aggregate level of reserves in the banking system.

Certainly, no loan officer ever checks the individual bank's reserve position before approving a loan. Bank lend-

ing decisions are affected by the price of reserves and expected returns, not by reserve positions. If the spread

between the rate of return on an asset (a security or a loan) and the cost of borrowing reserves is wide enough,

even a bank that is already deficient in reserves will purchase the asset or make a loan and cover the reserves

needed by purchasing (borrowing) reserves in the interbank market. The interbank market connects the banks

which lend reserves to and borrow reserves from each other when needed.

The important point is that when a bank originates a loan to a firm or a household, it is not lending reserves.

Bank lending is not easier if there are more reserves, just as it is not harder if there are less. Bank reserves do not

fund money creation in the way that is claimed in the money multiplier and fractional reserve deposit story;

banks do not wait for deposits to come in before they make loans.

The main difference between banks and other types of firms involves the nature of the liabilities. Banks 'make

loans' by purchasing the IOUS of 'borrowers'. This results in a bank liability, usually a demand deposit, at least

initially, that shows up as an asset of the borrower. Thus, a customer of a bank who secures a loan is simultan-

ev

eously a 'creditor' of the bank, due to holding a demand deposit, but also a 'debtor' to the bank. These creditors

will almost immediately exercise their right to use the newly created demand deposits as a medium of exchange

for purchases of goods and services, or assets. Bank liabilities (bank deposits) are used by households and non-

bank firms for transactions in the form of cheques or transfers. Customers can also redeem demand deposits at

par (dollar for dollar) against fiat money (which is guaranteed by the government) to enable cash to be used for

purchases or making payments that are due. The government will also accept some kinds of bank liabilities in

payment of taxes

In turn, bank reserves are used for payment (or interbank settlement) among banks and for payments

made to the central bank. Thus, when bank 'creditors' draw down their demand deposits, by either spending or

choosing to hold more cash, a corresponding loss of reserves for the individual bank results. The bank may then

either sell an asset or increase its liabilities (borrowing additional reserves) to cover the loss of reserves.

The interbank market (called the federal funds market in the US) functions to shuffle the reserve balances that

the member (private) banks keep with the central bank to ensure that each of these banks can meet its reserve

targets, which might be simply zero balances at the end of a specified period of time (that for simplicity, we

could assume is a day). In aggregate, however, such activities only shift reserves from one bank to another. If more

reserves are needed in total, they must be supplied by the central bank

Far from waiting for deposits before they create loans, banks in the real world expand their balance sheets by

lending as described below

Loans create deposits

Loans create deposits that are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit),

which creates new bank liabilities, is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank. In the pursuit of profit,

banks take applications from creditworthy customers who seek loans and assess them according to the verity

of the application, although in the lead-up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the validation process became

very lax

The only thing that constrains the bank loan desks from expanding credit is a lack of creditworthy applicants,

which can be due to banks raising the qualifying standards in times of pessimism, or can occur if creditworthy

customers are loath to seek loans because of future uncertainty

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion that leaves a bank short of the required reserves may

affect the return it can expect on the loan. This is a consequence of the 'penalty' rate the central bank might exact

through the discount window (the central bank facility for lending to banks in need of reserves) should the bank

fall short of the reserves it requires at the end of the day to cover the claims on it. However, it will never impede

the bank's capacity to make the loan in the first place. It is thus quite wrong to assume that the central bank can

influence the capacity of banks to expand credit by adding more reserves into the system. We will address this

proposition in more detail in Chapter 23

156

通貨。お金と銀行

銀行は準備金を貸し出さない

「ローンが預金を生み出す」という洞察の必然的な結果は、銀行が準備金を貸し出していないということです。

銀行の準備金は実際にどのような役割を果たしているのでしょうか。

銀行は、支払いシステムの一環として、中央銀行との間で準備金を計上しなければなりません。引当金が使用されます

銀行間支払いをする。毎日、これらの銀行間取引を通じて何百万もの取引が調整(決済)されています

支払い例えば、銀行Aに引き出され、銀行Bに預け入れられた小切手は、銀行から送金された資金を見るでしょう。

Aの準備金は銀行Bのそれにバランスをとります

特定の銀行がそれ自体に対してすべての日々の請求を解決するのに必要な準備金の量に足りないと判断した場合

それから、それは最初に他の銀行からの準備金を借りてみることができます。

その特定の日の要件。しかし、20章と23章で見るように、全体的な不足(あるいは過剰)は

銀行システム全体にわたる準備金は、銀行に準備金を提供する中央銀行によって修正されなければならない(

不足の場合)、または過剰の場合はシステムからそれらを排出することがあります。この中央銀行の介入は

我々が流動性管理の役割と呼んでいるものであり、銀行が準備金の全体的な水準を管理することを可能にしている。

その金利目標と一致している。例えば、ある特定の日に過剰な準備金がある場合

(取引を決済するのに必要な量を超えて)そして中央銀行はいかなる競争力も提供しない。

彼らに還元し、それらの超過を保有している銀行はそれらを運転する効果を持っている夜通しそれらを貸し出すことを試みるでしょう

短期金利を引き下げます。中央銀行はこれらの準備金を(国債を

銀行は、夜間の銀行間金利を維持するために、準備金口座への引き落としを行います。

目的のポリシー(ターゲット)レートと同じです。これについては23章でさらに学びます。

そのこと

内生的なお金

私たちは、新古典派の教科書に載っている物語とは異なり、現実世界では中央銀行は

マネーサプライを管理しないでください。言い換えれば、貨幣供給は内生的な貨幣であり、

銀行資金の供給は、銀行の融資に対する需要と銀行の意欲によって「内生的に」決定される

貸す(預金の作成を引き起こす)。新古典派理論は、お金が

供給は外因性であり、貨幣ベースと相互作用する貨幣乗数を通じて決定される。

新古典派は中央銀行の管理下にあると信じる

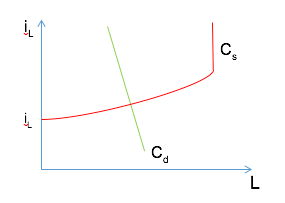

銀行ローンに対する需要は、民間経済主体(以下を含む)の支出決定によって決まる。

資産購入に関する決定を行うこと。これらの影響を受ける可能性がありますが、非常に間接的にのみ、

興味があります。銀行は、誰かがにIOUを発行することによって銀行のお金を「借りる」ことを喜んでいるという理由だけでローンを供給します

銀行。これは、金利が貸付金の供給と需要によって決定できないことを意味します。

需要と供給は独立していません。むしろ、銀行は短期の個人向け貸付市場における価格設定者です。

それから彼らはある量の配給量でローンの需要を満たす

希望のある借り手が進んで支払うことができると思っている場合でも、ローンの要求は拒否されます。

その価格で。言い換えれば、いくつかの

金利。

人口の大部分をこのように数量配分する理由はいくつかあります。銀行

借り手の債務不履行リスクを心配するかもしれませんが、金利を引き上げることができないかもしれません。

デフォルトリスクをカバーするのに便利です。量配給は価格配給よりも優れています。

いくつかの借り手に課される金利。また、銀行はおそらく借り手よりも優れた情報を持っています

デフォルトリスクについて。例えば、新しいレストランを開くことを望む借り手は、確信を持っていないかもしれません。

業界の倒産率に関する情報を評価したり、単に楽観的すぎる可能性があります。もう一方の

一方で、銀行は未来を知ることができないので、経験則に基づいて行動しなければならない(例:非公式)

ローンの規模を制限する規則)いくつかの数量配給は、理にかなっていない、おそらく差別的にさえなり得ます。

銀行は伝統的に特定の種類のローンを放棄してきたか、企業内の特定のグループに貸し出すことに消極的である。

自治体。重要な点は、融資の供給が単に融資需要に合わせて調整されていないことです。

金利。

短期小売金利は、短期卸売金利に対する値上げと見なすことができます。まさに

マークアップを決定するもの(およびそれが可変かどうか)は物議を醸していますが、ここでの分析には重要ではありません。

(ムーア、1988年を見なさい)。

156

CURRENCY. MONEY AND BANKING

Banks do not loan out reserves

A corollary of the 'loans create deposits' insight is that banks do not loan out reserves, which raises the question

of what role do bank reserves actually play?

