Macro modelling MMT

“The accounting identities equating aggregate expenditures to production and of both to incomes at market prices are inescapable, no matter which variety of Keynesian or classical economics you espouse. I tell students that respect for identities is the first piece of wisdom that distinguishes economists from others who expiate on economics. The second? … Identities say nothing about causation.” James Tobin, leftist Keynesian 1997

“Money is ultimately a creation of government—but that doesn’t mean only government deficits determine the level of demand at any one time. The actions and beliefs of the private sector matter as well. And that in turn means you can have budget surpluses and excess demand at the same time, just as you can have budget deficits and deficient demand.” Jonathan Portes (orthodox Keynesian).

The increasingly abstruse debate among economists (mainstream, heterodox and leftist) continues on the validity of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its relevance for economic policy. The debate among leftists went up another gear with the publication of leftist Doug Henwood’s fierce critique of MMT in Jacobin

here. Leading MMTer Randall Wray angrily responded to Henwood’s attempted demolition

here. And then from the heart of MMT land, Pavlina Tcherneva, program director and associate professor of economics at Bard College and a research associate at the Levy Economics Institute replied to Henwood in

Jacobin.

In the mainstream,

Paul Krugman had a go, with a

response from Stephanie Kelton. Kelton is a professor of public policy and economics at Stony Brook University, Long Island New York. She was the Democrats’ chief economist on the staff of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee and an economic adviser to the 2016 presidential campaign of Senator Bernie Sanders.

Although this debate is getting very arcane and even nasty, it is not irrelevant because many leftists in the labour movement have been attracted by MMT as theoretical support for opposing ‘austerity’ and for justifying significant government spending to obtain full employment and incomes. In particular, the radical wing of the Democrat party in the US has

used MMT to support their call for a Green New Deal – arguing that more government spending on the environment, climate change and health can easily be financed by the issuance of dollars, rather than by more taxes or more government bonds that would raise public debt.

I won’t pitch into the MMT debate as above as

I have already spent some ink in three posts trying to critique the theory and policy of MMT from a Marxist viewpoint, with the aim of working out whether MMT offers a way forward to meeting ‘the needs of the many’ (labour) over the few (capital). And for me, that is the ultimate purpose of such a debate.

All I would add on the current debate among Keynesian, Post-Keynesians and MMTers is that MMTers argue with orthodox Keynesians over whether government spending can create the money to finance it; or taxation and borrowing is needed to create the money to fund government spending. But as post-Keynesian

Thomas Palley puts it: “government spending and taxation occur simultaneously so creation of money via money financed deficits and destruction of money via taxation also occur simultaneously. It is a pointless exercise to try and determine which comes first.” Marxist analysis would agree.

Instead, in this post I want to look at MMT’s macro model. In the twitter debate that is viral (at least among economists and activists!), critics of MMT have sometimes argued that MMT is just a series of vague assertions without any rigorous model. This riled Kelton. She immediately posted

a paper written in 2011 by Scott Fullwiler of Warburg College, another MMT leader (who also recently commented on one of my blog posts). In this paper, Scott outlined the MMT macro model in some detail.

Basically, he starts off with a Keynes/Kalecki post-Keynesian macro model of aggregate demand. This model is simply an identity. There are two ways of looking at an economy, by total income or by total spending and they must equal each other.

Thus National Income (NI) = National Expenditure (NE).

(NI) Profits + Wages = (NE) Investment + Consumption. Now there are two sorts of income and two sorts of spending.

If we assume that all Wages are spent then and all Profits are saved, we can delete Wages and Consumption from the identity. So

Profits = Investment

In the MMT version from Scott, he puts the same macro identity differently, with Investment on the left side of the equality. Thus.

Investment = Profits

Why? Because, as we shall see, all post-Keynesian theory argues that it is Investment that leads Profits, not vice versa.

But Scott re-expands the parts on the right-hand side to look at flows, so that wages that are saved are added back with profits to get Private Saving (so assuming some household saving); and he also adds in Government saving (taxation less spending) and Foreign Saving (net imports or current account deficit).

Thus Profits as a separate category disappears into Private Savings and we get:

Investment = Private Saving + (Taxation – Government Spending) + (Imports – Exports)

But then Scott also dispenses with the separate category Investment and converts it into Private Saving less Investment or the Private Sector Surplus. So now we have Private Sector Savings (Wages saved plus Profits less Investment). So Scott continues:

Private Sector Surplus = Government Deficit + Current Account Balance

Or

Private Sector Surplus – Current Account Balance = Government Deficit

This is the key MMT identity. It argues that if the Government deficit rises, then assuming the Current Account balance does not change, the Private Sector Surplus (Wages saved +Profits less Investment) rises. The MMT conclusion (assertion) is that increasing the Government deficit will increase the Private Sector Surplus . And if we exclude Wages saved (the MMT identity does not) and the Current Account balance, then we have:

Net Profits (ie Profits after Investment) = Government deficit

And we can conclude that Government deficits determine Net Profits ie Profits less Investment.

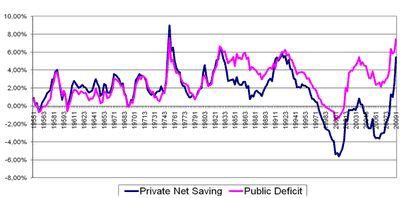

In the paper Scott then presents a time series graph comparing US Private Net Saving (remember this includes Household net saving) with Government deficits and concludes that “It shows how closely the private sector surplus and the government sector deficit have moved historically, which isn’t surprising given they are nearly the opposing sides of an accounting identity.”