Banks must hold reserve balances with the central bank as part of the payments system. The reserves are used

to make interbank payments. Each day millions of transactions are reconciled (settled) through these interbank

payments. For example, cheques drawn on Bank A and deposited at Bank B will see funds transferred from Bank

A's reserve balances to those of Bank B

If a particular bank finds itself short of the quantity of reserves necessary to resolve all the daily claims against

it, then it can first try to borrow reserves from other banks that might have excess reserves in relation to their

requirements on that particular day. But, as we will see in Chapters 20 and 23, an overall shortage (or excess) of

reserves across the banking system must be rectified by the central bank which provides reserves to banks (in the

case of a shortage) or may drain them from the system in the case of an excess. This central bank intervention is

what we refer to as its liquidity management role and allows the bank to manage the overall level of reserves so

s consistent with its interest rate target. For example, if on any particular day there is an excess of reserves

(over and above the quantity required to settle transactions) and the central bank does not offer any competitive

return on them, banks holding those excesses will try to loan them out overnight, which has the effect of driving

down the short-term interest rate. The central bank must drain those reserves (by selling government bonds to

the banks in return for debits to the reserve accounts) to ensure the overnight interbank interest rate remains

equal to its desired policy (target) rate. We will learn more about this in Chapter 23.

that it

Endogenous money

We have stated that unlike the story presented in neoclassical textbooks, in the real world the central bank can-

not control the money supply. In other words, the money supply is endogenous money in the sense that the

supply of bank money is determined 'endogenously' by the demand for bank loans, plus the willingness of banks

to lend (which gives rise to the creation of deposits). The neoclassical theory erroneously believes that the money

supply is exogenous and determined through the money multiplier interacting with the monetary base, which

neoclassicists believe to be under the control of the central bank

The demand for bank loans is determined by the spending decisions of private economic agents (includ-

ing decisions regarding asset purchases). These can be affected, but only very indirectly, by the loan rate of

interest. Banks supply loans only because someone is willing to 'borrow' bank money by issuing an IOU to

banks. This means that the interest rate cannot be determined by the supply of and demand for loans since

supply and demand are not independent. Rather, banks are price setters in short-term retail loan markets

They then meet the demand for loans with some quantity rationing

requests for loans are refused, even where aspiring borrowers claim to be willing and able to pay the going

at that price. In other words, some

interest rate.

There can be several reasons for such quantity rationing of large segments of the population. Banks

might worry about the default risk of some borrowers but might not be able to raise interest rates suffi-

ciently to cover the default risk. Quantity rationing is then superior to price rationing, that is, raising the

interest rate charged to some borrowers. Also, banks probably have better information than do borrowers

about default risks. For example, the borrower who wishes to open a new restaurant might not have accu-

rate information about bankruptcy rates in the industry or might simply be overly optimistic. On the other

hand, banks can never know the future, so must operate based on rules of thumb (for example, informal

rules that restrict loan size). Some quantity rationing can even be irrational, perhaps discriminatory, because

banks have traditionally forgone certain kinds of loans or are reluctant to lend to certain groups in the com-

munity. The key point is that the supply of loans does not simply adjust to the demand for loans at some

interest rate.

The short-term retail interest rates can be taken as a mark-up over short-term wholesale interest rates. Exactly

what determines the mark-up (and whether it is variable) is controversial, but not important to our analysis here

(see Moore, 1988).

10お金と銀行

卸売金利は、最後に、中央銀行の政策の影響下にあります。個々の銀行は卸売を使用しています

個人向けローンと預金のミスマッチを是正するための市場。ほとんどの銀行は正確に調整できないでしょう

彼らの小売ローンと預金。銀行によっては、預金に留めることができるよりも多くの個人向け貸付を行うことができるようになるでしょう。

他の人が預金者よりも少ないローンの顧客を見つける一方で、したがって、準備金の損失を被るので、彼らは

準備金の剰余金。銀行は卸売市場を利用して、卸売負債を発行して準備金を「購入」します。

(例えば、交渉可能な大額面の預金証書(CD)、または中央銀行の資金を借りることによって)

余剰銀行は余剰準備金を売却します。

上述のように、中央銀行は一晩の銀行間金利を設定する。それからこの率は他の不足を決定します

アービトラージによる長期卸売利率(主に値上げによるが、値下げによる)。

157

概要

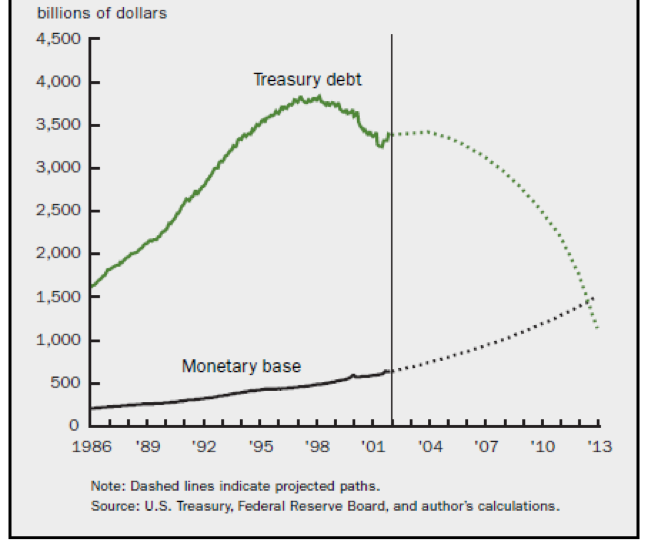

新古典派の立場は、新しい預金が提供されると銀行は活用する(信用を生み出す)が

端数準備金の要件により制約を受ける。中央銀行はおそらく通貨を管理することができるので

基本的には、中央銀行が貨幣の供給を管理できると主張している。

MMTは、現実の世界で何が起きているのかを反映して、中央銀行が金融機関を統制できないことを示しています。

なぜなら、金融政策は中央銀行が目標の銀行間金利と所得を設定することによって行われるからである。

銀行がこの時点で互いに貸し借りできるように、適切な水準の準備金を銀行システムに割り当てる

目標レート(詳細については、第20章と第23章を参照)。第二に、銀行はその準備金のポジションに制約されていません。

特定の顧客に融資を行うかどうかを決定します。

銀行にとって利益がある、それはローンを作り、そして他の銀行から借りることによって十分な準備金を獲得するでしょう

または中央銀行。したがって、ローンを推進する預金の新古典主義の立場とは対照的に、MMTはローン

預金を促進する。第三に、総合的なマネーサプライの成長は、まとめて言えば、融資の需要と

通貨ベースは、内生的な金融成長が中央銀行に与える圧力に適応しています。

特定の政策金利を維持するというその探求。それ故にお金の供給は内生的に決定されます

貨幣の価格(短期金利)は、中央銀行の政策によって外的に決定されます。

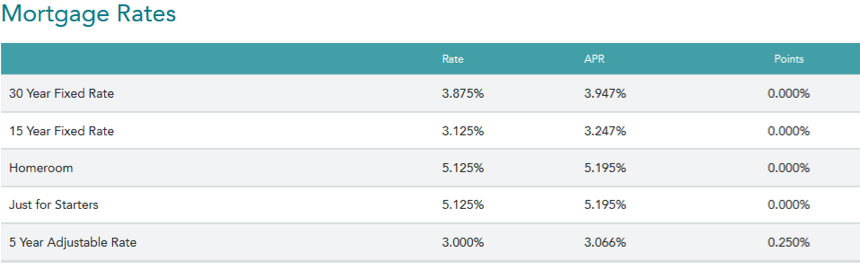

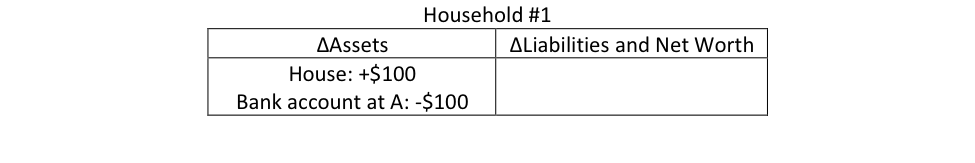

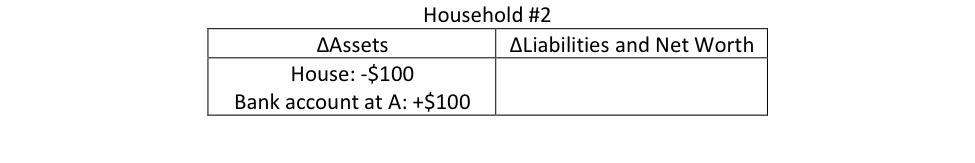

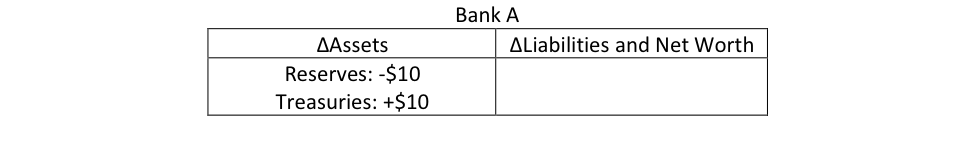

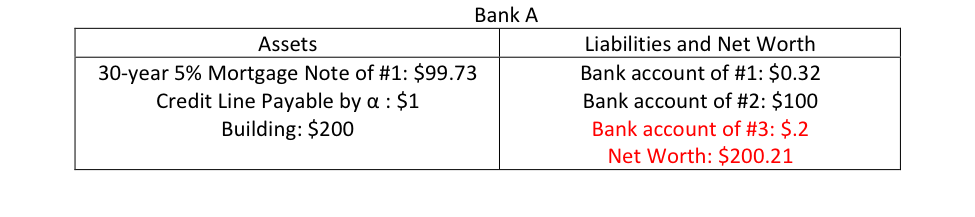

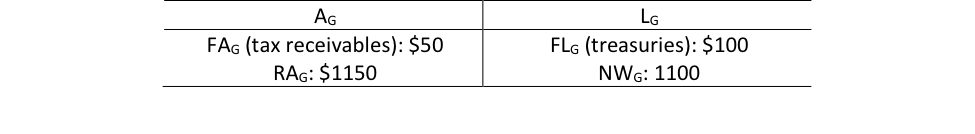

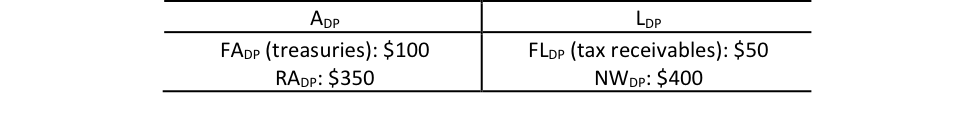

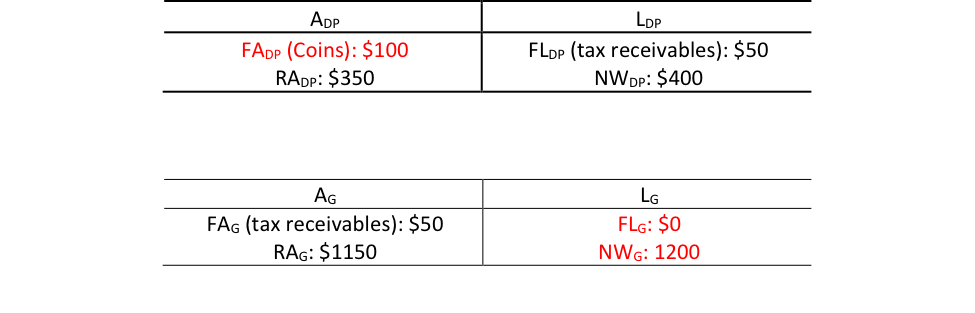

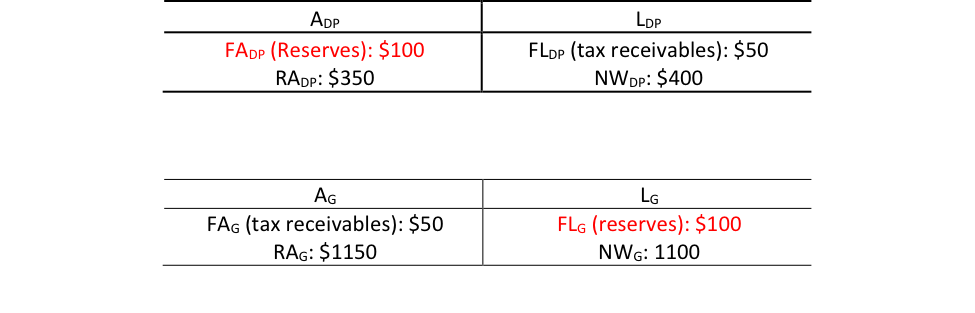

銀行の信用創造の一例:バランスシート分析

典型的な銀行の貸借対照表は、図10.2のようになります。

貸借対照表のエントリは、小切手と普通預金です。彼らは銀行のIOUSであることに注意してください

したがって、負債として表示されます。銀行は、小切手口座の預金(およびほとんどの国の預金

貯金口座)をオンデマンド現金に変換します。銀行は、金融資産を顧客への貸付および証券の形で保有しています。

ities(つまり、国債やその他の金融資産)