But then Scott says: “What we notice (from these graphs) is that the current rise in the government’s deficit is creating net saving for the private sector.” But is that how to view the causal direction of these macro identities? The post-Keynesians reckon that the causal connection is that Investment creates Profits or in the MMT version Government deficits create net profits (private saving). But in my view, the causal direction of this identity is in reality the opposite, namely that Marxian theory says that Profits create Investment, because Profits come from the exploitation of labour power.

Let us go back to the basic Kalecki identity, Profits = Investment, with Investment back on the right hand side. Investment (which disappeared in Scott Fulwiller’s model) can be broken down to Capitalist investment and Government investment.

Profits = Capitalist investment + Government investment

Under the Kalecki causation, increasing government investment (by deficits, if you want) will raise Profits (and for that matter, wages too through more employment and wage rates – the post-Keynesian identities just refer to Private Saving and (importantly) do not break that out into Wages saved and Profits).

Thus Profits + Wages saved = Private investment + Government investment

But what if the Kalecki causation is back to front? What if Profits lead Investment, not vice versa. Then the identity is:

Profits (because Wages are spent) = Investment (comprising Capitalist investment and Government investment). We can expand this to cover external flows so that:

Domestic Profits + Foreign Income = Capitalist investment + Government Investment + Foreign Inward Investment

Now assume both Domestic Profits and Foreign Income are fixed. What will happen if Government Investment rises? Private Investment will fall unless foreign inward investment rockets.

How can government investment/spending be increased without Private (capitalist?) investment falling (being crowded out)? By running budget deficits, say the post-Keynesians (and MMT). Borrowing could be done by issuing government bonds (orthodox Keynesian) or by ‘printing money’ ie increasing cash reserves in banks (MMT). Issuing bonds may reduce Private Investment to boost Government investment, but the credit created would stimulate overall Investment. Printing Money (MMT) would raise Investment without reducing Private Investment (magic!). MMT/Keynesians will say if Government Investment is not funded by taxes on Domestic Profits but by borrowing with bonds or printing money, then it will not affect profits.

Marxists would say that this is ‘fictitious’ investment that must deliver higher profit at some point.

All this is because identities do not reveal causation and it is causation that matters. For the Keynesians, it is the right hand side of the equation (Investment) that causes the left hand side (Profits); namely, that it is capitalist investment and consumption that creates profit. For MMTers, it is a variant of the same, but netted: Net government investment/spending (deficits after taxes) causes Net Private Savings (Profits and Saved wages after investment).

But in the real world of capitalist production, this is back to front. Profits lead Investment, not vice versa; and Net Private Savings enable Government deficits not vice versa. The graphs offered by Scott in his paper of the time series of deficits and net private surpluses can be interpreted with just that causality. What I read from the first graph is not “that the current rise in the government’s deficit is creating net saving for the private sector” (Fullwiler), but the opposite: higher net savings (profits after investment) will produce a higher government deficit or lower surplus. In other words, when capitalists hoard/save and won’t invest, and that is particularly the case in recessions, then government deficits rise (through lower tax revenues and higher unemployment benefits). And Scott’s graphs show that the US government deficits reach peaks in all the post-war US recessions and are at their lowest in boom times.

Indeed, if I do the correlations between the government balance and net private savings, there is indeed a very small inverse relation of 0.07; in other words, a larger government deficit is correlated (weakly) with a net private savings surplus. But if I do the correlation between the government balance and GDP growth, there is a small positive correlation. In other words, more government surplus/less deficit aligns with more GDP growth, the opposite of the Keynes/Kalecki causation, which suggests that it is growth that leads government balances, not vice versa (see the Portes quote above).

Any causation is also modified by the external account. Scott’s second graph including the current account shows that a persistent current account deficit (net foreign inflows) from the 1980s helped to fund US government deficits, even though the private sector surplus disappeared in the 2000s. So the main MMT causation argument is further muddied by foreign income.

We can only really better understand the causal connections if we have Investment isolated and Profits isolated. You see, contrary to the Keynesian/post-Keynesian/MMT view, the Marxist view is that “effective demand” (including government deficits) cannot precede production. There is always demand in society for human needs. But it can only be satisfied when human beings do work to produce things and services out of nature. Production precedes demand in that sense and labour time determines the value of that production. Profits are created by the exploitation of labour and then those profits are either invested or consumed by capitalists. Thus, demand is only ‘effective’ because of the income that has been created, not vice versa.

Because the Keynesians/post-Keynesians have no theory of value, they do not recognise this and read their own identity the wrong way round. From a Marxist view, profits are the causal variable. So if profits fall, then either investment, or capitalist hoarding or the government deficit must fall, or all three.

What is the evidence that profits lead investment and government deficits and not the other way round, as the Keynesians argue? This blog has provided overwhelming

empirical support to the Marxist causal direction. See my paper

here which compiles all the compelling empirical research (including my own) that supports the Marxist view that, in a capitalist economy, profits lead investment, which in turn drives GDP growth and employment, while government deficits have little influence.

If the Keynes/Kalecki causation direction is right, then all that we need to do to keep a capitalist economy going is to have more government budget deficits. If the MMTers are right, all we need to achieve permanent full employment is permanent government deficits (subject to some possible inflation constraint). What the orthodox Keynesians and the MMTers disagree about is whether these deficits (of government spending over taxes) can and should be financed by issuing government bonds for banks to buy or by the central bank printing money.

The more important question, however, is what drives a capitalist economy. It is the profitability of capitalist investment that drives growth and employment, not the size of a government deficit. The Keynes/Kalecki/MMT macro models hide behind identities and turn them into causes. But identities “say nothing about causation” (Tobin). It’s profits, not government spending, that call the tune.