一般的な会社と銀行は、正味の純資産を持つべきです。

負債合計左側の列の総資産は、負債の列の項目と釣り合います。

後者は純資産を含みます。

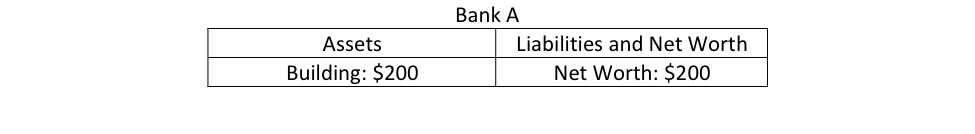

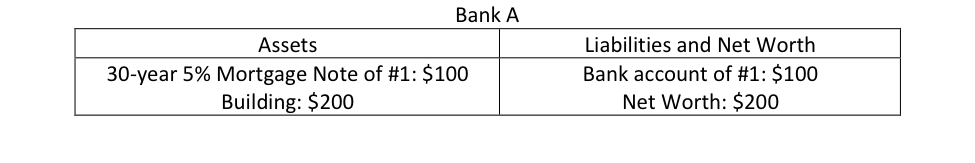

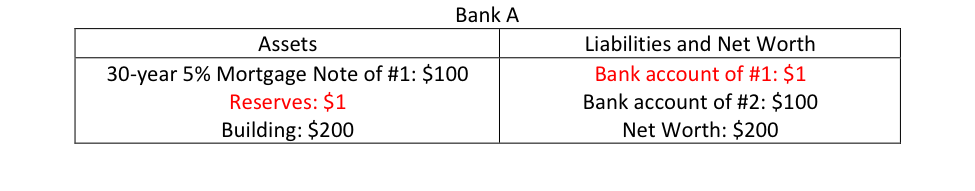

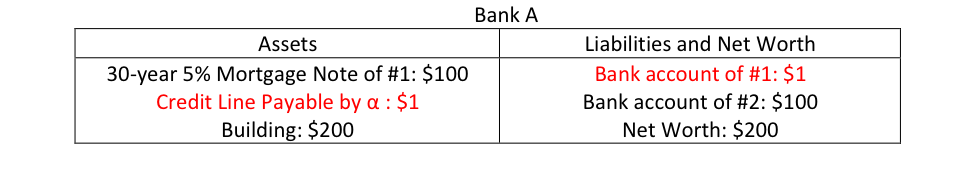

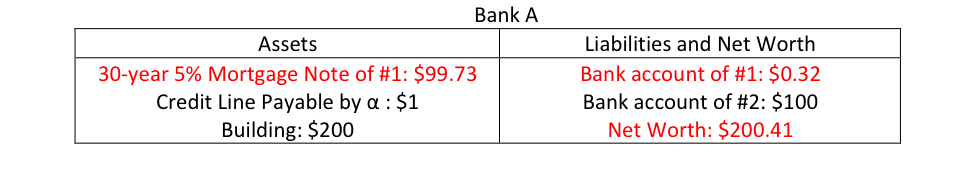

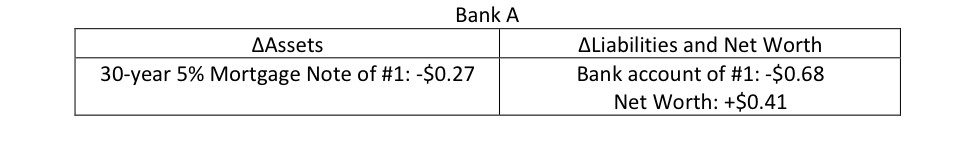

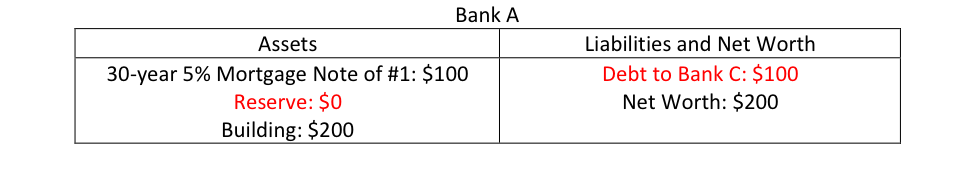

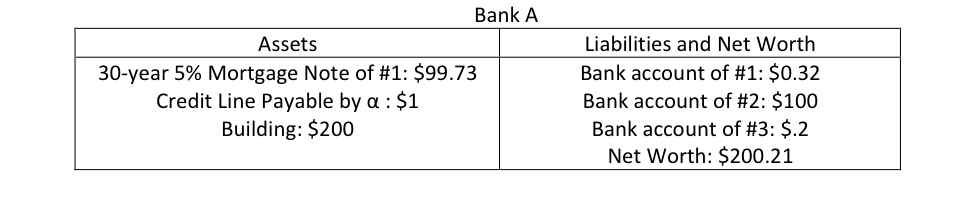

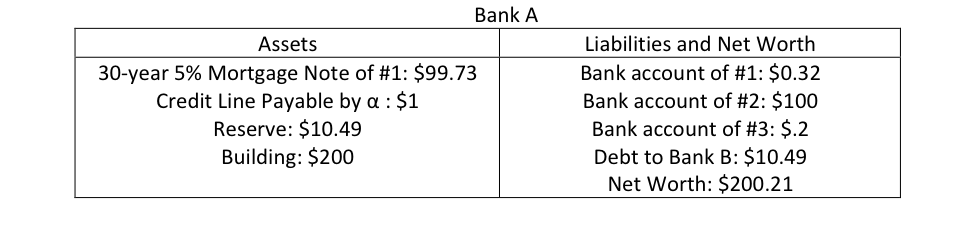

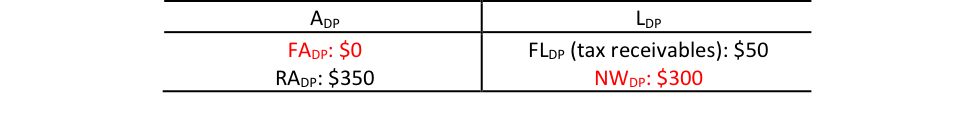

以下の一連の単純化された一連の貸借対照表は、銀行Aによる信用創造のプロセスを明確にするでしょう。

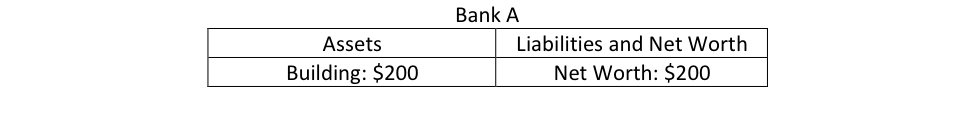

A銀行が図10.3の非常に単純な貸借対照表から始まると仮定します。

典型的な銀行バランスシート

図10.2

負債

資産

アカウントを確認する

普通預金口座

その他の債務

前払(ローン)

証券

引当金

その他の資産

純資産

10 Money and Banking

Wholesale interest rates, finally, are under the influence of central bank policy. Individual banks use wholesale

markets to rectify a mismatch between retail loans and deposits. Most banks will not be able to exactly reconcile

their retail loans and deposits. Some banks will be able to make more retail loans than they can retain in deposits

and thus suffer a loss of reserves, while others will find fewer loan customers than depositors, so they will have a

surplus of reserves. Banks then use wholesale markets to either 'purchase' reserves by issuing wholesale liabilities

(for example, negotiable, large denomination certificates of deposit (CDs) or by borrowing central bank funds),

while surplus banks will sell their excess reserves.

As discussed above, the central bank sets the overnight interbank rate. This rate then determines other short-

term wholesale rates (mainly by marking up, but also by marking down) through arbitrage.

157

Summary

The neoclassical position is that banks leverage (create credit) when provided with new deposits, but are con-

strained by fractional reserve requirements. Since the central bank is supposedly able to control the monetary

base, it is claimed that the central bank can control the supply of money.

Reflecting what happens in the real world, MMT demonstrates that the central bank cannot control the mon-

etary base, because monetary policy is conducted by the central bank setting a target interbank rate and provid-

ing the right level of reserves to the banking system so that banks lend to and borrow from each other at this

target rate (for more details, see Chapters 20 and 23). Second, a bank is not constrained by its reserve position in

deciding whether to make a loan to a particular customer, If the customer appears creditworthy and the loan is

profitable to the bank, it will make the loan and then acquire sufficient reserves by borrowing from other banks

or the central bank. Thus, in contrast to the neoclassical position of deposits driving loans, MMT shows that loans

drive deposits. Third, taken together, the growth in the broad money supply is driven by the demand for loans and

the monetary base adjusts to the pressures that the endogenous monetary growth places on the central bank in

its quest to sustain a particular policy interest rate. Hence the supply of money is determined endogenously while

the price of money (short-term interest rate) is determined exogenously by central bank policy.

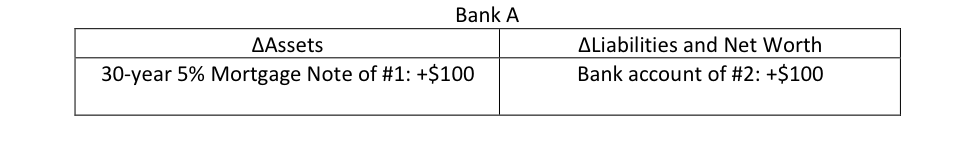

An example of a bank's credit creation: a balance sheet analysis

The balance sheet of a typical bank looks like that in Figure 10.2.

The entries on the balance sheet are the cheque and savings accounts. Note that they are the IOUS of banks

and hence appear as liabilities. The bank promises to convert deposits in a cheque account (and deposits in most

savings accounts) into cash on demand. Banks hold financial assets in the form of loans to customers and secur-

ities (that is, treasury debt and other financial assets)

Firms in general and banks should have positive net worth, which is the difference between total assets and

total liabilities. Total Assets in the left-hand column will balance with the items in the Liability column, because

the latter includes net worth.

The following simplified series of balance sheets will clarify the process of credit creation by Bank A. Let us

assume that Bank A starts with the very simple balance sheet in Figure 10.3, which is expressed in terms of stocks.

A typical bank balance sheet

Figure 10.2

Liabilities

Assets

Cheque accounts

Savings accounts

Other liabilities

Advances (loans)

Securities

Reserves

Other assets

Net worth

158

通貨、金銭および銀行業

図10.3

銀行Aの初期貸借対照表

負債

資産

$ 200

$ 200

建物

純資産

その所有者は資金を調達し、建物を買いました。所有者の自己資本または純資産は価値と等しい

彼らが購入した建物の。 A銀行はまだ銀行業務をしていません。

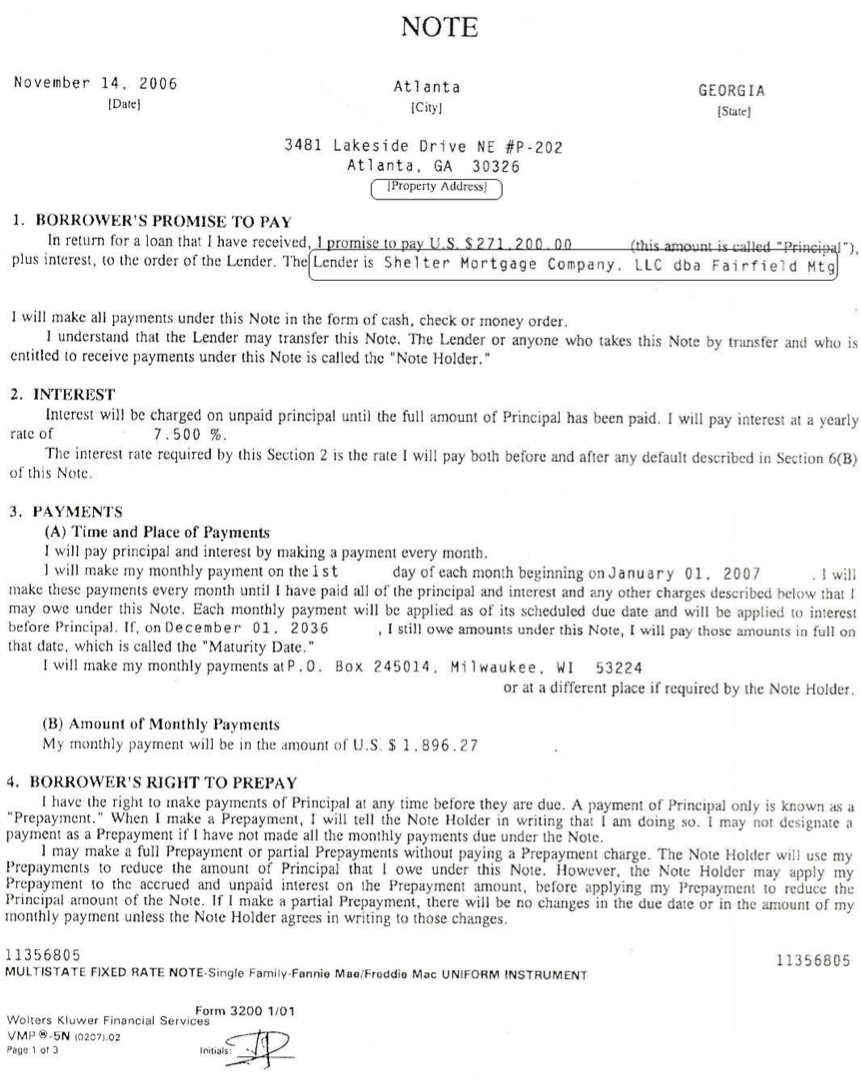

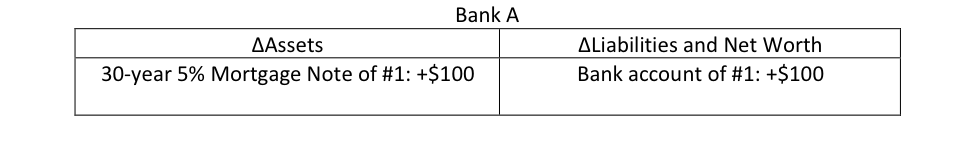

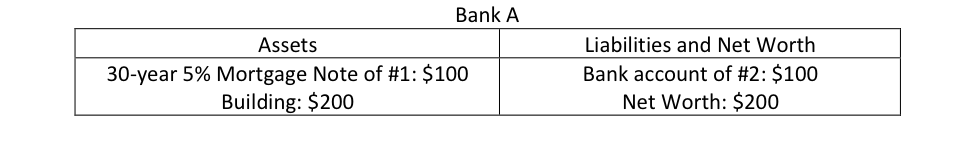

今顧客が銀行に入ってきて、彼らが購入の資金を調達するために200ドルを借りたいと言っている

車。銀行は、所得税申告書、資産の証明、信用履歴、および

そうです。顧客が承認されると、銀行の貸借対照表は図10.4に示す形式になります。

銀行はちょうど200ドルの入金(見返りに顧客の小切手口座への入金)を作成した。

顧客のIOUのために、または200ドルを支払うことを約束)。銀行の総資産、負債と純資産は、

今400ドル。

顧客の預金の支出に移る前に、このバランスシートを慎重に検討しましょう。

銀行は、自分が作成した入金をどこで入手しましたか?

小切手口座はex nihiloで作成されました。つまり、何もない状態から、コンピュータの元帳に数値(200)を入力することによって作成されました。

借り手に代わって。過去には、銀行は独自の紙幣を発行することもできましたが、一般的に

銀行は今それをすることができます。

銀行は、事前の入金や金庫内の現金を必要としませんでした。実際、銀行には現金がありませんでした。

この単純化された例では、金庫も中央銀行の口座に預金がありませんでした。

銀行は自分が持っているものを貸しているのではなく、自由にお金を入れること(つまり銀行の預金)をするだけです。

これらのお金の入金またはエントリーは、その負債/ IOUです。

これらの銀行IOUSを作成することで、銀行は次のことを約束します。

デポジットをオンデマンドで現金に変換します。

- 銀行に負っている借金の支払いでそれらのIOUSのいずれかを受け入れます。

当座預金口座は、オンデマンドで現金に変換し、次の形式で支払いを受け取ることを法的に約束したものです。

銀行自身のIOUS銀行は今現金を持っている必要はありません。

銀行業務の成功(IOUの受け入れによる貸し出し、および要求払いの作成)

に依存します:

顧客が返済する能力、つまり彼らの信用力。タイムリーに作るのに問題があるのなら

彼らの借金の支払いは、これは銀行の資産の価値に影響を及ぼし、それ自身の収入は流入し、最終的には

銀行の自己資本、銀行の自己資本比率、および株主資本利益率に影響します。

銀行が低コストで準備金を取得する能力

顧客は現金を引き出すことを望んでいます。

- 銀行は、顧客の後に銀行間決済を通じて他の銀行に借金を支払う必要があります。

支出(下記参照)

- 銀行は、顧客から政府に支払われた納税を決済する必要があります。

これらの条件が満たされない場合

銀行はトラブルに巻き込まれる:それはなることができます

支払不能または流動性がない。倒産の意味

銀行の自己資本が

ゼロ以下;非流動性

ローンを示す銀行Aの貸借対照表

図10.4

負債

資産

得意先の小切手口座

+ 200ドル

それはそれを意味する

現金引き出しに対応できない

清算。したがって、銀行ができても

無制限のお金を生み出す

顧客への貸付

+ 200ドル

$ 200

建物

純資産

$ 200

158

CURRENCY, MONEY AND BANKING

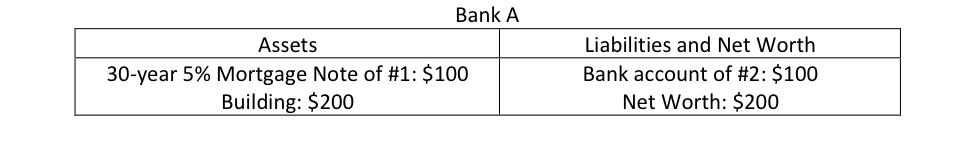

Figure 10.3

Bank A initial balance sheet

Liabilities

Assets

$200

$200

Building

Net worth

Its owners have raised capital and bought the building. The owner's equity or net worth is equal to the value

of the building that they have purchased. Bank A has not engaged in any banking activity yet.

Now a customer comes into the bank and says that they would like to borrow $200 to finance the purchase of

a car. The bank checks their creditworthiness by asking for income tax returns, proof of assets, credit history, and

so on. If the customer is approved, then the bank's balance sheet takes the form shown in Figure 10.4.

The bank just created $200 of money entries (deposits in the cheque account of the customer in return

for the customer's IOU, or promise to pay $200). The bank's total assets, liabilities plus net worth, are

now $400.

Before we move on to the customer's spending of their deposit, let us examine this balance sheet carefully

Where did the bank get the money entry it created?

A cheque account was created ex nihilo, that is, from nothing, by entering a number (200) in a computer ledger

on behalf of the borrower. In the past, banks could also issue their own banknotes, but generally only central

banks can do that now.

The bank did not need any prior deposits, or any cash in its vault. In fact, the bank did not have any cash in its

vault, nor did it have any deposits in its account at the central bank in this simplified example.

The bank is not lending anything it has, it just creates money entries (that is, bank deposits), at will.

Those money deposits or entries are its liabilities/IOU..

By creating those bank IOUS, the bank promises to:

Convert deposits into cash on demand;

- Accept any of those IOUS in payment of debts owed to the bank.

The cheque account is just a legal promise to convert to cash on demand, and to accept payment in the form of

the bank's own IOUS. The bank does not have to have any cash now.

The success of the banking operation (lending by accepting an IOU, and the creation of a demand deposit)

depends on:

The capacity of the customer to repay, that is, their creditworthiness. If they have problems in making timely

payments on their debts, this affects the value of the bank's assets and its own income inflows and ultimately

affects the net worth of the bank, the bank's capital ratio, and the shareholders' return on equity.

The bank's capacity to acquire reserves at low cost if

The customer wants to withdraw cash;

-The bank needs to pay debts to other banks through an interbank settlement following the customer's

spending(see below);

- The bank needs to settle tax payments made by the customer to the govern ment.

If these conditions are not satisfied the

bank gets into trouble: it can become

insolvent or illiquid. Insolvency means

that the bank's net worth falls to or

below zero; illiquidity

Bank A balance sheet showing loan

Figure 10.4

Liabilities

Assets

Cheque account of customer

+$200

means that it

cannot meet cash withdrawals or

clearing. Thus, even though banks can

create unlimited amounts of money

Loan to customer

+ $200

$200

Building

Net worth

$200

10お金と銀行

159

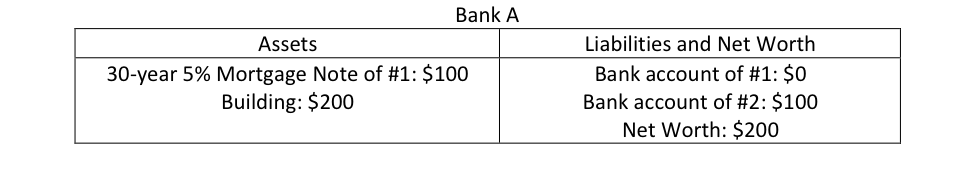

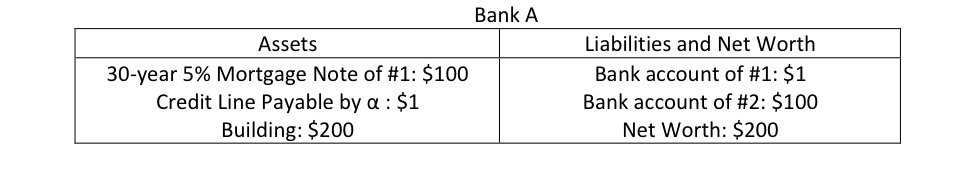

自動車の購入を示す銀行Aの貸借対照表

図10.5

預金、彼らはインセンティブを持っていません

そうなるかもしれないのでそうする

不採算。

顧客がいるとどうなりますか

資産の変更

負債の変動

顧客の小切手口座

- $ 200

銀行Bによる引当金

今自動車ディーラーに200ドルを支払う

銀行Bに銀行口座がありますか。の

銀行Aと銀行Bのバランスシート

+ 200ドル

それぞれ図10.5と10.6のように。

(私たちは今ちょうど扱っていることに注意してください

自動車の購入を示す銀行Bの貸借対照表

図10.6

資産および負債の変動に伴い

レベルではなく)

資産の変更

負債の変動

の形での銀行Aの負債

銀行Aの準備金に対する請求

+ 200ドル

カーディーラーの小切手口座

+ 200ドル

顧客の小切手口座は

その間に200ドルの減少

車を追いかけるが、取引は

銀行Aでの顧客のアカウントの残高の減少と自動車の残高の増加に限定されません。

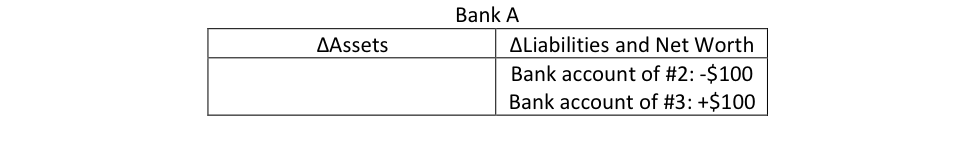

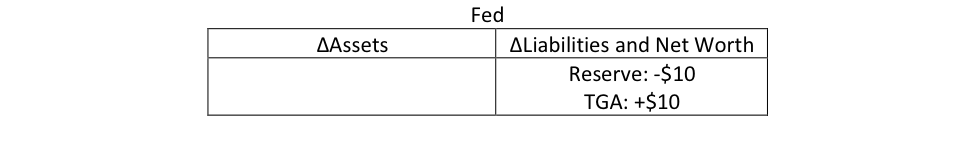

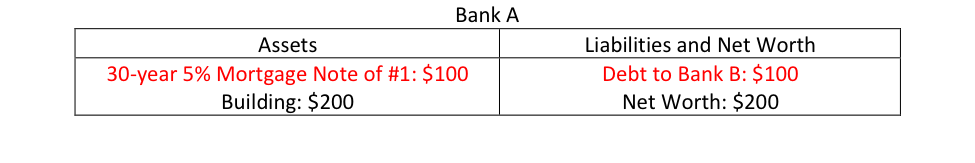

銀行Aは現在銀行Bの借金200ドルを負っており、この債務を決済するために準備金が必要ですが、準備金はありません。

それはどこで準備金を得ますか?

銀行は準備銀行口座を中央銀行に保管する必要があります。これらの準備金は中央銀行の負債です。

銀行や銀行の資産、および支払い(または決済)システムが機能することを保証するための機能

スムーズにこのシステムは、小切手のように銀行間で毎日行われる何百万ものトランザクションに関連しています。

市民や企業、その他の団体からの入札首尾一貫した引当金システムがなければ、銀行Aは容易に見つけることができます。

それ自体は、顧客の口座から引き出され、で提示された小切手に基づいて銀行Bの要求に資金を供給することはできません。

カーディーラーのそばの銀行B

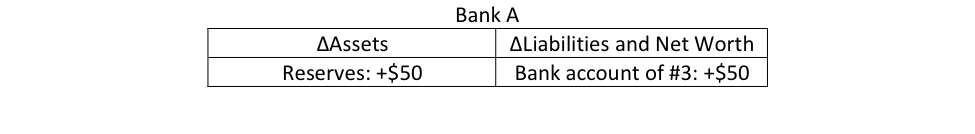

銀行Aは、最も費用のかからない資金源から準備金を受け取ります。それは資産を売るかもしれません、しかし、我々の例では、銀行

建物は1つだけなので、そのように準備金を得るのは非常に費用がかかります。銀行Aは、もしあれば債券を売却することができます。

他の銀行(国内外の銀行)または中央銀行から準備金を借りることができます。を取得する一般的な方法

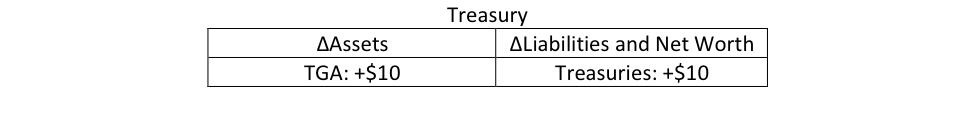

準備金は、準備金の独占供給者である中央銀行から借りることです。図10.7ドキュメント

これらの準備金の取得に関連する、銀行Aの貸借対照表への最新の変更。

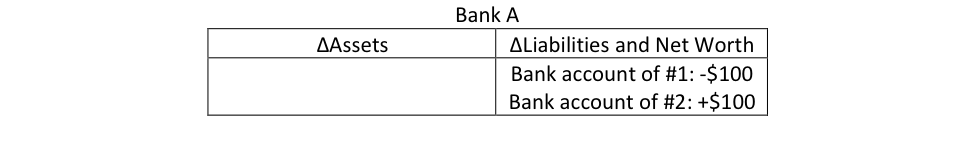

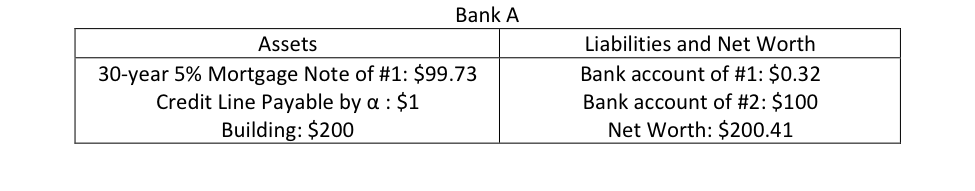

中央銀行の貸借対照表への変更

A銀行にはB銀行との債務を解決するための準備金がありますので、2つの銀行の残高の変化

シートを図10.9と図10.10に示します。

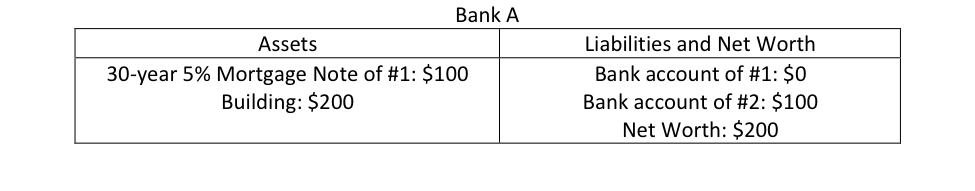

両銀行間の債務は解決された。銀行Aの最終貸借対照表は、図10.11のようになります。

顧客への融資で受け取る利子が、利子よりも大きい限り、銀行Aはお金を稼ぎます。

t準備金を中央銀行に支払う。

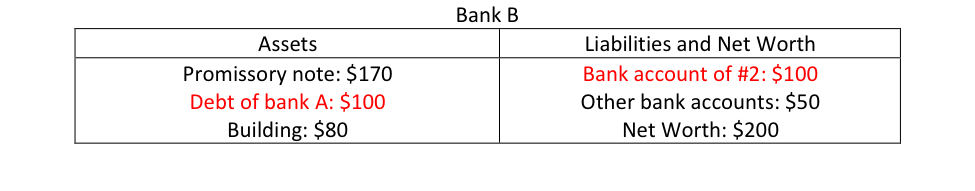

B銀行の貸借対照表は、

図10.12に示します。とする

B銀行は、

中央銀行からのローンを示す銀行A貸借対照表

図10.7

自動車販売店の口座を確認する

への車の販売により増加

負債の変動

資産の変更

顧客。

+ 200ドル

中央銀行への借金

+ 200ドル

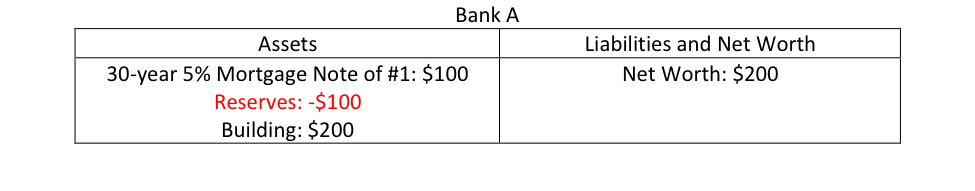

センターの最終貸借対照表

予約する

すべての取引が表示された後のトラル銀行

図10.13に示します。

これらの操作のどれも注意してください

現物現金の送金を伴う。それ

すべての簿記記入が行われたか

コンピュータネットワークを介してデジタル的に。

また、表示しただけであることに注意してください。

直接関連する資産と負債

ローンを示す中央銀行の貸借対照表

図10.8

負債の変動

資産の変更

+ 200ドル

予約する

+ 200ドル

銀行Aへの準備ローン

10Money and Banking

159

Bank A balance sheet showing purchase of car

Figure 10.5

deposits, they have no incentive to

do so because they may become

unprofitable.

What happens if the customer

Change in Assets

Change in Liabilities

Cheque account of the customer

-$200

Reserves due to Bank B

now pays $200 to a car dealer who

has a bank account at Bank B? The

balance sheets of Banks A and B look

+$200

like Figures 10.5 and 10.6, respectively.

(Note that we are now just dealing

Bank B balance sheet showing purchase of car

Figure 10.6

with the change in assets and liabilities

rather than their levels.)

Change in Assets

Change in Liabilities

Bank A's liabilities in the form of

Claim on Bank A reserves

+$200

Cheque account of car dealer

+$200

the customer's cheque account have

dropped by $200 through the pur-

chase of a car, but the transaction is

not confined to the reduced balances in the customer's acccount at Bank A and the increased balances of the car

dealer at Bank B. Bank A now owes Bank B $200 and needs reserves to settle this debt, but does not have reserves.

Where does it get the reserves?

The banks are required to keep reserve accounts at the central bank. These reserves are liabilities of the cen-

tral bank and assets of the banks, and function to ensure that the payments (or settlements) system functions

smoothly. That system relates to the millions of transactions that occur daily between banks as cheques are

tendered by citizens and firms and other bodies. Without a coherent system of reserves, Bank A could easily find

itself unable to fund Bank B's demands based on the cheque drawn on the customer's account and presented at

Bank B by the car dealer

Bank A will get the reserves from the source that is the least costly. It may sell assets, but in our example, Bank

A only has a building so it would be very costly to get reserves that way. Bank A could sell bonds if it had any, or

it could borrow reserves from other banks (domestic or foreign) or the central bank. A common way to get the

reserves is to borrow from the central bank, which is the monopoly supplier of reserves. Figure 10.7 documents

the latest change to Bank A's balance sheet, associated with obtaining these reserves, while Figure 10.8 shows the

changes to the central bank's balance sheet

Now that Bank A has the reserves it can settle its debt with Bank B. The changes to the two banks' balance

sheets are shown in Figures 10.9 and 10.10.

The debt between the two banks has been settled. The final balance sheet of Bank A looks like Figure 10.11

Bank A makes money as long as the interest it receives on the loan to the customer is higher than the interest

t pays to the central bank on the reserves.

The balance sheet of Bank B is

shown in Figure 10.12. We assume

that Bank B had reserves prior to the

Bank A balance sheet showing loan from central bank

Figure 10.7

cheque account of the car dealer being

increased by the sale of the car to the

Change in Liabilities

Change in Assets

customer.

+$200

Debt to central bank

+$200

The final balance sheet of the cen-

Reserve

tral bank after all transactions is shown

in Figure 10.13.

Note that none of these operations

involved any transfer of physical cash. It

was all bookkeeping entries conducted

digitally through computer networks.

Also, note that we have only shown

the assets and liabilities directly related

Central bank balance sheet showing loan

Figure 10.8

Change in Liabilities

Change in Assets

+$200

Reserve

+$200

Reserve loan to Bank A

160

通貨。お金と銀行

私たちの例に。もちろん、民間銀行

中央銀行には他にもたくさんある

資産および負債、ならびに自己資本

貸借対照表に

実際には、中央銀行はそうするでしょう

図10.9

借金の決済を示す銀行Aの貸借対照表

資産の変更

負債の変動

- $ 200

引当金

- $ 200

銀行Bによる引当金

同盟者は銀行に準備金を前払いしない

直接セキュリティで保護されていない形式で

前進;代わりにそれは担保を要求します

引き換えに(通常は国債)

とより少ないのための資金を提供します

担保の価値。 A銀行に

300ドルの債券、それは中央にそれを引き渡す

準備金と引き換えに銀行。中心 -

トラル銀行は、銀行に285ドルしか与えないかもしれません。

図10.10

借金の決済を示す銀行Bの貸借対照表

資産の変更

負債の変動

銀行Aに対する請求

- $ 200

引当金

+ 200ドル

割引率が5パーセントの場合割引率は、中央銀行が信用を制限しようとすることができる1つの方法です。

経済における創造。

図10.11

銀行Aの最終貸借対照表

負債

資産

$ 200

中央銀行への借金

$ 200

顧客への資金提供

建物

$ 200

純資産

$ 200

銀行Bの最終貸借対照表

図10.12

負債

資産

$ 200

カーディーラーの小切手口座

引当金

$ 200

中央銀行の最終貸借対照表

図10.13

資産

負債

銀行Aへの準備ローン

$ 200

引当金

$ 200

160

CURRENCY. MONEY AND BANKING

to our example. Of course, private bank

and the central bank have many other

assets and liabilities, as well as net worth

on their balance sheets

In practice, the central bank will isu

Figure 10.9

Bank A balance sheet showing settlement of debt

Change in Assets

Change in Liabilities

-$200

Reserves

-$200

Reserves due to Bank B

ally not advance reserves to the bank

directly in the form of an unsecured

advance; instead it will ask for collateral

(usually a treasury security) in exchange

and will provide funds for less than the

value of the collateral. So, if Bank A has a

$300 bond, it surrenders it to the central

bank in exchange for reserves. The cen-

tral bank might only give the bank $285

Figure 10.10

Bank B balance sheet showing settlement of debt

Change in Assets

Change in Liabilities

Claim on Bank A

-$200

Reserves

+$200

if the discount rate is five per cent. The discount rate is one way in which the central bank can try to limit credit

creation in the economy.

Figure 10.11

Bank A final balance sheet

Liabilities

Assets

$200

Debt to central bank

$200

Funds advanced to customer

Building

$200

Net worth

$200

Bank B final balance sheet

Figure 10.12

Liabilities

Assets

$200

Cheque account of car dealer

Reserves

$200

Central bank final balance sheet

Figure 10.13

Assets

Liabilities

Reserve loan to Bank A

$200

Reserves

$200

10お金と銀行

161

他の銀行から、あるいは中央銀行による準備金の創出を通じて。我々はより詳細に説明します、

そしてなぜ、中央銀行は第20章の準備金の需要に対応するのか。

参考文献

Brunner、K.(1968)「貨幣と金融政策の役割」、セントルイス連邦準備銀行、50、8-24。

ムーア、B。 (1988)水平主義者と垂直主義者:ケンブリッジのクレジットマネーのマクロ経済学:ケンブリッジ大学

押す。

文末脚注

1.正統派のエコノミストは、名目金利は実質金利に期待インフレを加えたものに等しくなければならないと提案している。

実質金利は、市場で決定された実質収益であり、これは

資金のための投資需要と資金。したがって、それは実質均衡金利です。しかし、契約は

名目で、つまり名目金利で書かれている場合、名目金利は報酬を含まなければなりません

expの

(Box 10.2を参照)。多くの市場参加者は、これが債券市場に当てはまると考えています。名目上の強い信念があります

購買力を維持するために、利回りは市場によって調整されます。

dインフレ率。インフレ期待が上がるにつれてこの実質金利に加わることはフィッシャー効果と呼ばれます

その他の資料については、コンパニオンWebサイト(www.macm illanihe.com/mitchell-macro)を参照してください。

作者のビデオ、講師用マニュアル、うまくいった例、チュートリアルの質問、その他

参考文献、本文中のさまざまなグラフの作成に使用されるデータセットなど。

10 Money and Banking

161

them from other banks or through creation of reserves by the central bank. We will explain in more detail how,

and why, central banks accommodate the demand for reserves in Chapter 20.

References

Brunner, K. (1968)" The Role of Money and Monetary Policy", Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review, 50, 8-24.

Moore,B. (1988) Horizontalists and Verticalists: The Macroeconomics of Credit Money, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Endnote

1.Orthodox economists propose that the nominal interest rate must equal a real interest rate plus expected inflation.

The real interest rate is supposed to be the market-determined real return that will equate the saving supply of

funds with the investment demand for funds. It is thus a real equilibrium interest rate. However, as contracts are

written in nominal terms, that is, in terms of nominal interest rates, the nominal rate must include compensation

for the exp

(see Box 10.2). Many market participants believe this applies to bond markets. There is a strong belief that nominal

yields are adjusted by markets to preserve purchasing power.

d inflation rate. This addition to the real rate as inflation expectations rise is called the Fisher effect

Visit the companion website at www.macm illanihe.com/mitchell-macro for additional resources

including author videos, an instructor's manual, worked examples, tutorial questions, additional

references, the data sets used in constructing various graphs in the text, and more.